The key assumptions behind the “Moneyball” 30 Year Shipbuilding Plan in support of the “Pivot to the Pacific” are unraveling. The USN force structure is proving itself to be fundamentally disconnected from the foreign policy that it is supposed to be supporting and is therefore standing into a strategic paradox. The following article is a sequel to a posting in May 2013 https://cimsec.org/the-greenert-gambit/

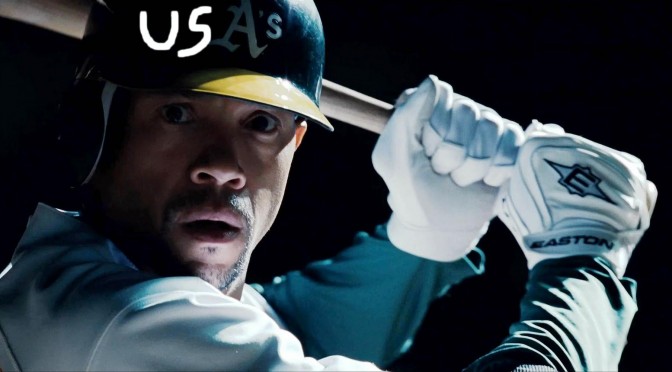

Moneyball is no different from any other strategic planning framework: the goal is to set your team up to win a campaign. To effectively play Moneyball, you have to have confidence that your sabermetrics are accurate—have you properly distilled down the key elements to win your campaign? Can you acquire them at an affordable cost? Can you maintain them for as long as needed?

In 2013, CNO Greenert took a big risk with his 30 year shipbuilding plan. Tasked with supporting the Pivot to the Pacific in a fiscally constrained environment, Greenert boldly chose to complement legacy combatant aircraft carriers, cruisers and destroyers with new focus on “Moneyball” assets such as Littoral Combat Ships, Joint High Speed Vessels, Afloat Forward Staging Bases and Maritime Pre-Positioning Ships in order to increase his sabermetric elements of presence, C2, and lift. When tasked to act in ensuring regional stability, the US Navy historically deploys armadas of capital warships to stare down any potential rogues. This Pacific stability campaign, however, was to be different, and as such success could be predicated with a different kind of naval force—a cheaper, lighter, more flexible force that would empower the administration’s foreign policy mission of

“…strengthening alliances; deepening partnerships with emerging powers; building a stable, productive, and constructive relationship with China; empowering regional institutions; and helping to build a regional economic architecture that can sustain shared prosperity.” (NSA Tom Donilon, 2013)

One year and an LCS forward deployment to Singapore / HA/DR mission to the Philippines later, the report card is troubling. Our alliances in the Pacific are no stronger with successive Air Defense Identification Zones popping up all over the Pacific; our partnerships with emerging powers such as India (Exercise MALABAR cancellation), Indonesia (Australia naval crisis), and Malaysia (opening its waters to Chinese in shore patrols) are threatened by their fear of incurring Chinese wrath. Meanwhile, the member states of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) are being picked off one at a time by China in a series of coercive bi-lateral negotiations aimed at expanding both the Chinese economic exclusion zone (EEZ) and territorial waters outside of the less pliable ASEAN multilateral framework. In all of these existential threats to the stated purpose of the Pivot to the Pacific, the US State Department has been conspicuously missing in action.

At the 2014 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Secretary of State John Kerry refuted assertions that US foreign policy appeared to be hibernating by stating,

“This misperception appears to be based on the simplistic assumption that our only tool of influence is our military, and that if we don’t have a huge troop presence somewhere or we aren’t brandishing an immediate threat of force, we are somehow absent from the arena.”

The results of recent high profile diplomatic efforts absent aggressive US military action have not been promising. As of 3/12/2014, Syria has delivered only 5% of its chemical weapons to international inspectors for destruction in clear violation of the multilateral framework; the Director of National Intelligence has announced a North Korean expansion of its nuclear weapons program; and Iran is flip-flopping on their commitment to permanently disavow their nuclear weapons program; Russia has invaded Ukraine and is controlling all of Crimea.

The State Department’s apparent lack of coordination with the Department of Defense in the implementation of the Pivot to the Pacific and coercion of rogue states is threatening the US Navy force structure with a strategic paradox: the sabermetric underpinnings of the Moneyball fleet did not forecast a diplomatic retreat in the pacific and a military retreat against rogue states. As a result, the AFSBs, MLPs, JHSVs, LCS’s of the Moneyball fleet are in no position to provide a credible counter to Chinese attempts at forcibly expanding their regional hegemony over US partners / allies, and are in danger of being stretched to the breaking point by having to maintain in extremis and contingency forces across multiple AORs (that could otherwise be stabilized through a concerted, coordinated (total government) application of military force and foreign policy).

In 2013, I argued that, “…key to achieving [the Pivot’s] strategic aims is regional stability—a stability that can only be maintained with the confidence of regional power brokers that the status quo is acceptable and not threatened.” That dream is crushed—the status quo is under assault. The CNO’s options are to rally for State Department to get back into the game before it is too late, or to abandon Moneyball altogether and start laying the groundwork for a Navy that can achieve the goals of the Pivot to the Pacific all on its own.

Nicolas di Leonardo is a member of the Expeditionary Warfare Division on the staff of the US Chief of Naval Operations, as well as a graduate student of the US Naval War College. The views presented here are his own and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the United States Navy or the US Naval War College.

Great points, but, I don’t think the Navy needs to go it alone in the Pacific, even if the other instruments of US national power seem to be currently MIA. I offer that the Coast Guard is an ideal partner – particularly in the Pacific – to help the Navy with “…strengthening alliances; deepening partnerships with emerging powers; building a stable, productive, and constructive relationship with China; empowering regional institutions; and helping to build a regional economic architecture that can sustain shared prosperity.”

Consider just one piece of the puzzle: the Coast Guard has extensive fisheries expertise, presence, partnerships, and respect in the Pacific. Coast Guard assets can access small and shallow Pacific Island atolls with relative ease, and Coast Guard personnel are intimately familiar with asymmetric and irregular maritime conflict. The Coast Guard conducts ongoing shiprider exchanges with many of the Pacific Island and Pacific Rim nations – including with China. While fish may seem insignificant, it is through a “fisheries EEZ” that China seeks to enforce its maritime claims in the South China Sea…following a multi-year economic “outreach” that permitted de facto resource control of many other sections of the remote Pacific.

To get the best return on investment for a Pacific pivot, it might well be worth looking at an expanded and more integrated role for the Navy’s “kid sister” service.

The Coast Guard is one of the most over utilized and under resourced services in the entire US Government. If I were king, I would significantly expand both the manning and budget lines of the USCG. I only wonder if we could find enough of the unique men and women that currently make up the USCG to do all the missions that I would sign the USCG up for!

Hell, I’d fold up Annapolis and turn over its duties to the USCGA.

From your mouth to Congress’s votes…

Considering we have quite the waiting list, and are currently downsizing…I think we could handle a certain degree of expansion without trouble. As long as our resources expanded enough for all those extra missions you’re envisioning!!