By Adam Taylor

Recent remarks by Admiral Phil Davidson, Commander of the Indo-Pacific Command (INDO-PACOM), highlights one of the most difficult challenges confronting US naval forces in the Asia-Pacific—America’s conventional deterrence posture in the region. He noted “the greatest danger for the United States in this competition [with China] is the erosion of conventional deterrence. Absent a convincing deterrent, the People’s Republic of China will be emboldened to take action to undermine the rules-based international order.” This statement deserves further consideration among naval observers given its assumptions about the nature of conventional deterrence, possible ramifications on the composition and disposition of US forces in the region, and implications for the Navy’s future force design. An assessment of the Navy’s recent “Battle Force 2045” vision against the utility of its traditional contributions to conventional deterrence and the implications associated with differing US and Chinese ideas about deterrence unfortunately demonstrates that the service’s future force design remains ill-equipped to address the deterrence deficit confronting the US.

Deterrence represents one form of coercive diplomacy, which the DoD defines as the “prevention of action by the existence of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction and/or belief that the cost of action outweighs the perceived benefits.” Compellence constitutes a different form of coercive diplomacy, representing the “use of threatened force, including the limited use of actual force to back up the threat, to induce an adversary to behave differently than it otherwise would.” States can employ these coercive approaches through various instruments of power in their pursuit of national interests.

Strategies of deterrence and compellence differ in their relationships to the prevailing status quo : Deterrence seeks to preserve the status quo, while compellent policies seek to alter it. Other important differences between both strategies include the passage of time and initiator of action. Deterrence strategies passively wait for the object of the deterrent strategy to initiate action, while compellence requires continuous and active efforts by the coercing state.

As a status quo great power, America’s deterrence paradigm informs the Navy’s contributions to the nation’s conventional deterrence posture. Three of its nine functional contributions to the joint force directly contribute to conventional deterrence posture:

- Conduct offensive and defensive operations associated with the maritime domain including achieving and maintaining sea control, to include subsurface, surface, land, air, space, and cyberspace;

- Provide power projection through sea-based global strike, to include nuclear and conventional capabilities; interdiction and interception capabilities; maritime and/or littoral fires to include naval surface fires; and close air support for ground forces;

- Establish, maintain, and defend sea bases in support of naval, amphibious, land, air, or other joint operations as directed.

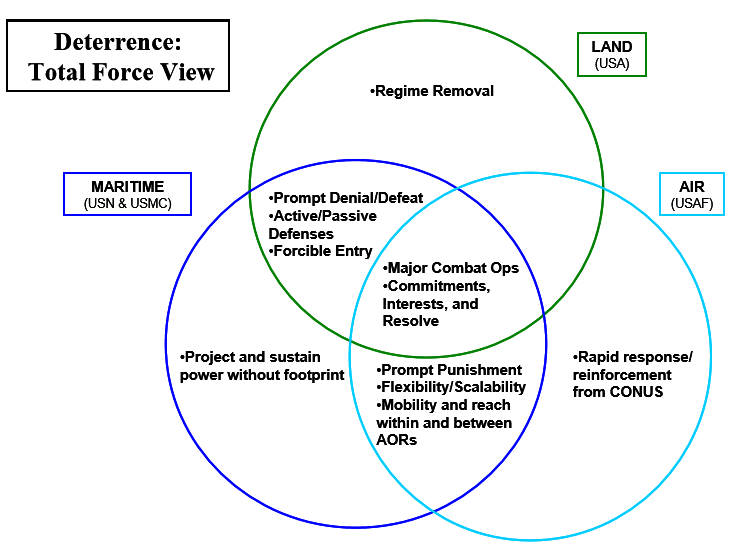

The chart below from a Center for Naval Analyses report illustrates how the Navy’s deterrent contributions fit into the broader joint force deterrent posture.

The Navy’s ability to “loiter” and remain minimally intrusive highlights why the service is best suited to provide mobile, prompt, and flexible conventional deterrent forces that can sustainably project power without a footprint. The resources needed to deploy and sustain land forces may effectively signal a state’s deterrent commitment, but require time to generate and are relatively less mobile within a theater of operations. Conversely, air power can provide prompt response and minimally intrusive capabilities, but is limited by platforms’ relatively short time on station compared to naval assets. The Navy mitigates these issues through a variety of means, as noted in the same report:

“When maritime power is used, countries can keep from appearing to have an overly close relationship with the United States that might spark new, or enflame ongoing, socio-cultural tensions and violence, while at the same time enjoying the security benefits of US forces in the area vis-à-vis regional adversaries. In fact, if there is a continuing trend in which countries want completely new US security commitments and/or strengthened assurances of existing guarantees, but at the same time do not want to host US forces on their soil, maritime power may increasingly become the primary military instrument used to simultaneously assure allies and deter adversaries.”

Naval operations can simultaneously address the need for commitment without the costs associated with permanent military installations because they do not need basing or overflight rights like land or air forces and can maintain either an overt or “over the horizon” presence. These qualities led Oliver Cromwell to famously declare that a “man-o-war is the best ambassador.” They also demonstrate how naval assets can credibly communicate the commitment needed to deter without incurring political costs or unnecessarily antagonizing potential belligerents.

These qualities ensure the Navy remains a crucial element of America’s deterrence posture in the Asia-Pacific given the contestable nature of conventional deterrence. Prompt denial mitigates opportunistic aggression by limiting the likelihood of quick and low-cost victory. The Navy’s combination of air, sea, and land assets ensures the service has the organic ability to counter aggression. Similarly, the service’s ability to loiter in zones of contention for extended periods of time means the Navy can demonstrate the political resolve and commitment needed to convince potential belligerents to abandon hostile courses of action – but only if those potential belligerents find the deployed forces to be credible.

China, however, pursues a conventional deterrence strategy at odds with America’s deterrence paradigm. The PRC defines deterrence as “the display of military power or the threat of use of military power in order to compel an opponent to submit.” This definition encompasses both dissuasion and coercion in a single concept. Chinese military writing emphasizes that deterrence has two important functions: “one is to dissuade the opponent from doing something through deterrence, the other is to persuade the opponent what ought to be done through deterrence, and both demand the opponent submit to the deterrer’s volition.” Beijing’s definition of deterrence also suggests it views deterrence as a way to achieve a desired political outcome. Deterrence represents a means to a specific end. American discussions tend to characterize deterrence as a goal. INDOPACOM’s mission to field a “combat credible deterrence strategy…” highlights this distinction.

American versus Chinese Views of Deterrence

| Strategy | Definition | Temporal Constraint | Object of Force | Characteristics |

| American Deterrence | Dissuade an opponent from taking an unwelcome action by threatening the use of force. | Occurs during peace time. | Passively influence enemy’s intentions to prevent future challenge to status quo. | Status quo posturing can be viewed as first strike preparations. |

| Chinese Deterrence | Dissuade or coerce an opponent through the display of military power or threatening the use of force in order to compel an opponent to submit. | Occurs during peace and war time. | Requires object of deterrence to preference Chinese political interests at object’s expense. | Multi-domain; preemptive; contests disputed sovereignty claims; crisis amenable. |

The PLA pursues deterrence through a strategy of “forward defense.” This strategy calls for China “pushing the first line away from China’s borders and coasts to ensure that combat occurs beyond China’s homeland territory, not on or within it…China’s borders and coasts are now viewed as interior lines in a conflict, not exterior ones.” China incorporates a variety of conventional, space, information capabilities, economic, and diplomatic means into its deterrence policy tool bag. All of these measures combine to aide Beijing’s deterrence policy which aims to compel an aggressor to abandon offensive intentions or cause a defender to conclude the cost of resistance remains too high. The offensive nature of Chinese deterrence means Beijing would consider preemptive action during periods of tension should the PRC conclude an aggressor has decided to violate China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Beijing’s use of force in its deterrence strategy also highlights the value it places on crisis and tension. While American policy makers might consider a crisis that challenges the status quo a possible point of deterrence failure, Chinese leadership views crisis as an avenue to achieve favorable political outcomes. A crisis or increase in tension that might not normally exist under the status quo allows the PRC to probe an adversary’s intentions, foment friction among allies, weaken an opponent’s resolve, or decrease the domestic political support for an adversary’s policies.

The divergence in deterrence theory and practice between both nations has important implications for the Navy’s future force design. China’s impressive anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities combined with a deterrence strategy that favors crisis escalation and encroachment on other nations’ sovereignty challenges the Navy’s ability to effectively deter. The Navy can no longer assume that its ships’ ability to loiter in zones of contention will deter an increasingly capable Chinese military from taking unwanted action. Navy leadership also must reconsider if the fleet’s current composition and posture adequately conveys America’s daily commitment to its allies or provides a realistic deterrent against belligerent Chinese behavior short of war. Aircraft carriers, high-tech destroyers, and attack submarines do an excellent job demonstrating the Navy’s capabilities should conventional war occur, but do not necessarily represent the best choice when dealing with the daily and persistent malign behavior that China employs. These platforms cost a lot to operate and maintain which means the Navy cannot endlessly keep them at sea in contested areas. Furthermore, it likely strains Chinese credulity to believe that the US would employ its qualitatively superior platforms to respond to every escalatory action Beijing engages in against American partners. Washington would look overreactive and all too willing to consistently let its ships and sailors operate in a costly A2/AD environment.

All of these issues raise important questions about the Navy’s ability to deter Chinese aggression, manage escalation, and credibly prevail in a great power conflict. The future fleet must possess the ability to decisively win a conventional conflict while also maintaining the capability needed to deter aggression short of war. Beijing’s deterrence paradigm requires a navy that can compete with China across the entire spectrum of operations. Unfortunately, the Navy’s recently released “Battle Force 2045” concept falls short of these requirements with its over investment in surface combatants, under investment in uncrewed ships, and unrealistic assumptions about defense budgets. A more thorough review of the Navy’s ability to respond to conventional aggression against Taiwan will demonstrate the service’s current shortcomings and the way ahead for a more sustainable and effective force design.

Adam Taylor recently separated from the Marine Corps where he served four years as an air support control officer and is now in the Individual Ready Reserve. He currently works as a fellow in Congress and received his M.A. in international relations from American University’s School of International Service. The opinions expressed here are his own and do not reflect any institutional position of the Marine Corps, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or Member of Congress.

Featured Image: INDIAN OCEAN (March 20, 2021) Electronics Technician 2nd Class Ryan Walsh, from Monroe, N.Y., watches the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) from the flight deck of the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Russell (DDG 59) March 20, 2021. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Wade Costin)