The following article was originally featured by the National Maritime Foundation and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Gurpreet S. Khurana

On 12 July 2016, the Tribunal constituted at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) at The Hague under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, 1982 (UNCLOS) issued its decision in the arbitration instituted by the Philippines against China. It relates to the various legal issues in the South China Sea (SCS) inter alia pertaining to China’s historic rights and ‘nine-dash line,’ and the status of features and lawfulness of Chinese actions.1

Within hours of the release of PCA Tribunal’s decision, India released a government press release, stating that

“India supports freedom of navigation and over-flight, and unimpeded commerce, based on the principles of international law, as reflected notably in the UNCLOS. India believes that States should resolve disputes through peaceful means without threat or use of force and exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that could complicate or escalate disputes affecting peace and stability…”2

However, Beijing has stated that China would not accept the Tribunal’s verdict.3 Furthermore, tensions have rekindled in the SCS with reports indicating that China intends “closing off a part of SCS for military exercises.”4 The issue of Freedom of Navigation (FON) is of immense relevance not merely for the SCS littorals, but for all countries that have a stake in peace and tranquillity in the SCS; and yet bears a significant potential to flare-up into a maritime conflict.

This issue brief aims to examine China’s approach to FON in context of international law, including the verdict of the PCA Tribunal. In this writing, the term ‘FON’ refers to the broader concept of ‘navigational freedoms,’ including the freedom of over-flight. Furthermore, this brief attempts to identify the de jure ramifications – even if not de facto, considering China’s rejection of the verdict – of the PCA Tribunal’s decision on China with regard to FON in the area.

FON is a fundamental tenet of customary international law that was propounded in 1609 by the Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius, who called it Mare Liberum (Freedom of the Seas). The legal tenet is codified in the UNCLOS, a process that involved over two decades of intense labor of international maritime lawmakers at three brainstorming Conferences. The Third Conference itself (UNCLOS III) spanned nine years, which led to the signing of Convention in 1982 and its subsequent entry into force in 1994. The Peoples’ Republic of China was among the first signatories to the Convention on 10 December 1982 (along with India), and ratified it on 07 June 1996. The key question is whether China – despite the foregoing – is impeding freedom of navigation in the SCS? For a comprehensive answer, the issue would need to be examined separately for the three legal regimes/ areas wherein international law applies differently: China’s Territorial Sea, its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and the other areas within the ‘nine-dash line.’

Territorial Seas

In a State’s 12-nautical mile (NM) Territorial Sea, the right of ‘Innocent Passage’ provided for in UNCLOS Article 17 applies to both commercial and military vessels. As regards commercial shipping, there is no evidence whatsoever of China denying this right to such ships flying the flag of any nationality. Notably, China is a manufacturing-based and export-led economy, which imports nearly 80 percent of its oil and natural gas via the sea. Therefore, China has tremendous stakes in unimpeded maritime commerce, and does not stand to gain by deliberately impeding the FON of merchant ships.

For foreign warships, however, the ‘yardstick’ of ‘Innocent Passage’ differs. During the UNCLOS negotiations, most developing countries wanted restrictions on foreign warships crossing their Territorial Seas. Many of these States proposed that foreign warships must obtain ‘authorization’ for this from the coastal State. Eventually, however, the proposed amendment was not incorporated in UNCLOS; nonetheless, the States were permitted to take measures to safeguard their security interests. Consequently, and in accordance with UNCLOS Article 3105, like many other States, China made a declaration in June 1996 while ratifying UNCLOS, seeking ‘prior permission’ for all foreign warships intending to exercise the right of Innocent Passage across its Territorial Seas.6 The declaration was based upon Article 6 of China’s national law of 1992.7 It is pertinent to state that about 40 other States – including many developed countries in Europe – made similar declarations seeking ‘prior permission’ for Innocent Passage. (Notably, India seeks only ‘prior notification’. However, the United States does not recognize the right of either ‘prior permission’ or ‘prior notification’).8

It may be recalled that during the Cold War, in 1983, the Soviet Union promulgated rules for warship navigation in its Territorial Seas, which permitted Innocent Passage only in limited areas of Soviet Territorial Seas in the Baltic Sea, the Sea of Okhotsk, and Sea of Japan. This led to a vigorous protest from the United States. Later in 1986 and 1988, the United States Navy conducted Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in the Soviet Territorial Sea in the Black Sea.9 In contrast, therefore, China’s stand on navigation of foreign warships through Territorial Seas of ‘undisputed’ Chinese territory is clearly legitimate.

However, the passage of foreign warships within 12-NM of the disputed SCS islands/features – which are occupied and claimed by China – has been highly contentious. Since the United States seeks to prevent any norm-building in favor of China’s territorial claims, it has been undertaking FON operations (FONOPS) in the 12-NM zone of these islands. Notably, since the launch of the U..S “Freedom of Navigation Program” in 1979, the United States has conducted such operations on numerous occasions all around the globe; sometimes even against its closest allies.

From the perspective of China – that is in de facto control of the islands/features – its objection to the U.S. warships cruising within 12-NM of these islands/ features without ‘prior permission’ is as much valid as the U.S. FONOPS to uphold its right of military mobility across the global commons. Hence, until such time that the issue of sovereignty over these islands is settled, the legitimacy of China’s stand on FON in these waters cannot be questioned.

Exclusive Economic Zone

Alike in its Territorial Sea, China has never impeded FON of commercial vessels in its EEZ. However, like many other States, China has been objecting to foreign military activities in its EEZ. It may be recalled that in April 2001, China scrambled J-8 fighters against the U.S. EP-3 surveillance aircraft operating about 60 NM off China’s Hainan Island, leading to a mid-air collision.10

Unfortunately, the UNCLOS does not contain any specific provision, either permitting or prohibiting such activities. According to Articles 58(1) and 87 of UNCLOS, the EEZ is part of ‘International Waters’ wherein all foreign warships may exercise High Seas FON, with certain exceptions that relate to economic/ resource-related uses of the EEZ, such as Marine Scientific Research, which may be conducted only if permitted by the coastal State. Therefore, if a foreign military conducts hydrographic surveys in China’s EEZ, it may be justified as being among the High Seas Freedoms since it may be necessary for safe navigation of warships. However, if a foreign military conducts intelligence collection in the EEZ – as China interprets the objective of U.S. military activities in its EEZ – it may be objectionable, at least in terms of the spirit of UNCLOS, whose Article 88 says that “The high seas shall be reserved for peaceful purposes.” Of course, some may consider ‘intelligence collection’ as a normal peacetime activity of a State to bolster its military preparedness to maintain peace. But this only serves to reinforce the prevailing void in UNCLOS, rather than legally deny China the right of ensuring its own security.

Other Areas within ‘Nine-Dash Line’

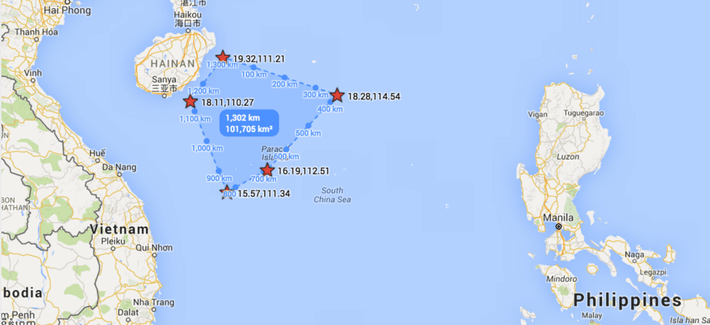

China has never explicitly articulated its stand on the legal status of the sea areas within the ‘nine-dash line’, which lie beyond its 12-NM Territorial Sea and the 200-NM EEZ. However, by laying ‘historic’ claim to all SCS features (islands, rocks or reefs), and referring to all these as islands entitled to EEZ and Legal Continental Shelf (LCS), it has implicitly claimed sovereign jurisdiction over the entire sea area enclosed within the nine-dash line. Based on such assumed sovereign rights – though disputed by other claimant States – China has been curtailing FON in these areas, particularly for warships. For example, in the days leading to the International Tribunal’s verdict on the China-Philippines Arbitration, Beijing declared a ‘no sail zone’ in the SCS during a major naval exercise in the area from 4 to 11 July 2016 (see Fig. 1 below).

As the map indicates, the ‘prohibited zone’ was a sizable 38,000 sq mile area lying between Vietnam and the Philippines. It encompasses the Paracel Islands, but not the arterial International Shipping Lane (ISL) of the SCS.11 During such exercises in the past, China has imposed such restrictions on navigation in the SCS. While some analysts have referred to such restrictions on FON as violation of maritime law,12 given the susceptibility of prevailing international law to divergent interpretations, China cannot be denied the right to interpret law in a manner that best suits its security interests.

However, the above scenario prevailed prior to 12 July 2016. The verdict of the PCA Tribunal has changed all that. The Tribunal has dismissed China’s claim to ‘historic rights’ within the ‘nine-dash line’, indicating that such claims were incompatible with UNCLOS, and asserted that no feature claimed by it in the SCS is capable of generating an EEZ. At least from the standpoint of international law, therefore, Beijing’s claim to sovereign jurisdiction over these areas is decisively annulled. Henceforth, China will need to concede to unimpeded FON in the SCS, both for commercial shipping and warships. For example, if it needs to conduct a naval exercise in the area, declaring a ‘no sail/ prohibited zone’ would no longer be legally tenable. Instead, China could, at best, merely promulgate a mere ‘advisory’ for the safety of ships and civil aircraft intending to transit through the exercise area.

China could possibly react to the adverse verdict of the International Tribunal by declaring an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the SCS. A resort to this would not be constructive since it would further heighten anxieties in the area. Nonetheless, China’s declaration of an ADIZ would be tenable from the legal standpoint. The promulgation of such Security zones is not prohibited by international law. However, for interpreting it as ‘not prohibited, and hence permitted,’ promulgating such a zone must adhere to the spirit of law in terms of its need for maintaining peace or for self-defense, and that it is not obverse to the overarching principle of freedom of navigation and over-flight.

Concluding Remarks

It is amply clear from the foregoing that the contentions over freedom of navigation and over-flight in the SCS are more a result of the geopolitical ‘mistrust’ between China and the other states, aggravated by the voids and ambiguities of international law, rather than any objective failing on part of China and the other states involved to observe the prevailing tenets of international law.

The geopolitical relationships constitute an aspect that China and the other countries involved need to resolve amongst themselves, and the rest of the international community can do little about it. Further, there is hardly a case for convening a fourth UN Conference on the Law of the Sea to renegotiate the UNCLOS, which already is a result of painstaking efforts of the international community during a period that was geopolitically less complex than it is today.

Nonetheless, it is encouraging that the lingering maritime-disputes in the Asia-Pacific are being arbitrated upon by international tribunals. Over the years, the decisions of international tribunals on cases such as the India-Bangladesh (July 2014)13 and the more recent one between China and Philippines on the SCS would be valuable to fill the legal voids, and would firm up over time to add to the prevailing tenets of international law.

China’s adherence to PCA Tribunal’s decision would not only contribute to peace and prosperity in the region, but would also best serve its own national interest, at least in the longer term. However, it remains to be seen how long Beijing will take to assimilate the ‘new normal’ into its policymaking.

Captain Gurpreet S Khurana, PhD is the Executive Director, National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Indian Navy, the NMF or the Government of India. He can be reached at gurpreet.bulbul@gmail.com.

Notes and References

1. ‘The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines V. The People’s Republic of China)’, Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Press Release, 12 July 2016, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf

2. ‘Statement on Award of Arbitral Tribunal on South China Sea Under Annexure VII of UNCLOS’, Ministry of External Affairs (Govt of India) Press release, 12 July 2016, at http://mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/27019/Statement_on_Award_of_Arbitral_Tribunal_on_South_China_Sea_Under_Annexure_VII_of_UNCLOS

3. ‘Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China on the Award of 12 July 2016 of the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration Established at the Request of the Republic of the Philippines,’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Republic of China, 12 July 2016, at http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1379492.shtml

4. ‘China ups the ante, to close part of South China Sea for military exercise,’ Times of India, 18 July 2016, at http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/china/China-ups-the-ante-to-close-part-of-South-China-Sea-for-military-exercise/articleshow/53263905.cms

5. Article 310 of UNCLOS allows States to make declarations or statements regarding its application at the time of signing, ratifying or acceding to the Convention.

6. Office of the Legal Affairs of the United Nations, Treaty Section website (Date of most recent addition: 29 October 2013), at http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm

7. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, No.55, 25 February 1992, at http://www.asianlii.org/cn/legis/cen/laws/lotprocottsatcz739/

8. Limits in the Seas, US Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims, US Department of State (Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs), No 112, 09 March 1992, p.52

9. Rules for Navigation and Sojourn of Foreign Warships in the Territorial and Internal Waters and Ports of the USSR; ratified by the Council of Ministers Decree No. 384 of 25 Apr 1983, cited in Limits in the Seas, US Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims, US Department of State (Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs), No 112, 09 March 1992, pp.56-57

10. Patrick Martin , ‘Spy plane standoff heightens US-China tensions,’ World Socialist Web Site, 3 April 2001, at https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2001/04/spy-a03.html

11. Echo Huang Yinyin , ‘China Declares a No-Sail-Zone in Disputed Waters During Wargame,’ Defense One, 5 July 2016, at http://www.defenseone.com/threats/2016/07/china-declares-no-sail-zone-disputed-waters-during-wargame/129607/?oref=d-river

12. Sam LaGrone, ‘Chinese Military South China Sea ‘No Sail’ Zone Not a New Move’, USNI News, 7 July 2016, at https://news.usni.org/2016/07/07/chinese-military-south-china-sea-no-sail-zone-nothing-new

13, Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration (Bangladesh V. India) Award, Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, 07 July 7, 2014, at http://www.pca-cpa.org/showpage.asp?pag_id=1376

Featured Image: Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (Sept. 6, 2006) – Chinese Sailors man the rails aboard the destroyer Qingdao (DDG 113) as they arrive in Pearl Harbor. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Joe Kane)

CAPT Khurana’s interpretation of UNCLOS regarding both advance notification/permission requirements for innocent passage of warships and military activities within the EEZ are not in keeping with international norms and practice.

His assertion that “many developed countries in Europe” registered similar statements to China’s reserving the right to require prior notification or permission for innocent passage of warships is dubious: Looking through the declarations upon signing or ratification of UNCLOS, the only European states who made declarations similar to China’s were Romania, Serbia, Croatia, and Portugal. Subsequent legislation by Portugal appears to acknowledge the right of innocent passage for warships. In fact, a similar number of states (including Italy, the UK, France, and Germany) registered statements confirming their view that all categories of ships enjoy the right of innocent passage without any requirement of advance notification or permission.

Regarding the supposed “void” in UNCLOS regarding military activity in the EEZ, as CAPT Khurana points out, Art 58 (1) of UNCLOS states: “In the exclusive economic zone, all States, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy, subject to the relevant provisions of this Convention, the freedoms referred to in article 87 of navigation and overflight…” A review of the sovereign rights in the EEZ granted to the coastal state in Art 56 makes clear that they are solely economic in nature, and do not affect military activity. China has based its objection on Art. 58 (3) requiring all states to have “due regard” for the rights of the coastal state, but has produced no evidence that military activity in the EEZ compromises those economic rights in any way. His interpretation of Art 88 as prohibiting military activity in the EEZ since it is not a “peaceful purpose” in the high seas is over-reaching, and would in fact ban all military activity outside of territorial seas, which is neither its intent, nor its common interpretation.

While his analysis of the impact of the PCA ruling is strong, the legitimacy of the Chinese claims regarding innocent passage of warships and military activity in the EEZ is much more contested than his characterization of them as “clearly legitimate” would suggest.