Read Part One here.

By Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt

OVERSEAS PRESENCE

I spoke earlier of the importance we ascribe to the dual-mission carrier in supporting the Nixon Doctrine. It will give more flexibility. When we face opposition at sea, the carriers, now operating both strike and ASW aircraft, can be used to protect the sea lines of communications. When the seas are a sanctuary, as they have been off Vietnam, all the carriers can operate in an air attack role.

These forces can be employed as an advanced force that is capable of rapid commitment, possesses self-contained means of defense, and is easily withdrawn when a task is completed or other forces are deployed.

In this way, Naval projection forces are unique. They can operate as a mobile strategic contingency force—a ready, cutting edge. For instance, if it had been possible to turn over all the air strike effort in Vietnam to land-based air after the first 12 months, we could have pulled out the carriers. It would then have been feasible to reinforce the SIXTH Fleet, which, by showing greater capability from time to time over the past few years, might have proved helpful diplomatically. And we could have created a desirable presence in the Red Sea or Indian Ocean. In another war, at lower force levels, this ability of our projection forces to provide a retrievable strategic reserve after land-based forces are established might well be crucial.

All of a nation’s maritime capabilities bear on its influence around the world and its ability to establish a peacetime presence at a point of choice. We need not look hard to see how the Soviets have translated their naval presence into diplomatic leverage. Their strength in the Arab world today is not entirely attributable to the buildup of their Mediterranean fleet, but it was surely an important factor. The Soviets have, in a sense, successfully turned NATO’s southern flank.

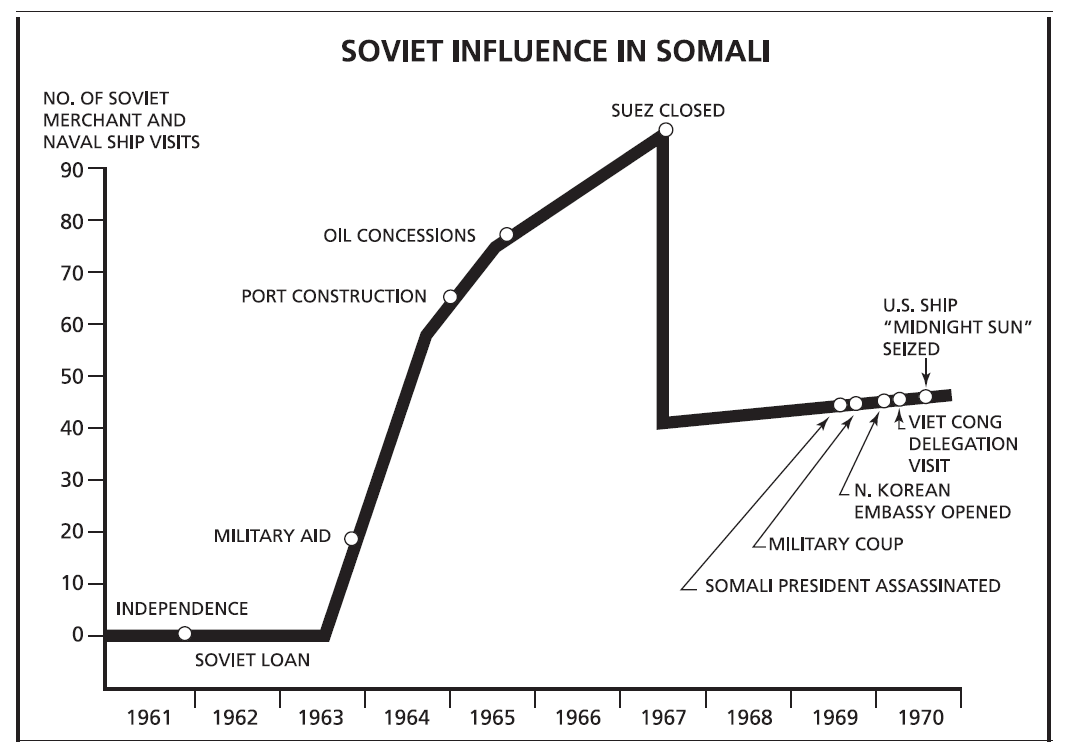

Another area in which the Soviet Navy has supported political influence in peacetime is the Indian Ocean. Somali is a classic case. This chart, correlating Soviet ship visits with internal events, shows how the Soviets have carried on a coordinated economic and diplomatic effort, supported by their merchant fleet and backed by their naval presence. It has been a subtle, piecemeal incursion.

First the Somalis were placed in debt to the Soviets. Next, that indebtedness was used to shackle Somali oil imports exclusively to the Soviet Union. Then, the Soviet-trained army executed a military coup. Finally, the campaign has developed into border harassment of our friends in Ethiopia.

ALTERNATIVE COMBINATIONS OF SEA CONTROL AND PROJECTION FORCES

These, then, are some of the complex considerations that have engaged our thoughts in the past two months as we face important program decisions that determine our course for the future. In our reevaluation of the direction to follow, force options are constrained by an imminent decline in the defense budget and by predictions of a smaller percentage of the national budget for defense in the years ahead. We must find the best combination of the capabilities that we need most. In what has already been said, I have expressed our deep concern that our options are already constricted beyond the point at which we can cope with the threat.

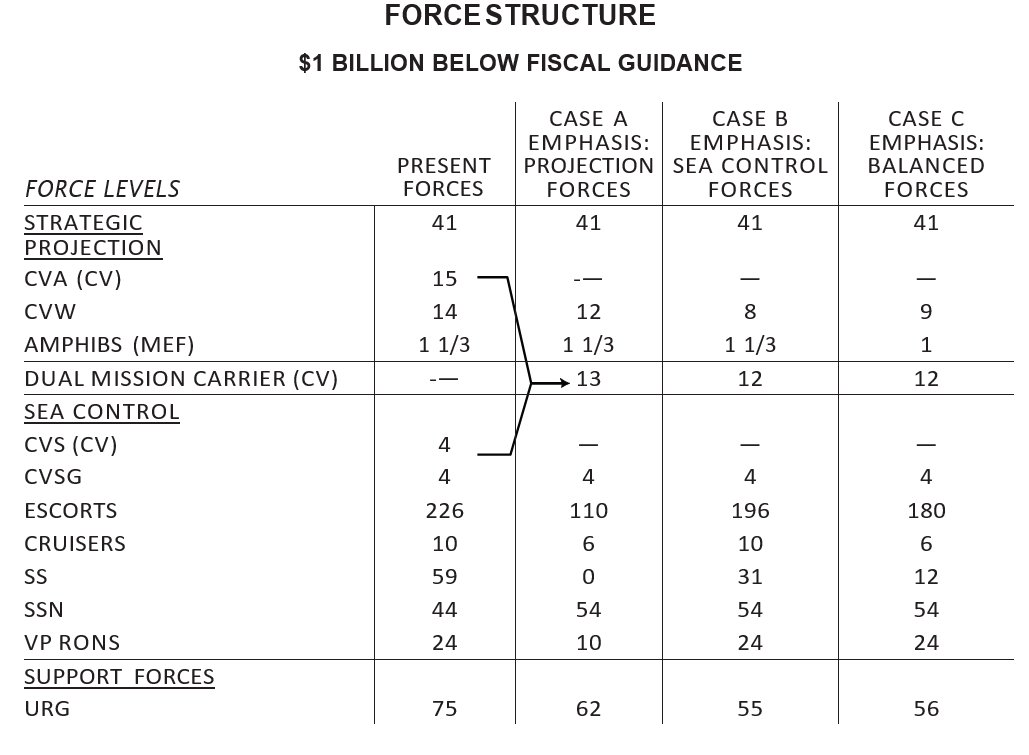

This is an illustrative force, emphasizing projection forces that we could provide in FY-1972 with a budget $1B lower in expenditures than the fiscal guidance. We are not advocating this budget level, and I shall remind you later of my confidence level in maintaining control of the sea with the best Navy we can design with this budget. Here we have categorized our forces by the broad missions they serve, though there is substantial overlap. One example is our dual-mission carrier, which fits, appropriately, in both the projection and sea control groups. Another consists of the cruiser and destroyer, which often project power ashore. The forces are designated here by the missions that will be affected most by marginal force changes.

This Case A force mix has been designed to provide: first, a moderate level of escort protection for our carrier forces and replenishment groups, and, second, minimal protection for amphibious forces. It assumes that we can operate freely at sea, that the Soviets allow us our sea lines of communication. I consider this an unacceptable risk.

Case B emphasizes sea control forces within the same FY 72 budget constraints. Here we do not have enough carriers for the strike mission requirements described previously for the NATO and Asia situations. There has also been a reduction in our ability to provide an attack and amphibious cutting edge as well as contingency force suitable to the Nixon Doctrine.

These examples show that our choice, within these budget constraints, must be one of relative emphasis between sea control and projection forces. In Case C, both are reduced, but with less effect on sea control forces. As with any compromise, neither type of force meets the need adequately. We are faced with the difficult alternatives set forth for you earlier. These alternatives, in our judgment, make it mandatory for the national security that there be no reduction of Naval forces beyond the present levels. I want to remind you now of my view that, while we have a somewhat-better-than-even chance of defeating the Soviets with these FY 70 forces, the forces we can provide in a reduced budget—even at the POM level—lower my confidence of success to about 30 percent.

Prospective budget levels and the implications of the current and growing Soviet threat at sea require us to turn our force structure toward the sea control mission and to reduce accordingly the forces that support other missions. In partial compensation, we must take new actions to encourage the build-up of sea control forces by Japan and by NATO countries that have the requisite maritime skill and potential.

OTHER TYPES OF CHANGE

There are other types of change to which we are giving our attention.

In structuring our Navy for the 1970’s, we shall seek a balance between maintaining present force levels and modernizing for the future. As an extreme example, if we wanted to maintain our present forces at the expense of modernization within a budget of POM minus $1B in expenditures, we would have to eliminate every major procurement. This, of course, is out of the question for two reasons:

- The rapidly improving technical quality of the Soviet Navy, and

- The necessity for a balance—between our present capability against the present Soviet threat, and our future capability against a Soviet threat that not only is growing in quality but shows no sign of significant reduction in numbers.

To be able to concentrate our smaller forces rapidly in a single ocean against a sophisticated power and to meet strategic contingencies as well, the Navy—we are convinced— must have more nuclear-powered ships.

The Navy is committed to several complex and expensive systems, i.e., the SSN-688’s, S-3A’s, F-14’s, DD-963’s, DLGN’s, CVAN’s, and LHA’s. These large programs account for a major part of the budget. Each, however, fits into the pattern of naval capabilities I have set forth. Though each program will be reviewed against the threat and budget environment, I believe that we can and should complete most of these major projects that are now underway. Abrupt changes in direction of procurement are costly and disruptive, and the threat is rising so sharply that we cannot risk a hiatus in the introduction of new, more capable systems.

Some have said that naval missions can be carried out by forces that are much less sophisticated. Some trade-offs, it is true, should be possible, but I am impressed with the need for sophistication in the sea control mission, to counter the high quality submarines being produced by the Soviets. We need sophisticated carrier task forces for defense against Soviet anti-ship missiles launched from either submarines, aircraft, or surface ships. As for our employment of projection forces against third countries: we note that the Soviets have, so far, supplied our opponents with highly sophisticated defensive systems. We shall give this subject close attention and justify in detail all programs of high cost.

- STUDY 6TH FLT DEFENSE

- CV CONCEPT

- MARINE AIR SQUADRONS IN CVWS

- AIR CAPABLE SHIP-LAMPS

- PG’S AND PGH TO MEDITERRANEAN

- DECOYS AND DECEPTION DEVICES

- CAPTOR

- SSN’S AS TASK GROUP ESCORTS

- INTERIM SSM

- SSN WITH SUBSURFACE-TO-SURFACE MISSILE

- HARPOON

- NUCLEAR SAM AND SUBROC PROCUREMENT

- SECURE COMMUNICATIONS

- REVIEW OF ANTI-SHIP MISSILE DEFENSE

- POINT DEFENSE

- BETTER SURVEILLANCE

- TRAINING SUBS

- SPARE PARTS

- CHANGES IN R&D

- ALLIED SEA CONTROL FORCES

- SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT

- CNO EXECUTIVE PANEL

Let me report to you now on some actions we have taken—or are proposing—to increase current capability, speed modernization, and offset the actual and potential reduction in our forces.

As a matter of urgency in view of MidEast developments, we are examining ways to enhance the security of the SIXTH Fleet in the Mediterranean. We need a plan of action that will reduce the risk in the event of a confrontation with the Soviet Union.

A FORRESTAL-class CVA is being prepared for operation next spring as a dual-mission CV.

The Marine Corps will provide aircraft squadrons to operate in carrier attack air wings to make up, in peacetime, for the reduction we are taking in Naval aircraft.

We shall enhance surface ship capability for the sea control mission, in face of the Soviet anti-ship missile, by making surface ships air-capable. A Program Coordinator has been designated for the broad program. This is what we have begun:

- An LPD, with six helicopters, will test tactics and procedures for a new breed of sea control escort.

- An interim LAMPS program will place existing helicopters on DLG’s and a DLGN.

- To prepare for the longer-range LAMPS program and test the feasibility of an interim capability, we shall test an existing helicopter in a DE-1052 class ship.

- We are speeding development of sensors for helicopters employed in the air-capable surface ship.

- The regular LAMPS program for our new DE’s will be accelerated. We may need your help on this proposal. Congress is balking at even the present, modest program.

Before the end of the year, we shall deploy two patrol gunboats (PGs) to the Mediterranean to test their capability in trailing the Soviet missile ships that trail our carriers and other major combatants. This is another action of an interim nature, designed to take some of the initiative from the Soviets, to make them react—as we now must— and to make their operations difficult.

We shall deploy one hydrofoil gunboat (PGH) to the Mediterranean to test its suitability in the trailing role. The results of this evaluation will help in the development of a gunboat that is designed particularly for the mission.

We are increasing ASW R&D for decoys and deception devices and procuring additional torpedo countermeasures equipment to protect our ships.

The Captor mine development program is being accelerated, to give us additional capability against the Soviet submarine. Captor is a deep-moored sensing device that detects a submarine target and fires a MK-46 torpedo at it. It will be useful in our blockade and barrier tasks and may be effective in protecting CVA operating areas against submarine intrusions.

The employment of SSN’s as surface task group escorts will be tested. A program to develop an improved submerged communications capability is being undertaken in support of this concept.

A proposal to develop an interim surface-to-surface missile by 1971, using off-the-shelf equipment—either a drone or a modular standard missile—is being readied. This weapons capability will give our ships a reach comparable to that of the Soviets and cut their advantage in that respect. With the carrier force level reduced, our ships cannot always count on air support, and this action will increase our flexibility in the employment of all our forces.

The Chief of Naval Material is conducting a conceptual design study of an advanced SSN with a subsurface-to-surface missile.

For the long term, a proposal will be made to accelerate delivery of the Harpoon missile system, which can be launched from either aircraft or ships against surface targets. This is the first formal program step toward achieving a requisite capability for both these purposes.

We are reviewing the desirability of removing nuclear surface-to-air missiles from our surface ships and terminating the procurement of SUBROC weapons. The prospective trade-off is an increase in our conventional capability.

The procurement of secure communications equipment is being accelerated, to give our ships and aircraft greater freedom of action. This measure, like others, will afford us the greater unit effectiveness that our smaller forces must have.

Defense against the entire spectrum of threats posed by the Soviet anti-ship missile to our task groups and convoys is under study. We are not convinced that our resources for defense are being used efficiently or effectively, and we are going to establish an office with authority and responsibility for centralized direction. We are looking at active and passive electronic warfare, command and control, communications, air and surface weapons, and new sensor areas, so as to match our response most effectively to the threat. As this matter is sorted out, we shall report to you with specific proposals.

We have begun to speed installation of the Basic Point Defense Weapons System and to develop the close-in Vulcan Phalanx gun system. We will thus increase our active defense against current Soviet missiles at low cost, while we seek solutions to the longer- range threat.

A smaller Navy must have better information and intelligence. We are establishing a group to look into the near- and long-term possibilities of better surveillance—both in satellites and underseas—including more effective use of the information already available from multiple sources. I expect a report within a month. In this area, our present view is that strong support from you and funding at relatively low levels could make a significant change in our favor in the power relation at sea.

If required by budget reductions, we are planning to decommission 35 conventional submarines, which now provide about 70 percent of our target services. We propose to retain 10 of these submarines at very austere manning levels and to reclassify them as ATSSs or target submarines. By taking similar action with an additional 7 conventional submarines of the active fleet, we are able to trade-off operating costs and have 17 target submarines with no additional requirement for funds. We thereby, of course, accept some loss of initial wartime combat capability.

To improve spare parts support, and thus material readiness, we are studying the desirability of reprogramming FY 71 funds to rebuild the spares inventory. Last year, an average of 6 percent of our ships were not ready for combat because of spares deficiencies.

We are modifying our investment in research and development. In FY-1972, the changes in emphasis will amount to about $90M for ASW and about $150M overall.

In pursuing the question of encouraging our allies to build-up their sea control forces, I have asked Admiral Colbert of the Naval War College to examine the need and possibilities. When his survey is complete—within two months—I shall recommend specific measures.

On the systems management side, we are emphasizing the Project Coordinator/Manager concept to deal with options that cut across all the complex disciplines of naval warfare. This concept—as exercised in the past—proved not effective enough; we are investigating ways of providing authority to go with the responsibility. We have already taken steps to ensure that successful project managers stay with their programs and receive promotion recognition.

You will note that these actions look to the present and to the future. They represent an initial program against the primary threat to our control of the seas. Though improved efficiencies in our use of forces may result, I refer you to my earlier remarks, pointing out that any of the potential reductions in our forces leaves the Soviets with the advantage at sea. The prospect that the momentum the Soviets have generated will lead to significant new developments is our primary concern. We must invest heavily in the future, even if we must pay for it by reducing current force levels.

To provide a better sense of direction for research and development, and promote force and strategic planning, I have created a special group, to be known as the CNO Executive Panel. The panel will work directly for me in developing a long-term concept for the Navy and in reviewing our current programs to make sure that they are consistent with that concept.

We are also reviewing the Navy’s support structure and identifying special budget problems, so as to eliminate all expenditures that do not contribute to Naval readiness.

You are familiar with the problems we are encountering in scaling down our base and support facilities. Our current survey seeks to reduce overhead while providing a hedge against any future requirement for buildup. This analysis is nearing completion, and we shall come to you soon with a proposal for major savings in the consolidation and closure of facilities.

Similar work, now in progress, will lead to changes in the Navy’s general support activities—base operations, training, logistics, command, medical, and individual support. These activities account for 35 percent of the FY 72 POM Annex Navy budget, a substantial increase from the 29 percent of FY 64. We are looking at the factors that have caused this increase. We are also establishing procedures to consider support and force implications simultaneously, providing a degree of effectiveness that has not been possible till now. In the meantime, our planning assumes that general support for each force category will be changed approximately in proportion to the changes in force level.

The Navy has a special problem in a serious expenditure hump in FY 71 that could induce even deeper cuts in force level. For example, a delay of several months in required decisions on inactivations of ships and reductions in civilian employment would cost the Navy on the order of $75M. Our FY 71 budget is already tight, and trade-offs for the $75M will be hard to find. Rumors are rife in the fleet; the uncertainty has created serious morale problems, with attendant effects on personnel retention. We need your help and shall continue to work closely with you on this.

We face a similar problem in out-year level funding. Inflation—at current or reduced rates—amounts to a cut in defense resources. For example, a 5% inflation effectively cuts $1B from the Navy budget and reduces the size of the Navy that can be supported.

The change of direction that I have described will not improve our exercise of power at sea unless we are able to manage our personnel better. We must set a clear purpose within the Navy. We must make naval service more attractive. I think measures to achieve these goals offer the greatest single potential payoff in increased combat readiness. Nothing less than an all-volunteer force will be acceptable.

Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt served as the nineteenth Chief of Naval Operations of the U.S. Navy, from 1970 to 1974.

Featured Image: The U.S. Navy Aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) underway in the Tonkin Gulf in November 1972. The Big E, with assigned Carrier Air Wing 14 (CVW-14), was deployed to Vietnam from 12 September 1972 to 12 June 1973. Alongside steam the guided missile cruisers USS Long Beach (CGN-9), USS Truxtun (DLGN-35) and USS Bainbridge (DLGN-25) (from top to bottom). (Wikimedia Commons)