As observers thankfully have noted, piracy off the coast of Somalia dropped significantly over 2012. As Mark Munson points out, a variety of factors contributed to this decline. These included an increase in armed guards aboard commercial vessels, continued international naval patrols in the region, attacks by some of those international naval forces on pirate havens, and operations by the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF).

Yet it would be too easy to write off piracy in the area as a dead issue. Despite some glaring examples to the contrary, pirates are not uniformly stupid, as demonstrated by the $160 million they made in ransom in a single year. They are capable of adapting to change in their maritime operating environment. For example, when the world’s navies began patrolling the area, pirates attempted to disguise themselves as innocent fishermen. International naval forces reacted by conducting more thorough searches and seizures of suspected pirates, who in turn adapted by using motherships to expand their area of operations beyond the patrol areas. Despite increasing the transaction costs for both the pirates and international naval forces involved in this conflict, this “tit-for-tat” process did not slow or halt the increase in piracy.

Several analysts believe that the increase in armed private security guards aboard commercial ships in the region played a key role in reducing piracy; at least 40% of commercial vessels in the region had armed guards aboard at the beginning of 2012. Although armed guards did in fact contribute to the drop in piracy, their dampening effect merely shifted the onus back to the pirates to continue measure/counter-measure evolution. There’s little to stop them from adapting to this tactical change as they adapted to those that came before, for instance by using more personnel to overwhelm ship defenses, or mounting a stabilized light machine gun to deliver greater and more accurate fire against ships. Rather, it’s two other factors that have been the main cause of the drop in piracy in Somalia: attacks on pirate safe havens from the offshore EU task force and more operations by a better trained PMPF.

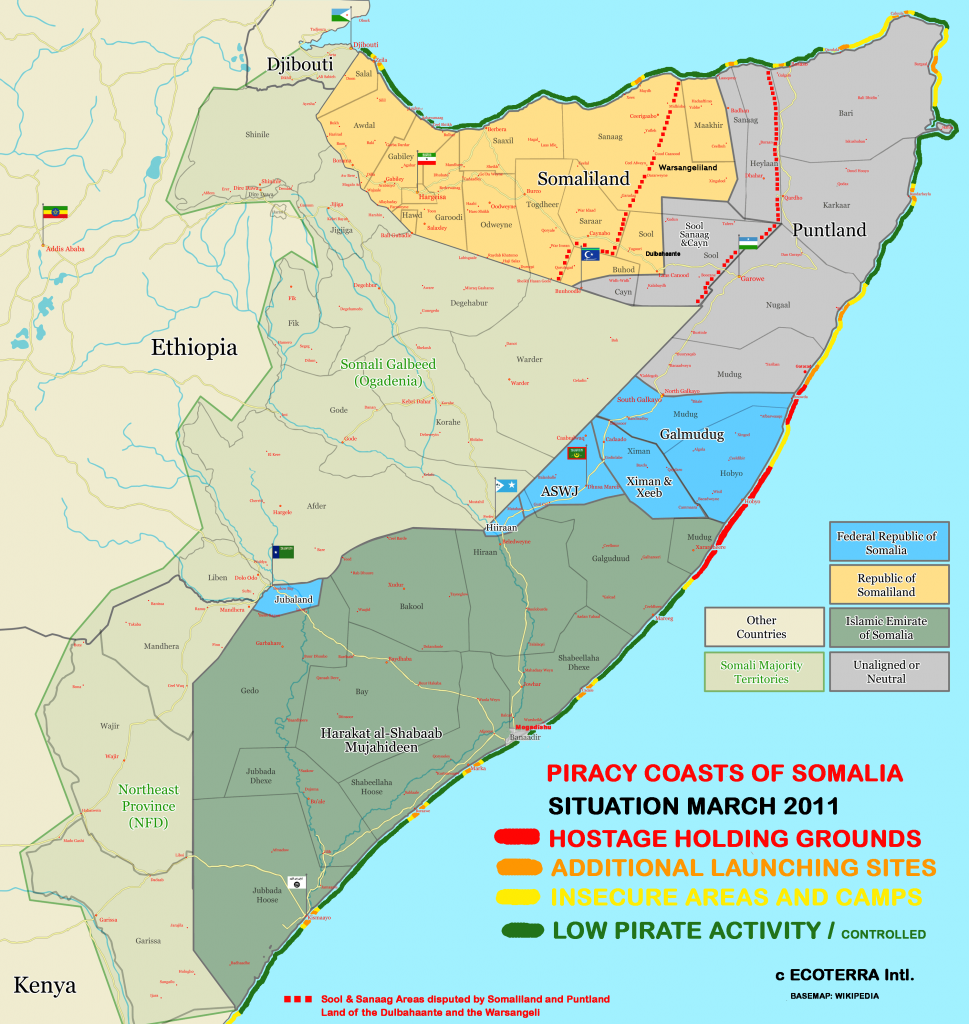

In May 2012, EU forces attacked the pirate safe haven Haradhere, one of the largest pirate bases in one of Somalia’s notoriously ungovernable regions. This was the start of the EU’s counter-piracy targeting pirate safe havens with surgical and extremely precise strikes. It was also a key development in the region as the first strike ashore by any patrolling international naval forces (with the exception of a handful of hostage rescue missions). By targeting the pirates at their center of gravity, EU forces were able to damage their logistics and raise the cost of doing business, which in turn disrupted their operations.

However, these strikes have two main shortfalls. First, they are difficult to conduct at a high tempo because of the time it takes to locate the strongholds, plan the strikes, and carry them out while ensuring minimum collateral damage; being based afloat only lengthens the timeline. Second, the surgical requirements for the strikes allow pirates to react by surrounding themselves with even more civilians, making the strikes all the more difficult.

Unlike the EU’s strikes, the PMPF attacks pirate strongholds from land. Trained initially by Saracen International/Sterling Corporate Services (which was led by Australian Lafras Luitingh, an experienced intelligence officer with from South Africa), the PMPF are arguably one of the most well-trained paramilitary forces north of Mogadishu. Although they are still categorized as a backwater paramilitary force, Sterling Corporate Services created this simple force that outclasses its pirate adversaries (however due to behind-the-scenes political moves it is unclear who, if anyone, now trains them). Consequentially, the PMPF has been able to patrol the littorals in Puntland and attack pirate bases. Although the PMPF lacks the firepower of the EU task force, they are able to permanently station themselves in areas prone to piracy and use their knowledge of the area to recognize and pursue pirates. Nevertheless, the PMPF’s main weakness is whether they have the capacity to sustain themselves and their capabilities without foreign funding and guidance from their former trainers.

Applying These Lessons Elsewhere

The fight to stop piracy in Somalia is not over but lessons learned can be applied to other areas, such as the Gulf of Guinea, where piracy is on the rise. These lessons are that changing the pirate’s operating environment alone will not eliminate piracy, as the pirates can and will adapt accordingly. Instead, the problem must be solved on shore by going after the pirate center of gravity—their strongholds—to effectively disrupt their operations. Although offshore attacks against these strongholds can yield some results, developing a disciplined local paramilitary force with greater capabilities than the pirates will disrupt their operations even more. Creating such a force in a weak or failed state is difficult and is fraught with the danger of backfiring, but as demonstrated by the PMPF, it is not impossible. Will the U.S. Navy and other international maritime forces pursue these proactive options in future areas where piracy becomes a problem? Or will costly international task forces reactively patrolling offshore remain the norm?

Bret is a student at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. The views expressed are solely those of the author.