Deterrence and Defense

In Germany, few people understand that defense and deterrence are still tasks for NATO. We are surrounded by friends. But talk to our allies from Norway, Eastern Europe, and Turkey and you find their feelings are quite different. Norwegians and Eastern Europeans fear Russia. The Turks have worried about Iran and are now concerned about Syria. NATO’s Patriot deployment to the Turkish-Syrian border proves wrong all who argued that the era of collective defense and deterrence is over.

In addition, “nuclear sharing” is still appropriate, even if Germans with their excessive desire for disarmament do not like it. If some of our allies sleep better due to U.S. tactical nukes based on our soil this is a price we have to pay. In an alliance based on the all-for-one principle, nuclear sharing is necessary as long as a single ally considers it important for his security.

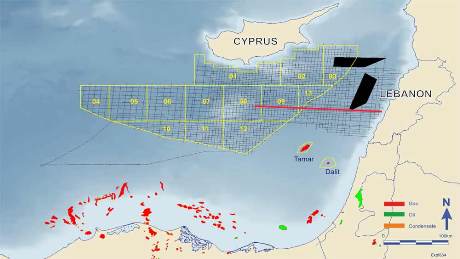

|

| Range of Saudi CSS 2 missiles (Source) |

Deterrence by denial will provide NATO more workload. The latter means to prevent an adversary from acting aggressive by making his means useless through one’s own capabilities. In particular, this applies to missile defense, but not only with regard to Iran. Saudi Arabia also has sophisticated medium-range missiles. If Saudi Arabia falls apart and “turns Egypt,” it can hardly be guaranteed that Saudi MRBMs will not fall into a bad guy’s hands. Moreover, Russia’s fears about missile defense are nonsense. U.S. missile defense’s final phase in Europe has just been cancelled. In addition, the U.S. is almost broke, and it is unclear how much new government revenue the “Shale Gas revolution” actually brings. It is therefore very unlikely that Congress would approve a new budgetary disaster.

Nordic Air Policing

The Baltic countries lack their own air forces. Thus, NATO is providing security for their airspaces. Moreover, Russia is increasing its number of assertive air patrols in the Baltic and the Arctic, while all NATO/EU countries in the High North have budgetary problems to sustain numbers and operational readiness of their fighter aircraft.

Hence, it would make sense for operational and for strategic reasons to establish a Nordic Air Policing mission from the Baltic over Denmark, Norway, and Iceland to Greenland, maybe even including the UK as lead nation. Non-NATO-members Sweden and Finland should receive an offer to join. Moreover, the positive side effect would be the outward-drifting UK could be linked to European security.

Special Operations Forces

Due to the political hazard of Iraq and Afghanistan, along with austerity, the era of major NATO land campaigns is over. Syria tells us that Western decision makers will try to avoid at any cost sending combat troops to foreign ground. Training and support missions, as the EU is doing in Mali and Somalia, will be the West’s approach, at least until the end of the decade. While the EU is doing well with training missions, it lacks experience with special operation forces (SOF). However, NATO’s SOF headquarter is running very well. Therefore, there is considerable potential for NATO-EU work-sharing. The Union could do basic military training, while the Alliance focuses on SOF training including partnerships with Non-NATO-countries.

Future Western land campaigns – if ever given a go by decision-makers – will follow a “light footprint” approach, which perfectly suits SOF. They will mainly carry the operational burdens. It is in all member states’ interest that NATO provides the framework for interoperable SOF.

Maritime Security and Naval Operations

The Standing NATO Maritime Groups are an unparalleled, but unnoticed success story. Since their creation beginning with SNMG 1 in 1968, the two SNMGs and two Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Groups (SNMCMGs) have done their job without causing any political tensions. Instead, they were ready to go when called, like the 1999 Allied Harvest mine-clearance effort in the Adriatic Sea after the Yugoslav bombing campaign, or in front of Libya during Operation Unified Protector in 2011.

Naval operations are a niche where NATO is preeminent, due to operational experience and U.S. assets as a backup. However, the EU could try to seek a way into this niche by playing on the lessons learned from Operation Atalanta. Plagued by failures in security policy (e.g. Mali and its battlegroups), some EU fans may conclude that naval operations are a sector where the EU could better play of its success. But the EU does not have such operational experience in maritime affairs as NATO does, nor has it any access to U.S. assets. If things go wrong, NATO would receive a U.S. military bailout, the EU would not. Thus, naval operations should be left to NATO, while the EU focuses on the civilian side. In times of austerity, we do not need two organizations competing in the same field. Operation Unified Protector showed the enduring worth of the capability for rapid maritime crisis response. With a look on the instability in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, scenarios for new maritime operations in front of North African shores cannot be ruled out. Hence, SNMGs and SNMCGs should be excluded from defense spending cuts. Beside the Strait of Gibraltar, the focus of NATO’s maritime presence should be the Eastern Mediterranean. Trouble is likely due to the civil war in Syria and tensions between Turkey, Lebanon, Cyprus, and Israel about offshore gas. Russia is seeking to implement an anti-access/area-denial strategy by its largest naval expeditionary operation since the USSR’s collapse. Thus, a show of force and demonstration of political will by NATO is a necessity. After 2014, the Eastern Mediterranean is going to be the operational area for NATO’s seaborne missile defense on U.S. Aegis-destroyers.

We are right at the beginning of an Indo-Pacific-Century. Thus, when it comes to maritime security – I am explicitly not talking about air and ground forces – NATO should look more East-of-Suez. The Alliance has been present at the Horn of Africa since 2008 to protect the World Food program’s vessels and to fight piracy. NATO outreach to Asian navies, in particular China, has already begun. It would not make sense to cut these tiny, but very important strategic ties by ending NATO’s navel presence at the Horn of Africa.

|

| British warships East of Suez in 2012 (Source) |

Right now, Britain and France are pursuing their own track in the Indo-Pacific, while the EU is not taken seriously there in terms of security issues. However, as NATO’s present Maritime Groups will busier in the Mediterranean, a considerable option is to base a new third SNMG in Djibouti. The strategic values would be; permanent protection of vital sea-lanes; ability of rapid power projection and crisis response towards the Persian Gulf; quickly available means for disaster relief; mutual trust building by naval diplomacy with emerging maritime powers like China or India; a virtual capacity to reach out east of Malacca.

Of course, in many member states, especially Germany, such ideas about new NATO forward presence would be extremely out-of-favor. Thus, a more realistic approach is just to never end Ocean Shield. Open discussions about the operation should be avoided. While little attention is given, the mission can evolve in the ways mentioned and, hence, create irreversible facts.

The Arctic, however, should not be subject to military considerations other than Air Policing. Engaging Russia and new Asian stakeholders in the High North is a political question. The worst possible mistake would be to militarize and thereby to complicate Arctic politics.

Export and Guarantee Stability in Europe

After the Cold War’s end, the export of stability to Eastern Europe and the Balkans has been an outstanding success. While the Nobel Peace Prize has been given to the EU for incomprehensible reasons, it was NATO that connected past adversaries into its framework of peace, stability, and security. Macedonia and Montenegro should join NATO, once all membership criteria are met. In the medium term, the door should also be open to Bosnia, Serbia, and Kosovo. The more Balkan countries in NATO, the better, because it significantly decreases the likelihood of conflict in the region.

Georgia and Ukraine are not yet close to NATO membership, but the door should not be closed. The Georgians have a pretty tough road ahead. They will never join NATO as long as there are Russian troops on Georgian territory. Thus, either they find a way for the Russians to leave (which Moscow will not do) or they have to give up Abkhazia and South Ossetia as a prize for their way into NATO and EU (which Tibilisi will reject).

With regard to Russia’s resurgence and emerging assertiveness, Sweden and Finland should be offered closer partnerships or full memberships, if they so choose. To prevent Cyprus from becoming a Russian proxy, it would be a great idea to bring them into NATO. Unfortunately, Turkey would not let that happen. If they really go for independence, membership for Greenland, Scotland and Catalonia in NATO should be granted. (Although the Spanish stance on Catalan NATO/EU-membership after a succession would be quite interesting to watch).

|

| EU youth unemployment 2013 (Source) |

Europe’s crisis has been managed, but is far from being solved. In 2009/10 – surprise, surprise – the trouble in Greece occurred a few weeks after the German elections. We will see what happens after Merkel has been re-elected on September 22 or after the elections to the European Parliament in May 2014. It is an open secret in Berlin that Greece needs a second haircut. New bailouts for Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, and Italy are still on the table, but before September 22 nobody wants to talk about such issues. The fatal consequences of the huge youth unemployment have not occurred much yet, but they will eventually. Last but not least, when the United States is back on track with an economy running “full steam ahead,” France will still be discussing retirement in the age of 62. After ISAF’s end, one of NATO’s main missions is to be a backup for stability in Europe, if turmoil in the Euro Zone or even EU takes charge.

Keep the Russians and Chinese Out

There are these debates about Chinese bases in the Atlantic – which the author has been part of – and a new Russian naval presence in the Mediterranean including a base in Cyprus. There are reasonable arguments for the position that these debates are not kind of close to reality. However, the fact that such debates are now possible, which they would never have been ten years ago, should raise one’s attention.

Except the Soviet/Russian Westgroup from 1990-94 in Germany, a Non-NATO/EU-country has never had a permanent military presence in a NATO/EU-country. If Russia, China or someone else finds a way to set up a permanent military presence in a NATO or EU country, it would a dramatic signal for Western decline. NATO’s decision makers and strategists are tasked to prevent that from happening at any cost.

Felix Seidler is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany, and a German security affairs writer. This article appeared in original form at his website, Seidlers Sicherheitspolitik.

However, geostrategic realities on the Korean peninsula and in the Persian Gulf might be more complex than they appear. On the peninsula, the two Korean states

However, geostrategic realities on the Korean peninsula and in the Persian Gulf might be more complex than they appear. On the peninsula, the two Korean states