- The battlefield is not the only place our defenders die.

Within the Air Force, there is no cow more sacred, no shibboleth greater, than the glory that is the manned fixed-wing combat aircraft. While even the most obstinate fighter pilot might be willing to concede that unmanned aircraft will necessarily make up the majority of a future force, such pallid (even bloodless) prospects are loudly lamented. Valor and heroism cannot be had from an armchair; Sic transit gloria Air Force.

Within the Air Force, it is the danger and thrill of piloting (and the concomitant safety and tedium of remote combat) that justifies the continued marginalization of the RPA community from promotions and awards. Certainly, flying RPA is less exciting than flying a F-18. But, as a career, is it actually that much less dangerous?

It’s not hard to imagine, early one morning, an IED going off on the road to Creech AFB, blowing up a commuter bus full of RPA pilots on their way to work. How different would the conversation about a “drone medal” have been in the wake of significant combat casualties? Such a scenario isn’t just possible – it’s one America’s enemies are actively trying to bring about.

Critics might say that this is just a hypothetical, which is true. It’s exactly as hypothetical as a fast-mover being brought down by enemy fire in post-invasion Iraq or Afghanistan, which is to say that it’s a possibility which has never occurred. For these two wars, “combat risk” has been as hypothetical for F-16 pilots in Iraq as for RPA pilots in Nevada. But even if we accept that fixed-wing combat aircraft are working in a very low risk combat environment in Iraq and Afghanistan, what about all the other dangers of flying? While, a differential risk analysis still supports the conclusion that flying RPA in combat is only marginally less dangerous than flying manned fixed-wing combat aircraft.

Now, I can almost hear the jaws of fighter jocks hitting the floor. How could armchair warfare approach the danger of conducting close air support over hostile territory? The answer is: cumulatively. Now, the Air Force should be more amenable to this line of thinking than the other branches of the armed services. During WW2, the Bronze Star was created to raise the morale of infantrymen who were disheartened by the Air Medal. As George Marshall said in a memo to Roosevelt, infantrymen “lead miserable lives of extreme discomfort and are the ones who must close in personal combat with the enemy.” And yet, this viewpoint mostly originates from a skewed view of what risk is. It’s true that your average WW2 infantryman faced individual moments of tremendous danger, punctuating long bouts of boredom. Given the personal courage required to maintain effectiveness in the face of the enemy, it is easy to see why infantrymen could be dispirited by medals going to bombardiers flying safely miles above the battlefield. But, while the risk of any particular bombing mission was relatively low (over Germany, about 5%), it was the cumulative risk that was so valorous – only one crewman in six was expected to survive his tour intact. The courage of the infantryman consisted in doing an exceptionally dangerous thing a few times; the courage of a bombardier, in doing a mildly dangerous thing many times.

If the modern student of war can understand why the infantryman’s courage cannot be privileged over the air crewman’s, he can come to see why the manned pilot’s valor cannot be preferred to the unmanned, in both the current wars and the wars to come. First, combat looks very different in asymmetrical wars like Iraq and Afghanistan. In twelve years of combat, we’ve lost a whopping one fighter jet to hostile fires in the air, in 2003. In both wars, we’ve lost a total of 18 fixed-wing fighter aircraft (almost all due to human errors or mechanical failure), and six of those pilots have died. Although each of these deaths is tragic, six fatalities in two wars over twelve years is hardly an epidemic, and these deaths account for a tiny fraction of all airmen who have died over these twelve years.[1] Moreover, only one of these deaths was caused by enemy fire, largely due to the fact that, since 2003, the enemy has had zero capability to shoot down fast-movers. From a statistical standpoint, since the defeat of Saddam’s air defense weaponry, ~0% of the risk to manned fixed-wing combat aircraft has come from enemy fires – all of the risk is due to the general risks associated with flying. This is not to say that flying is not dangerous – over the past ten years, there have been an average of 8.2 fatalities a year (though most of those fatalities come from multi-death incidents). But for fast-movers in particular, none of the risk comes from combat or deployment.

What then, are the primary dangers to airmen? The data unequivocally says motor vehicle accidents (52 fatalities in 2012) and suicides (over 100 in 2011), [2] and on the rise) kill the most airmen every year. Nor are these two kinds of casualties equally distributed across occupations. Because most of the data is hard to get at, the following are sketches of arguments, suggestive evidence open to empirical verification.

Ironically, one of the “perks” of being an RMA operator – not deploying and instead commuting to work every day – almost certainly will, over time, kill more operators than flying manned planes would. According to a NATO morale survey[3], a significant number of Reaper/Predator pilots complained about the long commutes to the bases where they work (meaning they had commutes of over an hour). Combined with high levels of work-related stress, long shifts for months on end, and unhealthy sleep schedules, this driving substantially raises the risk of a vehicular accident (though exactly how high, it’s difficult to say). Manned fixed-wing pilots have some of the same work issues as unmanned pilots, of course, except that they are deployed for months at the time when their occupational stress is the highest (and when they would have the highest work-induced risk factors for a vehicular accident). It’s a little counterintuitive, but when your main job (flying combat sorties) has become surprisingly safe, the risk starts to come from weird, other factors.

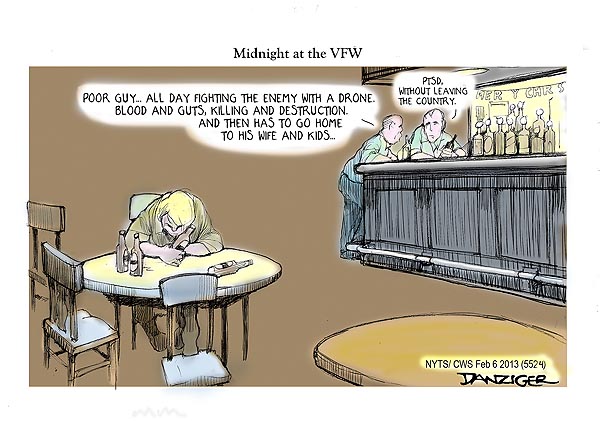

Now, I don’t mean to suggest a perfect equivalence between a pilot who dies in a car crash on his way to work and one who dies flying in an operation over Iraq (rare as that is). But risk analysis demands that we also take lots of small risks over time to be serious and meaningful. An airman fatigued from piloting a Predator for 12 hours straight who dies in a crash at 2am on his way home from Creech AFB has “paid the ultimate price” just as surely as a disoriented F-18 pilot who makes a fatal maneuver. And some of the risks from driving that airmen face are operational –they come from the pace and intensity of their work. [4]

While added driving risk is difficult to tease out, suicide provides a much more personal face to a 21st century understanding of what combat risk is. Our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan might be the first in history where the number of suicides exceeds the number of combat deaths. Because that the Air Force doesn’t publish casualty breakdowns by Air Force Specialty Code (though a FOIA request might dislodge them), it’s impossible to say what the suicide rate amongst only pilots has been. But we do know some things about it from other research.

Mostly, we know that the suicide rate amongst pilots (RPA and Manned) is lower than the rest of the Air Force; pilots are officers and are selected for physical, mental and moral capabilities, both of which reduce risk factors for suicide. But, of course, the risk factors for individual pilots vary depending on their circumstances. One of the biggest risk drivers of suicide for veterans is PTSD, which one study showed to make someone ten times more likely to successfully commit suicide.[5] And a number of recent studies have shown that RPA pilots are at an increased risk of PTSD and work-related stress. A NATO study found low morale and high levels of operationally-induced stress in Pred/Reaper crews.[6] More significantly, a retrospective cohort survey found that RPA pilots have higher levels of PTSD and other mental health diagnosis compared to manned pilots.[7] Absolutely, they face a 60% increased chance (in this admittedly limited survey) of a mental health issue, although adjustments for age and experience brought that number back towards the baseline.

Unfortunately, despite a fairly extensive search of the data available online, it’s hard to drill down more on the number of suicides afflicting pilots. But it’s sort of irrelevant, because I can still lay out my basic conceptual case for a new way of thinking about risk. The case that being an RPA pilot isn’t much less dangerous than being a fighter pilot is pretty simple. In low-intensity conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan, the hostile fires-risk part of a fighter pilot’s job approaches zero, leaving only the risk of flying (~1 Class A mishap/100k flight-hours). On the other hand, while a lot of the data is still coming in, we know that being an RPA pilot carries its own set of real, physical risks. The geographical placement of AFBs where RPA pilots work and the increased stress of their jobs takes a physical toll. Over time, those risks will add up to deaths. Given that, for fighter pilots in particular, the going fatality rate seems to only be about 1-2 per year, it is logical to conclude that the combination of increased motor vehicle risk and suicide risk could render RPA more dangerous than flying, over time. This hypothesis is empirically testable (albeit using data the Air Force hasn’t made available), and it may be worth following up on this post with further research.

Unfortunately, despite a fairly extensive search of the data available online, it’s hard to drill down more on the number of suicides afflicting pilots. But it’s sort of irrelevant, because I can still lay out my basic conceptual case for a new way of thinking about risk. The case that being an RPA pilot isn’t much less dangerous than being a fighter pilot is pretty simple. In low-intensity conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan, the hostile fires-risk part of a fighter pilot’s job approaches zero, leaving only the risk of flying (~1 Class A mishap/100k flight-hours). On the other hand, while a lot of the data is still coming in, we know that being an RPA pilot carries its own set of real, physical risks. The geographical placement of AFBs where RPA pilots work and the increased stress of their jobs takes a physical toll. Over time, those risks will add up to deaths. Given that, for fighter pilots in particular, the going fatality rate seems to only be about 1-2 per year, it is logical to conclude that the combination of increased motor vehicle risk and suicide risk could render RPA more dangerous than flying, over time. This hypothesis is empirically testable (albeit using data the Air Force hasn’t made available), and it may be worth following up on this post with further research.

This analysis also makes a broader point. The Air Force has reached a point where heroism can no longer really be understood by amounts of physical risk. Though outside the scope of this post, enlisted AF technicians who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan and whose duties took them outside the wire were manifestly more subject to combat risk than the pilots deployed to support OEF and OIF. We have been fighting wars where physical risk has not necessarily most heavily accumulated to those doing the actual killing (e.g. C-130s, not F-15s, are subject to hostile fire). What this reveals is something that was probably true all along. We need to stop idolizing risk and realize that we should make heroes who look like the excellences we need. The sacrifices that C-130, F-18, and MQ-9 pilots make to perform excellently and serve their country well are all going to look a little different. It’s long past time to stop privileging one view of heroism.

[1] Air Force Safety Center, 7 &d 19

[2] Many accidents are actually suicides. Cf. Pompili et al (2012), Car accidents as a method of suicide: a comprehensive overview, Forensic Sci Int.

[3] Psychological Health Screening of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operators and Supporting Units, 2011

[4] Combat exposure, too, has a role to play (http://www.journalofpsychiatricresearch.com/article/S0022-3956(08)00003-4/abstract).

[5] Gradus et al (2010), “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Completed Suicide”, Am J of Epidemiology.

[6] Psychological Health Screening of Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Operators and Supporting Units, 2011

[7] Otto et al (2013), “Mental Health Diagnoses and Counseling Among Pilots of Remotely Piloted Aircraft in the United States Air Force”, MSMR.