Regional Strategies Topic Week

By Michael van Ginkel

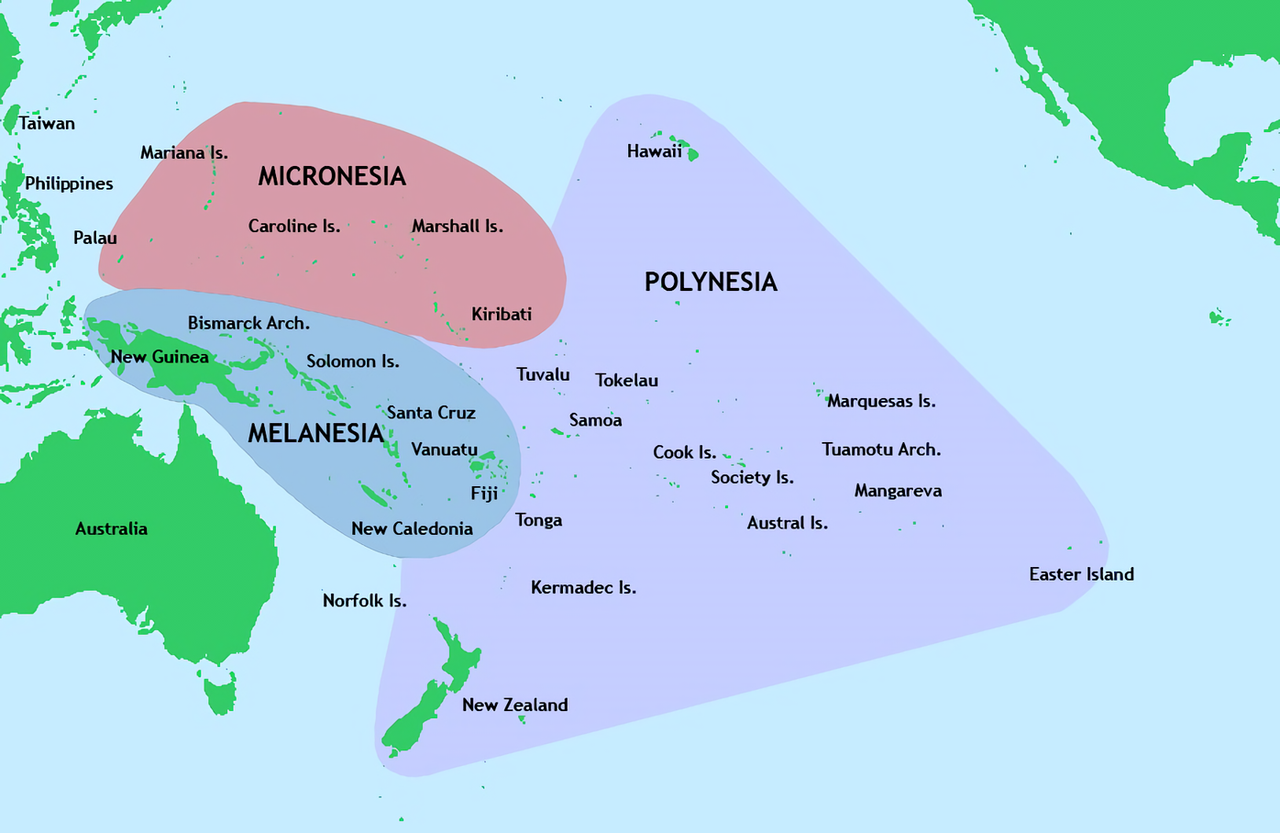

Archaeological records of South Pacific islands point to almost 5,000 years of occupation. Across Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia, the archipelagic geography forced inhabitants to develop a heavy reliance on marine resources and maritime trade. In 2010, the fishing and tourism sectors alone amounted to around 10 percent of the annual gross domestic product (GDP) of the Pacific Island Countries and Territories, or roughly $3.3 billion. During the 2014 workshop entitled “Regional Security Architecture in Oceania held in Vanuatu,” participants highlighted the important links between economic prosperity and human security in the maritime domain.

To address the non-traditional threats undermining maritime-based economies, island nations and regional multilateral frameworks have implemented programs around maritime capacity-building, information-sharing, and security assistance operations. These initiatives provide opportunities for further development by local leaders, and for foreign entities to contribute resources, assets, and training toward South Pacific maritime security with efficiency and efficacy. By aligning future efforts with the most pressing needs of existing maritime institutions and initiatives, stakeholders can effectively address the threats to the South Pacific livelihood posed by non-traditional security challenges in the maritime domain.

Overcoming Limited Maritime Law Enforcement Capacities

A paucity of maritime law enforcement assets has hindered attempts to adequately monitor coastal waters, enforce licensing and regulations around fishing and aquaculture, and intercept smuggling and trafficking. Palau, for instance, only has one 30-meter offshore patrol vessel to patrol an exclusive economic zone of around 629,000 km2. The small island nations likewise suffer from deficiencies in supporting infrastructure, including drydocks and human resources, that could reinforce maritime law enforcement operations against illicit activities like drug smuggling, human trafficking, and illegal, unreported, and unregistered (IUU) fishing.

As a result of this gap in enforcement capacity, IUU fishing has proven particularly costly to South Pacific island nations in terms of environmental impact, catch-rates, and national GDPs. In some instances, however, local institutions have used technological approaches to monitoring for IUU fishing to compensate for low numbers of patrol vessels. In Tonga, the Pacific Island Forum Fishery Agency, the inter-governmental agency responsible for compiling and disseminating South Pacific fisheries data, manages the island’s vessel monitoring system. The data facilities the ability of Tonga’s law enforcement agencies, including the Police Ministry, Customs Office, Transportation Ministry, and Tongan Defense Services, to enforce legislation around fisheries. In general, the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) has arisen as a unifying organization for formulating and implementing maritime initiatives in the South Pacific, including in fisheries, development, and tourism. By continuing to spearhead initiatives in conjunction with South Pacific island governments, the organization can work to enhance local maritime security.

Foreign entities can maximize their impact by contributing to existing security arrangements after a careful assessment of maritime threats and law enforcement capacities. For example, to offset the insufficient number of Tonga law enforcement vessels available for patrol, the United States signed an agreement where Tonga officers can board U.S. Coast Guard vessels operating in Tonga waters. The rider agreement integrates well with existing security arrangements without placing additional strain on local law enforcement assets.

To increase the number of vessels able to identify and intercept illicit maritime actors, the parties could expand the agreement to include U.S. naval vessels, such as the agreement the U.S. signed with Fiji. Similarly, multilateral air patrol agreements could improve maritime domain awareness moving forward. The lack of aircraft available for patrols has created gaps in maritime surveillance that infrequent fly-overs, such as those conducted by New Zealand, France, the United States, and Australia over Tonga, via bilateral air patrol agreements cannot sufficiently address at their current levels.

Enhancing Information Sharing

In addition to patrol assets, information sharing mechanisms form an essential component of maritime security by allowing agencies, governments, and multilateral organizations to synthesize and assess security threats based on a holistic view of the maritime domain. Analysts can use the information collected from maritime patrols, human intelligence, and a variety of geospatial data-acquisition technologies to prioritize where to direct limited maritime assets. Information centers already exist within the South Pacific for gathering and disseminating data on maritime issue areas. The Transnational Crime Coordination Center, for instance, collects datasets on 13 South Pacific islands through the use of 19 Transnational Crime Units. The center uses the datasets to inform South Pacific island leaders on emerging threats, such as an increase in sex offenders traveling by sea to South Pacific islands for child sex exploitation. The region would, however, benefit from improving information-sharing networks on the national level, where lack of transparency hinders cooperation.

To improve the accuracy of information available at the regional level and in support of ongoing information sharing by island nations and local multilateral organizations, external stakeholders have proposed the creation of information fusion centers. Both Australia and the United States have mentioned the possibility of leading initiatives to create information fusion centers within the South Pacific region. While the involvement of both nations would be advantageous, increased coordination is necessary to avoid creating disparate systems. Australia’s previous contributions to maritime security in the South Pacific through initiatives like the Pacific Maritime Security Program, which have consistently provided law enforcement vessels and conducted aerial surveillance patrols for a dozen islands in the region, may make the country the more natural choice for leadership of future efforts in this area.

Building Security Assistance Capabilities: Acknowledging the Nexus Between Land and Sea

The porous nature of the divide between land and sea, especially in the island nations of the South Pacific, means that governments need to coordinate security operations across both domains. As underscored in the Stable Seas report, Violence at Sea: How Insurgents, Terrorists, and Other Extremists Exploit the Maritime Domain, an overemphasis on one domain can result in increased activity in the neglected domain as illicit actors attempt to exploit areas with lower levels of security. Conflict-consolidation, post-conflict development, and transnational criminal operations, especially in recent conflict areas like the Solomon Islands, Bougainville, and Fiji, warrant stronger security assistance capabilities within the South Pacific. A maritime security emphasis during these operations makes inciting and sustaining armed conflict difficult. The interception of two large shipments of small arms to Fiji prior to the coups illustrates how non-state actors can utilize the maritime domain to support terrestrial agendas.

Inter-governmental organizations within the region have taken steps to allow for South Pacific island-led peacekeeping initiatives. In 2000, the PIF released the Biketawa Declaration, which outlines the procedure for collective actions at the behest of a member state or when a crisis necessitates intervention. The document created a legal basis for the deployment of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, which included 14 PIF member states, and lasted from 2013 to 2017. Limited resources and infrastructure within PIF, however, means the organization would face logistical difficulties without the explicit support of larger member states like New Zealand and Australia. Increased funding for the organization could result in greater autonomy in decision-making by smaller member states, giving them the opportunity to exploit their nuanced understanding of the political and cultural milieu, and emphasize the importance of human security in the maritime domain.

Foreign entities could also support locally-led peacekeeping efforts by helping create and then lend expertise to a Pacific Islands Peace Operations Training Centre (PI-POTC). Similar to the Australian Defense Force Peace Operations Training Center, the center would create an opportunity for an exchange of information and training with national and international institutions to develop capacities in line with international standards. The center’s pacific island leadership would allow peacekeeping training to continue reflecting the region’s political, cultural, and security dynamics and emphasize the important role of maritime security to the South Pacific islands.

How Can Aid Programs Increase Coordination?

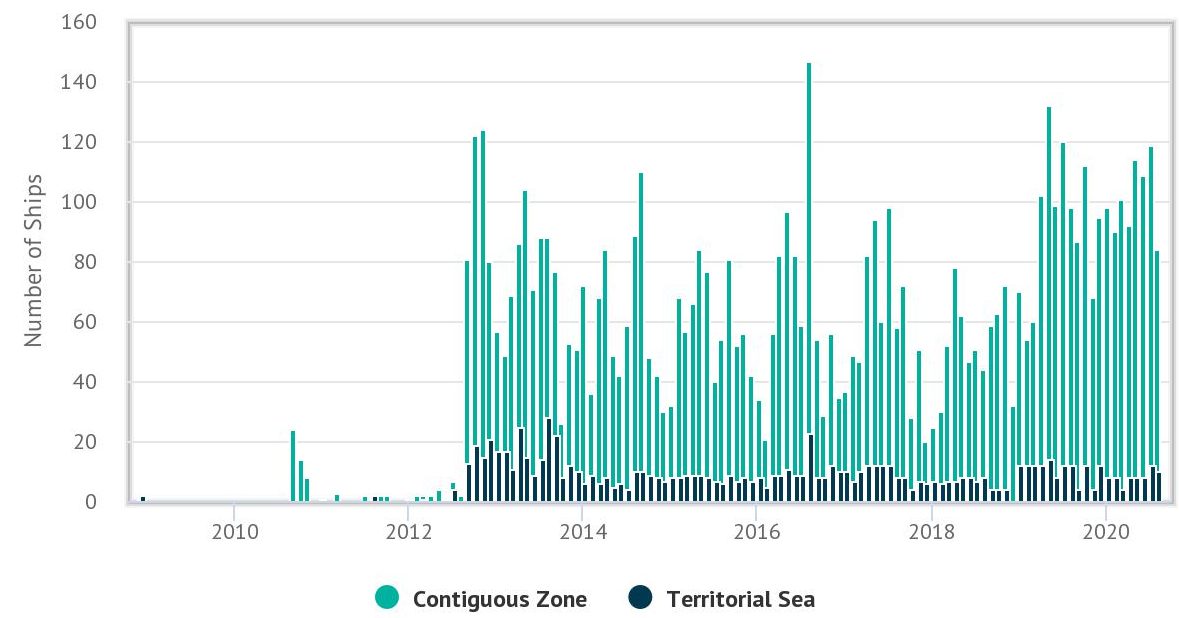

The multitude of foreign entities and programs providing funding, training, assets, and issue-specific expertise through maritime security capacity-building programs can create duplication of efforts and inefficiencies in implementation. Contention has arisen, for example, over discrepancies in aid provisions made by China in comparison to western states. China provides support without requiring any prerequisites for aid provision. Western nations, however, tend to require that host-countries first meet political, social, and security conditions before providing aid in order to encourage responsible aid allocation and implementation. The differences in viewpoint have been exacerbated by recent geopolitical tensions in regard to China’s growing sphere of influence in the South China Sea, East China Sea, and the Indian Ocean. The $90 million wharf funded by China in Luganville, Vanuatu has parallels to China providing $1.3 billion in funds to build a port in Hambantota, where Sri Lanka’s inability to repay the loans resulted in debt entrapment.

New Zealand’s successful coordination with China on water infrastructure projects in the Cook Islands demonstrate that nations can overcome the geopolitical and institutional differences to find mutually agreeable solutions. While trilateral approaches between western states, China, and South Pacific islands have a future, recent disputes arising from the water infrastructure project in Cook Island show parties still need to improve coordination. The creation of a multilateral forum similar to the UN Development Cooperation Forum could form a neutral setting to facilitate transparency between traditional western donors and emerging donors like China in any future maritime security capacity-building efforts.

Conclusion

Given the strong influence of the maritime space on the national economies and local communities within the South Pacific, the deleterious effects of non-traditional threats to human security in the maritime domain are of significant concern to the island nations. By further enhancing MDA, maritime law enforcement capacity, and security assistance capabilities, local South Pacific island governments and multilateral organizations can protect their maritime-based economies. To maximize impact, foreign entities should integrate aid programs into existing local maritime initiatives. Closely involving local agencies, national governments, and regional organizations in the development and implementation phase can reduce the potential for redundancies and incompatibilities with existing initiatives.

Michael van Ginkel works at One Earth Foundation’s Stable Seas program where he researches Indo-Pacific maritime security. His research and publication background focuses primarily on conflict resolution and prevention. Michael graduated with distinction from the University of Glasgow where he received his master’s degree in conflict studies.

Featured Image: Members of the Vanuatu Police Force examine a map during a tour of the USNS Sacagawea as a part of Exercise Koa Moana 17, off the coast of Vanuatu, Aug. 19, 2017. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by MCIPAC Combat Camera Lance Cpl. Juan C. Bustos)