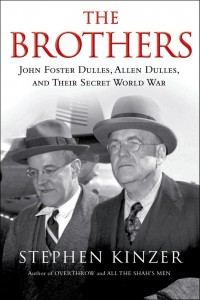

Back in March, I had the opportunity to listen to a panel at Brown University on civilian-military relations, titled, “In and Out of Uniform: Civilian Military Relations Reconsidered.” The panel was born from the provocative piece by James Fallows in The Atlantic magazine, titled, “The Tragedy of the American Military.” It was an interesting discussion. One of the highlights that day, at least for me, was walking away with a book. I happened to sit next to journalist and author Stephen Kinzer during a lunch that preceded the panel. We got to talking, and eventually he brought up his book The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and their Secret World War. Later that day he gave me a copy. A few weeks later I read it. It was a fascinating book on two men that, unknown to me, had a big impact on American foreign policy during the Cold War. Recently I had the chance to chat with Stephen about the Dulles brothers and their legacy in U.S. foreign affairs.

Stephen Kinzer, welcome. I enjoyed the opening anecdote of your book about the naming of the Dulles airport and how you “found” the bust of John Foster Dulles. How did that come about?

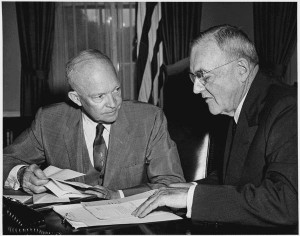

This is a fascinating story and there is actually a footnote that you probably don’t know. So as you say, I do start out my book with this anecdote about Dulles airport. So of course, John Foster Dulles was the secretary of state during the 1950s when his brother Allen was head of the CIA. The new airport being built outside of Washington D.C. was being named after John Foster Dulles. In 1962 there was a big ceremony at the airport. I watched a video on YouTube which showed when the airport was inaugurated. President Kennedy was there, former President Eisenhower was there, Allen Dulles was there. And a curtain was pulled back to reveal a bust of John Foster Dulles. The bust was placed in the center of the airport.

While I was writing this book I decided I want to go to the airport and find the bust. I wanted to commune with it in a sense; I wanted to see what it looked like. But I couldn’t find it. I asked around and nobody knew where the bust was. It’s a long story, but ultimately I found it in a closed conference room. And I used this story as a kind of a nice metaphor for how much we have forgotten John Foster Dulles. I repeated that story during my book tour. I probably gave 100 talks about this book over the last year or two and that was often the way it would start out. This story about how this guy was so famous and now how you can’t even find his bust. So that’s the story, but here’s the footnote.

Not long ago I got a phone call from one of my friends who said, “You are not going to believe this. I’m calling you from Dulles airport. The bust is back.” And sure enough, they’ve taken the bust out of the private conference room and put it back on public display. So first I wondered if this had something to do with the fact that I had pointed out what had happened with the bust. I thought I had achieved something great that showed the massive power of the press. But now I realize that it’s not so good because I have brought him out of the obscurity which into it had fallen, but without any context, so he is essentially being portrayed as a heroic figure. I am wondering whether I couldn’t set up a little booth next to the bust and sell copies of my book so people could understand who he really was.

Why the Dulles brothers? What interested you about them to write a book on those two men?

I am interested in the question of American intervention overseas. One thing I often ask myself is Why are Americans like this? Why do we do this? Why are we so eager to intervene in the affairs of other countries? I concluded that the story of the Dulles brothers and what they did in the 1950s would help explain some of that. The forces that created the Dulles brothers are the forces that created America. If you can understand those sources you can understand a good deal about this country. And they left us some important lessons that are still relevant. So I am presenting a biography here: this is the story of these two immensely powerful brothers who helped shape the world in the 1950s. But in the larger sense I am using the framework of biography to ask larger questions about the way the United States behaves in the world.

It seems like John Foster Dulles, and Allen Dulles to a certain extent, were very religious. And as I read your book, it appeared that their religious background colored their world view. Did it not?

They were brought up in a particular Calvinist religious tradition and came from a long line of clergymen and missionaries. They were taught, first of all, that the world was divided between good and evil and that there was one true religion, that all the other religions were wrong and evil. If you believe that about religions, it is a very short step to believing the same thing about world politics — that there is one political system that’s the right and good system for people to live under rather than all the other systems which are wrong and evil. In addition, they grew up with a strong admiration for the missionary idea, which tells you that a good Christian should not simply stay home and hope that good triumphs over evil, but now he has to go out and wage the fight on behalf of good. This is another religious precept that is easily transferable to the political realm. You begin to believe that it isn’t enough for us to enjoy the blessings of freedom at home. We need to go out into the world and liberate others who are not enjoying what we consider the blessings that they deserve.

While the brothers do share similar traits, they did have different temperaments. Is that correct?

It is quite a remarkable feature, their personalities. Politically and professionally they were identical. They saw the world the same way. They had grown up intimately, shared a worldview and hardly ever disagreed about anything. That was one reason it was so dangerous to the United States to have the two of them in power. They never felt the need to consult any experts other than the two

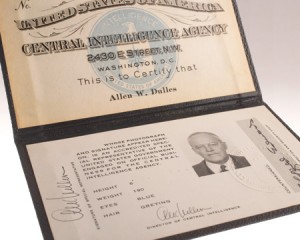

of them. So politically they were peas in a pod. In their private lives however, in their personalities, they were direct opposites. Foster Dulles was dour and gruff and socially inept. I have a whole page in my book about all the awkward things he would do. Even his friends didn’t like him. Allen Dulles, the CIA director, was just the opposite. He was a sparkling personality with an endless supply of stories. He had a wine cellar; he was a tennis player; he had a 100 mistresses; he was a wonderful addition to the Washington dinner scene.

Allen Dulles, as you say in your book, was intrigued with Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. Do you think this paved the way for him to become a spy. Is this something that he was incredibly intrigued with?

I think there was a kind of romantic fascination on the part of Allen Dulles in the idea of covert action. He read Kim when he was a young man and he kept it with him his whole life. It was on his bed table when he died. I would go on to another equally romanticized version of the espionage trade that Allen Dulles came to appreciate later in life. That was the novels of James Bond. Those novels have nothing to do with real life intelligence work. They show that the work of a single intrepid agent can change the course of history and that there are never any long term effects as soon as the bad people are done away with. This is a very dangerous mindset for intelligence agents to get into because the real world is not like that. At some point Allen Dulles even asked his tech division at the CIA to duplicate some of the gadgets that James Bond used. He was told that those were not realistic. It shows a little bit of the danger of mixing reality and fiction. I think Allen Dulles fell into that sometimes.

The Dulles family, specifically their grandfather and their uncle, had a lot to do with their path in life. I thought it was fascinating that John Watson Foster, their grandfather, is responsible for the concept of defense attachés in our embassies. Could you expound on that?

I mentioned a moment ago that one of the factors that shaped the Dulles brothers was their religious background. A second factor is the family background to which you refer. Their uncle was secretary of state — Robert Lansing — but their grandfather, John Watson, was also secretary of state. So as kids they grew up with these two remarkable relatives. John Watson Foster was a remarkable paragon of the American experience during the age of Manifest Destiny. He grew up on the frontier and made a business for himself, ingratiated himself to powerful men, rose through politics and became an ambassador, and then became secretary of state. Doing among other things, he modernized the state department and began the practice of systemic research into

foreign embassies and advances in foreign weaponry military tactics. He sent messages to all American legations asking them to send people to libraries and bookstores to look for anything new that was being developed in these fields. John Watson Foster was also the secretary of state who presided over the first American overthrow of a foreign government — that was Hawaii — in 1893. He would have later understood the role John Foster Dulles played, almost half a century later in overthrowing governments in Iran, Guatemala, and other places. I began to wonder if there wasn’t some genetic predisposition to regime change in the Dulles family.

The Dulles brothers seemed to jump back and forth between public service and the private sector — particularly back to the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell. Was this a trend throughout their lives?

Now you are putting your finger on what I think is the third most important factor in shaping the Dulles brothers. Religious belief was one, family and class background was the second, and certainly the third was the decades that the brothers spent working for the remarkable law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell in New York. This was not a law firm like any other. It had its speciality. Its speciality was helping big American companies pressure foreign governments into doing what they wanted. Virtually every large American multi-national corporation retained Sullivan & Cromwell. Every time those companies had trouble in some other country they would turn to Sullivan & Cromwell. Sullivan & Cromwell found ways to make offers to those countries that they couldn’t refuse. It means that the Dulles brothers understood the world from the perspective of their Wall Street clients. It also means that at an early age they became experienced in the technique of pressuring foreign governments. The skills that they learned at Sullivan & Cromwell would serve them well when they came into power in the 1950s.

Both men went to law school. Was the law just a stepping stone for those men in that age?

John Foster Dulles was the highest paid lawyer in America during the peak of his career. He was a masterful servant of the plutocracy, although he was not a plutocrat himself. I think their service in that world gave them a certain perspective about what should motivate American foreign policy. They saw a world in which a great force was arrayed against the United States. And they took this back to the experiences they had at the law firm and they felt that foreign governments were always seeking to use pressure on American companies as a way to pressure the United States. It was not possible for them to imagine that foreign governments would take steps that would be harmful to American companies. This was strictly out of reasons that came from domestic politics; not because they had been ordered to do so by the Kremlin or that it was some part of a broader geopolitical plot. So they came to office with a narrow vision that I do think came from their legal work.

Something that surprised me to learn was that John Foster Dulles was supportive of National Socialism in the early thirties.

John Foster Dulles was quite sympathetic to the Nazi party in the 1930s. He spent a lot of time in Germany. He was an admirer of Hitler in the 1930s. John Foster Dulles became the principal broker in the United States for German bonds that supported the municipalities and corporations. He also weaved the Krupp iron works company into an international nickel cartel that gave the Nazis access to nickel, which of course is important in warfare. He continued to visit Germany all the during the 1930s. His law firm closed its office in Germany but he was against it. So Foster Dulles did have a history of sympathy for the Nazis. I think part of the reason for that was he saw them as a bulwark against the Communists.

What is happening during the brothers during the 30s? When did they figure out that they would have to fight the Nazis? Did John Foster change his thinking?

In the mid-1930s Sullivan & Cromwell took a vote to close their Berlin office. As I said, Foster Dulles opposed that. But once the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939 it became impossible to paint them as peace lovers. And certainly after the American declaration of war everything became quite clear. It was after that declaration that Allen Dulles was named head of the OSS station out of Bern,

Switzerland. It was a very important post because it was one of the last remaining neutral outposts in Europe. Allen had a quite an adventure getting into Bern. He had a lot of fun times in Switzerland. It was his second tour there, he had been an intelligence officer in Bern during the First World War.

Let’s fast forward a little bit to the 1940s and 1950s. Tell us what operation Ajax was and please, if you could, tell us about Allen Dulles and John Foster Dulles roles in that operation.

When the Dulles brothers came into office in the early 1950s, Iran was establishing its democracy and had propelled this interesting leader — Mohammed Mossadegh — to the prime ministers job. Mossadegh had persuaded the Iranian parliament to vote for the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry. This industry had been previously owned by one British company which was in turn owned principally by the British government. So the nationalization of Iranian oil was quite the topic at the time the Dulles brothers came into power. And they had relations with Iran in the years before that. The Dulles brothers, when in Sullivan & Cromwell, represented the bank for the British oil company that operated in Iran, and that bank lost its interest. So the Dulles brothers came into office with a grudge against Mossadegh. Mossadegh had also helped kill a big development for American engineering firms that Allen Dulles had helped broker. His threats to the international oil cartel was thought of as dangerous, not just to oil but to all international and multinational businesses because they challenged the concept that rich countries are entitled to resources from poor countries at the price that they want to pay. So once in power, the Dulles brothers began immediately plotting against Mossadegh, and he was overthrown eight months later and Iran never recovered from it.

Communism was also a driving concern for the Dulles brothers at this time as well, correct?

Certainly the way the Dulles brothers saw the world was a great confrontation between Communism and capitalism. That would have been the way most Americans saw the world. Most of our major institutions saw the world through that prism. The Dulles brothers believed that everything that happened in the world was in some way related to this conflict. People in other parts of the world saw the global situation differently. In much of Asia and Africa and Latin America the world looked like it was divided in a different way. It seemed to be divided between dozens of new nations that were trying to find their place in a turbulent world on the one hand. And then there were the old traditional ruling powers that were trying to keep them back and prevent their nationalism from flowering into projects of development at home and neutralism abroad. So the world looked very clear to the Dulles brothers, and everything that happened in it seemed to be part of the Cold War struggle. That’s why they found so many enemies in the world; they were loose in their interpretation what constituted an enemy or hostile activity.

They didn’t necessarily agree with some of the other big names back then that also didn’t like Communism — John Foster Dulles was not a big fan of George Kennan, was he?

No, as a matter of fact it was Dulles who forced George Kennan out of the state department. Kennan didn’t see the world in as clear black and white terms as Dulles did. And I think the state department was not big enough for both of them. It was clear that Dulles could not run the state department listening to Kennan. And Kennan didn’t want to be there giving advice to someone who saw the world so differently.

The famous theologian and philosopher Reinhold Niebuhr also disagreed with Dulles, didn’t he?

Niebuhr warned against nations becoming too arrogant. He felt if the United States was faced with extinction as a country it wouldn’t be from a foreign threat; it would be from our own hubris and self-destructive impulses. That was not the way John Foster Dulles saw the world. So they were critics of each others visions.

Is it true that the birth of the U2 program started at a dinner party?

Allen Dulles was having a dinner with some scientists and they spoke about some advances in high-altitude photography. This led him to call a few people into his office and ultimately produced what became the U2 project. That was particularly important in those days. One reason the Cold War became so intense was our absolute ignorance on what was going on inside the Soviet Union. Because we were allies during WWII we hadn’t really concentrated on building intelligence networks inside the Soviet Union. So when the war was over we were really shut out; it was a denied area to Americans. One of the very first flights that the U2 took brought back information that we had greatly overestimated the number of fighter jets that the Soviets had. This kind of information came back repeatedly from U2 flights. That did play a role, I think, in calming some overblown fears.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=1-CeBS2EFWM%3Frel%3D0%26autoplay%3D1%26wmode%3Dopaque

Let me close with one more question. What do you think the Dulles brothers biggest effect was on US foreign policy? What is their legacy look like today?

The Dulles brothers approach to the world did not work out well for the United States. Rather than confront that fact and see what lessons we can draw from that experience, we find it easier to forget about them and move on. That’s one reason why these brothers who were so famous in the 1950s are now effectively forgotten. They did however leave some very important legacies. One is that they were strongly opposed to negotiation with our enemies. John Foster Dulles always opposed summit meetings between the U.S. President and leaders of the Soviet Union or Communist China. Nations should first show some sympathy toward us or be friendly toward us or we should not negotiate with them. That tendency is still strong in the United States today.

A second tendency that they felt was an absolute lack of understanding of the nature of Third World nationalism. They saw every assertion of nationalism by countries in other parts of the world as defiant to the United States. They wanted countries to be subservient to the United States. They couldn’t understand the desire for countries to make their own choices, even if they were not good ones.

The finally legacy they left us is that they had no idea of what today we would call “blowback.” It never occurred to them that their operations would have such long term consequences. Perhaps, like James Bond, they kept this idea that you go out in the world and you violently intervene in the political process of another country and then everything will go back to normal, with no serious effect. It never occurred to them that by destroying democracy in Iran it would send that country into a spiral of dictatorship and religious rule that would last for generations. When they overthrew the democratic government of Guatemala that a genocidal civil war would break out in which hundreds of thousands of people would be killed. When they decided to pursue Ho Chi Minh after the British and French decided he could not be defeated, it never occurred to them that it could trigger a war that cost so much pain and horror for Vietnam and the United States. That’s a good lesson for us to learn from them — I think all three of those are. Never negotiate with your enemies. Don’t recognize the nationalist sentiments of people of other countries. And delude yourself into believing that there will never be any long term effects to foreign intervention. Those would be the three lessons from the Dulles brothers that we would be wise to learn from.

Thank you very much Stephen, what’s next for you?

I am working on a book about the period when the United States first became involved in taking overseas territories, which was around 1898. Maybe we can get together for another chat then.

That sounds great. Thank you Stephen Kinzer, it was a pleasure talking with you.

Thank you.

Stephen Kinzer is an award-winning foreign correspondent whose articles and books have led the Washington Post to place him “among the best in popular foreign policy storytelling.” Kinzer spent more than 20 years working for the New York Times, most of it as a foreign correspondent. He was the Times bureau chief in Nicaragua during the 1980s, and in Germany during the early 1990s. In 1996 he was named chief of the newly opened Times bureau in Istanbul. Later he was appointed national culture correspondent, based in Chicago.Since leaving the Times, Kinzer has taught journalism, political science, and international relations at Northwestern University and Boston University. He has written books about Central America, Rwanda, Turkey, and Iran, as well as others that trace the history of American foreign policy. He contributes to the New York Review of Books and writes a world affairs column for the Boston Globe. Currently, he is a Fellow at the Watson Institute of International Studies at Brown University.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is a naval intelligence officer and the book review editor for the Center for International Maritime Security. He is a recent graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI. Those interested in reviewing books for CIMSEC can contact LCDR Nelson at [email protected] The views expressed in this paper are those of only the authors and do not express the official views of the US Navy, the DoD or any agency of the US Government.