A version of this piece was originally featured by the U.S. Naval War College’s Stockton Center for International Law under the title, “Rudderless and Adrift: States’ Unwarranted Timidity Respecting

Stateless Vessels.”

By Andrew Norris

Despite the fact that the oceans are extensively used for contraband smuggling, including narcotics, there is not a correspondingly robust legal regime at sea for contending with this problem. Except for a very limited coastal State entitlement to ‘prevent’ customs offenses (including narcotic trafficking) in the contiguous zone, the flag State alone is entitled to exercise prescriptive, enforcement and adjudicative jurisdiction over its vessels and those aboard them for such offenses in all waters outside the sovereign waters (i.e. territorial sea and inward) of another State. UNCLOS Article 108 merely exhorts States to cooperate in combatting narcotics trafficking at sea, and treaties such as the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (hereinafter Vienna Drug Convention), the Jeddah Amendment to the Djibouti Code of Conduct, and Caribbean bilateral agreements typically just provide fidelity on how such cooperation should occur. The Right of Visit (ROV) per UNCLOS Article 110 is a useful tool, but is limited to a determination of vessel nationality only – jurisdiction over a vessel for any narcotics trafficking offenses remains the sole province of the flag State in the case of a properly flagged vessel.

Specific to the issue of law enforcement jurisdiction at sea, Article 4 of the Vienna Drug Convention requires Parties to take measures to establish jurisdiction over violations of their narcotics criminal laws occurring in their territory or on board a vessel flying their flag. It also suggests that Parties take measures (such as obtaining flag State consent) to establish jurisdiction over vessels flying the flag of another State. What Article 4 does not touch on is the ability of States to establish and exercise jurisdiction over vessels without nationality or those assimilated to vessels without nationality under international law (collectively referred to hereinafter for ease of reference as stateless vessels).

Recognizing that the inability to exert maritime law enforcement jurisdiction over stateless vessels creates a significant gap in the overall global effort to combat narcotics trafficking at sea, some nations have extended their jurisdictional reach more robustly over such vessels. For example, Article 3 (Jurisdiction) of the 1995 Council of Europe’s ‘Agreement on Illicit Traffic by Sea,’ implementing Article 17 of the Vienna Drug Convention, requires a State Party to ‘take such measures as may be necessary to establish its jurisdiction over the relevant offences committed on board a vessel which is without nationality, or which is assimilated to a vessel without nationality under international law.’ Similarly, the U.S. fulfilled its obligations under Article 4 of the Vienna Drug Convention by expanding (and routinely exercising) its jurisdictional reach over stateless vessels in its principal maritime narcotics smuggling law, the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act (MDLEA).1

Unfortunately, such robust jurisdictional postures with respect to stateless vessels engaged in narcotics trafficking at sea are more the exception than the norm. It is not entirely clear whether the failure by many States to more aggressively assert jurisdiction over stateless vessels is the product of legislative lethargy (it requires affirmative action by a State to decide on, adopt, and publicize an enhanced jurisdictional posture) or a mistaken belief that a more robust posture is forbidden by or contrary to international law. As demonstrated below, this second basis is legally incorrect, and to the extent nations are failing to adopt a more robust jurisdictional posture toward stateless vessels based on it, they are voluntarily and needlessly restraining themselves to the ultimate benefit of maritime criminals.

Neither Conventional law, customary international law, nor decisions of international tribunals prevent a more robust exercise of jurisdiction over stateless vessels. The Conventional (or treaty) law of nations, as embodied in UNCLOS, does not answer the question of the extent of jurisdiction States may exercise over Stateless vessels. All it says, in Article 92(2), is that ‘[a] ship which sails under the flags of two or more States, using them according to convenience, may not claim any of the nationalities in question with respect to any other State, and may be assimilated to a ship without nationality.’ This provision is unsatisfactory in several ways. First, it only relates to one of several means by which a vessel can be considered stateless for jurisdictional purposes – it is entirely silent as to other means (e.g. true statelessness, failure to make a claim of nationality). Also, it provides no guidance at all on the ultimate issue, which is the jurisdictional consequence of a vessel being ‘assimilated to a ship without nationality.’

Equally unsatisfying in terms of establishing or defining the international law related to jurisdiction over stateless vessels is State practice. Customary international law results from a general and consistent practice of States that they follow from a sense of legal obligation. A doctrine or principle that rises to the level of customary international law is binding on States to the same extent as treaty law. Unfortunately, as comprehensively addressed in Chapter 15 of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s Maritime Crime: A Manual for Criminal Justice Practitioners (3rd ed.), ‘there is no settled answer’ in State practice to the scope of jurisdiction that a boarding State may assert over a stateless vessel. According to the Manual, ‘[s]ome States may determine that they can, in effect, treat the vessel as one of the boarding State’s own nationality’ and as a consequence ‘may claim that it can assert the same jurisdiction over the suspect vessel as it could assert over a vessel of its own nationality.’ However, ‘[o]ther States may be of the view that the statelessness as such of the vessel does not suffice in order to assert jurisdiction over the vessel and the persons on board. Accordingly, they would assert jurisdiction only if there is some other jurisdictional link with the activity of the vessel or the persons concerned’ – such as, for example, an assault on a boarding officer during a ROV boarding. Which viewpoint is correct is not the point here. Rather, the mere fact that this divergence in practice exists, by definition, means there is no settled customary international law that settles the issue.

The consequence of international conventional law that remains largely silent on the issue of the jurisdictional effect of vessel statelessness, and State practice falling into one of two divergent camps, is there is no definitive ‘rule of international law’ on the issue of stateless vessel jurisdiction. In such a case, the Lotus principle (deriving from Case of the S.S. “Lotus” (Fr. v. Turk.), 1927 P.C.I.J. (Ser. A) No. 10), which is a fundamental principle of international law, stands for the proposition that ‘[the absence of a definitive rule] leaves [States] a wide measure of discretion, which is only limited in certain cases by prohibitive rules. As regards other cases, every State remains free to adopt the principles which it regards as best and most suitable.’

In other words, the focus in the absence of generally accepted law is not on whether international law permits a certain action, but rather whether is prohibits such an action. In the absence of such a prohibition, ‘all that can be required of a State is that it should not overstep the limits which international law places upon its jurisdiction; within these limits, its title to exercise jurisdiction rests in its sovereignty.’

In 2024, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in United States v. Marin (No.22-50154, decided on January 17, 2024) applied the Lotus principle to uphold a provision of the MDLEA that permits the U.S. to assert prescriptive, enforcement, and adjudicative jurisdiction on the basis of statelessness over ‘a vessel aboard which the master or individual in charge makes a claim of registry and for which the claimed nation of registry does not affirmatively and unequivocally assert that the vessel is of its nationality.’ According to the court, ‘[d]efendants do not identify a rule of international law requiring an oral claim to nationality be rebuttable only by a denial by the claimed flag state. In fact, such a rule could lead to the untenable result that neither the boarding state nor the claimed flag state have jurisdiction over a vessel so long as the claimed flag state does not confirm or deny nationality —undermining international law’s role of facilitating the “achievement of common aims.”’ Since, according to the Marin court, no international law prohibits the specific practice at issue, the U.S.’s exercise of jurisdiction on this basis ‘is not contrary to international law under the Lotus principle’ and does not ‘overstep the limits which international law places upon . . . jurisdiction.2

A U.S. court ruling is most certainly not determinative on the issue outside the United States. However, that ruling squarely addressed the international legality of perhaps the most aggressive of the situations in the MDLEA that permits the U.S to exercise jurisdiction over a vessel on the basis of statelessness, and determined that there was no rule of international law forbidding such an exercise in that situation. Assuming this conclusion is correct, application of the Lotus principle leads to a conclusion that the U.S. or any other nation choosing to adopt this particular approach to stateless vessel jurisdiction is free to do so as an exercise of State sovereignty.

The same conclusion would apply to any other approach not specifically prohibited by international law. In fact, it can be argued that in view of the invitation, if not mandate, on States to expand their jurisdictional reach as a central component of the global scheme to cooperatively address the scourge of narcotics trafficking at sea, the failure by States to avail themselves of mechanisms not prohibited to them by international law is a self-inflicted infirmity that weakens the global commitment to good order at sea and unnecessarily cedes legal ‘space’ at sea to would-be traffickers and other purveyors of maritime disorder.

The bottom line is that States should clarify the extent and parameters of their jurisdiction over stateless vessels in their domestic laws. In doing so, they should join the States that, according to the UNODC, ‘determine that they can, in effect, treat the vessel as one of the boarding State’s own nationality’ and as a consequence ‘may claim that it can assert the same jurisdiction over the suspect vessel as it could assert over a vessel of its own nationality.’ There is no legal bar to them doing so, and failure to do so merely weakens their own maritime law enforcement power and the overall global scheme to address disorders at sea. And finally, though the focus of this analysis is on narcotics trafficking, that is merely for illustrative purposes. There is no reason whatsoever that nations could not similarly extend their jurisdictional reach over stateless vessels for any other types of maritime crimes or disorders, subject to any other legal limitations that might exist.3

Andrew Norris, J.D., is a retired U.S. Coast Guard captain who currently works as a legal and regulatory consultant through his business, Tradewind Maritime Services Inc. In 2024, he has supported the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in their maritime capacity building programs in the Pacific Ocean and Indian Oceans East regions. He also supports U.S. Defense Support of Civilian Agencies (DSCA) capacity building programs in partner nations. He is a founder of the Maritime Security and Governance Staff Course at the U.S. Naval War College, a resident 5-month course for international officers focused on maritime activities and missions short of war. His principal area of recent focus is on fostering collaboration and system improvements by judges, prosecutors, and enforcers to better achieve a successful ‘legal finish’ in maritime law enforcement cases.

References

1 Title 46 U.S. Code Chapter 705

2 There have been some international court rulings that call into question the continued vitality of the Lotus principle in the jurisdictional context. However, those cases related to jurisdiction over universal crimes (such as war crimes or piracy), which, being international crimes, cannot by definition be the subject of differential state jurisdictional interpretations. That is not so with respect to non-universal crimes like narcotics smuggling; the 1988 Vienna Convention, for example, acknowledges the competency of States to craft criminal prohibitions and their jurisdictional reach, even as it provides guidelines on the types of criminal activities such laws should address. It is the author’s view – not to mention that of the U.S. Ninth Circuit – that the Lotus principle, rooted as it is in State sovereignty, is alive and well in the context of jurisdiction over non-universal crimes, including narcotics enforcement.

3 For example, the U.S. adopts the MDLEA’s jurisdictional scheme over stateless vessels in its principal fisheries enforcement law. See 16 U.S.C. 1802(49). This is in accord with exhortations by, e.g., the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission or the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) that nations ‘take all necessary measures, including enacting domestic legislation if appropriate, to prevent vessels without nationality from undermining conservation and management measures’ adopted to conserve and protect covered fish stocks. Conservation and Management Measure 2009-09, WCPFC.

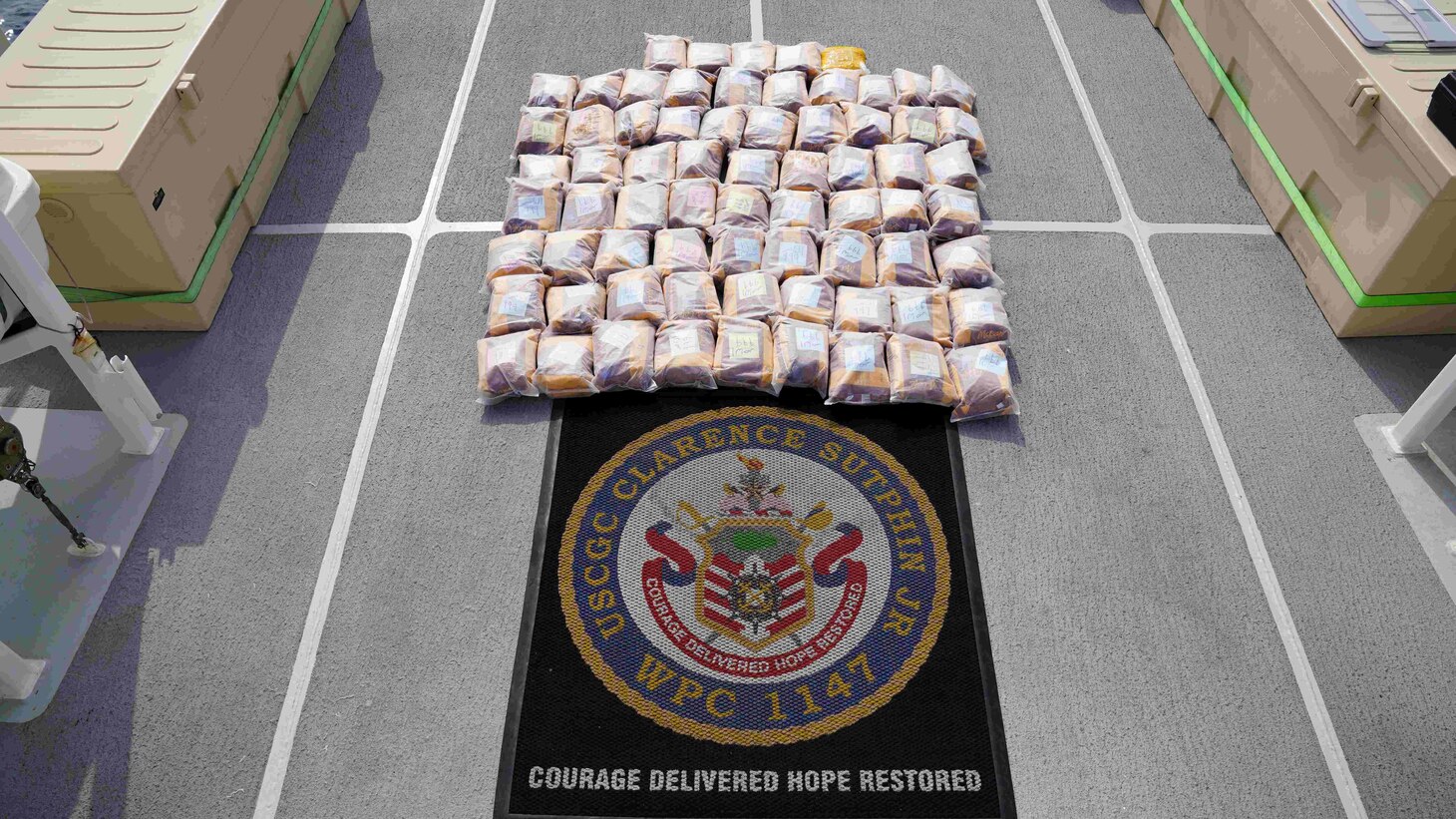

Featured Image: Gulf of Oman (Aug. 30, 2022) Bags of illegal narcotics sit on the deck of a fishing vessel interdicted by U.S. Coast Guard fast response cutter USCGC Glen Harris (WPC 1144) in the Gulf of Oman. (U.S. Coast Guard photo)