By Michael Paul and Göran Swistek

Introduction

With the Indo-Pacific Guidelines published in August 2020, the German government has taken a clear position for a geographical area that is characterized by the multidimensional competition between the West, led by the United States, and China. The Indo-Pacific region is rightly perceived as the trade and economic engine of a globally interconnected and mutually interdependent market. In particular, the security policy aspects outlined in these recent guidelines, along with Germany’s interests in the region and some prospective measures to support these interests have fueled high expectations amongst partners and Indo-Pacific Rim nations for a visible and strong German commitment.

Individual German government representatives have presented the deployment of the frigate BAYERN in the second half of 2021 as a first performance test of Germany’s positioning. As the planning for the frigate’s deployment gains concrete shape, the high degree of caution exercised by the German government in implementing the guidelines is becoming manifest. The German government is trying to avoid taking a clear position in the security policy competition with China. Irrespective of the claims formulated in the Guidelines, Berlin also seems to play its foreign policy feel-good role as mediator and balancer of the most diverse poles in the Indo-Pacific rather than advocate a rules-based international order. German partners in the region increasingly perceive this gap with justifiable criticism.

The Security Policy aspirations of the German Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific

The publication of the Indo-Pacific Guidelines by the German Federal Government in August 2020 has generated a great deal of attention among many partners in the Asian and South-East Asian region. For some, this is associated with the perception and hope that Germany will show more presence in line with its economic importance as a ‘global player,’ and will make a greater contribution to maintain the regional order and stabilize the region.1 The Indo-Pacific – as an area of profound geostrategic, political, and economic interests – has become the focus of public debate and political strategy papers, especially within the last decade.

The multidimensional competition between China and Indo-Pacific Rim nations has spurred this interest. The competition has an economic, technological, systemic and, not to be neglected, a security policy dimension. Owing to the region’s numerous security challenges, Germany has proceeded with great caution over the recent years. Individual measures have mainly been directed at supporting and training local police forces and other civilian security organizations, or contributing to reconstruction after humanitarian and environmental disasters. Apart from providing humanitarian aid after the tsunami in Banda Aceh (2004/2005) and, most recently, individual contributions to Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Atalanta off the Horn of Africa, the German armed forces have not been present in the region for the last two decades. Yet, this Indo-Pacific region, with all its challenges, is of particular geostrategic importance for many nations – including for Germany.

This predominantly maritime region is one of the largest economic hubs and is home to the largest share of global maritime trade by far. The South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait sit at the center of the Indo-Pacific geography – both cartographically and economically – at the transition from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean. Almost one third of the international trade in goods is shipped2 through these straits every year. These trade flows are not only indispensable prerequisites for a functioning and flourishing global economy, but they can also pose a threat to the maritime environment, the security of coasts as well as port cities and their populations in the event of a disruption or disaster at sea. Moreover, access to the sea and its resources – including fossil deposits (oil and gas), minerals, and fish – is increasingly contested. Finally, there is a causal relationship between trade and prosperity; trade requires secure and stable trade routes to be fully developed. Prosperity is hence directly dependent on security. Germany’s way of life and economic prosperity are largely dependent on secure sea routes, and this is particularly true of the Indo-Pacific. The share of Germany’s trade in goods with the countries of the Indo-Pacific, measured in terms of total volume, amounts to about 20 per cent.3

The potential threats in the region are multi-layered: In addition to the often overarching strategic, economic, and systemic rivalry between the US and China, there are three nuclear powers in the Indo-Pacific (China, India, Pakistan) plus North Korea as a de-facto nuclear power whose intentions are especially difficult to calculate. This fragile constellation is made even more precarious by unresolved border disputes, internal and interstate conflicts, regionally and globally active terrorist organizations, piracy, organized crime, and the effects of natural disasters and migration movements. The latter aspects in particular, which tend to be summed up as non-traditional security threats, are high on the security policy agenda of the Indo-Pacific Rim nations.

The broad spectrum of security threats is in obvious contradiction with the importance of the Indo-Pacific for global flows of goods. In response to this security situation and as a perceptible implementation of the guidelines, the Federal Government intends to expand German engagement with the region in the future. It intends to intensify security and defense cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, depending on the context, with individual states or organizations such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and with actors who also have interests in the region. This can take place both unilaterally and within the framework of the EU, NATO, or the United Nations (UN).

In terms of content, Germany wants to be engaged in the following areas: Arms control, non-proliferation, cyber security, humanitarian and disaster relief, combating piracy and terrorism, conflict management and prevention, including the preservation of the rule-based order and the enforcement of international legal norms such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The instruments that the German government would like to use to these ends range from expanding and deepening cooperation in the region, to civilian and military diplomacy, to military presence in the context of exercises or other forms of on-site presence.

The BAYERN frigate as a symbol of the operationalization of the guidelines

For almost two years now, the German Navy has been planning to send a ship into the Indo-Pacific region. The deployment of the frigate HAMBURG planned for 2020 had to be cancelled at short notice in favor of the German contribution to the EU-led Operation IRINI off the coast of Libya. In her first policy guideline speech as Minister of Defense on November 7, 2019, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer formulated the associated intent that the Federal Republic would like to set an example vis-à-vis its partners, Germany cannot simply stand at the sidelines and watch but rather intends to contribute to the protection of the international order4. At the same time, the participation of German forces and units in the EU’s Operation Atalanta off of the Horn of Africa was only sporadically exercised by maritime patrols due to their maintenance availability. The navy has now temporarily suspended this deployment with units in the operation and will also withdraw its supporting logistical presence from Djibouti as of May 2021. The mandate for this operation has been extended by the German Parliament for the time being, but the navy has no units available for a permanent presence. Despite Djibouti’s pivotal geostrategic location, situated between the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean, at the gateway to Africa, the Indo-Pacific region, and the Arabian Peninsula, the location no longer be available for use as a possible logistics and base in support of regional developments. A temporary participation remains possible when German warships pass through this maritime region.

In her second policy guideline speech a year later, on 17 November 2020, the Defense Minister held out the prospect of sending a frigate in 2021 and linked its deployment directly to the requirements of the recently issued Indo-Pacific Guidelines: “We will fly the flag for our values, interests and partners.”5 At the beginning of March 2021, the Federal Foreign Office and the Federal Ministry of Defense then published concrete details on the upcoming tour of the frigate BAYERN. Starting in August, the frigate is scheduled to embark on a six-month journey, conducting more than a dozen official port visits between the Horn of Africa, Australia and Japan in the Indo-Pacific. In line with the guidelines for the Indo-Pacific, the task for the ship is initially to show presence in the region and deepen diplomatic relations, including official receptions on board. The German Defense Minister therefore formulates the mission of the frigate BAYERN primarily as a symbol that will show the German solidarity and interest in the region6. In addition, various exercises and drills with naval units of the host states, e.g. in Japan, as well as a short-term participation in Operation Atalanta are planned. The functional cause of the German deployment is to highlight the cooperation with the democracies in the region and to prove the German engagement in the security dialogues on the ground.7 The operational culmination of the tour is a three-week participation in the UN sanctions measures against North Korea. In this respect, the deployment of the frigate fulfils a mission that can be directly derived from the guidelines.

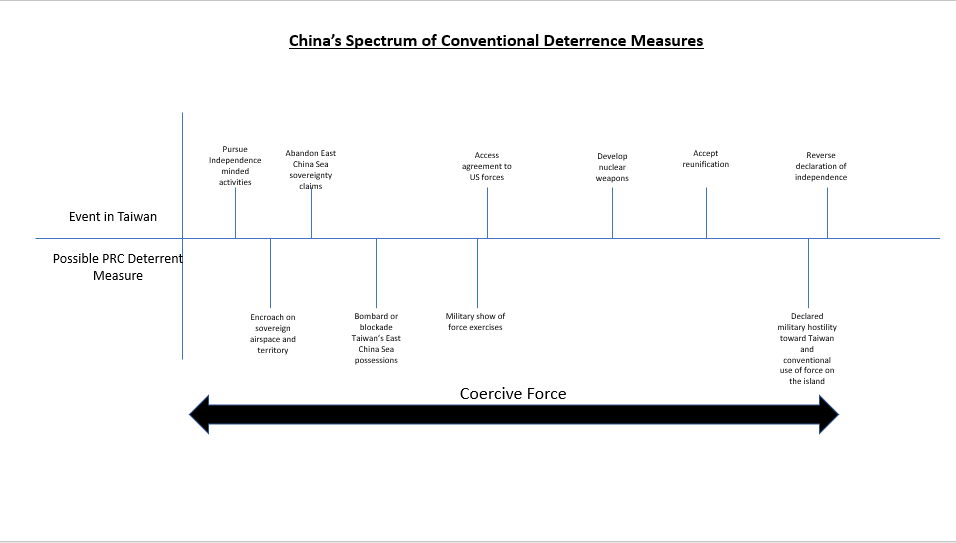

In contrast, the German government and the Armed Forces are much more attentive in their relations with China. Beijing’s behavior towards regional neighbors is not in line with the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Beijing is making disputed territorial claims to the Japanese-administered Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea and, beyond that, to most of the South China Sea – with the claimed territory also including the sovereign Republic of Taiwan. The International Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled on 12 July 2016 that Beijing’s claims did not comply with the Law of the Sea Convention and were therefore invalid.8

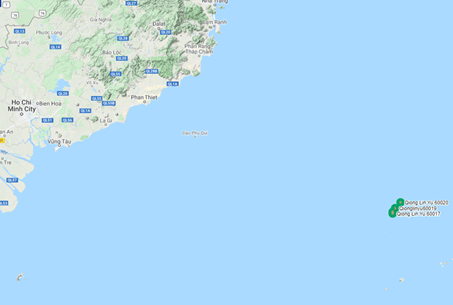

Nevertheless, the Ministry of Defense avoids conflict-prone sea areas when planning the details and route of the German warship. The frigate BAYERN will therefore not sail through the Taiwan Strait, but will bypass Taiwan on a longer route to the east. Similarly, in the South and East China Seas, the territories claimed by the People’s Republic of China will be bypassed and the frigate will move along the main international traffic and trade routes. Based on the time and distance factors for the tour of the German Warship, there will also be no interaction with the UK led carrier strike group assembled around the HMS Queen Elizabeth. The carrier strike group will start its deployment to the Indo-Pacific in May 2021 and intends to sail as far as to the Japanese Islands as well. Like the German frigate, it will bypass the Taiwan Strait. But unlike the German plans for its warship, the carrier strike group with its Dutch, US, and temporary Australian participating9 units is planning to conduct a Freedom of Navigation transit through the South Chinese Sea.10

Conclusion: Disappointed expectations

The presence of the BAYERN frigate is a first visible symbol of German interests in the Indo-Pacific, but it does not support the freedom of navigation called for in the Indo-Pacific Guidelines and its underpinning in international law through appropriate navigation in these free and open international sea lanes. It was precisely this contribution to international law and regional order that some Pacific Rim nations states had hoped for from Germany as a prominent representative of the EU canon of values.11 This made governments in the region all the more surprised about Germany’s announcement that it would also conduct a port call in China as part of the tour. On completion of its participation at the UN sanctions measures against North Korea the frigate BAYERN will sail through the East China Sea and conduct an official diplomatic port visit to Shanghai.

Since the initial announcement of the details for the deployment of the frigate BAYERN in March 2021, the German Minister of Defense repeatedly stated that the Freedom of Navigation aspect and the embedding in multilateral cooperation are key elements of this journey.12 The lack of cooperation with the UK-led carrier strike group invites speculation: Was it ignored or neglected for a certain reason, or simply missed in the planning process? Based on the publicly available information and announcements of the official German government agencies, the details of the tour have never been purposely altered since its publication to avoid any interaction with ships around the HMS Queen Elizabeth, as recently stated by some analysts.13 The more likely possibility is that the German Ministry of Defense never even considered any cooperation with the carrier strike group from the beginning, as such a combined naval force would send too strong signal for the German appearance in the Indo-Pacific.

Germany likes to present itself as a global player in foreign economic policy, but in foreign and security policy it hides behind limited capabilities as a middle power. This neither helps its partners in the Indo-Pacific, nor does it correspond to the often declared willingness to assume more responsibility. The BAYERN deployment plots a steady and cautious course to continued German reluctance.

Dr. Michael Paul is a Senior Fellow and Commander Goeran Swistek is a Visiting Fellow in the International Security Division of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

Endnotes

1. The Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi expressed his expectations during the virtual Asia tour of the German Defense Minister in autumn and winter 2020 in a round of talks on 17 December 2020, hosted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation. See, among others, Ryall, Julian, Japan calls on Germany to send warship to East Asia, Deutsche Welle, 18 December 2020, on the Internet at: https://www.dw.com/en/japan-germany-china-defense-challenges/a-55985940, last viewed: 03.05.2021.

2. The data was taken from the publications of the China Power Project by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. On the Internet at: https://chinapower.csis.org/much-trade-transits-south-china-sea/. Last viewed: 03.05.2021.

3. The Federal Government/Foreign Office: Guidelines on the Indo-Pacific. Available online at https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2380500/33f978a9d4f511942c241eb4602086c1/200901-indo-pazifik-leitlinien–1–data.pdf, last viewed: 13.01.2021.

4. Kramp-Karrenbauer, Annegret, First Policy Address by the Minister of Defense: https://www.bmvg.de/de/aktuelles/rede-der-ministerin-an-der-universitaet-der-bundeswehr-muenchen-146670, last viewed: 03.05.2021.

5. Kramp-Karrenbauer, Annegret, Second Policy Address by the Minister of Defense, Translation into English by the Authors, https://www.bmvg.de/de/aktuelles/zweite-grundsatzrede-verteidigungsministerin-akk-4482110, last viewed: 03.05.2021.

6. Internationale Politik, Interview with Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Das Deutschland führen soll, macht viele Angst, in: Internationale Politik, 28 April 2021, on the Internet: https://internationalepolitik.de/de/dass-deutschland-fuehren-soll-macht-vielen-angst, last viewed: 03.05.2021.

7. Ibid.

8. Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), PCA Case Nº 2013-19 in the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration before an Arbitral Tribunal Constituted under Annex VII to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea between The Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China. Award, 12.7.2016.

9. Tillett, Andrew, Australian navy to join UK carrier in regional show of strength, in: Australian Financial Review, 11. Feb 2021, in the internet: https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/australian-navy-to-join-uk-carrier-in-regional-show-of-strength-20210210-p57150, last viewed: 06.05.2021.

10. UK Defence Journal, British Carrier Strike Group to sail through South China Sea, in the internet: https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/british-carrier-strike-group-to-sail-through-south-china-sea/, last viewed: 06.05.2021.

11. Cf. Michael Paul, “Europe and the South China Sea: challenges, constraints and options”, in: Sebastian Biba and Reinhard Wolf (eds.), Europe in an Era of Growing Sino-American Competition. Coping with an Unstable Triangle, London and New York: Routledge, 2021, pp. 92-106.

12. See also Interview with the German Minister of Defense, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, in the internet: https://www.bmvg.de/de/aktuelles/verteidigungsministerin-akk-interview-multilateralismus-5049504, last viewed: 06.05.2021.

13. Kundnani, Hans & Tsuruoka, Michito, Germany’s Indo-Pacific frigate may send unclear message, in the internet: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/05/germanys-indo-pacific-frigate-may-send-unclear-message, last viewed: 06.05.2021.

Featured Image: The German naval ship BAYERN sets course for the Horn of Africa in 2011. The BAYERN led the European task force for the anti-pirate operation “Atalanta” for four months. Photo: Deutsche Presse-Agentur (DPA) 07/18/2011