By Peter Layton

As competition with China deepens, the nation’s use of gray zone techniques is becoming of increasing importance and interest. China has been using this approach for many years in the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and the India/China border, to name some prominent examples. Understanding the history behind these is important, but equally so is where China’s gray zone stratagems may be heading. In this, we live in the future, not the past. Understanding the direction towards which Chinese gray zone activities may evolve could give early warning about China’s likely next steps. Suitable responses could then be considered and implemented in a measured manner, without the time pressures induced by a sudden, unexpected crisis.

This article discusses three forward-leaning aspects: long-term trends, wild cards, and the shape of China’s future gray zone actions. Considered together, these outline future Chinese gray zone possibilities at the strategic and tactical levels, helping avoid potentially nasty surprises. Gray zone as used here builds on Michael Mazarr’s seminal work. Crucially, gray zone techniques are distinct from hybrid warfare. Gray zone techniques do not involve deliberate armed violence; hybrid warfare does, as defined in Frank Hoffman’s influential examinations. In recent years, China has doubled down on gray zone activities while Russia remains attracted to hybrid warfare. Neither the activities nor the countries should be conflated.

This article further focusses on China’s periphery, not globally. Using cyber, China can extend its gray zone activities worldwide, but looking in peripheral areas allows a broader, all-domain discussion. A deeper examination of China’s gray zone activities in the periphery is given in my China’s Enduring Grey Zone Challenge recently published by the Royal Australian Air Force’s Air and Space Power Centre.

Potential Evolutionary Paths

China has been using gray zone techniques for more than a decade, allowing some high-level trends to be discerned. The first trend is that the more China uses such techniques, the more others become involved in one way or another. China prefers to have bi-lateral relationships with other countries rather than work through multi-lateral channels, but gray zone activities tend to work against this. Others notice China’s assertiveness, worry about being picked off individually, and if not join in, at least passively support the country being targeted by China.

The South China Sea dispute has been running the longest and is now noticeably dragging in more countries. Originally, China sought to negotiate bi-laterally and then only grudgingly agreed to accept multilateral discussions under the ASEAN institutional framework. This has further evolved with many countries now issuing diplomatic Notes Verbales so as to involve the United Nations. Moreover, the dispute has been part of the rationale for the formation of the Quad, comprising the United States, India, Japan, and Australia. The Quad is steadily becoming a more cohesive, pseudo-alliance grouping, as India’s border troubles with China worsen, and China steps up pressure on Japan in the East China Sea. More third parties are piling in with the European Union’s (EU) views of China as a “systemic rival.” The United Kingdom, France, and Germany are now sending naval patrols to the South China Sea.

A second trend is that China is making increasing use of non-military means of coercion, particularly coercive diplomacy and cyber. A recent study found that over the past 10 years, there were 152 cases of such coercion affecting 27 countries and the EU, with a very sharp exponential increase in such tactics since 2018. In terms of cyber, China has long been noted for its cyber intrusions to steal intellectual property and industrial secrets. A recent shift though is towards using cyber means to inflict damage on others as part of a gray zone operation. In a notable recent example, China mounted a broad cyber-campaign against India’s electrical power grid that coincided with the 2020 military border clash. Both coercive diplomacy and cyber have major advantages in terms of giving a global reach. China’s gray zone activities can now impact very distant nations, not just those on its borders.

A third trend is a perceptible movement towards more violent actions, even if these do not involve armed attacks. In June 2020, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers killed twenty Indian soldiers in a border clash. Previously, China’s gray zone actions did not intentionally aim to kill others. The year also saw a PLA Navy warship aim its gun control director at the Philippine Navy’s anti-submarine corvette BRP Conrado Yap in the Spratly Islands. In the naval domain, this can be considered as a hostile act and seems the first time that a Chinese warship has directly threatened a Philippine government vessel in the South China Sea. A second incident involving a PLA Navy warship pointing a laser at a US Navy P-8 maritime patrol aircraft drew criticism from the U.S. Navy as being “unsafe and unprofessional.” This was a new step as such actions, while increasing in the last couple of years, have previously emanated from Chinese fishing vessels, not PLA Navy warships.

Wild Cards

Trends can only tell us so much. There is always a chance of a sharp deviation in the future onto a very different path. Four wild card possibilities are worth discussing.

Embracing Hybrid War. While China is destabilizing the existing international order through its gray zone activities, so also is Russia through hybrid warfare. China may be tempted at some stage to shift up the conflict continuum a notch, move beyond gray zone activities, and embrace Russia’s hybrid model.

Chinese gray zone activities aim to gain lasting strategic advantage over another (Chapter One, pp. 11-25). In contrast, the Russian armed forces define hybrid war as a war in which the means used, including military operations, support an information campaign. The aim of this campaign is to gain “control over the fundamental worldview and orientation of a state,” shift its geostrategic alignment, and shape its governance. China’s gray zone activities may irritate another, but the Russian hybrid warfare model tries for regime change.

Proxy Wars. China might not move as far as hybrid wars; however, its gray zone activities could be extended to include supporting proxy wars. In the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States fought each other vicariously through their various client states. Wars in countries as varied as Ethiopia, Angola, Nicaragua, and Afghanistan all engaged the superpowers of the day in providing overt and covert support for their chosen sides. If the U.S.-China relationship deteriorates into approximating a new Cold War, proxy wars may make a comeback.

Playing the Russia Card. There is a possibility that Russia and China may choose to actively work together. In this, there are uncertainties over the synergies their combined actions might generate, in particular how Russia might amplify Chinese gray zone efforts. Today, China is mainly leveraging its Russian relationship to fill gaps in its military capabilities and to accelerate its technological innovation.

In terms of gray zone activities, a new development has been the undertaking of joint China-Russian air patrols in the East China Sea. The first in July 2019 was heralded as taking the two nation’s military-to-military cooperation to a new level appropriate to ‘the new era,’ but finished with South Korean fighters firing warning shots when one of the Russian aircraft intruded into Korean territorial airspace.

Given this fiasco, a second try was not attempted until late December 2020. On the Russian side at least, this was somewhat larger in involving four PLA Air Force (PLAAF) H-6 bomber and 15 Russian aircraft, including two Tu-95 bombers, an A-50U airborne early warning and control aircraft, and 12 Su-35S fighters, presumably to warn off any pesky South Korean fighters. Communist Party media outlet, Global Times, optimistically forecast that “China-Russia joint aerial strategic patrol will become routine in the future,” while avoiding dwelling on the first patrol’s problems.

Nevertheless, such patrols hint at the possibilities of Russia and China at least coordinating actions in their border zones. For example, Russia might conduct hybrid warfare operations in Europe while China ramps up concurrent gray zone activities in the South and East China Seas. Such an approach of working together but separately could tax any Western responses.

Mirror Image. If China is pleased with its gray zone activities, there is a possibility that others might not just take up the technique but use them against China. China has more borders than any other country, leaving considerable space for nefarious actions. Moreover, the Party faces many domestic problems and continually worries about internal stability. A gray zone activity over an extended period, using diverse means, that was ambiguous, stayed within red lines, and exploited the Party weaknesses could be a definite annoyance, shifting the strategic advantage away from China to others. China’s gray zone sword might become two-edged, able to inflict damage on its originator.

The Shape of China’s Future Gray Zone Activities

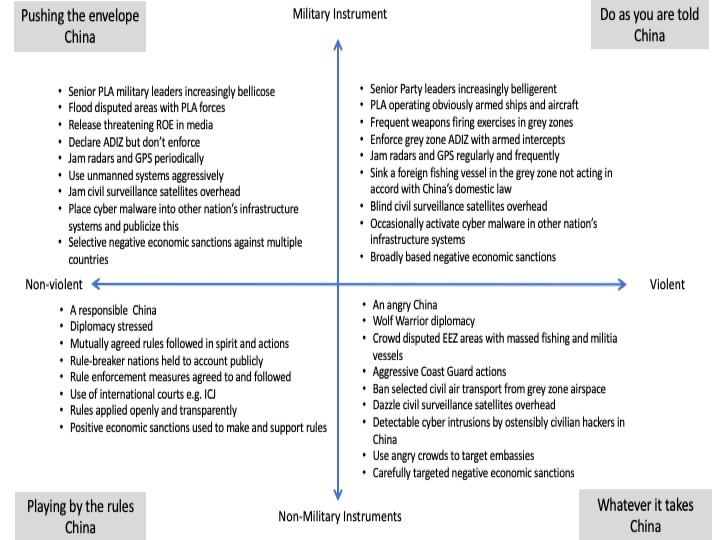

In general, gray zone activities involve purposefully pursuing political objectives through carefully designed operations; moving cautiously towards goals rather than seeking decisive results quickly; remaining below key escalatory thresholds so as to avoid war; and using all instruments of national power including non-military and non-kinetic tools. These characteristics suggest that in terms of its application in a specific circumstance, gray zone activities have two important variables. These are whether violent or non-violent actions are undertaken and whether non-military or military instruments are used.

The drivers created by these variables implies four possible alternatives as illustrated in the Figure below. These are the manner in which future Chinese gray zone activities might be undertaken. None of these four alternatives are considered more probable than the others, but that which actually occurs is hopefully captured within the wide span of possibilities encompassed.

The ‘playing by the rules China’ is an optimistic future where a responsible stakeholder China abides by the rules to which it has agreed with others. The ‘whatever it takes China’ is a minor deterioration from now and is perhaps a near-term prospect. The ‘pushing the envelope China’ is an evolved future where much greater use is made of the PLA but in a non-violent way. The ‘do as you are told China’ is a near worse-case possibility that is arguably on the limits of gray zone activities; there would be a high risk of peace breaking down and serious armed conflict starting. An indicator and warning of this might be the shoot down of an uncrewed air vehicle, such as a Triton maritime surveillance drone.

Long-term trends, wild cards, and the shape of China’s future actions combine to give an overview of the strategic- and tactical-level gray zone possibilities, but the future should not necessarily be thought of as simply getting worse. As gray zone activities are undertaken at the direction of the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership, they could just as easily be wound back towards something approximating the positive ‘playing by the rules China’ future. However, the killing of the twenty Indian soldiers on the border with China is a most worrying development. Prudence would suggest paying close attention to China’s near-to-medium term gray zone activities. This appears a “Danger, Will Robinson” moment where the omens look distinctly gloomy.

Dr. Peter Layton is a Visiting Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University and an Associate Fellow, Royal United Service Institute (London). A retired RAAF Group Captain, Peter has a doctorate in grand strategy and taught national security strategy at the U.S. National Defense University. He is the author of the book Grand Strategy. His papers, articles, and posts may be accessed here.

Featured Image: A Google Maps Street view of the Chinese embassy in Washington, D.C.