Guest Post by Matt Puterio

At Naval Undersea Warfare Center (NUWC) Newport we recently began an internal investment project—the Seamless and Intuitive Warfare Workforce Development Project—to develop the next generation of “system of systems” engineers. These engineers will ideally be trained to view problems and develop solutions in a holistic manner, breaking from the stove-piped designs of legacy systems. As an underlying theme for the effort, NUWC Newport focused on the “One System” vision for submarine tactical systems. This idea was originally conceptualized at the Tactical Advancements for Next Generation (TANG) forum and further advocated by the submarine fleet. In pursuit of this vision, the team explored potential improvements for submarine combat system interfaces and for the control room as a way to improve the information flow and the effectiveness of the control room’s contact management team.

Our Approach:

- Team formation: We recruited and selected a cross-departmental team of 10 young engineers, typically with 3-7 years experience, from the Sensors and Sonar Systems, Combat Systems and Electromagnetic Systems Departments at NUWC Division Newport.

- Baselining on current combat systems: We cross-trained the team using military personnel in the Combat Systems Collaboration And Fleet Experimentation (CAFÉ) laboratory on an end-to-end layout of a Virginia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) control room, driven by a Submarine Multi Mission Team Trainer (SMMTT) system with sonar and combat control watch teams. An imaging simulator was even used to populate the periscope view with surface contacts when operating at periscope depth.

- Innovation process: The team brainstormed initial concepts for next-gen integrated tactical systems, generating around 40-50 ideas, from which about 8 concepts were selected by the team for early prototyping with mock-ups. These mock-ups were cut-out model representations using basic materials such as foam-core, cardboard and coloring sheets; and served to focus the team’s attention on details of scale and placement that would not have otherwise occurred.

Today’s Sailors are accustomed to immersive video games, advanced smart phones and tablets, intuitive multi-touch applications and can easily navigate the highly networked and always-connected world in which we now live in (so-called ‘digital natives’). Our project aims to leverage this natural affinity coupled with advanced technologies such as high resolution multi-touch displays, and mobile computing devices, and new software concepts such as cloud computing and virtualization and apply them to the demanding needs of the tactical warfighter. Sailors should be able to seamlessly adapt their high-tech civilian skills to the world of Undersea Warfare with minimal re-training and Seamless and Intuitive USW is focused on making this goal a reality.

The innovation process we followed was modeled after one developed by design and innovation consulting firm IDEO; the same process used by the TANG workshop. Generating a series of “How might we…” questions (called HMWs), the group brainstormed ideas for what improvements could be created. The members of the brainstorming group then came up with ideas to answer the questions (e.g. “redesign the layout of the control center!”) and wrote their ideas along with descriptive pictures to better explain the idea on sticky notes; one idea per sticky. Emphasis was on rapid and not necessarily well thought-out ideation along with quick sketches for each idea. The fast-paced nature of this exercise kept team members excited and stimulated creativity.

After investigating each idea, the group voted on the ideas they found most interesting, most powerful, or most disruptive. Sub-groups of 2-5 team members were formed, and each sub-group picked a high scoring response to a HMW question that they would like to prototype. This stage of prototyping was very basic; 4-K displays, iPads, iPhones, Android tablets, cloud computing, and multi-touch monitors took a back seat to foamcore, construction paper, hot glue, whiteboards, Sharpies, and dry erase markers. The immediate goal wasn’t to get an actual product out to the fleet—rather to build a better mental model of the top ideas before laying the groundwork for an actual system. Some of our prototypes at this stage included an operator workstation stack built out of foamcore, models of how we envisioned the layout of futuristic control rooms built from construction paper and foamcore (complete with popsicle stick sailors), and a 3D-display made from transparency sheets and foamcore.

Building rough prototypes literally turns words on paper into tangible objects. Tangible objects are easier to work with since they do not require the imagination of onlookers and fellow team members. A 3D-display may seem unnecessary until a fellow team member shows a physical model with a clay “ownship” submarine at the center and contacts of interest at various ranges and bearings on the display, directly modeling the actual tactical picture in the current environment.

From here our Seamless & Intuitive USW group branched out in two directions; software application development and virtual worlds (VW) modeling. The “App Team” focused on taking the most promising and realistic rough prototypes (in terms of team skills and project timeframe) and prototyped them in an actual software environment. This year we had access to a Perceptive Pixel multi-touch workstation with the Qt development environment that enabled us to quickly put together a few simple applications to interactively demonstrate the same concepts we prototyped using the arts & crafts materials. One example was a “Multi-touch App Manager” which allowed a user to pull open a menu of “available apps” similar to the app icons on Android or iOS, and resize and drag individual “apps”—simply static tactical screenshots in our prototype—around the workspace. Other examples included a demo of three different ways to select a trace on a display and a “Five Finger” multi-touch menu that enables users to pull open an intuitive menu simply by placing their right or left hand on the display surface.

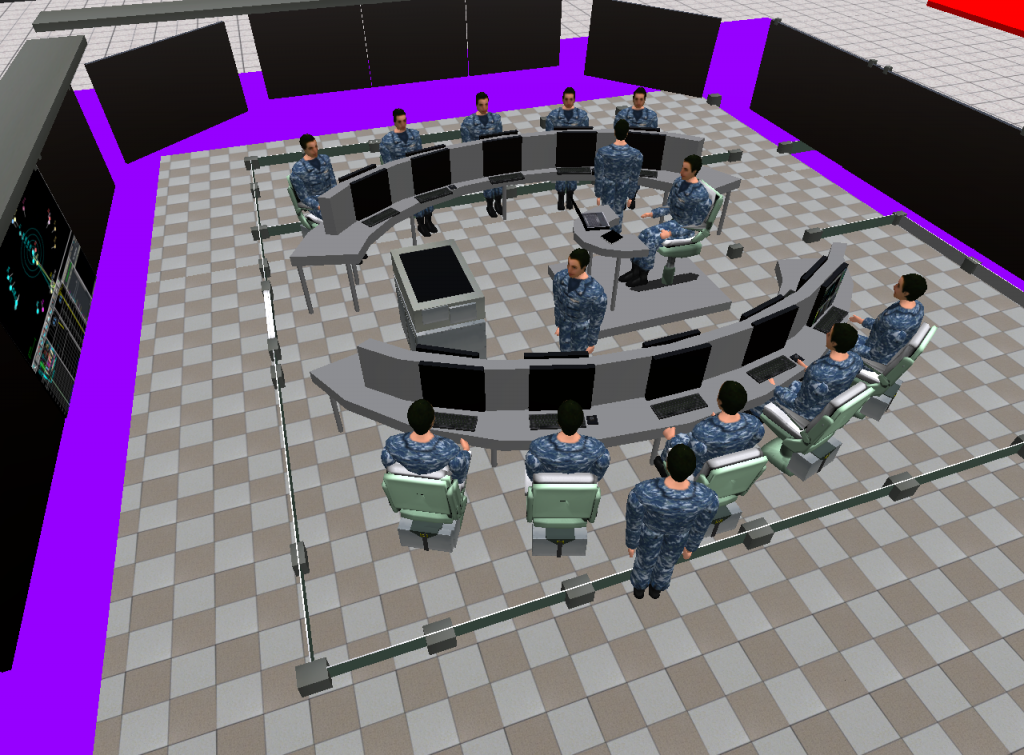

Some of the ideas we brainstormed couldn’t adequately be represented in software. Rather than build a full-sized model submarine control room, the other branch of our group, the “Tiger Team,” employed their modeling skills with Second Life, a virtual world simulator. The Tiger Team worked with the “Virtual Worlds” group at NUWC, a team with expertise in creating realistic virtual models of Navy ships, submarines, and facilities in Second Life. The Virtual Worlds group assisted the Tiger Team in building realistic models of concepts such as new control room layouts, next-generation displays (such as the previously mentioned 3D-display), and even interactive displays by utilizing Second Life’s VNC capability (see below for an inward-facing command center configuration).

The next step from here is implementing these prototypes on live data-streams, and integrating them as advanced engineering modules into a tactical system. So far we have given various demonstrations of our concepts, and have received overwhelmingly positive feedback from our colleagues, internal NUWC management, and fleet representatives from Submarine Development Squadron TWELVE at the annual DEVRON12-NUWC Tech Exchange. The simplicity of the design-thinking process allowed our small team of engineers to go from ideas on sticky notes to working software prototypes and virtual models in several weeks.

We are eager to continue our work on Seamless and Intuitive USW. In addition to being an excellent platform for idea formation, this project was fun, exciting, and served as a vehicle to achieve our objective of developing the next generation of “system of systems” engineers. Working with next-generation technology is always a pleasure, and the expectation that our ideas will make it onto a shipboard system and help sailors perform their functions better makes our work even more worthwhile.

Contact Information:

Project Lead: [email protected] 401-832-3887

Co-Lead: [email protected] 401-832-8207

Matt Puterio is an engineer in the Sensors & Sonar Department and has been with NUWC Newport since June 2012 after graduating with a degree in Computer Engineering from the University of Delaware. His work includes test and analysis on the SQQ-89/ACB-13 surface ship sonar program and also works with Ray Rowland on the Seamless & Intuitive USW program.

At the operational level, planners can expect warfare to range from the multiple-battalion level assault on

At the operational level, planners can expect warfare to range from the multiple-battalion level assault on