By Mie Augier, Major Sean F. X. Barrett, and Major Kevin Druffel-Rodriguez

Major General William F. Mullen III, USMC, retired as Commanding General (CG), Training and Education Command (TECOM) on October 1, 2020, completing a career that featured an unusually vast amount of experience across Marine Corps training and education commands. Major General Mullen commanded Marine Corps Tactics and Operations Group at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center (MCAGCC) Twentynine Palms, CA, and he also served as President, Marine Corps University (MCU), concurrently serving as CG, Education Command, as well as CG, MCAGCC.

While CG, TECOM, Major General Mullen spearheaded the effort to publish Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 7 Learning, the Marine Corps’ first new doctrinal publication issued since 2001, to explain why learning is critically important to the profession of arms. In the conversation that follows, we discussed some of the themes in MCDP 7, learning to become learners, and the importance of building learning cultures in warfighting organizations.

What inspired your own interest and curiosity in learning, and how did you first experience the benefits of being a lifelong learner?

I have always been interested in learning and reading and what it can do for you. But I had never heard it articulated how much it can actually do for you until I was a company commander at 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines. The battalion commander was LtCol John R. Allen (later General Allen), and he exemplified everything that was possible with reading, the 5,000-year-old mind, for example, and using that for knowledge and experience.

As an example, we had a short notice deployment to deal with Haitian and Cuban migrants. Before we deployed, he gave us a couple chapters of problems the U.S. Army had had with POWs (prisoners of war) in Korea as a read-ahead for the things we would likely face (e.g., dealing with large, angry crowds). Reinforcing this, LtCol Joseph F. Dunford (later Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Dunford) took over as battalion commander after Allen, and he also exemplified this ideal of being a lifelong learner. They showed us what was possible from learning. They were so far past their peers in their ability to think and execute, and it kept getting better as they became more senior.

You argue the mind is a muscle and therefore atrophies when not exercised. This metaphor conveys not only the importance of learning, but also introduces an element of “pain.”1 What is the origin of your understanding of this metaphor?

We all know that Marines like to exercise, so when I was talking to them for my “PME on PME” lecture,2 one of the things I was trying to get across is that your brain needs to be exercised as well. I would ask them what happens if you don’t PT, you don’t exercise. Your muscles atrophy. Your physical abilities atrophy. The brain is the same way.3

In the past, I have read studies about Alzheimer’s patients and how to stave off the effects of memory loss. I noticed that people who stayed more mentally engaged, learned new languages, read a lot, and played challenging games were able to exercise their mental synapses, which allowed them to continue to think and be engaged instead of atrophying. Regarding the whole pain aspect, I would ask them, “How many times have you read a really hard book, and you are trying to work your way through it, and your brain is just tired?” This is just like a strenuous exercise, but for the mind. For me, philosophy is that way. I try and read it and work through it, but I have to take it in small doses because it is tough.

One way to train the mind-muscle is by reading. How did you become someone who reads broadly?4

Part of it is that I read fairly quickly, and that was developed when I finished being a company commander. I went to Inspector-Instructor (I&I) duty in Milwaukee and got back into my alma mater to get a Master’s in Political Science. So, I was working on my Master’s, working I&I duty, which if you do it right is more than a full-time job, and I was also doing my Command and Staff (non-resident course) box of books all at the same time. I had to figure out ways to read quickly. I wrote an article called “Advanced Reading Skills” that came out in the Gazette that talks about the process and how I did all that.5

I always knew I wanted to cast my net widely, but I couldn’t really articulate it until I saw LtGen Paul K. Van Riper articulate it. He said we are trying to understand human beings because we lead human beings. We try to get them to do things that they naturally would not do. How do you understand human beings? How do you understand all the things that impact our ability to get our job done if you aren’t reading widely? Some people say, “I never read fiction,” but some of the most creative things I have ever come across, with regards to ideas, are in fiction. Some of the things you read about, you ask, “Why can’t we do that?” It gives you ideas. When it comes to understanding the human condition and what makes people tick, human beings really haven’t changed that much. The character of war has changed, but the nature of war hasn’t. It is still human beings going against each other—opposing wills. So how do you understand people and what makes them tick?

What books have you found useful for inspiring others to pursue a lifetime of learning?

I wrote an article, “A Warriors Mind,”5 in which I talk about the different categories if you want to know more about this and all the books I listed. There are only five in each category. One of those categories is, “How do you hook their interest?” How do you get them reading more? That came from watching the phenomenon of the Harry Potter books. Kids who really wouldn’t read anything were reading books that are 700-800 pages long and just eating it up. That hooked their interest, and then they expanded onto other things because they realized that reading is not a chore. It is actually enjoyable.

So how do you get them interested? Where are they at intellectually? Where is their vocabulary? What is their comprehension level? Those are the important things because if you hand someone a dense book, and they haven’t been reading much, that’s a dead end. But if you hand them some other things that you can use to build up to something high-end, that’s a better approach. So, I would ask them, “Where are they at now, what have they read?” The biggest thing that has hooked people’s interest is historical fiction, especially well-written historical fiction. That really gets them enthusiastic and wanting to learn more, and they start expanding their interests from there.

MCDP 7 Learning has been out for a year now. How did it come together? And with the benefit of hindsight, is there anything you would have done differently? For example, are there any additional topics you would have included or ideas you would have framed differently?

To clarify, I didn’t write it. I had a writing team who did the writing, but it was my idea to initiate the writing of it, and I was heavily involved in the editorial process and reviewing it. I would go back to them and ask questions, ask them to factor in things, and try to get it “MCDP 1-like.”

The inspiration for doing it was frustration. MCDP 1 is our foundational document. It is our maneuver warfare philosophy. It is supposed to be the basis for everything we do, but a majority of the folks in the Marine Corps don’t understand it, mainly because they have not read it. For those who have read it, they have not read enough around it to understand what it means, how you operationalize it, because we aren’t studying our profession.

There are a lot of folks who just can’t be bothered. “Reading is a chore,” or “I joined the Marine Corps so I didn’t have to go to school anymore.” Officer, SNCO, enlisted, it doesn’t matter—everybody needs to understand it. So learning is about how you go about learning your profession. Continuous learning is a lifelong pursuit, and it is the only thing that enables you to understand what MCDP 1 says and how you then operationalize it and live by it in your units. Education prepares you for the unknown. What happens when plans have to change? And that always happens. Education is far more important than training.

What would I do differently? Right now, I can’t say that I would do anything that much differently because the main emphasis was to get it out in recognizable form. I sent it out to a couple of people, a number of people who I highly respect. Some of them came back and said, “We don’t need it,” and I was a little frustrated by that response, until I realized: Well, they lived it. Of course, they understand it, it is intuitive to them.

No, they didn’t need it, but it is not for them. It is for all of those folks who do not understand and don’t understand the why—why learning is so important. So I can’t say that I’d do it any differently. But I can say that it does need to be reviewed in about five or ten years or so. Take a look at it and see what needs to change to keep it current with education technology and the theories going on. But it was also to prod, to help change the Marine Corps from industrial age learning to information age learning, which is a very different approach, and we are not built that way. And we needed some serious dynamite under our foundation to break out of our bureaucratic processes.

You wrote the TECOM guidance that led to MCDP 7 and also had some interesting thoughts about how to take PME beyond the industrial age. What motivated you to issue that guidance?

The big piece was the why—why learning was so important. I have been talking about it for years, doing the “PME on PME” lecture as well, and advocating for it well before that—because of what I was seeing: the lack of people studying their profession and understanding the requirement to learn.

And then, thinking about what it would take to start to try and change the culture of the Marine Corps to become more of a learning culture. We were explaining the why and trying to get the culture to change through a doctrinal publication. I didn’t expect it to have the importance of MCDP 1, but I remember the Commandant, General Robert B. Neller, asking the question, “How do we re-invigorate maneuver warfare?” The reason he asked that question was that most people have not read it, they have not studied it, they haven’t studied the requirements.7 And all of this came together, and I talked with General David H. Berger when he was in his Deputy Commandant, Combat Development and Integration (DC CD&I) job, my immediate boss my first year at TECOM, and he thought the idea had merit. And then when he became Commandant, we sent it up to him after a brief review process, and he signed it.

So you had a little bit of inspiration from FMFM 1?

Yes, absolutely, because you have to understand how to take intelligent initiative. You have to understand what intent is and then be able to have the mental agility to adjust as things change around you. All of that requires continuous learning. If you decide that you don’t need to learn anymore and that you left all of that behind when you left school, you end up with people who might take the initiative—but there’s a good chance it is the wrong initiative.

MCDP 7 refers to learning organizations and learning cultures. How do these organizational elements interact with individual-level learning, and how can we cultivate them more effectively?

We have to set the foundation for the expectation that when you join the profession, continuous learning and continuing professional development during the career—ideally, through life—is absolutely required. And if that is too much work for you, then you need to find employment elsewhere. Because the way I look at it is, if we are not studying our profession, if we don’t keep up with it, it is like a doctor or a lawyer who stops studying. Who wants to go to them?

We are in the most intellectually and physically demanding profession on the face of the earth, and the price of getting it wrong is that the people we are in command of end up dying.

We shouldn’t have to figure it out by filling body bags. But we do, too often. I saw it in Iraq, I saw it in Afghanistan. And that is not right.

There should be the understanding that learning is something you need to get after as a professional. But if you don’t because you are young, and you just haven’t figured that part out yet—whoever is in charge of you should tell you, “You better get after it! Here are some ways to do it, and let me help you with it. Here are some things to read, we are going to talk about them. I will help coach you and move you along.” That is the kind of thing that has to happen in a good profession and in a good unit.

How do active learning approaches benefit leadership development?

Part of it is taking responsibility instead of needing others to push you through things. One of the active learning experiments we did was out at the Marine Corps Communications-Electronics School (MCCES) out at Twentynine Palms. One of the questions I asked when I first took over was, instead of Marines having to wait around to join a course, can’t we hand them a syllabus as soon as they show up, preferably on some electronic device? They start to read through the syllabus at their own pace. If there is a lab requirement, it is hands on, it is available to them 24/7. The instructors are there to coach, teach, mentor, and help them through the process, and they work through it with their peers—but they work at their own pace. And when they have demonstrated the necessary level of competence, they move on, cutting down on time waiting around.

In the experiments we did, the Marines loved it. We experimented at Marine Corps Intelligence Schools, and the Marines loved it. There were a couple of other places where we experimented. We need to be able to take advantage of the fact that the young Marines are smart, great with technology, and can learn at their own pace. It also is then about building trust by giving Marines control over their learning. Let them show initiative as well.

In both MCDP 7 and your “PME on PME” lecture, you talk about the importance of critical thinking, judgment, and decision-making. What other important post-industrial age skills and attitudes do you find important, and how can we improve at cultivating them in our PME institutions?

The understanding that comes from continuous learning—being better educated, being more openminded, being more mentally agile—makes Marines more capable. Some people have advocated that the kinds of skills that special operations forces (SOF) have are needed—the maturity, the knowledge, the skills. I’m not advocating that we need to be SOF, but we certainly need to be more SOF-like. We have to get our Marines more mature, better focused. In today’s operating environment, people have to be able to think, take the initiative, have good judgment, and understand what is going on around them.

Thinking about the differences between rote memorization and critical thinking, what shifts have to occur to transition from teaching warfighters what to do and what to think to how to think critically and independently?8

Part of it is getting out of the bureaucratic process we have established and that has been ground into everybody, probably since the mid-1960s. TECOM is part of the problem because we inspect that process, the industrial age process, which tells people what to think, which encourages them to sit down and wait to be told what to do.

So, shifting out of that—one part of that was sending a letter to the commanders of all the schools in TECOM saying, “Now you have the authority to experiment. Tell me what you want to do. And that is what we will hold you to, and no longer the part of the inspection process that does not apply.” But we need to figure out how to do that in the most effective manner—not necessarily in the most efficient manner. Efficiency is good, but it is less important than effectiveness in my mind.

How do you shift, and how will it look after? I don’t have the answer right now, but we need to at least start moving, and that is what we are doing. We have started, but we need to expand. Every Marine knows he or she may get called to go into combat or to support it. They need to be able to show initiative and figure out what to do, not wait around to be told.

You mention the importance of experimentation, active learning, and critical thinking. What are some of the critical barriers to cultivating and implementing them in our organizations?

For sure, bureaucracy and the inspection process—the formal school’s inspection process, which holds people in a straitjacket. And what I experienced was, some colonels, as soon as you gave them an inch, and the ability to experiment, they took it and ran like you would expect a good colonel to do. Others were very hesitant, didn’t know what to do, and said, “No, we are just going to continue doing what we are doing.” And that was tremendously frustrating. You have been given guidance. Here is the intent. You have top cover—get after it. You have the ability to take some risk, especially in a training environment where the risk you are taking is being more effective and making sure Marines understand.

One of the buzzwords I had was we have to get away from focusing on process, and we have to focus on product. What do the Marines understand and retain once they move out to the operating forces? That is what is most important. Everything we do should focus more on that: helping them understand more, retain better, think better—not the process of just moving things through and making sure you have all the “i’s” dotted and all the “t’s” crossed. That, to me, is our biggest obstacle: our own processes and bureaucracies and being so focused on process.

Major General Mullen was commissioned in 1986 and served 34 years as an infantry officer, serving in the operating forces with 1/3, 2/6, and RCT 8. He participated in Operation SEA SIGNAL dealing with Haitian and Cuban migrants, Contingency Operations in the former Yugoslavia, several counter-narcotics operations, as well as three combat tours in Iraq. Supporting establishment tours included the FAST Company, Pacific; Inspector-Instructor, F Company 2/24; Marine Aide to the President; the Joint Staff; and, CO, MCTOG. As a general officer he served as President, Marine Corps University; Director, Capability Development Directorate; Target Engagement Authority for Operation INHERENT RESOLVE; CG, MCAGCC; and ended his service as CG, Marine Corps Training and Education Command (TECOM). Major General Mullen retired on Oct 1, 2020 and is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Colorado. He also recently started as Professor of Practice at the Naval Postgraduate School (Graduate School of Defense Management). He co-authored the book Fallujah Redux which was published in 2014.

Dr. Mie Augier is Professor in the Graduate School of Defense Management, and Defense Analysis Department, at NPS. She is a founding member of NWSI and is interested in strategy, organizations, leadership, innovation, and how to educate strategic thinkers and learning leaders.

Major Sean F. X. Barrett, PhD is an intelligence officer currently serving at Headquarters Marine Corps Intelligence Division. He has previously deployed in support of Operations IRAQI FREEDOM, ENDURING FREEDOM, ENDURING FREEDOM-PHILIPPINES, and INHERENT RESOLVE.

Major Kevin C. Druffel-Rodriguez is an active duty Marine Corps combat engineer officer. He is currently the operations officer for the Headquarters Marine Corps Directorate of Analytics & Performance Optimization.

References

[1] Mortimer J. Adler, “Invitation to the Pain of Learning,” Journal of Educational Sociology 14, no. 6 (Feb. 1941): 358-363.

[2] “MajGen Mullen’s PME on PME,” October 17, 2019, Marine Corps Association, video, 1:41:49, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcPSB5Edbx4.

[3] One of the more interesting receptions of MCDP 7 is Jocko Willink, Echo Charles, and Dave Berke’s detailed reading of it on Jocko Podcast. They discuss important themes in MCDP 7, such as continuous learning and needing to exercise your mind. Jocko Willink, Echo Charles, and Dave Berke, “227: Learning for Ultimate Winning. With Dave Berke. New Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication. MCDP 7 Learning,” April 29, 2020, Jocko Podcast, podcast, 2:21:27, https://jockopodcast.

[4] Epstein notes the importance of intellectual range and agility in David Epstein, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World (New York: Riverhead Books, 2019).

[5] William F. Mullen, III, “Advanced Reading Skills: Techniques to Getting Started,” Marine Corps Gazette Blog (Apr. 2019): B1-B5.

[6] William F. Mullen III, “A Warrior’s Mind: How to Better Understand the ‘Art’ of War,” Marine Corps Gazette 103, no. 6 (June 2019): 6-7.

[7] For a more detailed discussion, see William F. Mullen, III, “Reinvigorating Maneuver Warfare: Our Priorities for Manning, Training, Equipping, and Educating Should Be on Our Close Combat Units,” Marine Corps Gazette 104, no. 7 (July 2020): 62-66.

[8] For an overview of some changes already underway in the Marine Corps, see Gidget Fuentes, “Marine Infantry Training Shifts From ‘Automaton’ to Thinkers, As School Adds Chess to the Curriculum,” USNI News, December 15, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/12/15/marine-infantry-training-shifts-from-automaton-to-thinkers-as-school-adds-chess-to-the-curriculum.

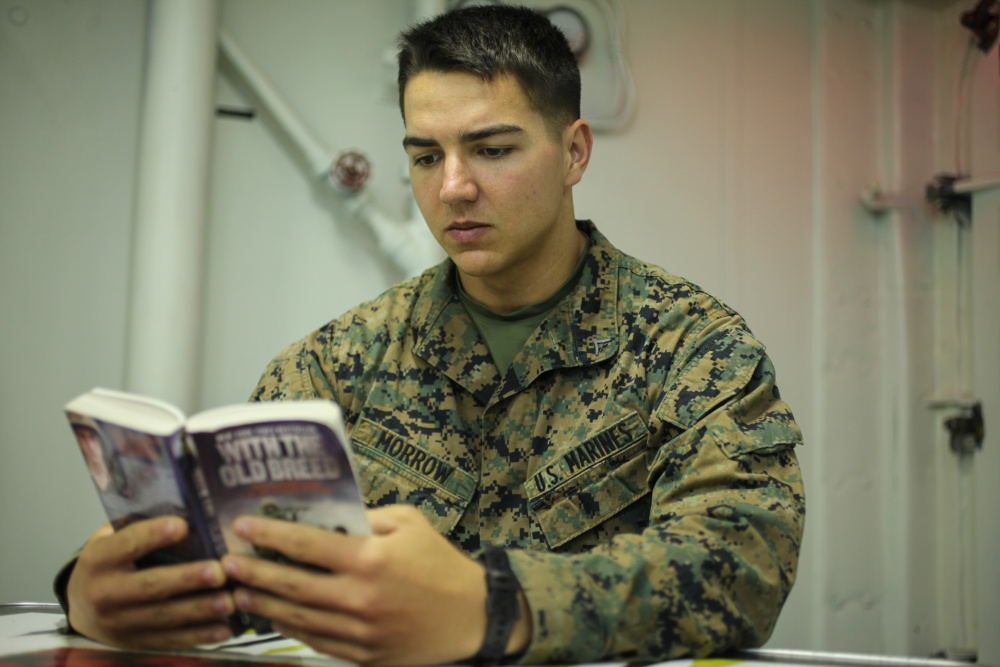

Featured Image: PEARL HARBOR, Hawaii (Jan. 10, 2020) – Marines and Sailors with the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit’s Maritime Raid Force secure a simulated casualty during Visit, Board, Search and Seizure training. (Official U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Isaac Cantrell)