Fiction Topic Week

By David Poyer

What would happen if “Thou Shalt Not Kill”….became one of the Laws of War?

“Drop!” screamed Loftis, his body thumping grass and dead leaves. He slapped his mask down and offed his safety at the same instant.

“Right clear.”

“Left flank clear.”

“Rear clear, Sergeant.”

When the squad moved warily out onto the crest, breathing hard from the climb, the patch of black Loftis had seen from two hundred yards away was still there. He waved the squad back and moved forward alone. Low and slow.

This had been a pasture once, this bald patch atop a hill. The russet remains of haystalks hissed against his boots. The bush was ninety meters away, a band of green hazed by the mist of early dawn and the double glaze of mask and his BattleGlasses.

When he reached the Russian he paused, searching the tree line, then dropped to a knee. He saw the rise of shoulderblades in breath. Quickly, moving clear as he did so, he rolled the man over.

Fear took his bowels. In six months of war he’d fought across half of Ukraine, first going one way, then the other. Battlefield promotion from lance corporal to sergeant. But he’d never seen this.

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

“Holy Jesus,” said a muffled voice behind him. He turned his head. It was Branch, the replacement, standing tall and thin as a goal post. Her weapon dangled in her gloves, and under her shoved-back hood freckles had bleached pale. “What’s the matter with him?”

For answer Loftis kicked out. The private thudded to the ground, but she rolled, protecting her rifle instead of herself. Good, he thought. Maybe she’s trainable. But aloud he hissed, “Stay down, shithead! You make a target like a popup at SOI!”

“Sorry, Sergeant. But…what’s wrong with him?”

Loftis stared at the body, unsure what to do. He peeled the black uniform cloth away. It was stiff. Gas-impregnated, like the Marines’ colorchanging Cameleons, but cotton rather than synthetic. His hand came away wet, and he lifted it to the waxing light. It glistened.

“He’s wounded,” he said. Branch’s eyes grew huge.

Loftis rolled over and examined the sky closely. It was blue, cloudless, and open as a mouth ready to bite. He did not like it at all. He pulled a grenade from his pack and threw it as far as he could upwind. It popped and dark green smoke rolled across the pasture. “Send Joynes and Oleksa up here. We got some crawling to do.”

This time he didn’t have to repeat the order.

Sergeant Olin Loftis’s arms bulged under his Cameleons and his boots gripped dirt like the piles of a bridge. Another boot had broken his nose with a pugil at Camp LeJeune and it was humped and spread even more than it had when he was born, two and a half decades before, in Northeast DC. His chin was rough with ingrown beard, and he rubbed it now as he considered the man who sat, waxen-pale, slack-headed, against the bole of an oak on the shaded side of Hill 1132, twenty kilometers behind enemy lines in War Zone J.

“He gonna make it, Doc?” he asked Joynes.

The dark-haired corpsman was squatting on his heels, stuffing gear back in his kit. He was Navy, not Marine. He wore the red cross on his shoulder. He didn’t carry a weapon and wasn’t gung ho. Before the war he’d been a teacher, and still liked to quote men no one else in the platoon, including the officers, had ever heard of. Usually his expression was skeptical; now he looked grim. He glanced at the wounded man. “He lost a lot of blood. But he’ll make it.”

“Is he mobile?”

Joynes considered. “When he comes around he ought to be able to stagger. Wound’s in the meaty part of the thigh, but it missed bone. I gave him glucose and benzedrine and a combat ‘dorph. But he’ll be hurting, and he’ll be slow.”

“How’d he get it?”

“Bullet wound.”

“Whose?”

“Oh, come on, Sergeant. How can I tell that? Another stupidity of a stupid war by a stupid species.”

“Fuck me,” Loftis muttered. He looked up at the foliage, which swayed in a gusty wind. The leaves were turning and the wind had an edge, not cold yet, but warning of winter. The men watched him. When he’d gone through his vocabulary he sat on his heels and stared at the Russian.

Blue eyes had opened during the tirade. They searched their faces wonderingly. His hair was the color of their cardboard ration containers. His lashes were long and his cheekbones heavy, his lips thick, smiling, just a trace, at the corners.

Their existence must have hit him then, penetrating endorphins and shock. His head and shoulders swiveled from the sergeant with the sudden movement of a reptile, and came face to muzzle with Stankey’s M22. He hesitated, then sank back against the bole.

“Speak English?” said Loftis hopefully.

Their enemy’s eyes narrowed. He looked, the sergeant thought suddenly, like the white man who owned the auto shop he’d worked in before the Corps.

“Shto’ vui skaz’ali?” he muttered.

Loftis sat back on his heels. “Jack, you talk some Slav, don’t you?”

“My grandma did, a long time ago.”

“Whatever, it’s more than me. Come up here and help me out.”

Jack Oleksa was a reservist, a corporal. He was old, over thirty. He was the smallest, too. He said very little. Before the war he’d worked in a post office, before they all closed. Oleksa settled down by the prisoner. He popped a ration vape and offered it to the Russian.

“What’s your name?” Loftis began.

The man stared up at them.

“Kak vas’ svatz?” Oleksa said, sounding unsure of himself. The Russian studied him, then held out the vape. Oleksa showed him how to turn it on. Both men shielded the smoke from the sky with their gloves.

“Why you want name?” he said, surprising them all. His accent was thick but they all understood.

“You figure it,” said Loftis. “We found you on the hill back there. You’re wounded. There’s no ump with us.”

“Family name Agayants,” the man said slowly. He looked at Loftis squarely. “Vladimir Agayants. Which of you shoot me?”

“None of us, goddamn it. Don’t you know who shot you?”

The prisoner shook his head silently. Again suspicion slid over his eyes, like the nictating membranes of an owl. He shifted his leg tentatively. His face went white, but not a muscle moved. He put the vape to his lips and sucked so hard his cheeks hollowed.

Says he doesn’t know who shot him, Loftis thought. True? False? The wound was bad but not fatal. Could he have done it himself? No weapon when they found him. But he could have done it in the woods, thrown the gun away before he passed out.

But why would he do that? Where had he gotten a conventional firearm? And why was he in the open? If I were wounded I wouldn’t go into the open, he thought. No, wait, I might if I was behind my own lines. That way the Eyes could see me. Maybe.

What if someone else had shot him? Say…his own side? There could be logic in it. Propaganda. But wouldn’t he remember?

He wanted to ask more questions. But the crickets were tapering off their morning song. He turned on his tablet and called up the map. As if that were a signal the squad moved closer. Even the Russian looked interested.

Things do not look good, Sergeant Loftis, he told himself. He studied the screen.

Two days before the line had crumpled under a sudden attack. The lieutenant, before they’d lost track of him, had said there were four Russian divisions opposite the sector fronted by the First Marine Brigade, supported by the 23rd Polish, on their left, and the U.S. First Army, on their right. A three to one force ratio, considering the lower tooth to tail of Allied versus Opposition light troops.

Loftis didn’t know how, whether it was misunderstanding, tactical foulup, or simply stronger enemy pressure, but the battalion’s right flank had been turned. The next morning brought an all-out attack. A heavy shockshell barrage hit as they sat around morning meal, followed by dozens of short-range drones spewing PK at bush level. Behind them came infantry. The sky was crossed with contrails as the air battle seesawed. The popcorn rattle of weaponry on the platoon’s flank built to a roar.

They held through the morning in savage short-range firefights before the tactical withdrawal began. It went on into the evening, with the platoon turning every hour to fight another delaying action. If a man fell he had to be left. By nightfall there were gaps in the retreating lines. When dark came, the blessed dark that all the Marines had cursed and prayed for through the day, the lieutenant came by to give him the order.

Rear guard. Loftis smiled bitterly. Take charge of a squad, hold till dawn, then rejoin. But when dawn came the battalion was gone, his squadtalk earset was full of the buzzsaw whine of jamming, and the hills were thick with black uniforms.

It was time to do some of that ridge-running.

He bent to the map. The first-stage stabilization line for the corps was Lubny-Kremenchuk, with the Dneipr on their right flank. He measured. Twenty-five klicks. Not too bad, though in rugged terrain like this bird kilometers turned into two or three on the ground. But they could do it in a day. We got to do it in a day, he thought, glancing at the sky through his leafy screen. If the Allies couldn’t hold there they’d fall back farther.

They had to rejoin fast, or they’d be trapped so deep in enemy territory they’d never get out.

Loftis looked at the Russian. He had tilted his head back against the tree. Resting. Most of the squad was looking at him. Only one Marine was watching Loftis. She’d set her rifle aside and was resting her hand on his utility knife. Her eyebrows rose slowly in a question.

Loftis stood. He flipped up his hood. The squad sighed. They knew the signal. As each Marine climbed to his feet he or she wedged the earset into the aural meatus, settled his BattleGlasses, tightened his hood, adjusted the bulky mask for instant donning, and checked her weapon. From a group of griping youths they became gargoyles, the deindividualized and faceless warriors of a new century.

Loftis studied the intent eyes, the hands nervously gripping weapons and packs. Oleksa. Joynes. Stankey. Branch. All who were left of the squad. They weren’t numbers to him. They were his people. The men and women he had to bring back.

And I will, he promised each of them silently.

“Les’ go,” he muttered. He extended a hand to the Russian, wiggling his fingers impatiently. “Means you too, Waldimeer. From now on, you’re tight on me.”

“What you doing, sarge? We can’t take him!”

Thin, wiry, street-smart, street-suspicious, his aggression and fear masked by sleepy eyes, Leopold Stankey could have been him six years before. He understood Stankey. He was hard to handle, but in battle he was one of the best. “Shut up, Private,” he muttered, holding the man’s eyes. “Do it.”

Branch’s knife slid back into its sheath. Loftis raised his arm, and tired legs swung into the first step.

Hours later, after a long downhill tramp, they reached the southern end of the ridge line. Loftis, filtering slowly down a wooded ravine, studied the trees, the ground, the ferns that nodded here and there among the fallen boles. Ukraine. In his mind it blended together, forest, rocky farms, the pitiful hamlets folded between hills like jelly in a doughnut.

In all this immense forest there were no civilians. Once there had, before the war. Sometimes the men would come upon vacant homes, farms, broken into by troops before them eager for food or a bed. But there were no people.

As they moved down the long slope, zigging from cover to cover, he wondered where they all were. Maybe they’d all evacuated. Maybe they were in camps training. He had no idea. It was another funny thing about a very funny war. So funny the enlisted had coined a funny-sounding name for it.

They called it the Sneekle War.

It had begun like all wars, with failed politics. The first failure was in the fragile coalition that was Europe. The Donbas Autonomous Republic had asked the Russian Federation for “fraternal assistance.” The Ukrainians, by now used to French wine, Greek music and American TV, called on NATO.

The Poles had responded, the Marines had landed at Odessa, and the Russians were rolling forward, when it happened. The General Assembly unanimously resolved that if the two blocs resorted to war – or violence in any form – they would be ejected from the world body, which would reconstitute in Beijing and isolate them both with the mother of all embargos. The president, after some initial waffling, agreed. Yet somehow, Ukraine had to be resolved; and the troops were already there.

The Secretary General had a suggestion.

One month later, SCLE(NL) began. Sub-Conventional Limited Engagement, Non-Lethal. For the first week nothing happened; nothing could. But quickly-modified weapons were airlifted from the States, and arms techs worked feverishly at Almaz-Antey and Uralvagonzavod. Those early battles were fought with makeshifts and improvisations, some even hand-to-hand. Then the new weapons arrived.

No one, least of all the troops, had expected such an artificially circumscribed conflict to go on long. But gradually the Weird War had developed a terrible symmetry, with written and unwritten rules, and a brand of ferocity all its own. It was non-lethal, but it was anything but harmless. Troops died from accidents, falls, disease. They could not be machine-gunned or bombed, but they could be blinded with lasers, stunned with high explosives, blistered with microwaves, driven insane with hallucinogens, and captured. In some ways the capture was worse. The U.S. treated its prisoners of war reasonably well, hoping for deserters. Russia treated its badly. It treated everyone badly. It did not want deserters. They had to be fed. It wanted Ukraine.

Some said it was like war had always been.

Loftis paused by an exposed boulder. The air was quiet and cool. He looked carefully around. Something menaced him, but he did not know yet what it was. He lifted his weapon and checked it, just as he had ten thousand times in six months.

In its way, the weapon he carried was the Sneekle War in microcosm: an expensive blend of humanitarianism, violence, and high technology that resulted in something on the very border of rationality.

The M22 P-gun had been adapted from the air guns used in wargames in the States. About the size of an M4, it fired not bullets but a hollow springloaded pellet. When this projectile hit cloth or flesh it injected a soporific agent. Almost instantly, it sent a man into eighteen to twenty hours of unconsciousness. Only if he were hit by three or more rounds did the dose become dangerous. The M22, like its Russian counterpart the AKPD, had a range of two hundred yards. It could empty a fifteen round magazine in two seconds. Its AI-enabled sight did not require careful aiming, but triggered the weapon as soon as it was on a target that radiated in the infrared.

He saw something move in the foliage ahead, stiffened, then recognized Oleksa. He and Branch were on point, scouting an open patch. Beyond it was the blue haze of sky. He was staring up at it, his lips framing the curse infantry on both sides greeted open sky with in this war, when he heard a far off thud.

Fifteen seconds later the forest burst apart.

Loftis had heard the downward screams. He was already burrowing into the ground beside a fallen log, the Russian on the far side, when the first shockshell went off.

The planet slammed up at him and then down. Gasping, he scrabbled at dirt. The explosions seemed to be inside his head, a detonation in his brain. White flares went off behind his squeezed lids. The foliage rustled to the flight of fragments. They were harmless. Light plastic. All you had to worry about was concussion, but it was enough. Non-lethal, but men blacked out from it, went into fits with jolted brains, went mad. It was generally combined with a more subtle form of attack. When the sky banged like subway doors opening he stopped burrowing and cinched mask and hood tight as he could pull them.

Close to his eyes, just beyond the fogging windows of the mask, the log was rotting. He was so close he could watch ants marching up from the interior, each carrying a grain of something he did not care to identify. They moved in steady files across the spongy bark. He raised his head a few centimeters and saw Agayants’ rump, the back of his pack. Good chance, he thought distantly, to see whose gear is better, theirs or ours. Could be useful intel . . . if they made it back.

A mist was creeping through the trees, finer than fog, all but invisible. “Stankey! You tight?” he shouted, not trusting squadtalk so close to the ground.

“Yea, Sarge.”

He roared for the others, but they were out of range of his voice. He pulled his hood tighter and made sure the velcro on his gloves held them close as a second skin.

The mist drifted down. He lay motionless, breathing shallow, eyes fixed.

He was watching the ants.

Their narrow files had begun to shatter. From obedient robots, highway followers across the rough surface of the log, they began to wander. Individuals weaved off from the collective. The stream itself meandered, reformed. The mist drifted down.

The ants boiled in every direction, antennae writhing. The disciplined mechanism of the nest was gone. They darted about, colliding, fighting. At last, one by one and then by dozens, they fell from the log into the mold below.

Six more shells thudded above the treetops, then another dozen, farther off. Then a rolling barrage, scattered all across the saddle between the two hills. A dud plowed through the trees, sending up a spout of dirt and pine needles.

“Up,” screamed Loftis through the mask.

He got to his knees. They felt weak. Then to his feet. He pulled the Russian along. Then, unaccountably, found himself pausing. He stared upward, at the moving leaves.

The sun, blazing through the swaying interstices, was shattering into a million subprimary colors. He swung his gaze to find Oleksa and Branch watching him. Their faces were melting. As he lifted his arm he saw it move in slow instantaneous frames, up stop, up stop, outlined in the terrific color.

“Run!” he shouted, the words turning to glue in his mouth. He began to stumble forward.

The forest around him began to deliquesce. It dissolved into light, into sound, slowly, like diamond melting in the terrific heat of a focused laser. The crunch of leaves under his boots shuddered up his legs like breaking bone. The sigh of wind whined like a lumbermill full of bandsaws. The edge of his mask was a scalpel at his neck.

He ran, panting, sobbing, sucking air. None came. The filter must be going. He was breathing the colorless gas, the psychokinesthenic. He felt something haul him backward, and crashed to the ground. Attack, he thought, pawing clumsily at his rifle. A double bombardment meant attack.

The flash of black was instantaneous, a glimpse through a gap of brush across the ravine. But he was already on his belly, his weapon already tracking in the same direction. He blinked back colors, waiting –

The p-gun pinged, jolting against his shoulder, pinged again. A crash came from the far side of the gully. Something buzzed above him and whacked into a tree.

Ahead boots pounded across the leafy floor. He swung and almost fired before he recognized camouflage. Stankey slid beside him like a thief into home, and peered over his sights into the tree line. “Shee-it,” he muttered though the mask. “Sure is hot in these body bags.”

The words melted through his brain. He tried to funnel thought to his lips. “Where’s . .. Oleksa?”

“Old Dad’ll be comin’ right along.” The private lowered his cheek to the stock, selected manual, and fired four rapid rounds into a patch of bush. Branches whipped, but Loftis saw nothing else. A moment later the short man trotted through the trees and joined them.

Loftis sucked air, sucked air. His head was clearing. I didn’t take much, he thought. A microgram through some exposed hairline of skin, some badly sealed seam of the suit. Not enough to truly drive him insane.

He was sweating now, and not only from the growing heat of the closed-up gear. He’d seen troops lying rigid, catatonic, after PK attacks. Their staring eyes told of the horror that gnawed through the framework of their minds, bringing them crashing down. Sometimes it lasted for hours, sometimes for weeks. And for some, for ever. It was a terrible weapon.

But it did not kill….

The bushes in front of them parted, and six men charged out. “Front!” he shouted hoarsely.

Three rifles pinged and bucked. Glass whipped through the air, kicked up leaves, whocked into tree boles. He ejected a magazine, slapped in a new one, fired as fast as the AI could pick up a target. The running men seemed to collapse. One threw his hands skyward, another half-reached for his belt before his rifle dropped from relaxing fingers and he crumpled to the ground.

Loftis’s ears were ringing from the shells. He shook the earset out and heard distant shouts. He stared around, blinking to clear the last polychrome fringes from his vision. Take the high ground…the ravine rose steeply to their right. There, nearer the top of the hill, they could move in several directions. But could they get up it?

There was no choice. Even as he concluded the thought he heard the striker click on an empty chamber. He jumped to his feet. “Stankey! Rear guard. Ten minutes, then uphill to right. Oorah.”

“Oorah.”

Magazines in the air: Oleksa and Branch’s, flung to the younger man as they backpedaled toward Loftis. Joynes was behind him. He turned and ran for the near-sheer wall, slinging his rifle. Halfway up, then he’d cover as Stankey fell back. He was twenty yards up rock and scree when he heard Joynes. “What?” he snarled, not looking back.

“Hand, Sargeant!”

He turned. The corpsman, face reddened with effort, was trying to push the Russian up the slope. Agayants, his face white behind his eyepieces, was struggling upward.

Loftis stared. His hand came slowly free of the rocky soil of Ukraine, and reached down. It gripped the glove of the soldier in black, paused, and then drew upward. The struggling body came after it, lifted almost effortlessly against gravity up the side of the hill.

“Stankey! Fall back!” the bull roar reverberated from the trees. “We’re hauling ass out of this shitstorm. Fall back on me. I’ll cover!”

Ahead of them stretched the forest, unbroken, untenanted yet hostile, still and yet dangerous under the eyes, like those of hawks, that searched their prey out from above.

The sky came to him black, the trees as black on black. He rolled on the crackle of pine branches, and spat the foulness of too-short sleep onto dark ground. “Jack,” he said softly.

“Here, Olin.”

“Time is it?”

“Twenty-three hundred.”

“Already? Jesus.”

The darkness stirred. The squad rolled out softly, muttering, yet careful not to drop rifle butts or even boots too abruptly. There had been drones just after nightfall, and there could be sonic sensors within hearing distance. Now, in the darkness, under tree cover, there was a little time when men could relax as soldiers always had. A rattle of water came from somewhere near. Loftis got to his feet, feeling every muscle in his body tighten against the movement.

“Stankey?”

“Here.”

“Branch? You doin’ okay?”

“Yo.”

“Doc?”

“Still here, goddamn it. Wakeup tabs, come an’ get ’em.”

“You – Agayants. You awake?”

“I hear.”

“Okay, listen up.” Loftis’s whisper was hoarse. “We made I figure five, six klicks good yesterday. Them chasin’ us back up the ridge lost us some. Need to make time tonight. But we got to be careful. Get it?”

The men muttered. One voice spoke clearly, though it was held low. “Yeah, Sarge. ‘Cepting for one thing.”

“Yeah, Stankey?”

“The Russki. We’re beat to shit, and we got to haul him too. I don’t get it. Why the fuck we carrying him for? I mean, we ain’t on recce, askin’ for prisoners. We’re running for our asses.”

There was a murmur from the others, half in protest, half assent. The Russian said nothing.

“I ain’t used to having my orders second guessed by no fuckin’ prives, son.”

“Sorry about that, Sergeant. But we out here in the wilderness. We got to get back, or we’re cold meat. Why we draggin’ him? I just want to know.”

“I think the sergeant – “

“Forget it, Doc. I’ll explain it to the slow learner here. Listen, Stankey. How long you been in this here war?”

“Six weeks.”

“How many wounded you seen?”

“He’s first one.”

“That mean anything to you?”

“Sure. The whole war’s Sneekle – nobody supposed to get shot like that. But so what? We didn’t shoot him.”

“Can you prove that?”

“Uh….no.”

“What happens to us if we did?”

Pause. “They shoot us.”

“Who?”

“The umps.”

“What else?”

“After they shoot us? You got me. The Corps issues us halos?”

He didn’t like the tone, but he ignored it, glancing at the dim digits of his tablet. You had to let them bitch, but he wanted to wrap this up. “After they shoot us, the other side gets a propaganda bonus. Allies violating Sneekle Treaty. Addicted to violence. Losing ground, so we’re starting to kill. Know what happens next?”

“Tell me, Sarge.”

“This war’s been seesawing for six months. The other side wants this country. They want to win. Oldstyle war, hate to say it, but they probably would. Something like this could give them the excuse to go conventional. We’re already on the defensive. We start taking casualties, without real guns in our hands, and the J Line’ll crack so quick Chosin Reservoir will look like a victory.”

“The sarge is right.” Oleksa’s voice. “I figure they got their old weapons in rear echelon, ready to come up overnight. All they need is an excuse – and finding this guy, with what I bet is a six-eight NATO-caliber bullet in him, is a dead setup for them. Sergeant’s right. We got to get back with him, or find an umpire, before they get us, or we’re fried.”

“Come on,” said Joynes. “You’re assuming – “

“That’s enough,” Loftis’ growl broke in. “On your feet. We got six hours of dark to travel in. Doc.”

“Yes?”

“Slowcoke. One dose each. We’ll be humping it. And Stankey – “

“Yeah?”

“You help our friend march.”

There was no reply, but he did not like the feeling of the stillness. A hand found his in the darkness, and he backhanded the pill into his mouth.

“Let’s go.”

The night march. Their BattleGlasses had had IR once, but when battery power fell the illuminators were the first to go. They moved as silently as they could, but time after time the ground dropped away in the dark and they fell, slid, cursed, dropped their weapons to clatter over rock. Or else it rose, and they had to claw their way up through gravel and scrub brush by feel, tearing their fingernails and the skin of their faces. The drug helped, much at first, less as the hours went by. He debated another dose, but decided against it. The time-release enhancers provided energy without a high, but there was a rebound; best to save it for the last dash to safety.

At five the sky grayed. He called a chow break. They sat, too weary to talk. Doc stared at the ground, Stankey cupped a vape, Branch sucked at her canteen. Only Loftis and Oleksa broke out rations and sat chewing moodily.

The Russian limped over to Loftis. “You give?” he said, motioning to the food.

“Sure, if you can stomach ’em. Course, yours might be even worse.”

“No caviar for the troops, I bet,” said Joynes, staring at him.

“Keep that vaper covered,” said Loftis.

“Understand. Sputniki.”

“What?”

“Satellites, he said.”

“Oh. Sputniks, huh? I get it.”

“Come on, Doc,” said Loftis, getting up. “Let’s recce.”

He and Joynes moved forward cautiously. The faint predawn made it easier to travel, but also more dangerous. A few hundred yards farther on the forest ended. Beneath their feet the ground softened, sucking at their boots.

“Swampy,” said the corpsman. “You got any rivers on your tablet?”

“Small one. Feeds into the Dnieper. We made good time if this is it.”

“Think we can get across before full daylight?”

“Sure like to try. I feel naked out here.”

“Think they know we’re here?”

“I don’t know. If that was a sensor drop last night…that rock probably carries sound pretty good. They might.”

When he stopped whispering there was a silence. He was turning to go back when Joynes muttered, “Sarge, tell me something.”

“What?”

“What are we doing out here, anyway? What’s this goddamn war for?”

He peered at the corpsman’s face. “We’re here to defend Ukraine. Don’t that make sense?”

“I guess. I just – I just hoped, once, for something more to fight for than the big-power skirmishing.”

“Politics ain’t my business. Or yours.”

“It ought to be.”

“Goddamnit, Doc, I don’t have time to argue.”

“All right,” said Joynes. “Forget it, Sarge. We’ll talk about it some other time.”

“Sure,” said Loftis. “Let’s go back now.”

The squad straggled forward in the growing light. The stark traceries of the forest fell back. No one spoke, not even when they came out on the bank and looked over the fog-shrouded river. They stood and stared. Branch knelt to rinse her face.

“How wide you figure?” Stankey muttered.

“Couple hundred yards.”

“Deep?”

“Higher than a man, for sure. Look how calm it is.”

“You two, left. I’ll go right. Look for a ford, or rapids.”

Oleksa found the boat three hundred meters upstream. They shambled up to it. Someone had staked it to a fallen tree on the shingle, and it lay now in weeds. Its quarter had been gnawed by decay. Loftis rubbed his chin. “Think it’ll float?” he muttered, to no one in particular.

“It’ll float.” Branch squatted by the stern, dug her Ka-bar into rotten wood.

“You know boats, Boot Camp?”

“Built one and paddled it all over Lake George when I was twelve. This here punt’ll leak, but we can hang on and bail till we’re across. I can fix it enough so two guys could sit in it and not get wet.”

“Terrific. Take charge of that. Rest of you, spread out. Look for something to paddle with.”

The sun was above the hills when Branch pronounced herself satisfied. She’d reinforced the rotten section with cut saplings and stretched a cammie shirt over them. Loftis hung back, willing to follow instead of lead for a few minutes more. The Marines grasped the gunwales and hustled the punt down to the shore. It settled into the river with the unenthusiastic air of a corpse revived by necromancy. Water began rising in bottom. Branch leaped in and settled herself on a thwart, then bent to scoop out the first helmetful. “Let’s go, there, Ivan,” she said sharply to Agayants. “Sarge, you coming?”

Loftis stood by the side of the river, screened by brush. They beckoned him, eyes alight, like kids. He thought of Huck Finn and Jim on the raft. He’d liked that book. The river smelled like a basement after a long winter. He looked upward. No cloud. His skin crawled at the thought of crossing open water in daylight. The drones circled higher than human sight, long-winged hawks that never came down. Swift killers with digital minds. The troops saw only thin contrails, like the trace of skates on a frozen pond, to mark those battles. But there were rumors of other machines that were only too happy to hunt man….

“Goddamn,” said Loftis, plunging into the river with the rest. They piled their p-guns in the bow and splashed outward, holding to the sides of the boat. “You might make a fucking Marine after all, Branch.”

The ground dropped under their feet. He was glad they hadn’t tried to swim, tired as they were. The river was cold and the current swift under the smooth surface, dragging them along with silent power. “Start paddling,” he grunted, glancing past Branch’s head at the open sky. He sculled with one hand, clinging to rough wood with the other. The shore began to recede as they stabbed at the river with scraps of driftwood. Branch bailed steadily over the stern.

“Eyes!” shouted Joynes.

They ducked, but there was no cover. The boat rocked, unbuoyant, unsteady. Loftis’s head jerked up. The soarer was too high to see, but its daughter drone wasn’t. It glided in fifty feet above the river, not much bigger than an owl. Sunlight glinted off a lens.

“Rifles!” he screamed. “Shoot that fucker down! Right now!”

Branch and Stankey had their M22s up in a moment. The RPV was faster. Its nose lifted and it buzzed past their heads, rocking to throw off their aim. Loftis caught the camera pod below the wing as it banked for another pass. “It ain’t marked,” Branch said tentatively, following it with his sights.

“Kill it, I said!”

Both rifles cracked. The vehicle’s engine jumped to a higher note. Branch fired again. It yawed and wove like a swallow, working steadily closer. Its propellers were blurs against the green of the hills. It dipped and came on, aiming like a hawk now, only five or six feet above the water.

“Gaz yest!”

The Russian grabbed for his mask. Loftis saw it at the same instant. A blue mist, swirling in the turbulence behind it.

“Gas!”

They snatched for their masks. Loftis found his under water, but the flap eluded his hand. The Eye buzzed toward them, the wasp whine of the engine filling the river. The Russian snapped his last strap into place. Branch was still firing. She hadn’t registered the PK at all. Oleksa had his mask half on. Stankey was groping for his.

It flashed over them. The whorls of mist, fading toward invisibility at the edges, drifted down onto the river.

“Shit,” muttered Loftis. He let go of his mask and heaved himself up on the gunwale, and then down. Branch’s face turned toward him, white and horrified.

They went over. The Russian screamed as he hit the river. Loftis remembered his wound. He ducked, found what he judged to be Stankey. His reaching hand could not find Branch. He swam downward, ignoring the struggles of the man whose uniform he held. His lungs ached, but he ignored them. His eyes began to burn and the kicking grew more fierce and then weaker. His outstretched hand found bottom. Rock and mud, sweeping by at the speed of current. It was cold down here, cold as death and winter. Stars exploded behind his eyes. He could stand it no longer. A scream tore from his open mouth, clothed in bubbles. He kicked downward.

An hour later they fought through thorns sharp as barbed wire. They tore at uniforms and skin. The ground was rocky, then soft. A grown-over field of stunted apple trees. Windfall squished under their boots, filling the close air with sweet decay.

“Uphill,” Loftis gasped. He seized the man nearest him and thrust him ahead with all his remaining strength. “Uphill!”

Stankey spun away, boots digging into the yielding ground. Jack Oleksa and Doc Joynes were coming up through the trees. The sun slanted behind them. The Russian was panting, his mouth a hard O. His arm was around Joynes’s neck. “What’s the hurry?” said the corpsman. His face was streaked with sweat and mud and blood. A p-gun was slung over his shoulder. Loftis caught that, then noted a bare spot on the corpsman’s cammies.

“That thing was waiting for us. Patrolling up and down the river. They know we’re here and that we’ve got – him.” He nodded at Agayants. “Figure we’ll have visitors soon, a blocking maneuver to our front.”

“We should be getting close to our own lines,” Oleksa managed between gasps. His face was gray to the younger mens’ white.

Shit, Loftis thought. His own mind was going hazy. He’d saved Stankey by sheer will. They’d almost drowned, but when they broke surface again the psygas had been driven downwind and the Eye was gone. Oleksa and the Russian had donned masks in time. Joynes had used his head, staying under the overturned skiff and breathing trapped air till the gas dispersed.

No one had seen Branch after the capsize. Loftis had waited as long as he dared, sending the men to search the banks downstream for a body. Nothing. The replacement had gone like so many others in this retreat, walked away into the fog of war.

It would have a bad effect on the rest. Four left. And one prisoner. Nine kilometers to NATO lines – if they hadn’t retreated farther in the last twenty-four hours.

“Helos,” came Stankey’s shout, a moment before the roar of the engines reached the others.

The aircraft roared in ahead of them, to their right. Through the trees he could see flashes of silver. “Troop carriers,” he said to Oleksa, who nodded silently. “Right flank, and ahead.”

“Let’s break left fast.”

“High ground?”

“Yeah. No…which way are our lines?”

Loftis sighted with the tablet, then pointed to a distant bluff. “That way. But if the line’s still there, anyplace we hit it will be good.”

“That’s it then.” hey looked at Agayants.

“You are going?”

“Fast as we can. You got to keep up.”

“I will try.”

They lay at the edge of the bluff, beneath the ragged leaves of ferns. Water trickled somewhere. Loftis felt it cold underneath him. He searched the ground. Yes, a spring. Muddy water welled up where he lifted the heel of his hand. He sucked the tiny puddle dry, then raised his head an inch. The ferns nodded in stillness. Each nod, each whisper of the still forest below drew his utmost attention, yet without distracting him from the overall situation. The heightened alertness came from within, partly, but it was also chemical: he’d asked Joynes for a CE enhancer.

The puddle had refilled itself. He lowered his head and drank again, slurping the muddy stuff between dry lips. Fill canteens if we have time, he thought. But no noise. No noise at all.

The enemy was all around.

He checked his weapon, seating the magazine, switching it on and off guidance. He remembered when rifles were all-manual, when a shot had to be aimed precisely to hit. Just like the Civil War. Now, with GUID selected, the AI made every boot a sharpshooter. You aimed as best you could, then pulled the trigger. When the waver of your muzzle caught man, when the sensor said something warm existed in the bowed timespace your pellet would describe, it completed the circuit. Your rifle jolted, and an enemy felt the whiplash sting of sleepytime.

The technology of centuries. He watched the heelprint refill with water, and bent again. All employed in the cause of war. Sometimes, like the corpsman, he found himself wondering about it, whether it was worth all he had seen and endured.

Something crackled in his earset. He became attentive, concentrating to hear through the steady whine of jamming. It was Joynes.

“…Just ahead.”

He lifted his head warily. The lasers could blind a man for life. And you couldn’t see them until they hit you, unless you caught their flash against foliage.

Somewhere in the leafy distance a weapon fired. Full automatic. The burst sounded strange. Loud. He frowned and pushed himself up a bit more. The Doc said something on the channel, but he couldn’t make it out through the whine. He glanced to his left, to where the Russian lay on his back, staring at the trees. If I feel helpless, how must he feel?

But he had no time to feel. He had only two choices. Fight and try to escape. Or find an umpire, and “surrender in UN presence.”

He decided to surrender the moment he saw a white helmet.

The firing broke out again, louder. It was to his left, in a thicker copse he could see from the edge of the bluff. Joynes was at their edge, with a rifle this time.

Suddenly he stiffened. The familiar popping of an M22. Only it sounded muffled, weak. What was going on?

Five soldiers appeared under the trees. They wore black stocking caps and black uniforms. They crouched, then sprinted between cover in short rushes. Loftis lined up his weapon. He selected guidance and set in a drop correction. When the next one broke cover he swung and fired. The man clapped his hand to his arm, dropping his weapon. He shouted something. The others turned to look. He started to point, but halfway up his arm became unsteady. He sagged. His head went back and his cap fell off. He disappeared.

The lead soldier waved in his direction. Loftis saw their barrels come up. He fired again, but before he could see a hit their muzzles flashed.

The ferns above his head snapped and flew apart. Something smacked the bluff edge, spraying his face with water and mud. The bullets hissed overhead.

Bullets.

The enemy was no longer playing sneekle.

He slid back, heart jumping. He caught a glimpse of the leader, on his knees, head sagging. He’d hit him. Agayants was looking at him. “Get moving,” he said in a low voice. He keyed squadtalk. “Loftis. They’re shooting live ammo. Two-round bursts. AN-94s, sounds like. Fall back. Any you guys see white?”

“No umps.”

“Nothin’, sarge.”

“Joynes?”

Christ, he thought. Of course there would be no umps. Not if the Russkis felt free to use live fire. He waited. The corpsman didn’t answer. “Joynes!” he shouted to the trees.

“Get going, jarheads.” It was the Doc, in a whisper. “Hit. You dudes move out.”

Loftis felt a blaze of rage. He jumped to his feet, bracing his body against the trunk of an elm. His maneuver caught the men below by surprise, out of cover. They stared up openmouthed. Trigger pressed, he panned the sight over them, correcting as the muzzle jerked at each exiting injector. Two Russians fell but more were appearing every moment, at least a dozen, running out from cover toward the bluff, then pausing to aim up at him. Return fire whacked into the trunk, and then, stunning him from fingertips to jaw, into bone below his elbow.

He blinked, thinking for a moment that the flash was from a laser. It wasn’t. He saw his rifle on the ground and tried to pick it up. His arm did not respond.

There was a rustle behind him and someone moved past, picking up the rifle, pulling him back from the bluff edge. “Shee-it,” it said. “Stopped one with your arm, huh, sarge? Careless. Come on, let’s retrograde.”

“Doc’s down there.”

“You heard his transmit. We can’t help. Let’s boogie.”

He came out of shock a little. Stankey was right. There were too many enemy. Agayants was ahead of them, pulling something from his pack. Tourniquet. Battle bandage. They were cotton, not plastiflesh like U.S. issue.

Oleksa crawled up. “You hit, Olin?”

“Yeah.”

“Doc?”

“Got to leave him.”

“Orders?”

“Lay smoke. Lay smoke.”

Oleksa loped off, head questing from side to side. The dull pop of a grenade. Loftis turned his face to feel the wind. Yes, he was laying it proper. But it wouldn’t cover them for long.

The corporal came back between the trees. “Old culvert on south edge. Leads down from a spring. Probably a farmhouse down there somewhere.”

“Wide enough?”

“Hope so. C’mon, move out.”

The smoke was thick, choking, like walking the rim of a volcano. It moved with the wind and they moved with it, hearing voices behind them. Oleksa knelt. The mouth of the culvert was hidden by bushes. Stankey started to kick them apart, but the reservist stopped him. The small man went in first. After a moment his voice came up, hollow. “Clear…ah…no, dammit, it’s blocked. Water can get through, but I can’t.”

A heavy burst came from behind them, beyond the smoke. “We’re fucken trapped,” muttered Stankey, glancing at the Russian with a look at once wild and profoundly sympathetic, as if he recognized for the first time that the other was a man.

“Get in,” said Loftis.

“What?”

“Get in, I said!”

“They’ll shoot us in there!”

He shoved the private with his good arm. Agayants had already seen. He ducked into the brush-screened opening. His blue eyes searched their faces before the darkness swallowed them. Stankey cursed. He sat and dropped his legs in. Loftis bent, looking back. The shouts were louder. Through the smoke probed the beam of a laser. It swept from side to side above his head, made visible by the pall.

The smokes would cover them for a few more seconds. Then it would be luck, only luck. He was thinking this when the beam dipped unexpectedly and struck his eyes. He staggered, raising his arm and blinking. Patterns of light wheeled in front of him. He could see nothing beyond them.

He slid his rifle by feel into the bushes. He fell into a night of red fire, biting back a cry as his shattered arm hit crumbling stone.

He waited through the day, shivering in the icy water, falling from time to time into short terrifying dreams. The circle of sky was dark when he unbent, favoring his arm, and began to crawl upward. He went slowly, slowly. They could have left geosensors.

When he came out of the bushes, p-gun balanced in his left hand, he paused for a long time to listen. He still couldn’t see very well, but the red wheels had begun to fade. The wind sighed through dark trees. The trickle of the spring filled the night. The bluff was empty.

“Come on out,” he whispered.

They moved slowly down the slope. Loftis blinked up at the stars and turned a little to the right. Something buzzed mosquitolike above them, and they froze, rigid and unbreathing, each man shielding his bare face from the sky. The whine faded into the wind’s whistle. They moved forward again, easing their boots down into the grass. From time to time a distant explosion rumbled over the hills. No one spoke. Loftis’s arm was a lump of pain. He had no more drugs. Joynes had carried them all.

You, he thought. Oleksa. Stankey. The Russian. It’s night. Almost out of ammo. You’re hungry and wounded, but you’ve drunk all the spring water you’ll ever want in your life. You have till dawn, about 0500. You have six klicks to go.

They trudged through the night for a long time. From time to time he looked at his tablet, then at the stars. At half past midnight Stankey muttered something behind him.

“What’s that?”

“I been thinking.”

“You?”

“You been telling us all along the Russkis shot him,” Stankey muttered behind him, ignoring his sarcasm.

“What? Close up if you got to talk.”

The private moved up. His breath was warm in Loftis’ ear. “I got it figured. The Army shot him.”

“What you talking about, Stankey?”

“Talking about our friend. The possibilities. They must be other troops cut off ‘sides us. What if it was our side shot him – the Army, or the Polish – accident, or deliberate?”

“So what? We still got to get him back. Russians can still pin it on us, private.”

“If they can,” said Stankey, lowering his voice still more so that Oleksa, directly behind, could not overhear, “So can the umps.”

“What are you sayin’?”

“That if he got a bullet in him, won’t the reffs, when we get back, say we shot him?”

“Hell, they can tell what kind of weapon a slug came from.”

“If there’s one in him. What if there ain’t? He been hiking pretty strong for a man with a bullet in him.”

“Take a break,” whispered Loftis. “Pass it back.”

They sighed and let themselves slump against trees. Stankey sat beside him. Loftis’s gaze slid beyond him, to where the Russian was scratching at the soil with his hand. He heard a soft sound, and then the man pulled up his trousers and settled a few steps away.

“You don’t trust your own mother, Stankey.”

“Why should I? The bitch stole from me. He’ll find some way to give us away. We ought to dump him.”

“Shut up,” said Loftis. “Five minutes. Then we keep moving. We only got five more klicks.”

At daybreak they crouched at the edge of a valley, shivering in the morning chill. Light etched the trees. Loftis tried to raise his rifle. His hand shook too much. He passed it to Oleksa. “Take a look. What d’you see?”

The older man squinted through the sight, then turned it to higher magnification. “Troops,” he said at last.

“Ours?”

“I think so. Can’t see color so good yet.”

“We’ll wait,” said Loftis. “Till we know.”

“Think they’re ours?” said Stankey.

“They’re in the right place.”

“What you plan to do?”

“Let’s see…I lost my squadtalk. Have you — “

“Mine’s dead.”

“So’s mine. And he don’t have one.”

“Guess that’s out.”

“Suppose we just run, then. Make a break.”

“There’s got to be Russians around if this is the front line. “

“What if there is? We got no comms. We out of ammo. We just got to run.”

“What if our guys got autoguns set, or those shock mines?”

“Well, they can tell we’re U.S. even if we’re asleep.”

Loftis nodded. A great tiredness took him and he slumped back. His eyelids slid downward, as inevitably as avalanches.

He dreamed, there in the dawning, that he and Doc Joynes were sitting on a mountain together. It was west of DC, in the Blue Ridge, and there was a bottle between them. The Doc was sipping from it, and arguing, just like always. They were talking about the war, as if it had been over for years, for a long time. “So what did you think?” Joynes was saying. “That a war without violence would be kind? It was a step up from a trade war and a step down from conventional. Each side was as ruthless as it could get away with. Nothing had changed.”

“The grunts on the ground weren’t dying,” grunted Loftis.

“Tell that to the guys blinded by lasers,” the corpsman said. “The guys who never thought again because they got a PK megadose. Or froze to death while they were knocked out, that winter.”

“You’re too friggin’ clever.” Loftis, in his dream, stood up and looked around. The tops of the blue hills were level with his eyes. “You make it seem like it was no progress. Well, by Jesus, I believed in the crazy thing.”

“‘War contains so much folly, as well as wickedness, that much is to be hoped from the progress of reason; and if anything is to be hoped, every thing ought to be tried,'” said Joynes, his voice taunting, though he did not smile.

“Who said that?”

“Madison.” The Doc laughed then. “And war in his day – not half bad. I’ll bet we lost more people in a battle than they did.”

“I bet we didn’t,” said Loftis. “My pop was in Iraq and he told me about that hell. I’d rather have took a pellet and starved for a year in a gulag than spent the rest of my life like him. He didn’t have no legs. An IED. And he always told me, he was one of the lucky ones.”

“Loftis.”

It wasn’t the Doc. Loftis remembered now that he was dead, left behind. It was the Russian, Agayants. The light was brighter and he was squatting between him and the sun, with Stankey’s face dark behind him, hand on his knife.

“What?” he said.

“It’s light,” said Oleksa. He was peering through his rifle scope.

“Can you see?”

“It’s our guys.”

Loftis nodded.

“But there’s blackyboys moving between us and them. Looks like preps for an assault.”

Loftis nodded again. His arm throbbed with an insidious pain, as if something were eating its way inside it, next the bone, toward his heart.

“Loftis,” said the Russian again.

“What the hell you want, Wal-demeer?”

“I can help us to other side.”

“How?”

“Talk. I tell soldiers we shpionam – spy.” He looked earnestly at them.

“Jack?”

The corporal raised his eyebrows. “Weird, but it might work.”

“Leopold?”

“Don’t call me Leopold.”

“Okay, Private Stankey. What do you say?”

“I don’t trust him.”

Loftis looked at the anxious faces. “Wal-demeer – “

“Vladimir.”

“Everybody’s worried about his name today. Okay. Vla-di-meer. Now, Private Stankey still wants to know how you got shot. So do I. Sure you don’t have a better explanation than the last one we heard?”

“I shoot myself,” the Russian said.

“What?”

“I shoot myself with gun.”

The Marines stared at him. “You must have wanted out of the army pretty bad,” said Oleksa.

“Not out of army. Out of killing.”

“Come again.”

The Russian chewed his lip. He looked toward the hill opposite, then seemed to make a decision. Words tumbled out. “I know plan. One general make it. More, more attacks with bullets. No more ni viernaya voina – false war. They give us gun for bullet, not sleep. You see? So I go off, shoot me, so not to kill other. That, I do not believe to do.”

“Then we found you, instead of your own people.”

“Da.”

“What happens if they find you shot yourself?”

“Trial,” he said. “Prison, el’e death.”

“Jesus. Why didn’t you say so?”

“I thought” – he glanced at Stankey, who lowered his eyes — “You not take me back then. That you same as them.”

Loftis nodded. After a moment Oleksa did too. They faced forward. “Get back on that goddamn scope,” he told them, and lifted his own.

The other side of the valley; the top of the facing ridge. Through the glass it leapt up so clear and sharp he wondered if he could touch it. “You’ll help us get through?” he asked Agayants.

“Da. Then I talk to sud’ya. To UN.”

“Why?”

“I say, I do not like killing.”

“Well,” said Loftis, “Maybe there’s some kind of program for defectors. I mean, don’t seem like you should be a POW, after that.”

“I would rather be prisoner.”

“You mean that?”

“Yes,” said the Russian. He chewed on the tips of his fingers nervously. “I am not traitor. Just do not want to kill. This war bad, but not like old kind fighting. You know, Sovietsky Soyuz lose twenty, thirty million in Patriotic War. Never, never repeat. Maybe future be like this instead.”

Loftis turned his head. “Sounds like good sense, don’t it, Jack?”

“What’s that?”

“Sneekle War is hell – but it’s better than the real thing. ‘Cause maybe that’s the way things come in the world, you fight your way uphill a little bit at a time.”

“Maybe so,” said Oleksa. “Maybe so.”

“Doc wouldn’t have said so.”

“Sure he would. He just liked to argue.”

“Ready to cross?”

“Any time.”

“Brother?”

“On your ass, Olin.”

“Val-demeer?”

“I am ready.”

They grinned at one another. The growl of motors came from behind them. Over their heads, the leaves stirred in the first breath of morning wind.

Together, they walked down into the valley.

David Poyer is the most popular living author of American naval fiction. His military career included service in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, Arctic, Caribbean, the Middle East, the Pacific, and the Pentagon. His epic novel-cycle of the modern military includes The Med, The Gulf, The Circle, The Passage, Tomahawk, China Sea, Black Storm, The Command, The Threat, Korea Strait, The Weapon, The Crisis, The Towers, The Cruiser, Tipping Point, Onslaught , and Hunter Killer (all available from St. Martin’s Press in hardcover, paper and ebook formats). Deep War, the latest in his War with China series, will be published December 8. Visit him at www.poyer.com or on Facebook.

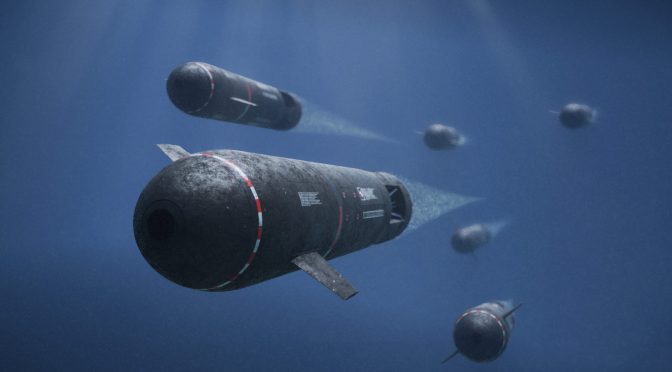

Featured Image: “The Hunt” by Reha Sakar