By Mie Augier and Sean F. X. Barrett

Introduction

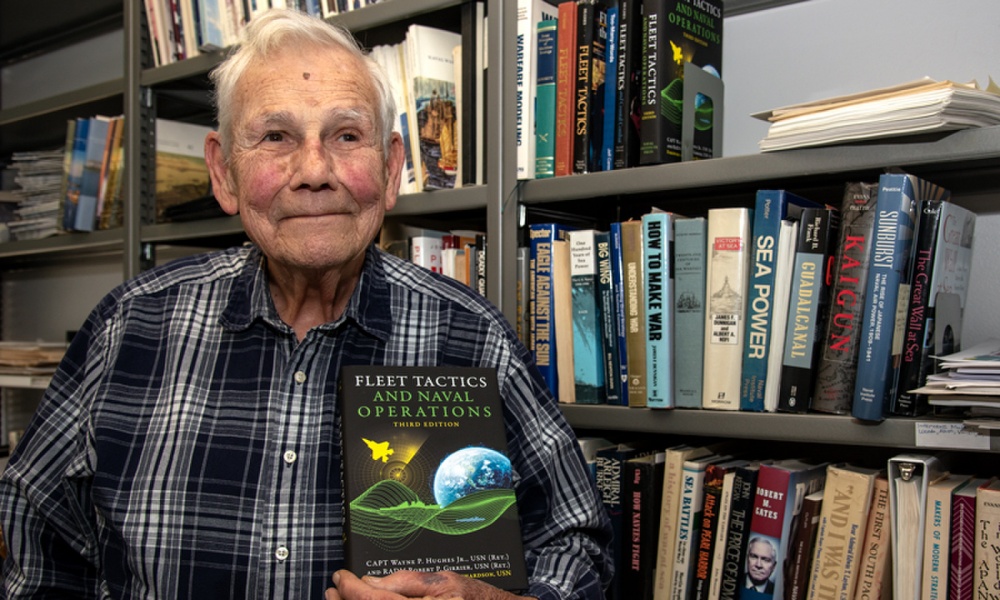

Captain Wayne Hughes, USN, who would have turned 90-years-old this spring, left us a huge legacy on which to build and from which to learn regarding the intellectual content of naval research, our approaches to instruction, and how we organize our naval PME institutions. Hughes is widely recognized and respected for his work on naval tactics and operations research (OR) and his “fire effectively first” aphorism, which continues to inform the thinking behind many strategic documents.1

If we take a more expansive look at Hughes’ contributions, however, we also find writings on naval maneuver warfare,2 the influence of organizations on naval tactics,3 the limitations of analytical models and their ability to reduce risk but not eliminate uncertainty,4 education and mentorship,5 his favorite admirals,6 maritime innovation and shipbuilding adaptation,7 the need for innovative leaders and the role of PME in educating them, and the importance of people, among other topics. Concerning the range of his own intellectual interests, he noted, “I like everything, but that means I can’t be very deep at anything.”8 Though he did obviously go deep into key topics, he maintained his broad interest, which also manifested itself in the variety of books he reviewed and his touching upon some unexpected topics, such as rituals and religion,9 in the context of naval warfare. His intellectual, theoretical, disciplinary, and methodological range exemplified that of an integrative mind.

In addition to his research and writing, he advised countless students at the Naval Postgraduate School and often eagerly visited classrooms, even in his last years, to discuss some of his favorite topics, as well as what interested the students. He favored active learning approaches (e.g., cases, discussions, gaming, and simulations as opposed to lecturing) since they facilitated more interaction, mutual learning, and a continuing integration of conceptual frameworks, instructor and student interests, and naval issues. Hughes’ approach to active learning is quite consistent with General David H. Berger’s plea in his Commandant’s Planning Guidance to move beyond our industrial age model for training and education. C. S. Lewis once said, “The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts.”10 In other words, cultivating lifelong learning requires patience, mutual learning, and open minds – a topic that remains central to military professionals today.

We wanted to write a brief note in Hughes’ honor and memory that complements and expands upon his “fire effectively first” lens by incorporating the importance of the “think effectively first” truism it implies.11 We use some of Hughes’ reflections to identify the traits, attitudes, and values he admired in others and thought we should strive to inculcate in our naval leaders. Just as integration is key to instruction and active learning approaches, intellectual integration and synthesis helps develop the good thinking and judgment that enables our warfighters to develop the intellectual adaptiveness central to “thinking effectively first.”

The Skills and Traits of Hughes’ Favorite Admirals

During the spring of 2017, Thomas Ricks posted a series of four articles to his Best Defense blog that Hughes—“an old salt”—had written about his four favorite admirals: Spruance, Burke, Fiske, and Nimitz. They illustrate both Hughes’ implicit (and sometimes explicit) recognition of the attitudes and skills central to “thinking effectively first,” and his own integrative way of thinking.

As a youthful teacher of naval history, Hughes first gained an early appreciation for Raymond Spruance while reading about his meeting with Admiral Nimitz before the Battle of Midway. Hughes identified Spruance’s background in electrical engineering and his operational and command tours as a few of the foundations for Spruance’s greatness since they provided him a broad range of experiences and insights upon which to draw and enhanced his ability to integrate and synthesize information.12 This helped him identify what was truly relevant and deepened his understanding of situations. In an earlier article on Spruance, Hughes noted, “As operational commander of hundreds of ships and aircraft, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance had the capacity to distill what he observed – and sometimes felt – into its essence and to focus on the important details by mental synthesis.” According to Hughes, “Spruance had to an extraordinary degree the mental equivalent of peripheral vision.”13 Importantly, Spruance objected to efforts intended to reduce decision-making to a recipe or checklist. As Spruance might have attested, developing the “cognitive flexibility” to transfer knowledge between domains and apply knowledge to new situations necessitates education focused more on broad concepts than on specific information or processes. Additionally, given the complexity of and unpredictability in today’s operating environment, it is increasingly important to nurture well-rounded naval leaders like Spruance who are able to identify connections across disciplines so they can effectively determine the deep structure of a given problem, understand the larger forces shaping situations, and thus anticipate possible outcomes and actions.14

Like Spruance, Admiral Arleigh Burke also had an impressive technical background that led to his serving more tours as an engineer than he might have liked. Burke was an excellent strategic leader who created an effective organization by understanding how organizations work and how to get things done in (and with) them. According to Hughes, “He was the last CNO to actually command the Navy’s operations.”15 In other words, Burke did not become mired in administrivia as an escape or diversion as the Navy confronted a strategic inflection point. Instead, he identified new opportunities and ways of operating and deployed resources to see them through.16 This is particularly relevant for the U.S. military, which has been described as “too busy to think” and operating in “a vacuum, one of strategy-free actions,” as it confronts interstate strategic competition following two decades of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations.17

Hughes dubbed Bradley A. Fiske a true “Renaissance Man.” A reformer, prolific author, and inventor, and an innovative strategist and tactician, Fiske helped lead the Navy through the transition from sail to steam. Early in his career, Fiske identified the need for electricity in the ships of the new Navy, so he requested a leave of absence to study its potential for warships. At the time there were not any postgraduate schools for science and technology, so he ended up at the GE plant in Schenectady, New York.18 Later, he became an aviation enthusiast and advocated using it in an anti-amphibious role in support of early versions of War Plan Orange.19 In his many roles, Fiske maintained a practical appreciation for technology as opposed to a narrow focus on analytical models or technical expertise, and based on his deep understanding of what was driving the strategic environment, he had an uncanny ability to identify emerging technologies and embrace them. In class, Hughes occasionally brought up Kodak as a counterexample. While Kodak had early technical expertise in digital technology, they failed to see how it would influence the strategic environment and, ultimately, erode their competitive advantages.

Lastly, like the others, Chester Nimitz also had a deep understanding of technology and its relation to tactics, a theme consistent with all of Hughes’ “greats.” Nimitz became an expert in diesel propulsion, remained current with both submarines and surface ships, and even wrote a Naval War College term paper on underway replenishment. He was not only an admired strategist, but also a superb tactician, which was on display at the Battle of Midway, and a brilliant leader. Hughes credits his morale-building after taking over as Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet following the Pearl Harbor attacks with our later success in the Pacific.20 And yet we might draw an important lesson from his time commanding a destroyer as an ensign when he ran the ship aground. The mistake did not end his career as it might today. As Hughes used to say, the only way to never make a mistake is to never make a decision, thus recognizing the danger of the no-default mentality on individual and organizational adaptability and thinking

Having briefly discussed Hughes’ reasons for choosing his favorite admirals, we note his appreciation of their knowledge of technology. However, this was not the only factor (and probably not even the most important one) when one looks at their accomplishments more broadly. Hughes valued judgment and thinking, the development of insight, broad understanding and the ability to synthesize, and organizational leadership skills. These are themes that resonate well with modern strategic documents, such as the Education for Seapower report and General David H. Berger’s Commandant’s Planning Guidance.

It also worth remembering that these qualities were valued much earlier in the history of naval education and during periods of vast technological change similar to our own. For example, The Record of the United States Naval Institute (later, Proceedings) established an annual prize essay competition in 1879, and the first topic concerned naval education. In the third-prize essay, then Commander A. T. Mahan cautioned, over a decade before the publication of his famous treatise, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660-1783, against focusing too narrowly on mechanical processes and mathematical reasoning “under the delusive cry of science.” Despite the increasing technical complexity associated with the ships of the new Navy and the onset of steam, Mahan observed, “The necessarily materialistic character of mechanical science tends rather to narrowness and low ideals.” He believed that a narrow scientific focus ultimately undermined the practical discharge of the line officer’s duties, and while Mahan acknowledged a small class of specialists should be devoted to this type of knowledge, he also argued the line officer required a broader educational approach in order to discharge all of his many and varied duties.21

Following World War I, the Knox-Pye-King Board conducted the first (and until E4S, only) comprehensive analysis of U.S. naval education. At the time, a salt-horse culture prevailed in the Navy, and seagoing experience established naval officers’ reputations for higher commands. The curriculum at the U.S. Naval Academy trained future naval officers to adopt mathematical approaches to solving even the most abstract problems, memorize accepted solutions, and adhere to hierarchical authority at the expense of open inquiry and debate. However, as Admirals Henry T. Mayo and William S. Sims provided bureaucratic top cover, Captains Dudley W. Knox and Ernest J. King, with Commander William S. Pye contributing, leveraged the board’s report to proffer their assessment that naval officers stood ill-equipped to meet the broad spectrum of challenges they faced and to establish higher professional education standards.22 While the officers acknowledged the need for a certain degree of specialization, it had to be balanced with a more generalist mindset. The board observed that, at present, the naval officer was “‘educated’ only in preparation for the lowest commissioned grade” and lacked sufficient understanding of higher operational elements of warfare or broader strategic considerations. The board outlined an education continuum for an officers’ career, which progressively evolved away from more technical matters and toward strategy, management, international relations, and economic, political, and social sciences.23

Given the increasing complexity and prevalence of technologies and their rapid rate of advancement, calls for increasing the number of specialists in the DoD and national security establishment are certainly understandable. However, as we observe in Hughes’ reflections and in the thoughts of some of our other great naval officers, we must not view this as a sufficient condition. We must also cultivate the other skills and attitudes Hughes valued to develop leaders who are intellectually adaptive and capable of identifying strategic trends, understanding and solving complex problems in an interdisciplinary manner, and thinking effectively first.

How to Cultivate the “Think Effectively First” Mentality

“I think art comes before science, and science is merely a representation of the dynamic structure and institutionalization of what the practical wisdom of people over the course of history develops.”24

While Hughes’ reflections are useful in helping us see the importance of “thinking effectively first,” it is also important to understand how Hughes was thinking (not just what he was thinking) and his way of integrating. In doing so, we might identify a few more useful implications that can help us better think about how we think, educate, learn, and analyze.

Integrate education, research, and Navy problems—always with an eye for issues relevant to the warfighter. As with other great integrative minds, Hughes was a strong advocate for integrating research and education, always with a focus on what was relevant to Navy problems and warfighter issues. This problem-oriented focus helps integrate the different disciplines that are relevant to understanding such complex problems, as they rarely, if ever, fit any one or two disciplines very neatly. This may sound straightforward, but it is not easy. Nobel laureate Herbert Simon (1967) noted that for professional education, mixing the disciplinary perspectives of the scientists with practical problems of the professionals is like mixing oil and water. The task is never finished since it requires constant stirring.25 Additionally, integration across disciplines does not come from one discipline talking occasionally to his favorite intellectual neighbor who holds a (mostly) similar worldview, but rather through genuine intellectual appreciation for other perspectives and what they can bring to improving our understanding of warfighter issues. Fortunately, our PME institutions can help with this by facilitating and encouraging (perhaps even insisting) more mixing and integration of different disciplines in their application to explicit warfighter problems.

Focusing on integration helps us understand the promises and the limitations of models and analysis. In understanding Hughes’ way of thinking and (re)reading his analytic work, we also gain a better appreciation for the promises and pitfalls of analysis.26 Hughes acknowledges that analysis can help us prepare for war and has previously helped us win wars and reduce their cost more than is appreciated. Models, however, cannot capture certain imponderables (e.g., willpower, genius, surprise) that can unpredictability swing the course of events and thus require prudence in their application. They can never replace military judgment. Hughes cautioned us:

“Personally, I think that analysts—the good ones—next only to historians, understand best the imponderables of the next war. But in the heat of our petty contentions to sell our service, or some hardware, or an idea, or a strategy, we play down and eventually forget our doubts and misgivings. When the analysis is elegant, when the arguments are compelling, when the model is elaborate, that is the time to remember a statement by our host VADM Jim Stockdale: ‘if there was anything that helped us get through those eight years (as POWs), it was plebe year, and if there was anything that screwed up that (Vietnam) war, it was computers.’”27

Finally, educating for integrative minds and thinking effectively first requires cultivating the right mental habits, including some of the following:

- Prioritize problem framing (and reframing) and actively seek alternative and opposing views to prove our own hypotheses incorrect.

- Think critically, constructively, and strategically, and about the process of thinking itself to improve our intellectual adaptability and be learners that are always eager to extend our knowledge, whether through reading, experimentation, debates, or otherwise.

- Encourage active open-mindedness and intuition, and inspire imagination and curiosity to inform judgment and integrate analytical, intuitive, and synthesizing ways of understanding Navy and warfighter problems.

Conclusion

We hope we have illustrated how the broader foundations and aspects of Hughes’ contributions are important for recognizing how the core of his approach was not a narrow focus on specific disciplines and models, but rather a larger appreciation of both the art and science of naval warfare. Additionally, his work on analysis and tactics – the key to “fighting effectively first” – might be usefully supplemented with an emphasis on “thinking effectively first.” The Joint Chiefs of Staff reminds us, “There is more to sustaining a competitive advantage than acquiring hardware; we must gain and sustain an intellectual overmatch as well.”28 While effective fighting requires mental rigor and stamina and a sound assessment of the enemy, the operating environment, and ourselves, we must cultivate effective thinking and judgement above all. Let us embrace this challenge in the spirit of Captain Wayne Hughes’ legacy.

Dr. Mie Augier is a Professor in the Graduate School of Defense Management at the Naval Postgraduate School and a Founding Member of the Naval Warfare Studies Institute (NWSI). She is interested in strategy, organizations, innovation, leadership, and how to educate strategic and innovative thinkers.

Major Sean F. X. Barrett is an active duty Marine Corps intelligence officer. He is currently the operations officer for the Headquarters Marine Corps Directorate of Analytics & Performance Optimization.

References

1. David H. Berger, Force Design 2030 (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 2020), 12; David H. Berger, “The Case for Change,” Marine Corps Gazette 104, no. 6 (Jun. 2020): 12.

2. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Maneuvering Past Maneuver Warfare,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 122, no. 5 (Mar. 1996): 16, 19; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Naval Maneuver Warfare,” Naval War College Review 50, no. 3 (Summer 1997): 25-49.

3. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Garbage Cans at Sea,” in Ambiguity and Command: Organizational Perspectives on Military Decision Making, eds. James G. March and Roger Weissinger-Baylon (Marshfield, MA: Pitman Publishing Inc., 1986), 249-257.

4. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Uncertainty in Combat,” Military Operations Research (Summer 1994): 45-57; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “What Studies Say—And Don’t,” Phalanx 12, no. 5 (Mar. 1980): 1, 12-15.

5. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “New Directions in Naval Academy Education,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 87, no. 5 (May 1960): 36-45; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Restore Mentorship Through Mentoring,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 2 (Feb. 2018): 76-77; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Naval Tactics Needed in Sea Power Education,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 11 (Nov. 2019): 12-13.

6. See, for example, Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Clear Purpose, Comprehensive Execution—Raymond Ames Spruance (1886-1969),” Naval War College Review 62, no. 4 (Autumn 2009): 117-130.

7. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “A Business Strategy for Shipbuilders,” (lecture, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, July 28, 2014), https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/63312/HughesMaritimeBusinessStrategy2014July28.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

8. Michael Garrambone, “Military Operations Research Society (MORS) Oral History Project Interview of Wayne P. Hughes, FS,” Military Operations Research 9, no. 4 (2004): 29-53.

9. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “Pacifists and Peacemakers,” Naval War College Review 27, no. 3 (May-Jun. 1974): 83-86; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., “On Ritual,” Phalanx 27, no. 1 (Mar. 1994): 35.

10. C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (Québec, ON: Samizdat University Press, 2014), 6.

11. While Hughes noted the importance of critical thinking, decentralization, delegation, enabling initiative, and judgment, he rarely expanded upon his reasoning or explained why they are so important to the continued nurturing of our naval leaders, perhaps because he was one of those rare individuals who naturally thought critically and constructively about things. For the rest of us, we can look to the recent literature on thinking and learning.

12. Wayne P. Hughes, “An Old Salt Picks His 4 Favorite American Admirals—And Explains Why (Part I),” Best Defense, August 11, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/08/11/an-old-salt-picks-his-4-favorite-american-admirals-and-explains-why-part-i-2/#. This piece originally ran on March 29, 2017.

13. Hughes, “Clear Purpose,” 117, 125.

14. David Epstein, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World (New York: Riverhead Books, 2019), 45, 50, 115.

15. Wayne P. Hughes, “An Old Salt Picks His 4 Favorite American Admirals—And Explains Why (II): Burke,” Best Defense, April 3, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/03/an-old-salt-picks-his-four-favorite-american-admirals-and-explains-why-ii-burke/. Hughes admired Burke’s tactical prowess, exploiting radar and torpedoes to our advantage in the Pacific. As a captain in the late 1940s, Burke had the gumption and technical acumen to serve as part of the brainpower behind the “Revolt of the Admirals,” and then as Chief of Naval Operations, he supported the development of the Polaris missile and SSBNs.

16. For more on identifying and navigating through strategic inflection points, see Andrew S. Grove, Only the Paranoid Survive: How to Exploit the Crisis Points That Challenge Every Company and Career (London: Profile Books, LTD, 1996), 101-164.

17. Robert H. Scales, “Too Busy To Learn,” Army History 76 (Summer 2010): 27-31; James N. Mattis, “Remarks by Secretary Mattis at the U.S. Naval War College Commencement, Newport, Rhode Island” (speech, Newport, RI, June 15, 2018), U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/1551954/remarks-by-secretary-mattis-at-the-us-naval-war-college-commencement-newport-rh/.

18. Wayne P. Hughes, “An Old Salt Picks His 4 Favorite American Admirals—And Explains Why (III): Fiske,” Best Defense, April 11, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/11/an-old-salt-picks-his-4-favorite-american-admirals-and-explains-why-iii-fiske/#.

19. John T. Kuehn, America’s First General Staff: A Short History of the Rise and Fall of the General Board of the Navy, 1900-1950 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017), 84-85. Fiske was also part of an insurgent group of reformers that believed the Navy was unprepared war and as a result pushed for a General Staff akin to the German model. Given the advancement in technology, the secretary of the Navy had too much control over constructing and operating the fleet and was out of his depth. Fiske eventually served as the Aide for Operations (and thus the number two man on the General Board) and was instrumental in pushing legislation through Congress that established the position of Chief of Naval of Operations and his supporting staff.

20. Wayne P. Hughes, “An Old Salt Picks His 4 Favorite American Admirals—And Explains Why (IV): Nimitz,” Best Defense, August 11, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/08/11/an-old-salt-picks-his-4-favorite-american-admirals-and-explains-why-iv-nimitz-2/#. This piece originally ran on April 18, 2017.

21. A. T. Mahan, “Naval Education,” The Record of the United States Naval Institute 5, no. 9 (1878-1879): 345-376.

22. David Kohnen, “Charting a New Course: The Knox-Pye-King Board and Naval Professional Education, 1919-1923,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 3 (Summer 2018): 121-141.

23. “Report and Recommendations of a Board Appointed by the Bureau of Navigation Regarding the Instruction and Training of Line Officers,” Proceedings 46, no 8 (Aug. 1920): 1265-1292.

24. Garrambone, “MORS,” 33.

25. Herbert A. Simon, “The Business School: A Problem in Organizational Design,” Journal of Management Studies 4, no. 1 (Feb. 1967): 1-16.

26. See, for example, Jeffrey E. Kline, Wayne P. Hughes, and Douglas A. L. Otte, “Campaign Analysis: An Introductory Review,” Military Operations Research Society (2011): 12, accessed June 21, 2020, https://mors.enoah.com/

27. Hughes, “What Studies Say,” 13-14.

28. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Developing Today’s Joint Officers for Tomorrow’s Ways of War: The Joint Chiefs of Staff Vision and Guidance for Professional Military Education & Talent Management (Washington, DC: May 2020), 2.

Featured Image: Retired Navy Captain Wayne P. Hughes, shown addressing the Naval Postgraduate School commencement in December 2011, emphasized the importance of studying tactics. (NPS photo)