Through the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, the authors have just published China Maritime Report No. 1, entitled “China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA.” In it, they propose a more formal term for China’s maritime militia: the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). The present article, the first in a three-part conclusion to their nine-part series on the PAFMM of Hainan Province, will instead use the term “maritime militia” to maintain consistency with all preceding installments and to facilitate discussion of China’s broader militia construction.

By Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson

Hainan Province’s unique geography makes its buildup of maritime militia units the spear tip of China’s prosecution of gray zone operations in the South China Sea: as a standing, front-line force whose leading units are lauded as models for other localities to emulate. This series has therefore examined Hainan’s leading maritime militia units, located in Sanya, Danzhou, Tanmen (in parts one and two), and Sansha. To understand these grassroots units and their development, it has delved deeply into their respective local environments. Having examined these leading entities in depth, it is time to take a province-wide look at larger policy processes and trends in implementation. This installment will also examine the intentions of China’s leaders to construct new elite militia units tailored to meet heightened requirements in China’s armed forces. This new type of front-line militia will serve as a standing force for more regular employment in support of China’s objectives at sea. Part 1 of this final series will therefore explore maritime militia building in a more systemic organizational context, chiefly at the Provincial Military District level; while Part 2 will address specific challenges and how they are managed. Part 3 will conclude this series by appraising the results of Hainan’s maritime militia construction effort and discussing some additional dynamics at play in the provinces. This first part will thus start by probing how a frontier province like Hainan responds to national level militia building initiatives and the measures taken by provincial leaders to oversee its implementation.

China’s national defense system is divided geographically into Theater Commands, previously termed Military Regions. Each Theater Command contains several Provincial Military Districts (MD), where the militia’s direct chain of command begins. As each province is divided into municipalities, each MD is divided into multiple Military Sub-districts (MSD); within each are numerous county-level and grassroots People’s Armed Forces Departments (PAFD). County-level PAFDs are staffed by active-duty personnel while the grassroots PAFDs are non-active duty organizations staffed by “full-time people’s armed forces cadres” (专职人民武装干部) who represent the direct interface between the militia and the PLA chain of command. Each MD oversees the militia work conducted by the MSDs and PAFDs within its area of responsibility.

Local governments provide funding and support while local military commands assume the bulk of responsibilities in maritime militia organization, training, and command. Government agencies such as the Maritime Safety Administration and the China Coast Guard (CCG) assist with aspects of maritime militia building pertaining to their bureaucratic functions, such as training in search and rescue and instruction on maritime law and regulations relevant to their operations.

The National Environment in Which Hainan Province and Its Militia Operate

Propelled by strategies and policies at the national and provincial levels, China’s Maritime Militia continues to grow and develop robustly. Many PLA and government leaders from all levels have some understanding or experience in building or working with the militia as an official component of China’s armed forces. Leaders from the top echelons of Central Military Commission (CMC), Party, and State leadership; as well as leaders of the PLA services, military regions, and provincial MDs; all attended the last National Militia Work Conference held in Beijing on 15 December 2011, a meeting to establish guidelines for nationwide militia work. President Xi Jinping himself likely became intimately familiar with the militia system during his career, particularly as the former deputy director of the Nanjing Military Region National Defense Mobilization Committee from 2000 to 2003. Overall militia policy is first set in Beijing and implemented through the principal civilian and military leaders of the provinces and counties via a dual leadership system of militia work (民兵工作双重领导制度). The militia itself represents an important personnel-centric line of effort in China’s Military-Civilian Fusion concept, recently elevated to a “national strategy.”

Ongoing PLA reforms mandate a reduction in militia personnel nationwide, continuing a trend of replacing outdated infantry militia units with technically capable militia more suited to supporting each of the PLA services in modern, informatized warfare. Maritime militia, meanwhile, are growing in proportion to their land-based counterparts as China prepares for “maritime military struggle,” as highlighted in its 2015 Defense White Paper. This seaward shift is materializing in national-level militia policy as well as in actual militia unit construction. Coastal cities like Shanghai and Beihai have all reported increased maritime militia growth. However, as China’s southernmost province tasked with administering all of Beijing’s maritime claims in the South China Sea, Hainan bears commensurately large expense for border and coastal defense militia construction.

PLA reforms have also modified management of the MD system by splitting the former General Staff Department (GSD) into several new departments, one of which is the new Central Military Commission-level National Defense Mobilization Department (CMC-NDMD). Already deemed to be in “post-transfer” (转隶后) status by China’s military press, the MD system is now managed by the CMC-NDMD, relieving Theater Commands of many administrative burdens, including the supervision of militia work in the provinces. Discussion in the PLA over the exact role of Theater Commands in the development of national defense mobilization capabilities appears to be ongoing, indicating that the exact relationship between Theater and MD commands in the building and management of reserves has yet to be clarified. Huang Xiangliang, director of the National Defense Reserve Force Department of the Nanjing Army Command College, explains how the PLA reforms strengthened “centralized strategic-level leadership over the nation’s militia and reserves” by directly connecting MDs to the CMC. As the reserves diversify to meet the demands of each PLA service, Huang elaborates, those “services will put forward their requirements for the reserves, which will then be organized, trained, and supported by each level of the MD system.” For the maritime militia, this will entail greater numbers of specialized units trained to support People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) operations.

Statements and policies guiding maritime militia construction are emerging from the CMC-NDMD. During a March 2016 interview, the newly promoted head of the CMC-NDMD Lieutenant General Sheng Bin confirmed the prominence afforded maritime militia building in the 13th Five Year Plan. China, he declared, will “adjust and optimize the scale, structure and layout of its militia and reserves, emphasizing construction of the maritime militia, coastal defense militia, emergency response militia, and new types of reserves.” Indeed, the Outline of the 13th Five Year Plan emphasizes strengthening the reserves and “maritime mobilization forces” in particular. On 28 July 2016, the head of the CMC-NDMD’s Militia and Reserves Department, Major General Wang Wenqing, also gave public guidance for solving common issues in maritime militia building.

Implementation is progressing apace. As CMC-NDMD Deputy Head Major General Hu Yishu describes in an October 2016 article in China’s Militia, a PLA Daily publication guiding national militia work, that revisions are underway on the nation’s Guidance Law for Maritime Militia and Border Defense Militia Military Training Work. This will regulate the tactics and training methods for “maritime militia participating in rights protection actions and support for PLAN actions.” With significant PLAN South Sea Fleet presence, the Hainan MD will likely see greater demand for maritime militia units configured to support PLAN operations in the South China Sea.

The Provincial Command

The Hainan MD’s military leadership published extensive articles in late 2015 comprehensively outlining missions, organization, training, and other aspects of Hainan’s maritime militia development and operations. The writings, by MD Political Commissar Major General Liu Xin and MD Commander Major General Zhang Jian respectively, appeared in National Defense, a domestically-oriented journal sponsored by the PLA Academy of Military Science. They reveal much about how the Hainan MD envisions and plans to execute national militia guidelines to help operationalize Beijing’s South China Sea strategy. Essential to directing a province’s construction of its maritime militia, such leaders directly promulgate militia construction requirements to their civilian government counterparts. The works of Liu and Zhang thus warrant close examination.

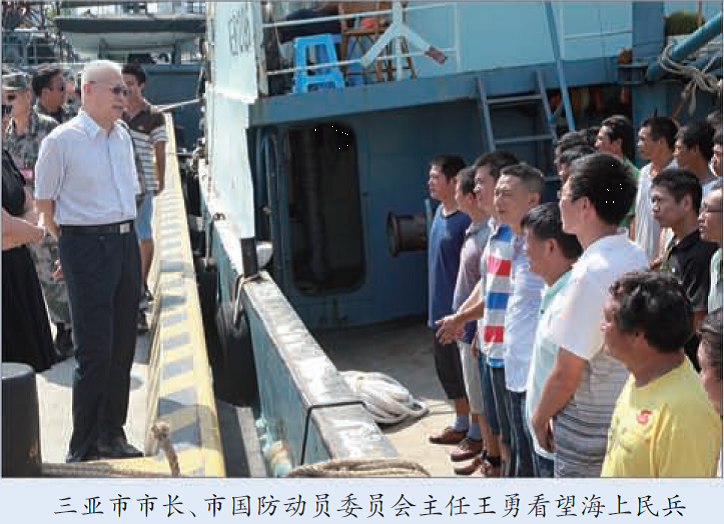

Invoking Chairman Xi’s and the Central Party’s guidance on maritime militia building and “strategically managing the ocean,” Political Commissar Liu Xin focuses on the role of the maritime militia in “maritime rights protection” (efforts to uphold and enforce China’s maritime claims). Liu explains how drawing in the people, especially fishermen, will help give China freedom of action—and the initiative—in maritime rights protection. According to Liu, the bulk of the maritime militia force will comprise the province’s original units, but will be led by newly created emergency response units with “new types” of maritime militia as the core. Evaluations will be strengthened to ensure there is a core force of “new-type fishing vessels” and “elite standing maritime militia emergency response units.” They must “be able to respond when called upon and win emergency maritime rights protection wars of initiative” (打赢海上应急维权主动仗). Liu’s remarks reflect a combination of higher combat readiness levels for emergency response units—i.e., the elite units—and the more regular rights protection roles of the majority of maritime militia units.

News reports state that Liu lead a new initiative in early 2016 to promulgate policies and plans for maritime militia organization and involvement in rights protection. Under his lead, the province passed the “13th Five Year Plan on Hainan Province’s Maritime Militia Construction,” providing systematic planning for missions; as well as guidelines, requirements, and measures for maritime militia building. Liu reportedly devoted great time and effort to key maritime militia construction issues, visiting numerous islands and reefs in the process. He was also reported to have been personally involved in multiple joint training events with active duty forces, emergency response plan drafting, and the strengthening of over ten maritime militia emergency response detachments. He also spent time working with local governments, ensuring that such pressing issues as expenditures and maritime militia base construction were included in their military affairs meetings.

Writing in more operational terms, MD Commander Zhang Jian explains how to increase the professionalization of maritime militia personnel and vessels. According to Commander Zhang, ships must be large-tonnage, high-speed, seaworthy steel-hulled fishing vessels strong enough to withstand collisions. These vessels should be drawn from fishing enterprises and cooperatives whose vessels frequent the sea areas in which their services are required for missions, as well as those vessels whose crews have previous experience engaging in rights protection. Furthermore, material and equipment are allocated according to the requirements of maritime rights protection and naval combat support, including communications and reconnaissance equipment and “defensive combat weaponry.” Personnel from different specialties should be grouped in units according to the following formulation: “Recruit experienced fishermen to serve as vessel operators as well as military personnel and veterans with maritime specialties to be core combatants; and select People’s Armed Forces cadres with maritime rights protection experience and medical staff with at-sea experience to be command and support personnel [respectively].” This implies that a mixture of personnel may crew maritime militia vessels, as embodied in the widespread phrase “determine troops based on the vessel” (以船定兵) for maritime militia organization. This style of organization could also conceivably be tailored to different missions. This is echoed in other provinces as well, such as Liu Xuan, head of the Shuidong Township PAFD in Guangdong Province. He stated in early 2016, “next year we will take in even more experienced and hardened fishermen with good work ethics, bolster them with primary militiamen, and hold targeted training in the subjects of maritime rights protection and war time support.” Liu Xuan’s statement indicates that formerly land-based coastal militia may also be assigned to maritime militia vessels. This demonstrates how local military commands are mobilizing current resources in varying ways to produce stronger maritime militia forces.

Commander Zhang stipulates three types of operations for the maritime militia:

- Their use as “civilians against civilians for regular demonstration of rights” (以民对民常态示权). The government will take the lead in implementing command and organizing maritime militia to fish in even the more remote waters (within the Near Seas) with greater organization and scale. This ensures that a certain number of China’s fishing vessels are present in “China’s waters” at any given time, achieving regular presence and declaration of sovereignty. Maritime militia are to be summoned immediately when foreign civilian vessels from neighboring countries are found encroaching on fishing rights or disrupting Chinese development of islands and reefs, resource extraction, or scientific surveys. Such civilian countermeasures against other civilians are envisioned to gain the initiative rapidly.

- Their use in “special cases of rights protection by using civilians in cooperation with law enforcement” (以民协警察专项维权). Maritime militia will “receive orders” from their command to conduct special rights protection missions when neighboring countries violate China’s maritime rights and interests and when China’s maritime law enforcement (MLE) requires their assistance. This often entails the combining of maritime militia and MLE forces to form a joint law enforcement force, whereby the militia participate directly in rights protection law enforcement actions by supplementing MLE forces. In these actions, together with MLE forces, maritime militia primarily conduct perimeter patrol (外围巡逻), sea area control (海区封控), alerting and expulsion (警戒驱离), confrontation (海上对峙), and combining to push back (合力逼退) foreign vessels.

- “Participation in combat and support-the-front by using civilians to support the military” (以民援军参战支前). When a maritime armed conflict or maritime local war erupts, coastal cities and counties will organize their maritime militia to participate in combat and support-the-front operations, exploiting numerical advantages in personnel and vessels, as well as their familiarity with the seas, islands, and reefs. Units will conduct transport, supply, rescue, repair, and medical support in the Near Seas (Yellow, East China, and South China Seas) and on front-line islands, reefs, and mission areas. Meanwhile, maritime militia will assume direct combat support by coordinating with maritime combat forces to conduct reconnaissance, sentry duty, and guarding against surprise attacks.

The Hainan MD leadership emphasizes that Hainan’s maritime militia forces contain a core set of more professional units with higher levels of readiness, ensuring that militia forces can mobilize rapidly out to sea. These points echo the call to action by Major General Wang Wenqing, head of CMC-NDMD’s Militia and Reserves Bureau, for resolving issues involving maritime militia construction nationwide. He affirmed the emphasis on an elite standing force of maritime militia composed of captains, engineers, and veterans operating year-round. These are the elite front line units that are most likely entrusted with sensitive missions involving foreign vessels, such as potential interference in future U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) and routine operations; as well as the disruption and attempted sabotage of foreign survey vessels.

Joint Military-Law Enforcement-Civilian Defense (军警民联防)

The National Border and Coastal Defense Conference, last held in Beijing on 27 June 2014, provides guidance for the Border and Coastal Defense Committees (BCDC) established to coordinate defense of territorial sovereignty, protect maritime rights and interests, and ensure border security. Organized in a similar fashion as the mobilization work of China’s National Defense Mobilization Committee System, the BCDC system assembles leaders and staff at each level of government and military command into a single body for planning border and coastal defense work. President Xi Jinping stated in the 2014 meeting that China’s border and coastal defense will “wield the features and advantages of joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense” (发挥军警民联防的特色和优势). Also contained in China’s defense white papers, such as the 2013 Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces, and featured frequently in Chinese reporting on the militia, this operational concept has been a part of China’s coastal defense system since the PRC’s founding. It is the primary means for the militia to participate in combat readiness for coastal defense. It entails the mobilization and integration of the various military, law enforcement, militia, and societal forces into a joint defense force.

Today, Hainan Province is actively implementing this joint defense concept. The joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense concept is also often referred to as the “three lines,” with the maritime militia constituting the front line, backed up by a second line of CCG and a third line of PLAN forces. The Hainan MD has reportedly held workshops and major exercises with active duty forces since 2013 to determine campaign and tactical guidance for the maritime militia. Located in a key maritime frontier province, the Hainan MD is continually working alongside the PLAN and CCG to fine-tune its joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense through large-scale exercises.

Provincial Implementation

Following the 2011 National Militia Work Conference, Hainan began a pilot project for maritime militia development in February 2012. The Hainan MD sent research groups to study grassroots maritime militia organizations, gaining better understanding of the force through meetings with unit leaders. On 20 September 2012, the Hainan Province Party Chief and Hainan MD First Party Secretary Luo Baoming launched a Provincial Committee Military Affairs Meeting on the subject of “Advancing to a New Level Party Control of the Military and Construction of National Defense Reserves in Preparation for Military Struggle in the South China Sea.” As Hainan Party Secretary since August 2011, Luo has been a champion of maritime militia building, instructing during a 2015 Provincial MD Conference on Maritime Defense Work that the province “expend great effort to strengthen maritime defense construction focusing on maritime militia.” While Luo was in Beijing in March 2016 working on his province’s 13th Five Year Plan, a Reuters reporter raised the topic of Hainanese fishermen acting as militia. Denying nothing, Luo stated publicly that the fishermen in his province participate in the protection of maritime rights and interests, and undergo training in self-defense. Meanwhile, other influential voices in the province, such as former head of the Provincial Government Center for Social and Economic Development Research Liao Xun, were emphasizing the role of the maritime militia in their writings.

Provincial civilian and military leaders were busy crafting policies and plans for bolstering the maritime militia, releasing the “Opinions on Strengthening Maritime Militia Construction” in 2013. This also resulted in an official “Notice on Further Strengthening Maritime Militia Construction” released by the Hainan Provincial National Defense Mobilization Committee. These two official documents stipulated manifold requirements for the 2013 annual reorganization of the militia force guided by the MD and executed by counties. This annual reorganization process is conducted to implement reforms and correct outstanding issues in militia organizations. The documents also required that provincial and county governments split the cost of maritime militia construction. By the end of 2013, the province added 28 maritime militia companies with 2,328 personnel and 186 vessels to its maritime militia force.

In early 2014, the State National Defense Mobilization Committee, the State Council-level coordinating body, hosted a symposium in Hainan entitled “Maritime Mobilization 1312” to ensure that each level of Hainan’s government focused on maritime militia development. The meeting featured maritime rights protection demonstration events in Tanmen Township’s harbor and also established a leading small group to coordinate the province’s maritime militia construction, headed by Provincial Deputy Party Secretary Li Xiansheng. National directives likely bolstered maritime militia readiness in the province, preparing them for the province-wide mobilization of maritime militia to defend the HYSY-981 oil rig in May 2014.

According to Political Commissar Liu, Hainan will develop its maritime militia in three phases. The first phase entails finding the proper regulations through pilot projects, research and discussion of tactics, and at-sea testing. The second phase will focus on increasing capabilities through intensified training of the new, elite maritime militia and improving its support system. There should also be further testing and evaluation to ensure that the maritime militia are readily available and operationally effective. The third phase will focus on the “regular use” of the maritime militia (mechanisms for enduring maritime militia organization and employment). This effort will integrate units into the “three lines” joint rights protection system and increase their ability to regularly conduct reconnaissance and escort support missions in relatively “remote waters” (within the Near Seas). Progress to date in Hainan’s maritime militia forces suggests that they may have begun phase one after the 2011 National Militia Work Conference; and entered phase two with the development of a core force of maritime militia, through the introduction of increasingly capable vessels, communications equipment, and joint training. Looking forward, increased maritime militia presence in the Spratlys may also be an indicator of advancing progress in phase three.

Since militia building must proceed in accordance with local conditions, different provinces may exhibit distinct practices in organizing their maritime militia forces. Reflecting their large marine economies, Hainan and Guangdong provinces have signed cooperation agreements involving many fields of social and economic development. During the recent meetings to deepen cross-provincial cooperation in September 2015, Hainan Party Secretary Luo made several proposals for the two provinces. These included cooperation in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, marine science and technical research, maritime joint rescue, rights protection and law enforcement, and—most pertinent to this article—maritime militia construction. It remains unclear if the provinces have fostered some form of cooperation regarding their respective maritime militia forces. In October 2015, however, Sansha City mayor Xiao Jie hosted a forum to consult with Guangdong- and Guangxi-based fishing companies on the development of Sansha’s marine fishing industry, including the Sansha Fisheries Development Company, a state-owned maritime militia organization. Cooperation in maritime rights protection efforts was one of Xiao’s key points to Guangdong and Guangxi fishing companies, suggesting that Party Secretary Luo’s provincial maritime militia cooperation initiative may have gained traction rapidly.

Despite apparent enthusiasm within Hainan’s leadership, however, there appear to be broader concerns about the lack of initiative shown by local governments across China in building the militia, centering on the “separation between construction and use” (建用分离). With little prospect for utilizing reserve forces, local governments may show less enthusiasm for supporting their construction. For example, the Lingshui County Government leadership used to avoid meeting its military counterparts, which previously consumed money and materials without providing reliable troops to respond in emergencies. Having the militia serve as a source of manpower during emergencies and disasters helps rectify this discrepancy, as encapsulated in the oft-used slogan “a reserve force that responds in times of war and emergencies” (一支战时应战、平时应急的后备力量).

The Tanmen Maritime Militia, for instance, is lauded for its daring rescues of mariners in distress over the years, providing an organic emergency response force that is most familiar with local marine conditions. A recent example was when the Sansha Maritime Militia was mobilized when a Hainanese fishing vessel ran aground near Fiery Cross Reef on 28 February 2017. Having received numerous distress calls, the Sansha Maritime Militia mobilized one of its vessels, Qiongsanshayu 000312, to attempt a rescue. However, shallow waters and poor weather conditions prevented them from getting close enough. After two days of standing by, a nearby PLAN helicopter flew in to evacuate the stranded fishermen.

Maritime militia play a significant role in responding to emergencies, helping local governments with search and rescue and disaster relief. When PLAN aviator Wang Wei went down in waters 70 miles south of Hainan after colliding with a U.S. Navy EP-3 plane in 2001, Hainan’s fishing fleet and militia contributed notably to the search effort. Sanya City alone organized over 500 fishing vessels to search at sea while more than 4,000 people and militia scoured the coast for Wang. Sanya’s PAFD Head Zhou Naiwu also ordered the Tianya Maritime Militia Rapid Response Unit out to sea to join the effort. Other neighboring localities involved included Ledong Autonomous County, which dispatched hundreds of fishing vessels and over 3,000 cadres, militia, and fishermen. That event demonstrates direct support by local government-built militia forces for national military objectives. Today, increasingly capable maritime militia forces can more effectively assist local governments and military organs in responding to future emergencies at sea.

Conclusion: Trolling Together for Sovereignty Claims

A confluence of national strategy, structural reforms, and development plans has informed China’s future national militia development, giving increased prominence to the maritime militia. The front-line maritime militia units documented throughout this series have developed and operated within the Hainan MD’s evolving reserve force structure and PLA chain of command. As such, Hainan’s principal military and civilian leaders have critically shaped maritime militia force development, and continue to do so. Part 1 of this series has illustrated how national-level guidance has resulted in actual implementation in China’s key maritime frontier province, and how the Hainan MD leadership envisions the construction and use of maritime militia under its jurisdiction in the South China Sea. Additionally, while fishermen constitute a core body of personnel to operate maritime militia vessels, there may also be a variety of other personnel aboard to fulfill other functions within their units. Part 2 will address specific policy implementation to date, and how Hainanese officials are working to manage challenges in maritime militia development to achieve further progress. Part 3 will evaluate the results of Hainan Province’s maritime militia construction and suggest corresponding implications. Due to the varying economic conditions and geographies among the provinces, understanding how MD leaders execute maritime militia force planning, construction, training, and utilization can help to anticipate the extent and limits of Chinese Maritime Militia capabilities at sea.

Conor Kennedy is a research associate in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He received his MA at the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board. He is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and an expert contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time Report. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com. The views expressed here are Erickson’s alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

Featured Image: June 2013 Sansha Maritime Militia personnel were sent to a militia training base on Hainan Island to receive a week of intensive training by the Hainan Provincial Military District, including weapons training as shown in this photo.