The report At What Cost a Carrier? published by CNAS and written by CAPT Henry J. Hendrix contains all the necessary ingredients for a simple model-structuring discussion about the validity and viability of the “Carrier Force” concept. With such a model, individual variables can be discussed or discarded without undermining the need to answer the leading cost question or the model itself. These are the basic variables we get with a carrier:

- Influence: The amount of influence a navy can project on the world is indirectly measured by carrier military power – sets of “90,000 tons of diplomacy” – and not limited to it. In fact, the rest most of the world uses other means to influence events in order to achieve favorable outcomes. Other nations may want a carrier but, because they cannot afford one, have to look for alternatives.

- Cost: The cost of achieving a carrier’s desired capabilities, whether measured by the price of procurement, life-cycle cost, or the cost to restore damaged capabilities during armed conflict. Inversely, not building carriers incurs the cost of losing industrial base and know-how.

- Risk: This is commonly understood as vulnerability from a lack of assets (the risk of going without), but there are also consequences of losing a carrier. The magnitude of lost military power, cost, influence, and image in such a case would enormous.

Military effectiveness-related attributes, like striking power and affordability, are relatively easy to measure and remain at the center of discussions. On the other hand, political-value calculations are less structured (and harder to quantify) but probably represent the biggest threat to the carrier-centric concept, especially if linked with a shift in strategy. What is the acceptable Cost to have X amount of Influence? Or to reduce X amount of Risk? Is increasing Influence worth increasing Risk? What is our strategy to have Influence on opponent?

There are many examples of proposals aimed at undermining the delicate balance between the above attributes.

During the 1980s, Surface Action Groups (SAGs) built around battleships (then still in service) were considered partial substitutes for Carrier Battle Groups (CBGs). It was a compromise, which in effect supplemented carriers but did not replace them.

In the same category we can place contemporary “Influence Squadrons.”

“If the Navy rethinks the role of Carrier Strike Groups (Ferrari) and deploys new, scaled-down Influence Squadrons (Ford), the result will be 320 hulls in water for three-quarters the price,” said Capt. Hendrix. This fits well with the trends of other nations, purchasing LPH-class helicopter carriers as affordable naval air power, and spurs grim predictions for carriers from bloggers:

Were Humphrey a betting man, then he’d be willing to place a small wager that within 20 years, there will be six nations operating aircraft carriers (down from nine today), and only two of them will be in the West…

Sir Humphrey depicts the world (almost) without carriers and shows how easily – through the cascading effects of delayed deployments, reduced training, and backlogs in nuclear refueling – sequestration could drastically reduce U.S. naval air power (or its useful part). In this context, if the variables above are the right ones, than DF-21 is the modern equivalent of the Star Wars project and cruise missiles from Cold War-era. Development of these weapon systems created such strong financial pressures on their opponent that they ultimately put the enemy’s whole system on the edge of collapse. DF-21 is presented as a weapon targeting carriers’ vulnerabilities, but in a way it becomes strategic weapon with political calculations behind it.

Ballistic missiles represent yet another area of exploration, which potentially could result in changing the prime positions of carriers in a national defense portfolio. We’ve lately seen the latest attempts to reinvent conventionally armed Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs). These concepts are not new and in this case risk-calculation will probably prevail, as launching ballistic missiles from submerged submarines creates a danger of triggering nuclear conflict as the adversary may have a hard time differentiating the conventional launch from the nuclear variety.

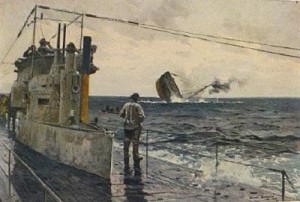

The impression is that there is no threat today to aircraft carriers’ primacy because they still represent such a large capability to influence events. Experimenting with other alternatives shouldn’t be viewed as a budgetary threat to carriers but rather as a way to limit the risk if an opponent changes the balance between Influence, Cost, and Risk in favor of other means or weapon systems. The time elapsed between construction of HMS Dreadnought and the Jutland Battle was only 10 years. In the battle, the British Grand Fleet validated the concept of the distant blockade of Germany, but at the same time forced Hochseeflotte to switch resources toward U-Boats, which in turn made the Grand Fleet obsolete in maintaining a distant blockade. Preparing defensive measures against the new threat was costly during the war and forgotten in peacetime.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is broad context of purpose and structure of Navy and promoting discussions on these subjects In his country