Zephyr

In the din of East African security issues, the navy of Africa’s most populous nation has fallen out of the international eye. With continued pressure on diversified procurement, increasing capability, and new international cooperation, Nigeria’s Navy is slowly growing to fill a void dominated by piracy, petroleum smuggling, and other criminal elements that is re-engaging international attention in Western Africa. Whereas the state of Somalia has been quite unable to manage its offshore affairs, the Nigerian Navy has plotted a course out to sea under the pall of its severe security challenges. If the challenges of oversight, funding, and collusion don’t capsize their efforts, it may become a quite fine sailing.

Procurement-Let’s Go Shopping:

Since 2009, Nigeria has been pursuing an aggressive new procurement program. During the last Nigerian naval modernization period, the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, Nigeria purchased a vast number of vessels from Germany (LST’s) , France (Combattantes), the UK (Thornycraft), Italy (Lerici minesweepers), and others. Unlike the procurement processes familiar in larger navies, such those of NATO, Nigeria ran an “open-source” program, pulling already-proven foreign systems off the foreign shelf. This new buildup is similar, with some new attempt to build local ship-building capacity.

The three big ticket “ship of the line” purchases are the 2 “Offshore Patrol Vessels” and the NNS Thunder. The NNS Thunder is the old school “off the shelf” style ship purchase, bringing a Hamilton-class High Endurance Cutter, the ex-USCG Chase, into Nigerian service in 2011. The “Offshore Patrol Vessels” were commissioned with China Industry Shipbuilding Corporation and approved for purchase by President Jonathan in April of 2012. The fleet’s major combatant until the NNS Thunder was the NNS Aradu, an over 30 year old vessel and Nigeria’s only aviation-capable ship. The new contenders will add a total of 5 new 76mm Oto Melara’s added to the fleet, a none too shabby improvement of overall firepower for littoral operations. The 45 (NNS Thunder)/ 20 (OPV’s) day endurance will give the Nigerian Navy an impressive new stay-time for continuous at-sea opeartions. Arguably most important is that all three vessels have maritime aviation capabilities that will greatly expand the reach and ISR component of Nigerian maritime operations. These three ships are right on target to fill critical gaps in Nigeria’s capabilities.

Nigeria’s littoral squadrons are also scheduled for improvement. Nigeria is purchasing several brown-green water patrol craft to bolster her much-beleaguered inshore security where smuggling of all kinds is rife. Singaporean Manta’s and Sea Eagle’s, US Defender’s, Israeli Shaldag Mk III’s, and others will add potent brown and green water assets to Nigeria’s toolbox.

However, not all of Nigeria’s purchases are imports. Thi package also begins the cultivation of indigenous ship-building capability. One of the aforementioned OPV’s is scheduled for 70% of its construction to occur in Nigeria. To more fanfare, the NNS Andoni was commissioned in 2012. Designed by Nigerian engineers and produced locally with 60% locally sourced parts, it is considered a good step forward for building local expertise and capability in the realm of the shipwrights. More local capacity and expertise will further increase the ease with which ships bought locally, or abroad, can be maintained.

-But Avoid the Bait and Switch!

While flexible, this off-the-shelf model can lead to some bad dealings either by vendors or government buyers. Flexible US defense procurement specialists would love more unilateral authority and oversight compared to their gilded cage of powerpoint nightmares. However, the opposite can lead to incredibly terrible purchasing decisions. While Nigeria’s 2 OPV’s are running for current a total cost of $42m, a proposal was made to purchase one 7 year old vessel for $65m dollars. That vessel had a further $25m in damage that needed to be repaired. That particular vessel now sails as the KNS Jasiri after a large financing scandal of several years ended. At the time of delivery it appeared completely unarmed as well, though since it has since had weapons installed. If one were to ask why Nigeria would want to buy a single unarmed vessel with no aviation capability for the price of 4 more gunned-up and helo-ready OPV’s, the answer is probably not a “clean” one. Oversight is going to continue to be an issue in a country with one of the bottom corruption ratings.

Capability- Shooting more, shooting together :

Ships are all well and good, but what matters is what you do with them and how. Though the scale of offshore criminality is likely in total hovering around 10 billion, and the entire naval budget is roughly a half billion, the Nigerian Navy is moving more aggressively to course-correct their coastal regions. Several instances include a successful gun battle in August, ending the careers of six pirates, further arrests for oil theft in september, and a nice little capture of pirates in August for which photo opportunities were ensured for the press. The Nigerian Navy is further attempting to extend the “immediacy” of their reach by establishing Forward Operating Bases, like the ones at Bayelsa and Delta states. These and many other instances are the nickles-and-dimes as the Nigerian Navy chips away at the corners of their behemoth security challenge at sea. Every journey begins with a single step, and though the Nigerian Navy has reached a bit of a trot, they have a long way to go. But even in the Navy, no man is an island. With a limited budget and math-rough half of the budget going to the army, the Nigerian Navy needs support. The civil and military authorities are moving closer to that “joint” model with the Memorandum of Understanding between the Nigerian Air Force (NAF) and the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) on the use of NAF assets in Anti-Piracy operations. With an existing MoU between NIMASA, this creates further points of coordination between civil, naval, and air force assets in a coordinated battle against criminals at sea. It’s no J3/J5 shop, but it’s a start.

-But Don’t Undershoot!

The Nigerian Navy’s take from the $5.947bn defense budget is a cool $445m. This is a continued increase for both the defense budget overall and the navy budget specifically and is expected to continue increasing. While this is all well and good, the Nigerian Navy faces a criminal enterprise worth billions: Piracy ($2bn), Oil Theft: ($8bn), and others. The Nigerian Navy itself has a way to go with shoring up its vast body of small arms, ammunition, and gear. In 2012, a fact-finding mission by members of the Nigerian senate found an appalling state of affairs in regards to equipment shortages, maintenance, and a whole slew of other steady-state problems. Enthusiasm and new ships can only go so far. The Nigerian Navy needs to spend the extra money to shore up their flanks, refurbishing or replacing their vast stock of older ships, weapons, equipment, and ordnance stores (without forgetting training).

Cooperation- Team Player:

Nigeria is no stranger to international cooperation. Many forget that in August 26th, 1996, ECOMOG (under ECOWAS) actually conducted an amphibious assault into Liberia led by Nigerian military units. From peacekeeping in Liberia, to Sierra Leone, to Darfur, to Mali, etc… etc… Nigeria troops have been a staple of many peacekeeping efforts. Now, their typical face abroad, the boots on the ground, is pulling back to the homeland to fight Boko Haram. However, the navy is still extending its project to integrate into partnership programs through both engagement at home and extending the hand abroad. Nigeria is an active catalyst of the regional security regime. For one, ECOWAS is a factor at sea as well as land. At an ECOWAS conference ending 9 OCT, the naval chiefs of Nigeria, Niger, Benin, and Togo agreed to a common “modality” for the combating of terrorism and agreed to set up a “Maritime Multinational Coordination Center” in Benin to coordinate security efforts. It also doesn’t hurt to host the maiden run of a major procurement/policy forum in your continent, namely the “Offshore Patrol Vessels Conference” for hundreds of African and interested parties. Networking, though an intangible product, is an important way of building institutional strength and connections. Nigeria also engages with US and NATO training missions, like the most recent Operation African Wind: a training exercise for the Armed Forces of Nigeria and other regional militaries in conjunction with the Netherlands Maritime Forces under the auspices of the United States sponsored African Partnership Station. In Lagos and Calabar, units will learn about sea-borne operations, jungle combat, amphibious raids, etc… over 14 days of training and 4 days of exercises. Finally, Nigeria’s navy has made a very respectable show of striking out by conducting a “world tour” of sorts with the new NNS Thunder. The NNS Thunder made a tour around Africa before crossing the Indian Ocean for an historic visit to Australia this month for International Fleet Week. The Nigerian Navy seems determined not to remain shackled by their previous bad position, and is aggressively pursuing an expanded mission and self-image through more than just procurement. Despite the challenges ahead, they’ve demonstrated a reach few of their continental compatriots can lay claim to. It may not help against pirates, but it should be a fine addition to espirit de corps.

-But Also Collusion, Not Always the Right Team…

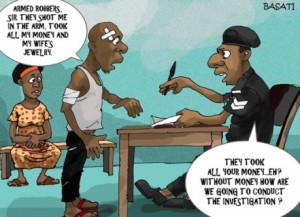

However, while the navy coordinates with foreign navies, some officials in Nigeria coordinate with the criminal elements. Such “industrial scale” theft of oil in particular would be impossible without the involvement of at least some security officials and politicians. The wide-spread collusion helps stall policies designed to curb the vast hemorrhaging of wealth, since the wealth is hemorrhaging to some with influence on the levers of power. This collusion is further muddled by the revelations about government payments to stop oil theft. While a pay-off policy might be effective in the short term, as it has been in Honduras, the long-term promise is muddled, especially if it turns off the money spigot to those receiving graft. While corruption has improved since the end of the patronage-heavy military state, some see very little hope at all: from the luxurious government salaries to wholesale theft from government coffers. Whatever the case, even local perceptions of transparency are depressingly negative. If internal collusion with the criminal underground cannot be controlled, the Nigerian navy will never find itself with truly enough allies to defeat the foe some of their leaders look to for wallet-padding.

Right Course, Add More Steam:

The Nigerian Navy is making good progress. With new ships, expanded operations, and continued engagement the bow is pointed in the right direction. However, without maintaining the engineroom and navigational equipment by battling corruption and putting enough fuel in the diesels by increasing their defense budget, the Nigerian Navy will find itself floundering in the storm.

Matthew Hipple is a surface warfare officer and graduate of Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. He is Director of the NEXTWAR blog and hosts of the Sea Control podcast. His opinions may not reflect those of the United States Navy, Department of Defense, or US Government. Did he mention he was host of the Sea Control podcast? You should start listening to that.

Somaliland and Puntland’s hostility towards a Mogadishu-based coastguard in part stems from the fact that they have already, with external assistance, established their own marine police forces. In 2006, the self-declared state of Somaliland engaged the services of Norwegian PSC Nordic Crisis Management (NCM) to increase safety, security and revenue at the port of Berbera by implementing International Ship and Port Facility Security Code standards. The firm’s contract also involved training Somaliland’s harbor security and marine police forces and consulting on coastguard procurement. The fact that organized piracy did not take root in Somaliland and that NCM was able to complete their five-year contract without serious interruption attests to the success of the project.

Somaliland and Puntland’s hostility towards a Mogadishu-based coastguard in part stems from the fact that they have already, with external assistance, established their own marine police forces. In 2006, the self-declared state of Somaliland engaged the services of Norwegian PSC Nordic Crisis Management (NCM) to increase safety, security and revenue at the port of Berbera by implementing International Ship and Port Facility Security Code standards. The firm’s contract also involved training Somaliland’s harbor security and marine police forces and consulting on coastguard procurement. The fact that organized piracy did not take root in Somaliland and that NCM was able to complete their five-year contract without serious interruption attests to the success of the project.