By Ben DiDonato

Introduction

As the U.S. Navy moves into the unmanned age and implements Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO), there is a need for small, lightly manned warships to streamline that transition and fill roles which require a human crew. Congress has expressed concerns about unmanned vessels on a number of fronts and highlighted the need for a class of ships to bridge the gap. The Naval Postgraduate School’s Lightly Manned Autonomous Combat Capability program (LMACC) has designed a warship to meet this need.

The need for these small, heavily armed warships has also been well established, and is based on extensive analysis and wargaming across the Navy’s innovation centers. These ships will provide distributed forward forces capable of conducting surface warfare and striking missile sites from within the weapons engagement zone of a hostile A2/AD system. They will be commanded by human tactical experts and operate in packs with supporting unmanned vessels, like the Sea Hunter MDUSV, to distribute capabilities and minimize the impact of combat losses.

Our intent with this article is to publicly lay out the engineering dimension of the LMACC program. Since the United States does not have a small warship to use as a baseline, it is necessary to first establish what our requirements should be based on our unique needs. Fortunately, this can be accomplished in a relatively straightforward manner by broadly analyzing how foreign ships are designed to meet their nation’s needs, and using that understanding to establish our own requirements. As such, we will start by examining the choices faced by other nations, use that to develop a core of minimum requirements for an American warship, examine its shortcomings when compared with other budget options, and finally discuss how to affordably expand on that to deliver a capability set the Navy will be happy with. Once we have established our requirements and overall configuration, we will conclude with a discussion of our approach to automation, manning, concepts of operations, future special mission variants, and current status.

(The scope of this article has been deliberately limited to the engineering side of the LMACC program. Our acquisition approach will be discussed in an upcoming issue of the Naval Engineers Journal. Fleet and budget integration was discussed in a previous article on USNI blog, “Beyond High-Low: The Lethal and Affordable Three-Tier Fleet.”)

Examination of Foreign Designs

Due to our relative lack of practical domestic experience in the field of small warship development, we will start with an examination of foreign designs to build a transferable understanding of their capabilities, limitations, and design tradeoffs. Since there are many ship classes used worldwide, it is impractical to discuss every example individually. We will instead discuss mission areas and compromises in generic terms and leave it to the reader to consider how specific foreign designs were built to meet their nation’s needs. Areas of design interest include anti-ship missiles, survivability, anti-submarine warfare (ASW), and launch facilities. The first three subsections divide the discussion between large and small nations, while the final subsection is split by type of launch facility. Each subsection then concludes with a discussion of how this translates to the United States’ unique situation. This will then set us up for the subsequent discussion of the basic preliminary requirements for a generic small American warship.

Anti-Ship Missiles

Small warships are frequently given labels like “missile boat” or “corvette” based on their primary armament of anti-ship missiles with little further thought. However, not all missiles are created equal. The choice of missile is driven by the platform’s intended use.

Small nations (e.g. Norway) attempting to defend themselves on a limited budget typically prioritize lethality with a highly capable missile designed for sinking major warships. However, because they often face limitations in offboard sensors, strategic depth, and force structure to absorb combat losses, they tend to sacrifice range and networking capability to control missile cost and weight.

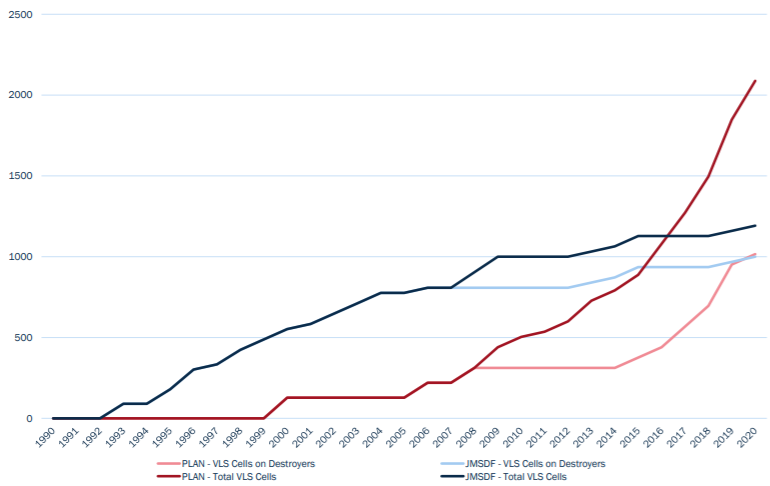

Large nations prioritizing coastal defense against a more powerful opponent (e.g. Russia and China’s A2/AD systems) tend to view their small warships as part of a larger system. These ships are intended as much to complicate enemy targeting and defensive formations as they are to sink ships. As a consequence of this, they are more likely to invest in range and networking since they can reasonably expect to take advantage of it, but may be willing to save money by arming these ships with less expensive, and therefore typically less lethal, weapons.

Due to the nature of the U.S. Navy’s highly networked, forward deployed forces, we cannot accept these compromises and must arm our small warships with highly lethal, long-range, networked weapons.

Survivability

A major concern with all warships is survivability. One of the key distinguishing features of small warships is how they address this problem. Rather than rely on a large, expensive missile system to destroy threats at long range, these small warships instead rely primarily on avoiding attack and feature only limited point defense weapons. This is achieved through a combination of small size, signature reduction, electronic warfare, and tactics.

It is important to remember other nations are frequently focused primarily on pre-launch survivability rather than a counterattack based on the missiles’ signature. This lack of focus on post-launch survivability is generally based on the assumption that the cost ratio of the exchange will generally be in their favor even if they lose the ship. Another important consideration, especially for smaller nations, is that their ports are usually very vulnerable to a standoff strike, so surviving ships may not be able to rearm or refuel and are therefore effectively out of action even if they do survive. For large nations with sophisticated A2/AD systems, protecting these ships is usually primarily the responsibility of other platforms, allowing significant savings by reducing survivability-related costs.

Smaller nations usually invest more in survivability features and trade endurance for extremely high speed to improve their odds of getting into attack position before they are sunk. They also commonly employ tactics to make their ships difficult to track in peacetime by exploiting maritime geography and blending into commercial traffic to avoid a preemptive strike.

The United States can count on having a safe port to rearm somewhere, even if it requires withdrawing all the way to CONUS, so we would need to further emphasize evasion since these ships would have to persist within hostile A2/AD networks even after launching missiles. This means it would be essential for a small American warship to use a stealthy, networked missile capable of flying deceptive routes to mask the launch point, as well as the best electronic warfare equipment, passive sensors, and acoustic signature reduction we can afford. Other forms of signature reduction are an interesting question because there is a risk of standing out from civilian traffic if the warship’s signature is significantly different from those around it. After all, a Chinese maritime patrol aircraft could easily recognize that a “buoy” making an open-ocean transit is actually a small warship. On the flipside, we have no need for the high speed favored by many foreign nations, especially since blending in with slow-moving civilian traffic will be a critical aspect of survivability. Therefore, we should trade speed for range to control cost and project power from our generally safe but distant ports.

One final U.S.-specific feature which could greatly enhance survivability inside A2/AD networks, reduce range requirements, and reduce the logistical burden is the exclusion of gas turbines in favor of diesel engines. This will allow these ships to stop at any commercial port to take on diesel fuel, and possibly food, while further enhancing the illusion that they are small commercial vessels. With some imaginative leadership, this will provide virtually unlimited in-theater range and loiter time with minimal logistical support, simplifying our operations and complicating the situation for the enemy.

ASW

While many small warships include ASW capability, they are usually intended to operate as coastal area denial platforms rather than oceangoing escorts or sub-hunters. For nations worried about hostile submarines, this area denial provides essential protection to ports and other coastal facilities which would otherwise be extremely vulnerable. In contrast, performing the latter high-end missions requires the large aviation facilities and expensive sonars of a frigate or destroyer.

Thanks to our large nuclear-powered attack submarine fleet and the remoteness of hostile submarine forces, we don’t need a small surface ship to defend our ports from submarines, so this ASW equipment is generally best omitted. The U.S. only needs the ship to have a reasonable chance of surviving in a theater with hostile submarines, and this can be most economically provided by acoustic signature reduction and appropriate tactics. In fact, the active sonar systems used for area denial by other nations would be detrimental in American service since they let hostile submarines detect the ship from much further away.

Launch Facilities

Many small warships include launch facilities of some form for boats, helicopters, small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), and underwater vehicles (UUV).

A boat launch facility is very important for a variety of maritime security operations and general utility tasks including allowing access to unimproved coastlines. Thanks to this utility and their modest space and weight impact, they are found on many small warships. It is also important to note that a boat launch facility can generally launch USVs of similar size if desired to perform a variety of functions including acting as offboard sensors and decoys.

While the utility of naval helicopters is well established, they are relatively uncommon on small warships. Adding full aviation facilities requires a major increase in ship size, crew, and cost. Even a simple helipad for vertical replenishment has a major impact on topside configuration. Furthermore, helicopters are relatively visible and can thus make it much easier for an adversary to distinguish the warship from civilian traffic.

A much more common way of providing aerial surveillance for small warships is small UAVs. Because they can easily be added to existing ships, they have become common additions to small military and coast guard vessels worldwide. These aircraft provide many of the benefits of a helicopter with a much lower signature and little to no design impact on the ship. Furthermore, considering their proliferation in the civil sector, launching a small UAV is no longer a recognizably military activity. It is reasonable to assume all future designs will at least consider the operation of hand-launched drones, and it is highly likely many will also integrate launch systems for larger assets as well.

While UUV launch facilities are currently relatively rare outside dedicated MCM platforms, the maturation of this technology makes it worthy of more general consideration. UUVs could perform a range of other missions including undersea search and interacting with undersea cables without the need to specialize the ship itself. Furthermore, the launch facilities could also be used to transport additional MCM UUVs for use by other ships. As such, it seems likely this capability will proliferate since the launch facilities aren’t especially large, although it is still too early to say for certain exactly how useful it will actually be.

For the U.S. Navy, the only truly critical launch capability is small UAVs to enable over-the-horizon surveillance and targeting. Our enduring presence requirement means we will almost certainly want some form of boat launch capability to support those missions. We may want UUV launch capability as well, but it likely does not meet the bar to be a minimum requirement.

Minimum Requirements for a Small American Warship

Based on the above discussion and a few common practices, the list below provides a reasonable set of approximate minimum requirements for any small American warship. Note that this is not our final design, but a simplified interpretation using current technology and standard design practices:

- Eight LRASMs

- SeaRAM

- Latest generation full-sized AN/SLQ-32 electronic warfare suite

- Standard decoy launchers

- Excellent optical sensor suite:

- Visible Distributed Aperture System (DAS)

- IR DAS

- Visible/IR camera turret

- Maximum affordable acoustic signature reduction

- Appropriate reduction of other signatures to blend into civilian traffic

- COTS navigation radar

- Low probability of detection/intercept datalinks

- 30-knot speed (approx.)

- 7500+ nautical mile range

- One 7m RHIB

- Small UAV storage and launch accommodations

- Traditional light gun armament

- One 30mm autocannon

- Two M2 Browning heavy machine guns

It has been assumed that the likely boat launch facility is included while the more tentative UUV launch facility has been omitted. The range was selected to allow the ship to sortie from one island chain to the next and back (e.g. Guam to the Philippines) on internal fuel, and it also makes it relatively easy to operate over even longer distances using extra fuel bladders and/or limited refueling. Speed is not exact since small changes wouldn’t have a major impact, and no attempt was made to identify a displacement or crew complement because it is not immediately relevant to this example.

While the above requirements are obviously distinct from any current design, they should be immediately recognizable as the rough outline for a fairly conventional small warship tailored to the needs of the United States Navy. More work would obviously need to be done to refine this into a finalized set of requirements, but it is close enough to analyze how this conventional design compares to other hypothetical budget priorities and show why we did not simply settle for this minimum configuration.

‘Adequate’ is Not Enough

In any discussion of hypothetical designs, it is critical to keep key alternatives and counterarguments in mind. In the case of small warships, the most relevant argument that might be presented is that aircraft can do the job better. This can take many forms of varying strength, but attacking a weaker form undermines the discussion. Thus, a hypothetical, purpose-built, bomber-like anti-ship aircraft will be considered here. The comparison with the aircraft described in this section will be used to demonstrate the shortcomings of the ‘adequate’ warship described above and set up a discussion of how to make it worthwhile.

This hypothetical aircraft would be a large, stealthy flying wing built using technology from the F-35. Using these electronics eliminates much of the cost of new development and eases maintenance by sharing logistics between this hypothetical anti-ship aircraft and the F-35. In addition, the new low-maintenance stealth coatings will eliminate the headaches of older designs like the B-2, and the design would be further simplified since its mission doesn’t require extreme stealth. It only needs to be able to attack hostile warships before they can detect it, which is not particularly challenging given the range of LRASM and the sensor performance inherited from the F-35. Thus, the cost should be relatively low.

For the sake of argument, it will be assumed this aircraft costs $300 million and carries 24 LRASMs, although better numbers may be possible. This compares cleanly with the small warship which would cost a little under $100 million and carry 8 LRASMs, so the cost per missile carried is approximately the same and we can focus on other performance parameters.

The ship has three key advantages: persistence, presence, and attritability. The first two stem from the obvious fact that a ship can loiter much longer than an aircraft, which makes it better for keeping weapons on-station in wartime or demonstrating American interest by performing a variety of low-end missions in peacetime. The third stems from the fact that we can afford three ships for the price of one aircraft, so an equal investment will provide more ships and losing one costs less, assuming the crew is recovered. While attritability is a benefit in a high-end war, the peacetime flexibility provided by the enhanced persistence and presence is less of a concern in the current geopolitical environment. Finally, this ship may be able to provide some amphibious lift for small USMC units operating under their Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept, although its inability to provide meaningful fire support will limit its utility if an island is contested.

In contrast, the aircraft has numerous wartime advantages. The obvious speed advantage means the aircraft can respond to a developing situation and rearm much faster than ships. This further combines with its altitude to allow a single aircraft to survey a much wider area than the three ships can in spite of their persistence advantage. Furthermore, its combination of long detection range and stealthy airframe means the aircraft is more likely to see hostile warships before they see it, providing a major advantage over ships with respect to survivability and firing effectively first. Finally, thanks to its F-35 architecture, the aircraft will be compatible with a wide range of standard ordinance like the AGM-158 JASSM, AIM-120 AMRAAM, AGM-88 HARM, GBU-39 SDB, and so on, allowing it to perform other missions.

From this comparison, it is clear that those deciding which program to fund will not choose the ‘adequate’ small warship because other programs like the aircraft described above offer a greater return on investment. More capability is clearly needed to make the ship worthwhile.

Going From Viable to Worthwhile

The challenge with solving this problem is that it must be done without compromising the cost and size of these ships. The addition of desirable features led to the size and cost growth of LCS out of the original Streetfighter concept. Subsequent additions to fit into the traditional concept of a frigate with the FFG(X) program have produced a vessel with capabilities, and by extension costs, approaching that of the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer.

To retain the advantages of a small warship and keep it from growing into another Burke, two fundamental options are available: enhanced launch/support facilities, and secondary armament reconfigurations.

This section will explain how the LMACC program addresses this problem and provide the full design details for our baseline configuration. We have made significant enhancements to our launch and support facilities to improve overall utility, and have detailed plans for providing sealift support to the USMC during distributed operations. For the secondary armament, we took advantage of the interactions between technologies to provide much greater lethality against smaller surface threats and to restore the ability to provide robust fire support for Marines ashore at comparable cost.

Launch and Support Facilities

Before diving into how this ship will integrate with the Marines’ EABO concept, we will briefly circle back to the previously discussed launch facilities. UUV launch facilities, while not essential, have been included to provide additional flexibility at low cost, and are designed to benefit from the stern launch ramp required to support EABO. Furthermore, thanks to the small crew and wide beam, we were also able to fit an 11m RHIB to provide additional utility and transport capacity. Helicopter accommodations on the other hand have a major design impact even for a relatively minimal landing pad, especially in terms of manning for maintenance and support, so it has been omitted in favor of a topside UAV locker.

While the Marines are correct to pursue dedicated transports to implement EABO, the surface combatant fleet can also provide limited sealift support. A DDG-51destroyer would have to provide this support on a not-to-interfere basis, but our ship will be an integral part of the mission. The normal wartime employment of these ships will see pairs sortie into the same contested littorals the Marines intend to operate in, so they will supplement the dedicated transport fleet by carrying light units and supplies. LMACC has two empty six-person cabins, plus four extra beds in the crew cabins, so a tactical pair can easily carry a Marine platoon between them with hot racking. These cabins will also provide space for detachments, and one will be equipped to serve as a brig in support of peacetime patrol and partnership missions.

The other half of providing sealift support is delivering the embarked Marines ashore. Features such as shallow draft, pumpjet propulsion, and COTS navigation sonars will allow these ships to get very close to shore to facilitate rapid transfer, possibly even including swimming. Readily accessible stowage spaces at the forward end of the launch bay support rapid transfer of equipment and support use of the inflatable Combat Rubber Raiding Craft (CRRC), while oversized lower-deck cargo bays provide ample storage space. Finally, small boat operations have been greatly enhanced by combining a fully enclosed bay with a stern launch ramp to facilitate rapid Marine deployment, especially in inclement weather or at night.

It should also be noted that the attributes which make it well-suited to supporting the Marines also make it well-suited to supporting Special Forces.

Rethinking the Secondary Armament

For secondary armament, we took the overall configuration back to its fundamental requirements: short-range small boat defense, long-range small boat defense, area land attack, precision land attack, and limited air defense. This allowed us to rethink our approach to those requirements and take advantage of the interactions between modern weapon systems to get better results than a traditional deck gun.

The key technology that enables our layout is the unassuming Javelin Launch Tray. This adds a Javelin missile launcher to a standard pintle mounted weapon, and allows a loader/gunner team to outperform a 30mm autocannon with greater range and comparable engagement rate at greatly reduced weight and installation cost. While this is a useful supplementary defense on existing ships, the large number of installations makes LMACC an excellent escort against small swarming threats and, more importantly, amply satisfies the short-range small boat defense requirement without a deck gun. This may seem less important at first glance since these types of threats are typically associated with Iran, but China has already developed a small USV to perform a similar mission, making this threat relevant to the high-end fight. Javelin also provides a limited anti-aircraft capability since it was designed to destroy helicopters as well as tanks.

Since there is no need for a traditional multi-million dollar deck gun, LMACC instead mounts a 105mm howitzer. The cased ammunition of this weapon makes it suitable for sea service, unlike the larger, separately-loaded 155mm version. As a traditionally towed artillery piece, it is a lightweight, low cost weapon ideally suited to land attack. This of course addresses longstanding concerns about naval gunfire, and is directly relevant to supporting the Marines.

These two weapons fill the short-range small boat defense, area land attack, and limited air defense requirements, leaving long-range small boat defense and precision land attack. These two remaining requirements are both addressed through the addition of Spike NLOS missiles. This allows small surface threats to be safely engaged from over the horizon, and allows armored vehicles and other point targets to be precisely eliminated as well. This complements the howitzer and Javelin to provide excellent anti-boat capabilities and robust fire support for Marines ashore.

The final weapon system is the Miniature Hit-To-Kill (MHTK) missile, which provides additional defense against low-end aerial threats like small UAVs and rockets. This further improves survivability, especially against swarming threats, and ensures the air defense capabilities of a deck gun are fully replicated.

The result of this is a much more flexible and lethal armament with relatively low installation weight and cost. This makes our armament unequivocally superior to the conventional autocannon configuration established previously without significant design growth, and even provides major advantages over a larger deck gun.

The LMACC Design

Now that we have walked through the requirements and logic of our design, we will take a moment to provide a design summary of our baseline configuration:

- Name: USS Shrike

- Type: Patrol Ship, Guided missile (PCG)

- Cost: $96.6 million

- Displacement: 600 tons

- Length: 214 feet

- Beam: 29 feet (waterline)

- Draft: 6.5 feet

- Range: 7500+ nautical miles

- Speed: 30 knots

- two steerable, reversible pumpjets with intake screen

- Integrated electric propulsion

- Diesel engines

- Crew: 15 (31 beds)

- Armament:

- Eight LRASMs

- SeaRAM

- Seven Javelin pintle mounts

- One Javelin launch tray per mount

- Ten stored missiles per mount

- Either a M2 Browning or Mk 47 AGL per mount

- 105mm howitzer

- 36 Spike NLOS missiles

- 64 Miniature Hit-To-Kill Missiles

- COMBATSS-21 combat management system

- Latest generation full-sized AN/SLQ-32 electronic warfare suite

- Standard decoy launchers

- Excellent optical sensor suite:

- Visible Distributed Aperture System (DAS)

- IR DAS

- Visible/IR camera turret

- COTS navigation sonar

- Maximum affordable acoustic signature reduction

- Appropriate reduction of other signatures to blend into civilian traffic

- COTS navigation radar

- L3Harris Falcon III® RF-7800W non-line of sight radio

- Multifunction Advanced Datalink (MADL)

- Aft launch bay

- One 11m RHIB

- One 11m long UUV slot (multiple UUV transportation possible)

- Bay door doubles as launch ramp

- Small topside UAV storage and launch accommodations

This maintains the previously established minimum requirements while integrating the additional features discussed.

Circling back to the comparison with the hypothetical anti-ship aircraft, these low cost enhancements have added numerous advantages over the ‘adequate’ design. In addition to the previous advantages of persistence, presence, and attritability, it can now operate UUVs, transport Marines, provide surface fire support, and destroy small boat swarms. This makes the ship a much more useful platform with the flexibility to adapt to an uncertain future, and gives procurement officials a good reason to select it over the aircraft. This clear utility and economic viability is the hallmark of well-thought-out requirements, and makes this design, in our opinion, viable for American service.

It should be remembered that this information is only applicable to the baseline configuration. The other variants add a ten-foot hull segment to add special mission capabilities and will have increased costs as a result.

Automation and Manning

From a systems perspective, the core concept for this ship is that it will be built like a large USV. Since the automated systems can notify the crew when action is needed, traditional watches are unnecessary and significant crew reductions are possible. Furthermore, since the ship’s systems will be designed to operate with minimal intervention as expected of a USV, there will, in theory, be very little need for maintenance. However, there will be people on hand to correct any problems that do occur, unlike a full USV. Thus, from a systems perspective, this will allow LMACC to bridge the gap to autonomy because it keeps people on board while operating like an autonomous vessel. As such, a fleet of these ships will allow us to safely build a large body of operational knowledge and inform our approach to future USVs and human-machine teaming.

We intend to man these ships with a 15-person crew lead by a Warfare Tactics Instructor (WTI). These tactical experts will be ideally suited to lead their ships and attendant packs of unmanned vessels to victory in the most challenging circumstances, and take the initiative when cut off from external command. They will lay traps, strike targets ashore, and hunt down hostile warships while confounding the enemy’s ability to respond by vanishing into civilian traffic.

While our work indicates a crew of 15 is appropriate to manage the weapons, sensors, and drones, we are acutely aware of the uncertainty associated with this novel manning concept and the need to bring aboard additional personnel for special missions. As such, the ship has been designed with five, six-person cabins, plus a single cabin for the commanding officer, to provide ample berthing. Two of those cabins are notionally intended to be used for non-crew personnel such as Marines conducting EABO deployments, Coast Guard law enforcement detachments, or brig space. That leaves free beds for four more crewmembers with no meaningful impact, and the crew could be further enlarged by using one or both of those cabins if needed. Even in the worst-case scenario, 31 beds allow for three more crew than the existing Cyclone-class patrol ship, without hot racking. This effectively eliminates the risks associated with a smaller crew by allowing the ship to comfortably carry a traditional full complement if required.

Concepts of Operation

These ships are intended to fight forward to defend or retake island chains. The design emphasizes fighting in complex environments by disappearing into civilian traffic and littoral clutter. These ships will rely on passive sensors to complicate the enemy’s target identification problem and maximize the chance of achieving tactical surprise. The basic wartime operational unit will be a tactical pair, consisting of either two of the basic short-hull ships, or one basic design and one specialized variant. These pairs will work closely with unmanned vessels and Marines ashore to deny the area to the enemy, degrade hostile defenses, and clear the way for heavier units. They will also provide light sealift and logistics support to small, lightly equipped Marine units. Note that while we have done extensive work on tactics, deployment strategies, and cooperation with the existing leviathan navy, much of that material is not publicly releasable and will not be further discussed here. That said, much of this is built on the work of our colleague, the late Capt. Wayne Hughes, so members of the public interested in learning more are encouraged to read his work.

In peacetime, these ships will provide a cost effective asset for patrol, partnership, and deterrence missions. Since these ships are much cheaper than even frigates, they will be a better choice for countering piracy, smuggling, human trafficking, illegal fishing, and other illicit activity, allowing more expensive ships to focus on missions and training which fully exploit their capabilities. They will also enable more effective joint training with our smaller partners whose fleets are closely matched to these ships. This is particularly relevant in the South China Sea and Western Pacific where there is a need to carry foreign coast guard detachments for joint patrols and visit many small, primitive ports to reassure our friends and deter China. This will also substantially improve the readiness and performance of our fleet by reducing the workload on high-end assets, and offering early command billets to help develop young officers.

Finally, fleet integration is greatly simplified by the operational similarity of this PCG to the Cyclone-class PC. LMACC can serve as a drop-in replacement for the Cyclone at similar cost, so there is no operational risk. We could hand one of these ships to the fleet today and they’d be able to put it to work immediately by treating it like a Cyclone while the Surface Development Squadron refines the more advanced tactics developed by the Naval Postgraduate School. This makes it possible to jump immediately to serial production if desired, although building a prototype first would reduce risk at the cost of delaying its entry into service.

Ship Variants

We have plans for several special mission variants. In keeping with the Navy’s historical tradition of naming small ships after birds, they have all been given bird names. The baseline LMACC variant, the Shrike, has already been discussed, and two additional variants have been fleshed out, the anti-aircraft Falcon and the anti-submarine Osprey, both of which add new capabilities with a ten-foot hull extension.

It is difficult to discuss the details of the Falcon’s operation publicly, but it adds a new sensor and a tactical-length Mk 41 VLS module to destroy hostile maritime patrol aircraft before they can distinguish it from civilian traffic. This will protect these ships from the single greatest threat to them, hostile aircraft, and substantially improve their ability to operate within hostile A2/AD systems.

The Osprey variant, on the other hand, is relatively simple and is built to maximize the impact of USV-mounted sensors. The primary addition is eight new angled launch cells for Tomahawk cruise missiles modified to carry a lightweight torpedo. This allows a very small number of these ships to greatly improve our ability to deter and defeat submarines, since they can quickly strike targets detected by offboard sensors from hundreds of miles away. Furthermore, since Tomahawk is a well-established weapon fielded across the fleet, this will allow us to add this capability across our surface combatant fleet, and provide a way to recycle obsolete Tomahawks when we inevitably move on to other weapons. Finally, this variant is rounded out by a hull-mounted passive sonar and four fixed torpedo tubes for self-defense, since it is expected to operate in areas with elevated submarine risk.

Two additional variants have been considered. The first is a drone mothership which adds a UUV handling module to field large numbers of UUVs, and may also modify the aft launch bay to carry two boats or USVs. The second is a coast guard variant which replaces most of the missiles with a dedicated sickbay, brig, and secure contraband storage to turn it into a bigger, more capable version of the Sentinel-class cutter, although these capabilities could also be added in a hull segment if an export customer wants to retain the missiles.

Program Status

Our requirements and top-level engineering are complete. The only major task remaining is to finalize our hullform, and we can do that in parallel with shipyard and supplier selection. Almost all the technology we have selected is fielded. The remaining technologies are closely based on fielded systems, and the baseline Shrike will still be combat effective if delays force it to deploy before these technologies are ready. Since the Naval Postgraduate School is outside the traditional shipbuilding bureaucracy, we have significant flexibility in our path forward to production. We could do anything from traditional acquisition to building this under the umbrella of a research project outside all existing acquisition structures, as was done with TACPOD, so we can take whatever approach is most acceptable to Congress and the Navy.

Mr. DiDonato is a volunteer member of the NRP-funded LMACC team lead by Dr. Shelley Gallup. He originally created what would become the armament for LMACC’s baseline Shrike variant in collaboration with the Naval Postgraduate School in a prior role as a contract engineer for Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control. He has provided systems and mechanical engineering support to organizations across the defense industry from the U.S. Army Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC) to Spirit Aerosystems, working on projects for all branches of the armed forces.

Featured Image: LMACC design screenshot courtesy of Ben DiDonato