Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Drake Long

In one part of the Southeast Asian epic Sejarah Melayu, the 15th century Malacca Sultanate receives a lavish gift from the distant emperor of China, then ruled by the Ming Dynasty. The Ming Emperor sent to Malacca a ship filled with precious golden needles, one from each of his subjects, that represented not only China’s vast wealth but also the immense manpower the Emperor held at his disposal. The note accompanying the needles made it clear China had heard about the upstart Malacca Sultanate and wanted to see whether it was a potential rival by requesting tribute in kind for the Ming court that could display Malacca’s power. Much to the Ming Emperor’s surprise, Malacca sent back a ship overflowing with grains from the sago tree, with its emissary declaring that one grain represented one subject. The Ming Emperor concluded that the Sultan of Malacca clearly presided over a populous and powerful country, equal to his own. The addendum to all this is that one sago tree actually produces over a thousand grains at once. These grains, unlike golden needles, are therefore worthless.

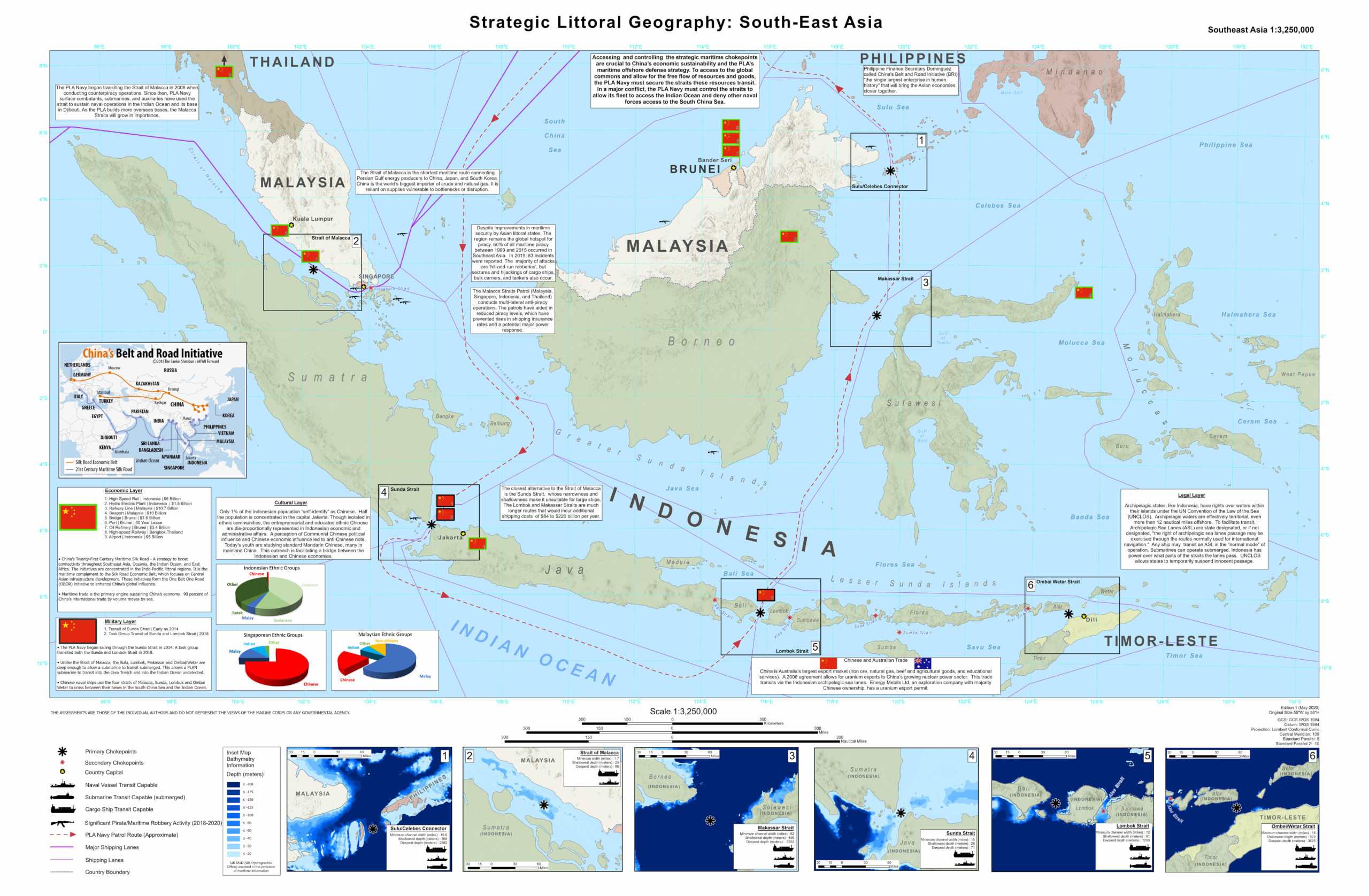

This story, while almost certainly fictionalized, illustrates an important lesson for observers watching how certain Southeast Asian states interact with China – flattery is not the same as acquiescence. But it could just as well symbolize the confidence a middling power can have when dealing with a maritime power like the Ming Dynasty, so long as it controls vital, geostrategic waterways – like the Malacca Strait. No one knew this better than the Ming, who gave defense guarantees to Malacca when the Sultanate was threatened by Siam, and whose famed admiral Zheng He frequently stopped in Malacca on his way west.

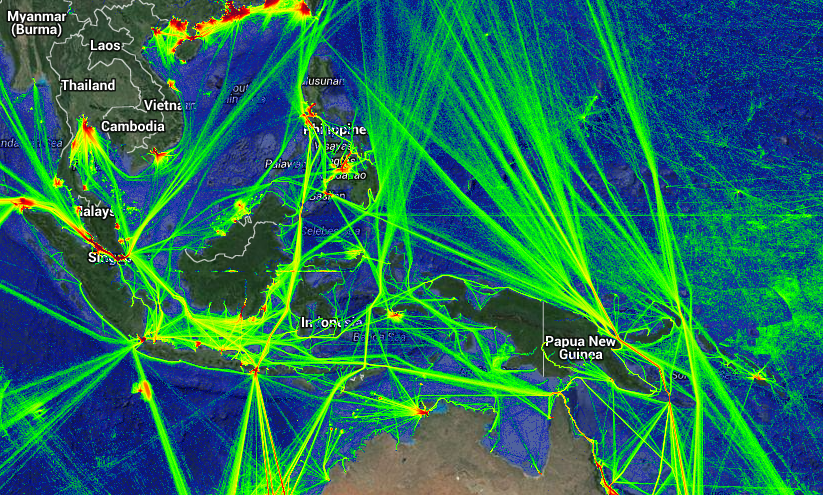

The might of a treasure fleet, or any fleet for that matter, is mitigated tremendously when the primary route for trade and transportation could be easily shut down. Stability and a cordial relationship with the controller of that chokepoint is paramount. This has not changed in the modern day. The Malacca Strait is absolutely vital to global trade – roughly 25 percent of all goods pass through it – and most any country, including China and the United States, have a vested interest in its security and openness.

The current fear of China is a U.S.-instigated blockade of the Malacca Strait that would starve China of resources and trade – described by Hu Jintao in 2003 as the “Malacca Dilemma.” China has revised its maritime strategy to reflect this. Yet an effective blockade of the Malacca Straits seems unlikely. For one, any blockade would not just affect China, but every country that trades through Southeast Asia. Those neighboring the strait would especially not want to see trade rerouted through the south of Indonesia.

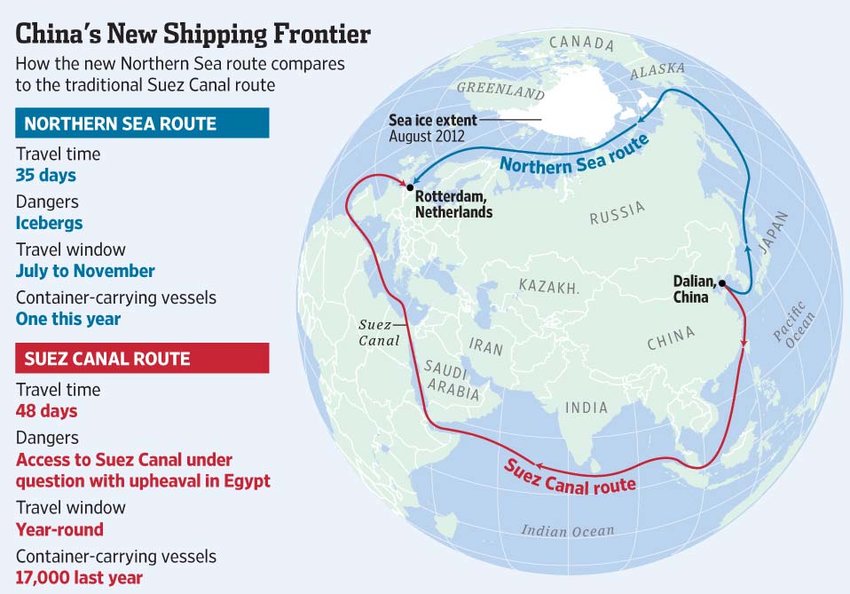

Furthermore, China is hardening itself in the event of a blockade, by seeking out other passages and methods to receive resources. The current pipeline project in Myanmar is one such way China will mitigate its dependence on the Malacca Strait. Overland routes running through Central Asian and Russian parts of the Belt and Road Initiative represent another method.

The Malacca Strait may not actually be the most likely flashpoint in a regional wartime scenario. It is increasingly likely that far from being the target of a blockade, China will be able to impose a blockade instead to isolate an American ally or the U.S. itself and weather the consequences.

However, the unique situation of Southeast Asia is that it holds numerous chokepoints, with Malacca merely being the most expedient of those connecting Southeast Asia to the Indian Ocean. What are these other chokepoints, and what value do they hold for the Chinese and U.S. Navies?

Consideration should be paid to the tail-end of the Malacca Sultanate’s reign. There was one naval power the Malacca Sultanate couldn’t stave off, even with its advantageous position. Malacca was ultimately toppled by the Portuguese Empire in the early 16th century. However, while Malacca was a prime trading post for the Portuguese, they learned the hard way about the consequences of disturbing the peace of this strategic chokepoint. Malacca’s resistance against the Portuguese continued on – but in the form of piracy, denying Portugal the ability to fully benefit from its new conquest.

Going to the present, if a modern wartime scenario pushes the U.S. Navy outside the First (and maybe Second) Island Chain, knowledge and an approach to the straits and chokepoints of Southeast Asia will be vital. No navy in Southeast Asia can operate comfortably without access to these littorals, and no presence guarding them is safe if there is anarchy or hostile actors on the coastlines. These are the areas where land-based, mobile forces can hurt enemy navies in disproportionate ways.

The Marine Corps’ Commandant’s Planning Guidance calls for the creation of “tactical dilemmas” for any enemy navy, and envisions a highly mobile, amphibious force that does not rely on safe escort into a contested area. In practice, that has meant the Marine Corps adopting long-range missile systems that can be moved quickly from shore to shore after firing. In the future, the Marine Corps will likely adapt to a wide-range of vessels, hopping from whatever is available in contested areas to become the “Stand-In Force” envisioned by the Commandant’s Planning Guidance. The chokepoints and littorals surrounding Indonesian and Philippine waters would make for excellent forward positioning for a Marine Corps stand-in force. It would provide a critical bulwark for U.S. force posture in the Pacific by facilitating access for follow-on forces from allied Australia, and access into the South China and Philippine Seas.

Thinking Like a Pirate

In the modern day, pirates exist in the strategic chokepoints of Southeast Asia. A cursory look at where piracy is most active shows how the Malacca Straits and the Sulu Sea stand out as centers for an unusual (but manageable) uptick in maritime crime over the past year. But to be clear, very few incidents meet the legal definition of piracy. Most are more accurately called armed robberies at sea, where they involve coastal attacks or petty burglary of ships in port.

The motivation for these crimes is the same no matter the definition. These chokepoints have heavy traffic in goods and oil, and economic opportunities for coastal communities are relatively scarce. The pattern of piracy throughout the region provides a blueprint for which parts of Southeast Asia are the most strategically vital and provide the best cover for groups on land to attack targets out at sea without repercussion. In the case of the Sulu Sea, the southern Philippines that adjoins it has presented major challenges for law enforcement’s surveillance and human intelligence abilities, not least because of its long-running insurgency. These characteristics kept insurgent groups such as Abu Sayyaf alive and operating transnationally up to the modern day.

In short, the nature of these chokepoints allow non-state actors like pirates to pose a plausible threat to more capable forces, and this provides a blueprint for how the U.S. Marine Corps in particular could approach the PLAN and contested areas. Consider the example of the Sulu Sea.

Around $40 billion worth of trade passes through the Sulu Sea annually, predominantly from Indonesia and Australia. There are few good alternatives to this sea when delivering goods or supplies out of certain centers of commerce and ports, which is why trade continues even when a spate of kidnappings and robberies breaks out in its waters. For Australia, the Sulu Sea is a thread connecting it to Southeast Asia, and as such it has participated in numerous joint patrols and regional anti-piracy efforts.

More pressingly, in the event of the U.S. being pushed out of the First Island Chain by force, the U.S. alliance and facilities on the territory of Australia make that country a likely staging ground for a push back into Southeast Asia’s maritime commons, or wherever the fighting may be. The route for that thrust would likely go through the Celebes and Sulu Seas in the northwest. The U.S. Marines at Darwin will find themselves at the vanguard of this push. This was previously seen during the U.S. offensive on Imperial Japan’s territories during the Second World War, preluded by the Solomon Islands campaign and the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The particular issue is China knows this as well. It is extremely likely that isolating Australia would be a paramount objective for the PLAN in any major wartime scenario, if only to coerce Australia into not hosting additional U.S. forces. This is, among other reasons, why China is pursuing the low-risk high-reward strategy of getting a base or some kind of facility to operate out of in the South Pacific. Threatening Australia’s sea lines of communication going toward Northeast Asia would be a deathblow to Australia’s economy, and narrowing its access to a regional conflict would put pressure on any U.S. and allied forces staged there.

A PLAN blockade or presence near the Sulu Sea is thus likely, as it gives China the ability to economically coerce a trade-dependent and allied maritime state like Australia. It would also keep the pressure on another U.S. treaty ally, the Philippines, whose facilities the U.S. may not even be able to use during wartime or in the beginning stages of a conflict.

However, the areas most trafficked by pirates generally have the safest littoral bases for them to operate out of, and while relevant countries have greatly stepped up their maritime domain awareness in recent years, the PLA may suffer a deficit in intelligence of what is happening beyond the coastline and within densely forested islands. “Hit-and-run” attacks would be difficult to retaliate against effectively, especially if Marine Corps vessels and vertical lift are sufficiently quick enough to lift units and their long-range precision fires out of harm’s way. In addition, borders are infamously porous in these areas where pirates operate, complicating efforts to neatly find their bases, catch them in the act, and apply pressure to their hosts.

Navy ships cannot enter the waters of these chokepoints easily – the Sibutu Passage at the southern end of the Sulu Sea is only about 18 miles wide. If the Navy keeps its distance, merchant marine and smaller vessels are easily threatened without consequence, creating something of a dilemma on when and where to intervene. Terrain knowledge of coastal areas requires knowledge of their communities, which a hostile or occupying force will not get easily or quickly, and the areas around these specific chokepoints like the Sulu Sea are veritable vacuums of information even for law enforcement agencies.

Even in a less ideal scenario, an enemy navy would need to go ashore or be bogged down in the dilemma of dealing with land-based threats to those assets necessary for surveilling the area or an effective blockade. That detracts from other objectives, and would involve a disproportionate amount of resources. Arriving to one end of the Basilan Strait, only to discover the Marines have hopped to the other end, would be immensely frustrating.

One assumption being made is that the future Marine Corps will have some unmanned surface vessels or unmanned underwater vessels as part of its toolkit for operating in a contested domain. The core capabilities of those USVs and UUVs should be ISR and communications. The disadvantage of areas like the Sulu and Celebes Seas is that Marines will face information problems as well. A superior land-based, low-risk ISR capability would lend Marines the ability to target ships at sea, but a strong HUMINT relationship with coastal communities would similarly go a long way toward eluding the enemy and operating effectively in a contested area where the U.S. Navy may be nowhere nearby. It is worth noting these same coastal communities were key to Allied ISR efforts in the Second World War.

Conclusion

The Marine Corps’ future method toward strategic chokepoints and littorals could be taking the pirate’s approach and ramping it up with new weaponry, ships, superior ISR, and tactical creativity. This is not anything regional navies are suited to deal with, and definitely not something an organization like the PLAN would be comfortable responding to given it would require flexibility and initiative at the tactical level that the command-and-control obsessed PLA does not actively nurture.

Taking piracy a bit more literally, Marines could board enemy merchant marine ships operating in the area and inflict material damage to the enemy. However, the ultimate goal for the Marines in a regional conflict where the U.S. lacks sea control will be to use land-based assets to punch a hole through an enemy navy’s sea control, and then facilitate access for a friendly navy to move onto the battlefield. In this vein, the Marine Corps will find a viable operating ground in Southeast Asia’s littorals and chokepoints.

Drake Long (@DRM_Long) is an analyst and reporter covering the South China Sea and Southeast Asian maritime issues for RadioFreeAsia. He is also a 2020 Asia Pacific Fellow for Young Professionals in Foreign Policy.

Featured Image: HAT YAO BEACH, Thailand (Feb. 28, 2020) – A U.S. Marine with Alpha Company, Battalion Landing Team, 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, sets security alongside Royal Thai Marines during an amphibious landing for exercise Cobra Gold 2020 at Hat Yao Beach, Kingdom of Thailand, Feb. 28, 2020. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Audrey M. C. Rampton) 200228-M-IP473-1063