This article was first published in the KÖMS’s journal, No. 4/2022 and is republished with permission.

By Dr. Sebastian Bruns

With its significant geopolitical, strategic and military changes stemming from Russia’s war against Ukraine, 2022 has the potential to go down in history as a true watershed year. Among many other critical developments, Sweden’s decision to apply for NATO membership constitutes another significant departure from its long tradition as a non-aligned nation.1 It is with much political fanfare that Stockholm and Helsinki are expected to join a reinvigorated transatlantic alliance that not only finds an old nemesis on its Eastern front, but also renewed American leadership in the post-Donald Trump U.S. presidency. Experts are looking in particular at what military capabilities Sweden and Finland will bring to NATO.2 This article will provide some thoughts on the Swedish Navy, what it will bring, what NATO needs from it and where some overlaps and opportunities exist.3

For starters, the Tre Kronor Navy celebrated its 500th anniversary this year. Founded in 1522, it therefore brings to the forefront a very long tradition as a sea power. If one does not follow conventional wisdom, sea power status does not depend solely on the size of a country’s navy, but also the maritime mindset of a country’s people. By way of comparison, the German Navy will celebrate its 175th anniversary in 2023, a much more modest commemoration due to Germany’s checkered naval history. Since its post-World War II rebirth, the West-German Bundesmarine and its post-Cold War successor, Deutsche Marine, have had laudable successes as alliance navies, usually operating internationally under an EU, NATO or UN mandate. The Swedish Navy might look to their example as it seeks to create a mindset that covers national, territorial and alliance defense.

If anything, Sweden’s rich naval tradition can help re-navalize NATO. The Alliance is coming off two decades of land-centric counterinsurgency, counterterrorism and state-building operations in Afghanistan, which has created an officer and political-strategic corps of continentally-thinking individuals. While Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and incursion into Eastern Ukraine began to change NATO’s mindset drastically towards more conventional aspects of deterrence and warfighting across domains, it remains very much culturally dominated by army and air force generals, despite carrying the “North Atlantic” in its name. Given the maritime component of the new era’s challenges – such as Russian undersea activity, a focus on the Arctic, Baltic, Black, and Mediterranean Seas, as well as the increasingly confrontational posture of the Chinese Navy in their Indo-Pacific backyard and beyond – it is high time for NATO to focus on the naval aspects of its members’ security.

The Swedish Navy brings to the table a wide experience in national and territorial defense at sea and in the protection of commercial shipping, two core naval missions spanning a wide spectrum. Moreover, the Swedish Navy has some experience in multilateral maritime operations, such as the EU’s counterpiracy mission ATALANTA (2010) and the UNIFIL maritime task force (2006-2007). More recent NATO accessions include former Warsaw Pact countries that had little to no joint and combined naval expertise.

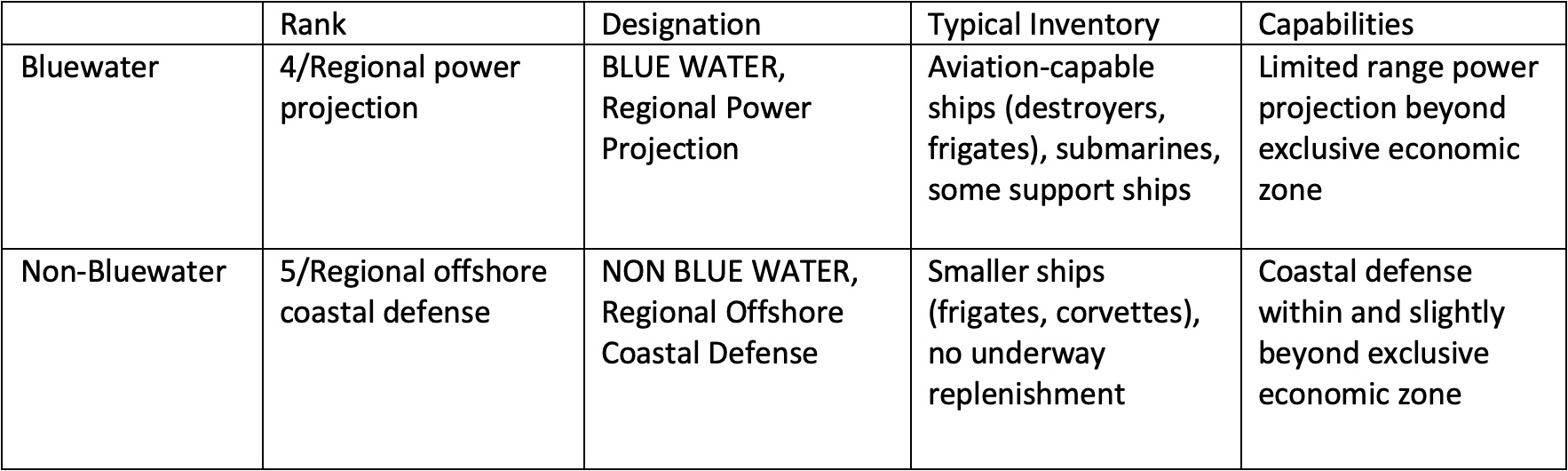

From a naval perspective, NATO is currently dominated by the large and capable navies of the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. The U.S. Navy and Royal Navy have driven naval rejuvenation in the Baltic Sea more so than NATO’s Baltic members. This is hardly surprising and should empower littoral states to follow suit, where possible.4 In addition, smaller but potent maritime powers such as Italy, Spain, France, the Netherlands and Denmark are part of the Alliance and can serve to re-focus on the maritime flanks and fronts of NATO.5 According to Geoffrey Till, noted navalist and sea power expert, the Swedish Navy could be understood as falling right between a type 4 blue-water navy, the lowest in that category, tasked with regional power projection, and the most capable non-blue water navy, a type 5 regional offshore coastal defense navy.6

While such attempts to rank navies should be taken with caution – the risk of comparing apples and oranges is real, even at sea – such conceptual undertakings offer hints at levels of ambition for a navy, as well as their potential to add to NATO’s capabilities for combined operations. At the same time, as Austrian naval doyen Jeremy Stöhs has pointed out, Western navies face a true dilemma in the accelerating quest for high-end technology and the political, operational and financial costs this incurs on small- and medium-size navies.7

A different approach for sizing up navies was offered in 1995 by naval historians Jon Sumida and David Rosenber, aptly grouped as “Five Ms”:

- Men (and Women), or the naval personnel;

- Machinery, or the types of ships, aircraft and other vehicles that navies employ;

- Management, or the type of command structure as well as the political framework that shapes a navy’s roles and missions;

- Money, or the kind of funding into navies which, at the core, are long-term supply-based financial investments rather than demand based;

- Manufacturing, or the industrial base in a country to sustain a navy.

In 2000, the late German naval historian Wilfried Stallmann added a sixth “M”: Mentality, or a navy’s strategic culture.8 A more contemporary and potentially more quantifiable approach would look at the size and nature of the fleet, its geographic reach, its functions and capabilities, its access to high grade technology, its reputation and the technological excellence it provides. While an in-depth discussion of these aspects is beyond the scope of this article, the technological excellence that Sweden can potentially bring to NATO and its navies is worth a closer look.

The Swedish naval capability contribution covers four notable assets, including small combatants, amphibious boats, and forthcoming submarines and signals intelligence ships.

The Visby-class corvettes are a sleek and capable class of ships that are optimized for Sweden’s rugged coastlines. Their low radar signature can help “hide” them from enemy sensors. They will provide assets to the Standing NATO Maritime Groups that operate in the Baltic and Northern flank area, lending much needed credibility to NATO’s littoral components. Last but certainly not least, their very modern design, which one hopes will be continued somewhat in a prospective successor class, serves to display the technological superiority that NATO member states’ shipyards can churn out. Navies, which often operate “out of sight, thus out of mind,” need to impress upon their peoples their role to create the critical support for such long-term investments. Short of frigates, corvettes like the Swedish ones could be interesting for other Baltic littoral states that do not yet operate such medium-sized warships.

Sweden’s amphibious assault element, in particular the CB-90 fast boats, which have garnered interest around the Baltic littoral states (e.g. in Germany), is another worthwhile contribution to the alliance and the Northern flank. Amphibious warfare has gained significant attention in the Baltic Sea, whether through pre-2022 Russian Navy drills, allied amphibious elements operating as part of the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), or repeated visits by the U.S. Navy’s USS Kearsarge (LHD-3) amphibious readiness group this past summer. While the big decks represent the high end of amphibious warfare, Baltic littoral states and NATO should train and exercise offensive and defensive small boat operations from the sea as well.

Finally, two technological features that are not yet in the water. First, the future Swedish A-26 submarine – an ambitious project for a next generation undersea capability – is likely to be a contender for NATO’s preferred non-nuclear boat. ThyssenKrupp MarineSystem’s air independent propulsion submarines (type 212A/CD) remain the challenger, while the Netherlands and others look for a proper model for their force regeneration. A more competitive market ought to help NATO member states in general, though Kockums has not built an indigenous submarine in more than 25 years. To their enduring credit, Swedish submarines continue to have a high standing in the United States, due in part to its lease of HSwMS Gotland from 2005-2007. Another asset that still has to prove its viability is the future HSwMS Artemis, a signal intelligence ship that is currently two years overdue amidst the reverberations of the pandemic as well as major hick-ups in this Swedish-Polish joint venture.

With its rich partnership with NATO navies, Sweden will be well placed to get underway. NATO navies, whether on individual and national deployments or as part of rotational Standing NATO Maritime Groups (SNMG), are a significant presence in the Baltic Sea. NATO operates two of these standing groups in the Northern European area of operations, a larger surface ship group (SNMG 1, the former Standing Naval Force Atlantic, STANAVFORLNT), and a mine countermeasures group (SNMCMG1, the former Standing NATO Force Channel, or STANAVFORCHAN, and Mine Countermeasures Force North Western Europe, or MCMFORNORTH, respectively) grouped around smaller surface combatants and tenders.

The Swedish Navy, upon gaining the operational prowess and formal legitimation to integrate, could dispatch one or more of its warships into the groups. At the same time, exercises such as the annual Baltic Operations (BALTOPS) and Northern Coasts (NoCo) will provide ample opportunity to train with other NATO navies in a joint and combined effort. NATO will likely require the Swedish Navy to account for regular but flexible naval presence as well. This should come as no surprise for Sweden given its frontline statues in the Baltic Sea, and it should use every opportunity to work with other NATO navies. A broader mindset, keeping in mind the military, constabulary and diplomatic use of the sea by navies,9 should yield a dedicated national naval or maritime strategy that addresses some of the trajectories outlined above.

It remains unclear whether NATO’s own “Allied Maritime Strategy,” published in 2011, will be rewritten – the need for which has been addressed in public forums repeatedly.10 In light of this, and absent a top-down effort, a bottom-up strategic effort would be very welcome by allied navalists. This ought to include some dedicated investments in the military-intellectual complex as well, given the need to study, research, advise, critique and explain naval matters to counter the infamous, often diagnosed “sea blindness.”

NATO, at least in the Baltic Sea and along its northern flank, is looking for cooperation agreements and a concurring mindset, not necessarily commands. There is much activity in the Baltic Sea in the latter field, and the Swedish military – already likely to be challenged to fill NATO billets around Europe and in North America – will be stretched to cover both staffing and operational requirements. Germany, for instance, is pushing hard for formats that attempt to offer new command, control and coordination functions in the Baltic Sea area, triggering some envy in other member states and the real risk of over-complicating NATO’s effectiveness in the region.11 Advanced Swedish-Finnish naval integration in recent years might offer a unique opportunity for true burden-sharing of two smaller militaries in NATO, and a chance to revive allied pre-2014 pooling and sharing initiatives in a meaningful way.

With the accession of Sweden and Finland into Norway, one discussion likely to resurface is whether or not the Baltic Sea is a “NATO lake.” As Hamburg-based Baltic Sea expert Julian Pawlak has rather brilliantly put it, “Designating the Baltic Sea as a ‘NATO lake’ is fatal in many ways. Besides the fact that, following such logic, it would already have been an ‘EU lake’ for some time, the use of the term suggests that the Baltic could be handled more or less exclusively by NATO, as an inland sea (which it almost is, politically), leading to the subsequent fallacy of complete sea control (which is certainly not the case).12 Sea strategists know that maritime territory can and will never be controlled in a manner that militaries do on land. In addition, if history is any guide, places such as the Mediterranean and the Atlantic have at one point been designated as NATO lakes – until they no longer were, with the incursion of then-Soviet submarines and naval assets in the Cold War and more recently by the aspiring Chinese Navy.13

Baltic navies would be well advised not to close or cordon off seas, and countries such as Germany have gone a long way to conceptualize that the Baltic Sea is intimately connected to the more contested and to the rest of the globe. Legal and etymological concerns aside, Baltic navies will still have to exercise sea control and all forms of naval warfare on the whole spectrum of conflict. A self-serving description of the Baltic as a “NATO lake” amounts to detrimental whistling in the woods at best, or wishful thinking and the willful degeneration of naval strategic thought and practice at worst.

The Swedish Navy can and must play an important role in the Alliance, and it should be encouraged to infuse its professionalism and maritime strategic culture into NATO, as well as identify partners with which it can aggressively pursue bilateral and multilateral programs so that NATO as a whole can be strengthened. Given existing formats, examples could be joining the German-Dutch amphibious cooperation to make it tri-partite, participating in the German-Danish-Polish (though for the time land-focused) Multinational Command East (MNC E) in Szczecin (Poland), offering its next-generation light corvettes/light frigates to partner navies, etc. Finally, the Swedes would also be well advised not to overstretch and avoid making the same mistakes as their soon-to-be fellow allies have done with regards to atrophying naval power in favor of a diffuse land power argument. Balancing national and alliance defense with international crises management remains the key challenge of the day for those wearing the uniform with the Tre Kronor.

Dr. Sebastian Bruns is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Security Policy Kiel University (ISPK), where he served as the founding father of the adjunct Center for Maritime Strategy & Security, 2016-2021. From 2021-2022, he was the inaugural McCain-Fulbright Distinguished Visiting Professor at the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland (USA). Since 2021, he is also a Senior Associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC, and a Corresponding Fellow at Kungl. Örlogsmannasällskapet (KÖMS).

[1] At the time of writing, NATO member states’ parliaments are still in the process of deliberating the Swedish (and Finnish) requests. Two countries – Turkey and Hungary – are still in the decision-making process.

[2] For a broader and more operational discussion on the military issues, see John R. Deni, “Sweden and Finland are on their way to NATO membership. Here’s what needs to happen next.” Atlantic Council Issue Brief, 22 August 2022.

[3] This essay is based on the author’s Royal Swedish Society of Naval Sciences’ inaugural lecture, given on 24 August 2022 at the Swedish Maritime Museum, Stockholm.

[4] See, for instance, Sebastian Bruns, “From show of force to naval presence, and back again: the U.S. Navy in the Baltic, 1982–2017,” Defense & Security Analysis, Taylor & Francis Journals, vol. 35(2), pages 117-132, April 2019; Bruce Stubbs, “US Sea Power has a Role in the Baltic,” USNI Proceedings, Vol. 143/9/1,375, September 2017.

[5] For a discussion of the evolution of European naval power since 1990, see Jeremy Stöhs’ study, The Decline of European Naval Forces. Challenges to Sea Power in an Age of Fiscal Austerity and Political Uncertainty, USNI Press: Annapolis, MD 2018. Sweden is covered on pp. 161-167.

[6] See Geoffrey Till, Seapower. A Guide for the 21st Century. 4th edition, Routledge: Milton Park, New York 2018, p.147ff.

[7] Jeremy Stöhs, “How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge,” Center for Military Studies University of Copenhagen, 2021.

[8] Cited in Sebastian Bruns, US Naval Strategy and National Security. The Evolution of American Maritime Power, Routledge: Milton Park, New York 2018, p. 32f.

[9] See “Triangle on the Use of the Sea,” based on Ken Booth (1977) and Eric Grove (1990), and vastly expanded, cited in Till, Seapower, p. 362.

[10] See Kiel International Seapower Symposia 2018 (on allied maritime ends), 2019 (on means) and 2021 (on the ways). Reports on each conference can be obtained through www.kielseapowerseries.com. For more in-depth coverage on current issues that should drive an alliance-wide rework of its maritime strategy, see Julian Pawlak/Johannes Peters, From the North Atlantic to the South China Sea. Allied Maritime Strategy in the 21st Century, Nomos: Baden-Baden 2021 (=ISPK Seapower Series, Vol. 4).

[11] Edward Lucas, “Close to the Wind. Too Many Cooks, Not Enough Broth,” Center for European Policy Action (CEPA), 9 September 2021.

[12] Julian Pawlak, “No, Don’t Call the Baltic a ‘NATO Lake’”, RUSI Commentary, 5 September 2022. For a counter position, see Edward Lucas, “The Baltic Sea Became a Nato Lake,” Finnish Business and Policy Forum – EVA, 27 June 2022.

[13] For use of the term “NATO lake”, see Christina Lin, “The Dragon’s Rise in the Great Sea. China’s Strategic Interests in the Levant and the Eastern Mediterranean,” in Spyridon N. Litsas, Aristotle Tziampiris The Eastern Mediterranean in Transition: Multipolarity, Politics and Power, Routledge: London 2015.