By Lieutenant Commander Gerie Palanca, USN

“The essential foundation of all naval tactics has been to attack effectively by means of superior concentration, and to do so first, either with longer-range weapons, an advantage of maneuver, or shrewd timing based on good scouting.”—Captain Wayne P. Hughes, U.S. Navy

Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt states in his 2020 Proceedings article that by 2035 the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) will have approximately 430 ships. Former Pacific Fleet Chief of Intelligence, Capt. (ret.) Jim Fanell called the span between 2020 and 2030 a “decade of concern” – Chinese Communist Party leaders likely assess 2030 as their last opportunity to militarily “reunite” Taiwan and mainland China. By that time the PLAN fleet will dwarf the estimated U.S. Navy fleet size of 355 ships. This imbalance in fleet size will likely embolden China’s regional efforts to deny American presence within the 9-dash line, China’s territorial claim in the South China Sea. By 2035, the PLAN will not only have a larger maritime force, but they will also procure anti-surface weapons and supporting capabilities that will either match or outshine U.S estimated capabilities. To characterize this scenario, the Congressional Research Service report on precision-guided munitions highlighted that the current anti-access/area denial weapon systems deployed along China’s coast and afloat outrange U.S. weapon systems, with ranges of almost 1000 nautical miles, creating a need for U.S. ships and aircraft to engage the adversary at longer ranges in order to maintain survivability. According to Fleet Tactics, increasing a weapon’s range squares the scouting (i.e. intelligence) requirement for that system.1

This exponential growth in the need for scouting to support fires is underscored in the congressional report on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) design for great power competition (GPC). The report describes the need for a system that embraces disruptive technology and the importance of operational integration, specifically in the form of “sensor-to-shooter.” For the U.S. to maintain its information advantage and dominate in a long-range fight, the military will need to adopt an information warfare approach that is rapid enough to operate within the adversary’s decision cycle. To achieve this effectively, the U.S. will need to find, fix, and disseminate targets to the warfighter at a speed far greater than ever before.

In 2020, Vice Admiral White, Commander Fleet Cyber Command, emphasized that the Navy Information Warfare Community (NIWC), including the Naval Intelligence Community, must provide warfighting capabilities enabling precision long-range strike and the community must normalize these critical capabilities with urgency. GPC has added a dimension that has created a greater requirement to support the tactical decision makers executing these fires. With the adversary’s adoption of long-range weapons to combat U.S. carrier strike groups, the decision space and tempo of traditional ISR is obsolete.

In the long-range fight, rapid, actionable, targetable information is now the center of gravity. For the NIWC to execute an ISR construct that supports this evolving nature of warfare effectively, the community will need to develop a tailored artificial intelligence (AI) capability. Scouting in support of maritime fires is a culture shift for the NIWC, but it is not the only change that needs to happen. For over a decade, NIWC has been primarily focused on either supporting the Global War on Terror and combating violent extremist organizations or tracking global civilian shipping. While these focused efforts have been immensely important, it is time for a pivot.

GPC with China may depart from previous examples, such as the Cold War, by resulting in an open conflict between great powers. An escalation with China would involve weapon systems that are designed to engage the adversary at greater than 1000 NM. This paradigm is not new, with the Navy’s reliance on the BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missile since 1983, but future attacks against unplanned, mobile targets at that range, while at risk of the adversary’s long-range anti-ship ballistic and cruise missiles is an altogether novel and unfamiliar challenge.

To address this issue by 2035, the NIWC will need to regain information superiority. Rapid acquisition of realistic AI will be only one of many tools required to accomplish this. The NIWC will need swift development of doctrine and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to execute AI-supported intelligence and modern support to precision long-range fires. Additionally, there will not be any need for new TTPs that do not address the high-end fight. The NIWC will need to support rapid acquisition of the capabilities it needs to fight tonight.

Speed up the decision cycle by defining the role of the analyst in a world of mature AI

The director of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) stated that “if trends hold, intelligence organizations could soon need more than eight million imagery analysts to analyze the amount of data collected, which is more than five times the total number of people with top secret clearances in all of government.” The DoD noticed this trend and established the Joint AI Center to develop products across “operations intelligence fusion, joint all-domain command and control (JADC2), accelerated sensor-to-shooter timelines, autonomous and swarming systems, target development, and operations center workflows.” Under these architectures, AI is the only technological way that the IC, and NIWC, will be able to use all the data available to support the warfighter in precision long-range fires.

AI is a force multiplier for the NIWC, and the integration of the technology is a matter of when, not if. The NIWC must identify the role of the operator and analyst when augmented with AI. According to the 2019 Deloitte article titled “The future of intelligence analysis,” the greatest benefit from automation and AI blooms when human workers use technology to increase how much value they bring to the fight. This newfound productivity allows analysts to spend more time performing tasks that have a greater benefit to the NIWC, instead of focusing on writing detailed intelligence reports or spending twelve hours creating a daily intelligence brief. If nurtured and trained now and over the next decade, by 2035 AI will have the ability to make timely, relevant and predictive briefs for commanders, freeing analysts to provide one of those most valuable analytical tools: recommendations.

Since AI is inextricably linked to the rapid analytic cycle required to enable long-range fires, the NIWC needs to determine the ideal end state of the analyst-AI relationship. One of the biggest misunderstandings about AI in the IC is the fear of losing the intelligence analyst. The opposite is more probable: the IC will fail to incorporate and use AI to its fullest potential to solve its hardest problems. As AI matures, the NIWC will need to integrate AI afloat and ashore to allow analysts to focus on tracking hard targets, elevating predictive analysis, and collaborating across the strike group and IC, while communicating the results effectively to the warfighter.

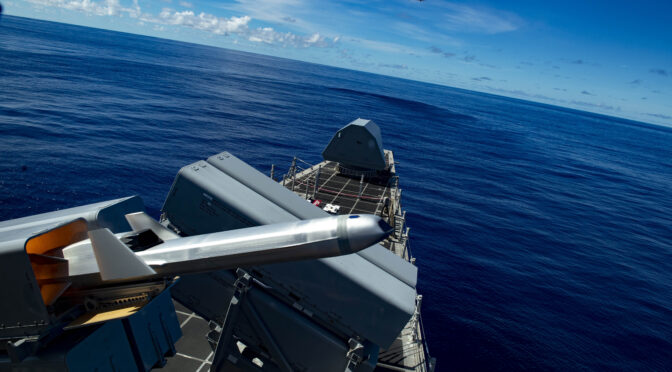

The advancement of AI alone will not ensure the NIWC’s success in conflict. The process and outputs of intelligence must be refocused to effectively enable fires and fully integrate into operations. The Navy and Air Force have also both heavily invested in the smart, network-enabled AGM-158 Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile and the Navy and Marine Corps have invested in the RGM-184 Naval Strike Missile. With the estimated flight times of these vehicles as a matter of minutes, coupled with their impressive ranges, target intelligence generated by non-organic sensors must get directly to the end user. The IC provides a majority of target intelligence to the warfighter and is woefully unprepared for this new paradigm. The IC needs to embrace a fully informed, holistic intelligence picture for the DoD to effectively execute a long-range fight in GPC. These advanced weapons also require machine speed intelligence to keep up with the timeline of engagement and the pace of dynamic targeting. Machine-to-machine systems are not new in the DoD, but AI is the avenue connecting those systems to modern missions. Because of traditional hurdles due to stovepipes and information security, the IC and DoD have the arduous chore of ensuring AI does not become an empty technology hindered by issues of classification and policy, ultimately minimizing the inputs into the algorithms. AI is also idealized as the savior of all hard intelligence problems. The NIWC needs to use AI for what it can actually do now. To that point, the IC is the key player in ensuring the NIWC has the data it needs to develop this capability.

Speed up the development of doctrine

For the NIWC, operating alongside AI and supporting precision long-range fires are doctrine gaps. In GPC the most important intelligence will be actionable intelligence with the fight progressing at a tempo where information must be available directly to the shooter and provide confidence in the target within seconds to minutes. Not to mention, the target will most likely be well outside of any organic sensors of the distributed platforms. The NIWC is not famous for disseminating information within seconds to minutes directly to the warfighter, but the right doctrine will enable this construct. This doctrine must be developed rapidly, meet the needs of the future war, and be promulgated to the Fleet for feedback based on the environment.

According to JP 1-02 DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, doctrine is the fundamental principle that guides the actions of military forces or elements thereof in support of national objectives. The national objectives in this case are decision superiority and LRF. These require a culture shift away from intelligence support to military operations towards intelligence-driven operations. This culture is not new. An example can be seen through the effectiveness of special operations forces (SOF). In the SOF community, intelligence is the foundation of the mission plan and deliberately phased execution. To tackle this modern adversary in a dynamic maritime environment, we need to adopt this culture. Within the SOF skillset, GWOT-type targets were time sensitive targets of opportunity. The intelligence team supporting these targets needed rapid processing and dissemination so the operators could engage on a compressed timeline. While cutting-edge technology played a part, the culture was the clear distinction from traditional intelligence operations. New doctrine needs to be developed to support and sustain this large culture shift within the NIWC for intelligence driving long-range fires.

In addition to a culture shift, pushing the authority to engage targets down to lower levels will enable the speed required for decision superiority and LRFs . The PROJECT CONVERGENCE exercise, the Army’s contribution to the JADC2 joint warfighting construct, highlighted that improvements must be made in mission command and command and control (C2) . These improvements can be technology-based, but many modifications can happen at the TTP and doctrine level. To make this possible, the NIWC will have to develop TTPs within battlespace awareness, assured C2, and integrated fires that inform, ensure, and synchronize mission command in precision long-range fires. Doctrine is how the NIWC will standardize this tradecraft, allowing ashore C2 and afloat mission command even in a contested environment.

While these sound like simple changes, those in the doctrine community may not be comfortable with rapid doctrine development and dissemination, especially on topics that are continually evolving like intelligence collaboration with AI and IW support to precision long-range fires. The risk of incomplete and insufficient TTPs on nascent capabilities is real for the warfighter. Unfortunately, there are countless anecdotes of systems delivered to platforms without proper doctrine and training for the sailors to be able to use or integrate the systems into current operations. With the ability to win in a GPC fight hanging on the ability to rapidly integrate emerging and disruptive technology into present operations, the NIWC cannot operate without doctrine any longer nor can it wait for the archaic doctrine process to catch up.

Speed up the acquisition process

VADM White prioritized delivering warfighting capabilities and effects as the third goal for Fleet Cyber Command. Specifically, delivering warfighting capabilities that enable movement, maneuver, and fires using emerging concepts and technologies. A rapid acquisition culture allowing for risks is the only way to achieve VADM White’s desire for persistent engagement that will allow the USN to compete during day to day operations, especially in support of holding the adversary at risk via long-range kinetic capabilities.2 This concept raises a concern that speed should not be the only goal post. The NIWC needs to ensure that it buys what is needed for the future war. If it buys the programs that are in the process now, but faster, it might not actually solve any problems. It must create a culture that is able to let go of programs that do not meet the growing threat. The NIWC also needs a strategy that integrates with the joint warfighting concept for supporting precision long-range fires.

According to the Director of the Space Development Agency, Dr. Derek Tournear, during the Sea-Air-Space 2020 Modern Warfighter panel, U.S. adversaries execute an acquisition timeline of about three to five years at the longest. By contrast, the U.S. acquisition cycle is about 10 years at the shortest. While this comment was space systems-focused, the reality rings true across the DoD acquisition system. This means a capability gap between the U.S. and an adversary will be short lived. Dr. Tournear also highlighted that this issue is not particular to the DoD acquisition program, but is a culture and process issue within the acquisition community. The DoD acquisition community is currently designed around not taking risks and overdesigning any issues that could impact program progress. A technique to combat this culture issue would be iterative designs that embrace 80% solutions on compressed time scales allowing feedback loops. Getting something to the fleet that addresses today’s problems without having to wait for full deliveries would drastically increase lethality, while real-world operator feedback would improve the end-state acquisition delivery. This is one example solution to address this problem that would complement other solutions such as digital acquisition and open architectures.

Conclusion

The NIWC has been a cornerstone of every decisive point in every major naval battle in history. Despite this pedigree, GPC has placed an exciting challenge on the NIWC. To deter and win a GPC fight in 2035 and beyond, the NIWC must evolve to meet the challenge. To embrace the problems of the future, the NIWC must build a force that can integrate with the most important disruptive technologies like AI, train the force to quickly integrate and employ those technologies, and to acquire those technologies at the right pace.

LCDR Gerie Palanca is a Cryptologic Warfare Officer and Information Warfare – Warfare Tactics Instructor specializing in intelligence operations and maritime space operations. His tours include department head at NIOC Colorado, signals warfare officer on USS Lassen (DDG 82), and submarine direct support officer deployed to the western Pacific. LCDR Palanca also attended the Naval Postgraduate School and received a M.Sc. in space system operations.

Endnotes

[1] CAPT W. P. Hughes, RADM R. P. Girrier, and ADM J. Richardson. Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations 3rd Edition, US Naval Institute Press. 2018. Annapolis, Maryland.

[2] Congressional Research Service. “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Design for Great Power Competition,” 04 June 2020. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46389.

Featured image: USS Gabrielle Giffords (LCS 10) launches a Naval Strike Missile (NSM) during exercise Pacific Griffin. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Josiah J. Kunkle/Released)