By W. Alejandro Sanchez

In late January, the Peruvian Navy commissioned its newest training vessel, the BAP Union, which will train future generations of naval cadets. This brand new ship is an ideal starting point to discuss the vessels utilized by Latin American navies to instruct their cadets. As any sailor knows, there is no replacement for hands-on experience aboard a vessel to train future naval officers and personnel.

Latin American navies understand this fact, hence, training vessels regularly carry out voyages in which they visit several international ports. These multinational trips fulfill two purposes: to train cadets and serve as floating ambassadors in order to develop friendly relations between navies and nations.

A Comprehensive List

We will begin our discussion by briefly listing the numerous training vessels that Latin American navies possess. Apart from the Union, the region’s newest training ship, other vessels include Argentina’s ARA Libertad, Brazil’s NVe Cisne Branco and the NE Brasil, Chile’s B.E. Esmeralda, Colombia’s ARC Gloria, Ecuador’s BAE Guayas, Mexico’s ARM Cuauhtemoc, Uruguay’s ROU Capitan Miranda and Venezuela’s ARBV Simon Bolivar. Since an in-depth discussion of every Latin American training vessel would require a comprehensive report, we will focus on providing some general remarks.

First, a quick overview of these vessels finds a strong influence from Spanish shipyards. The Peruvian state-controlled shipyard SIMA (Servicios Industriales de la Marina) constructed the Union in its shipyard in the port of Callao, but the Spanish company CYPSA Ingenieros Navales cooperated in the vessel’s structural design. As for other ships, many were constructed by Spanish companies. For example Colombia’s Gloria, Ecuador’s Guayas, Mexico’s Cuauhtemoc, and Venezuelan’s Simon Bolivar were all manufactured by Astilleros Celaya S.A., while Chile’s Esmeralda was obtained from the Spanish government which constructed it at the Echevarrieta y Larrinaga shipyard in Cadiz. One exception to the rule is Brazil’s Cisne Branco, which was constructed by the Dutch company Damen Shipyard.

Second, these vessels are all masted ships unsurprisingly. Without getting into detailed specifications, it is worth noting that the Mexican Cuauhtemoc has three masts (for a grand total of 23 sails) while Argentina’s Libertad has three masts and 27 sails. Finally, Peru’s Union, has four masts, making it the biggest regional training vessel. There is one vessel that is without masts, the Brazilian Brasil, which is a modified Niteroi-class frigate.

Finally, cadets also board warships as part of their training. For example, Colombian cadets from the “Almirante Padilla” naval school have taken a trip aboard the frigate ARC Antioquia to further their instruction.

Training At Sea: A Confidence Building Mechanism

Training vessels have a diplomatic and confidence building component to their voyages. Most of their trips include stops in various international forts, turning these vessels into ambassadors at sea of their respective nations.

For the sake of brevity, we will mention a couple of recent itineraries. Mexico’s Cuauhtemoc is carrying out an ambitious 205-day voyage in which it will dock in 17 foreign ports in 13 countries (the cruise is known as “Ibero Atlantic 2016”). The vessel docked in New London, Connecticut, from 2-6 May and during the visit, Mexican cadets “interact[ed] with their counterparts at the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London as well as visit[ed] Naval Submarine Base New London in Groton.” Meanwhile, in mid-May the Colombian Gloria returned to the Barranquilla port after a 41 day cruise through the Caribbean, where it visited Castries, capital of Saint Lucia, and Roseau, capital of Dominica.

Training vessels have also carried out ambitious projects, namely sailing around the world. For example, in August 1987, the Uruguayan Capitan Miranda, set sail in a trip around the world, a feat that was accomplished in 355 days. More recently, Ecuador’s Guayas arrived home in early March after a similar voyage that required 295 days to complete.

Another element of confidence building is how foreign naval officers are often invited to take part in some of these cruises. For example, a 2015 multinational trip by Colombia’s Gloria had officers from Brazil, Peru, and Uruguay aboard. Similarly, Venezuela’s Simon Bolivar left port in mid-May for its “Europa 2016” expedition. Accompanying the over 100 Venezuelan cadets aboard are naval personnel from Bolivia, Brazil, Dominican Republic and Uruguay.

Venezuela’s training vessel has a very appropriate nickname: “The Ambassador Without Borders” (“El Embajador Sin Frontera”), which can also be applied to the training vessels of other nations. These are floating embassies that bring together the multinational crew as well as showcasing the best a country has to offer at every port call.

Incidents

It is worth mentioning that when vessels are outside of their nation’s territorial waters, some bizarre and tense situations can occur. A clear example is what happened to Argentina’s Libertad, which has to do with the country’s economy. For the past decade and a half, the South American nation has dealt with crippling debt due to owing various shadowy corporations known as vulture funds. After many negotiations and court rulings, Argentina paid USD$9 billion to these entities in April.

This financial situation has ramifications with the training vessel because in October 2012, the Libertad made a port call in Ghana. Unfortunately for the crew, the ship was not allowed to depart because the Ghanaian government received a request from a hedge fund called NML Capital Limited to detain the vessel, as a sort of partial repayment for the Argentine government’s debt. The Libertad would then stay in the Ghanaian port of Tema until mid-December, when the Argentine government secured its release (the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled on the side of Buenos Aires). The ship docked in Buenos Aires in January 2013.

This past April, the Libertad left for a new expedition. Prior to its departure, President Mauricio Macri gave a speech from the vessel’s deck, where he stated that “today we have normalized our relations with the world, today you can depart in peace, because this will not occur again.”

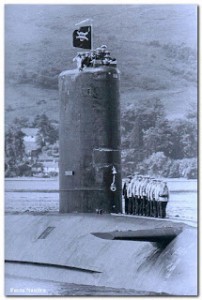

Other vessels have gone through more potentially violent situations, namely when they crossed the Gulf of Aden en route to the Indian Ocean, an area known for pirates that operate out of the Horn of Africa. In 2008 Chile’s Esmeralda crossed the region, and it took measures to prevent an attack, including deploying 30 men on deck armed with rifles and grenade launchers. Ecuador’s Guayas passed the same area this past October 2015, and armed troops were also assigned on deck in case pirates appeared. So far, there have been no reported incidents of training vessels being attacked.

Upgrades Needed?

Unsurprisingly, one problem is the generally advanced age of these ships. For example, the Colombian Gloria was commissioned in 1968, a decade later Ecuador received the Guayas (in 1977) while Venezuela commissioned the Simon Bolivar in 1980. But it is Uruguay that can be proud of having the oldest training vessel still in service in Latin America as the Capitan Miranda was launched in 1930. The vessel was originally constructed as a hydrographic ship at a Spanish shipyard, and was transformed into a training vessel in 1977. The ship carried out its first training voyage the following year. Prior to Peru’s Union, the region’s newest ship would be Brazil’s Cisne Branco, which was launched and assigned in 2000.

In other words, most Latin American navies could profit from a new training vessel. One obvious example is the almost-century old Capitan Miranda, which could be turned into a floating museum while the Uruguayan Navy obtains a new ship. The vessel was already upgraded in 1977 and 1993 and it has been in a dock since 2013 as the Navy carries out a new overhaul to increase its lifespan.

Budgetary issues and other security priorities are the obvious main hindrances to regional navies acquiring new training vessels. For example, the Uruguayan Navy is currently undergoing a transformation as it plans to purchase as many as three OPVs (probably from the German shipyard Lurssen) to patrol its EEZ, which would be the country’s biggest platform acquisition in decades. The deal is rumored to cost USD$250 million, a major investment for a small country. As for other navies, they are also focused on acquiring new platforms. Case in point, Colombia acquired two (used) German submarines, which arrived in 2015, while Mexico’s state-run shipyard ASTIMAR (Astilleros de la Secretaria de Marina) is currently constructing Damen OPVs in its shipyards. For the time being, it seems that no new training vessels will be constructed.

Final Thoughts

While new naval platforms are necessary to patrol any maritime territory, there is an obvious problem in continuing to use dated equipment to train a Navy’s future officers. Peru and Brazil’s new training vessels are positive developments, but this pattern will probably not be followed by other Latin American states in the near future.

Certainly, it could be argued that as these aging vessels are still operational, it is not imperative to replace them – case in point, the almost-century old Capitan Miranda. However, repairing these ships to extend their lifespan will only get costlier and more time-consuming as time progresses, hence alternative plans should be drafted.

After all, these vessels are important diplomatic tools as they travel different regions of the world, essentially becoming naval ambassadors given their friendly international port calls, which foster positive relations. Moreover, while it is important for any country to possess modern platforms, i.e. OPVs or even a nuclear-powered submarine, ultimately these are machines that need well-trained officers to control and guide. Voyages in training vessels are only one aspect of a naval officer’s education and career, but they are a critical component. It is only logical that naval cadets should have the best training equipment possible in order to become the best officers possible.

W. Alejandro Sanchez is a researcher who focuses on geopolitical, military and cyber security issues in the Western Hemisphere. Follow him on Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

The views presented in this essay are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated.

Featured Image: B.E. Esmeralda of the Chilean Navy. Photo: Armada de Chile.

el

el  other side of the Atlantic, the

other side of the Atlantic, the