By Nicholas Romanow

In the Indo-Pacific and beyond, almost every speech, strategy document, and think tank report mentions “allies and partners” as a critical element of American national security. The military’s culture is organized around warfighting, a concept that may not immediately bring the criticality of allies and partners to mind. When officers in the sea services sit down to discuss big strategic issues, conversations more often center on the strengths and weaknesses of our adversaries, while any assessments of our allies come as an afterthought.

Service members are often told that their first and foremost obligation is to be “warfighters.” This mindset is certainly useful because it calls sailors to meet the highest standards of the Navy’s core values and fulfills the first objective clause of the mission of the Navy: “to win conflicts and wars.” Yet such a mentality neglects the other essential half of the mission statement: “while maintaining security and deterrence through sustained forward presence.” The Navy’s mission today—and over the near and long-term—cannot be achieved by solely focusing on fighting wars; the Navy is uniquely positioned to strengthen U.S. alliances and contribute to this essential pillar of American grand strategy.

Alliances at Sea from Mahan to NATO

The sea services’ reliance on allies is rooted in the Mahanian tradition of American strategic thought. Mahan originally argued that colonies were the most reliable resource for sustained sea power.1 Today, alliance sustained by the forward-presence of the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard have been beneficial for many countries besides the United States, especially the export-driven economies of East Asia, by guaranteeing the freedom of navigation that enables global commerce. The economic success of America and its allies also proves Mahan’s broader thesis that maritime dominance enables national prosperity.

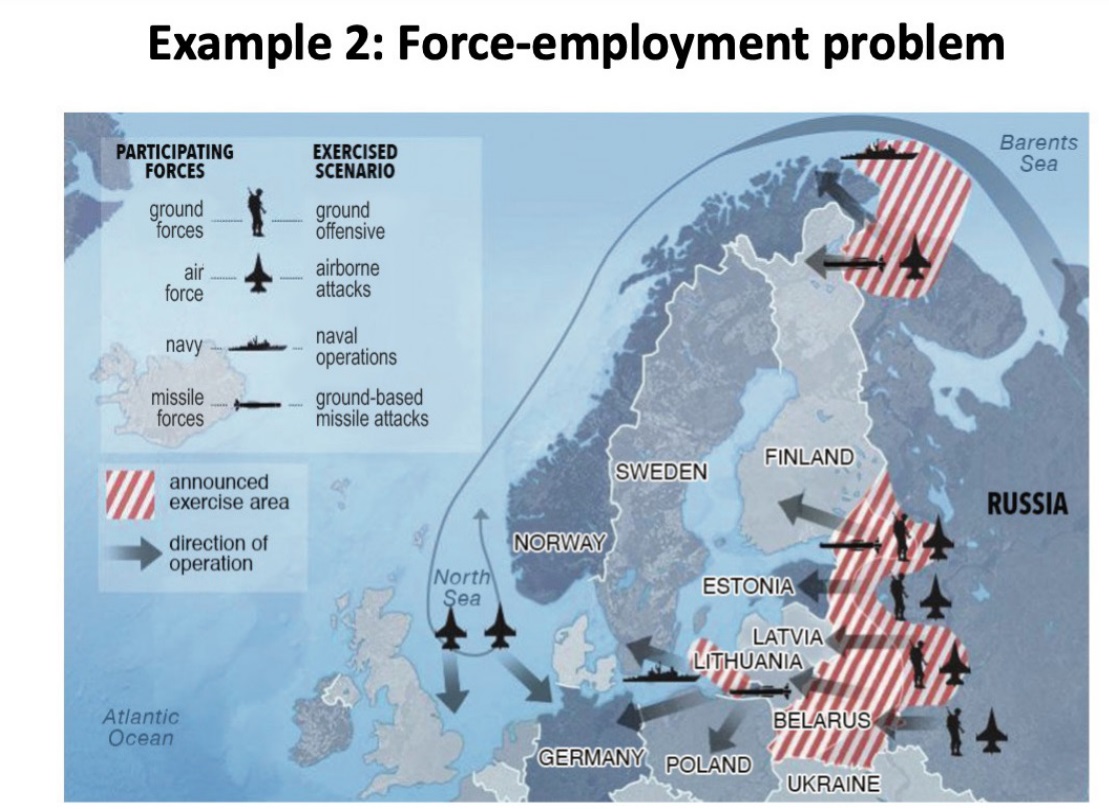

U.S. maritime alliances are grounded not only in strategic theory but also in geography and history. Seas were once understood as natural buffers that insulated states from threats. But once these seas became crowded with military and civilian vessels, these buffers became vulnerabilities that increased the number of potential flashpoints for conflict. NATO—one of the longest-lasting peacetime alliances in global military history—was sustained throughout the Cold War by a geopolitical reality in Europe that resembles today’s maritime domain. As demonstrated in the opening stages of World War II, a threat to the Netherlands or Austria quickly became a threat to Belgium, France, and Poland soon after. The maritime domain does not lend itself to being claimed and defended by individual nations like plots of land. Like Europe’s Cold War experience, it is impossible to contain conflict within the “bounds” of any one area in the seas. Moreover, because the high seas belong to no nation in particular, it is also a domain where strong states can readily coerce weaker ones, as highlighted by China’s actions in the South China Sea and East China Sea.

NATO was not only effective because it deterred military aggression; it also deterred political coercion and malign influence. As historian Timothy Sayle argues in his authoritative history of NATO, the alliance endured because it limited the Soviets’ ability to intimidate smaller European nations.2 With the horrors of WWII in recent memory, allies feared that weaker European states would rather capitulate to Soviet demands—as Finland did in the years after the war—rather than risk provoking another continental war. NATO was therefore a military organization that produced political effects and granted its members diplomatic resolve on top of collective security.

The Economic/Security Divergence and Other Challenges

Both of these functions performed by NATO in the Cold War are needed in today’s alliance architecture in the Indo-Pacific. The maritime nature of the Indo-Pacific theater facilitates the same potential for threat spillover as the central European plains did in the 20th Century. Additionally, China’s attempts to coerce other countries in the region necessitate a coalition that can resist both economic and military pressures. However, in today’s Indo-Pacific, a recognized need for alliances in the maritime domain does not necessarily translate into a perfectly unified front. Three recurring themes can be traced in the past and present of alliance management in the Indo-Pacific: (1) differences in priorities between the United States and its allies, (2) persistent concerns over free-riding, entrapment, and abandonment, and (3) historical, cultural, and geographic diversity as well as continuing animosity among U.S.-aligned actors.

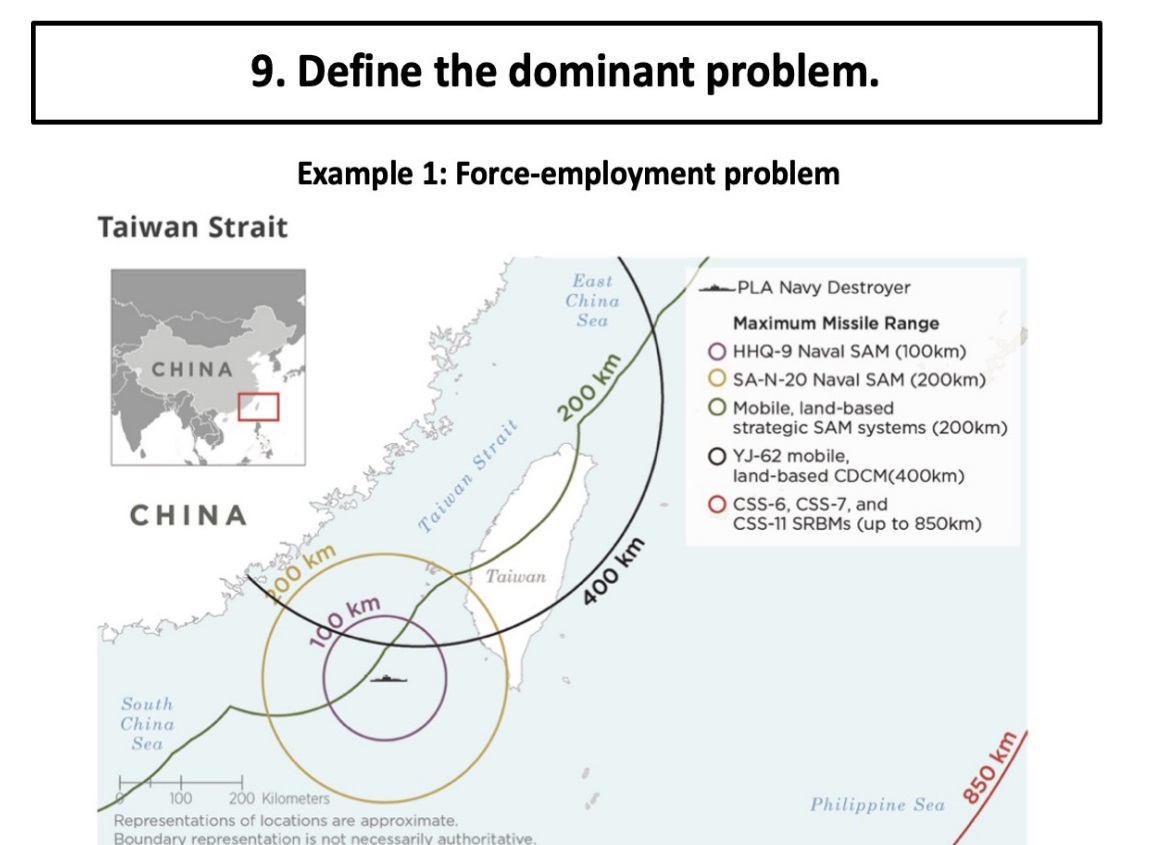

A decisive factor in any conflict between the United States and China or Russia is whether U.S. allies will offer military support. Especially when considering a potential conflict involving China—an economic juggernaut and a key trading partner for many U.S. allies—analysts have traditionally been skeptical on whether Washington can rely on its allies.3 This is where the Navy has a key role in both deterring conflict and shaping the battlefield for potential conflict.

A persistent but closing gap exists in the threat perceptions of the United States and our allies. American policymakers and observers often see China through a security lens and view its behaviors domestically and internationally as a threat to American interests and the international liberal order. U.S. allies and partners, however, have long seen China through an economic lens as a market and business partner. As Secretary Blinked acknowledged in a 2021 speech, fear being forced “into a “us or them” choice with China,” which might jeopardize key commercial activity.4 This perspective, however, is increasingly becoming more perilous as China leverages the economic dependency of other nations to coerce and co-opt. For example, China heavily sanctioned Australia in response to the Australian parliament taking action to rid its political system of malign Chinese influence.5

The Australian case also hints at a graver future where unchecked Chinese sea power will ultimately erase the economic benefits of smooth relations with China. In a different world with a preponderant and emboldened People’s Liberation Army Navy, Beijing could have not only struck Sino-Australian trade but all Australian trade by controlling shipping lanes to and from Australia. For instance, Chinese naval personnel could theoretically board and seize merchant vessels bound to Australia in a similar fashion to how U.S. and allied navies enforce sanctions against North Korea.

While this economic-security priorities gap has been closing recently, most notably demonstrated by the landmark Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) submarine technology sharing agreement, not all Indo-Pacific nations are equally prepared to draw the ire of China. The economic-security disconnect only aggravates American fears of being abandoned by allies during a conflict and allied fears of being entrapped in a conflict between the United States and China. From the perspective of multiple American administrations, allies have been too content to free-ride off the U.S.-enforced security order. Such sentiments result in calls to reduce American commitments to its security umbrella, which further degrades relations with allies. Through time, allies oscillate between fearing the United States will start a war that implicates its allies and fearing that the United States will leave its partners to its own defenses. This makes reassuring allies an ongoing balancing act.

The consequences of failing to reconcile allies’ economic priorities with security realities are most apparent in the conflict unfolding in Ukraine. Western Europe’s longtime reliance on Russian energy bred a general reluctance to take meaningful steps to deter Russian aggression toward former Soviet states, especially Ukraine. Changing a border by force for the first time since WWII through the 2014 annexation of Ukraine did little to change Europeans’ military calculus; incorporating Ukraine into the NATO security umbrella was still well beyond the imaginable.

Allied sea power might seem peripheral to the land invasion of Ukraine. However, the Black Sea plays a determinative role in Ukraine’s security; as much as 70% of Ukrainian trade travels by sea.6 Since 2014, NATO allies have shifted the bulk of the burden of patrolling the Black Sea to the United States.7 The failure to deter aggression in Ukraine has already led to a worldwide petroleum shortage, and it might also lead to other supply chain frustrations, especially in food and grain. The tragedy in Ukraine unveils the folly of prioritizing short-term economic concerns over long-term strategic problems.

Lastly, despite significant recent progress in forging an Indo-Pacific consensus, U.S. allies and partners differ widely in their contributions to collective security. A security mechanism that requires unanimity like NATO would be especially difficult with members that vary from tiny, authoritarian Singapore to the world’s most populous democracy, India. No common language or shared historical memory binds the region together, and the only common denominator among many Asian countries is the experience of war and occupation. For example, misgivings between Japan and South Korea dating back to WWII continue to stymie meaningful security cooperation and just a few years ago nearly derailed the intelligence-sharing agreement among the United States, South Korea, and Japan.8 Over the decades, the United States has painstakingly toiled to maintain its Indo-Pacific allies’ focus on the primary strategic issue—in this case, Chinese aggression—and prevent bilateral issues from flaring up and inhibiting slow but steady progress in strengthening cooperation. India’s recent reluctance to condemn Russia for its invasion of Ukraine is demonstrative of how difficult it is to keep a coalition on the same page despite the many other laudable accomplishments of the Quad.

Honor, Courage, and (Allied) Commitments

The leadership of the Navy and the other sea services recognize and are seizing the opportunity to contribute to U.S. alliances in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere. Because maritime security encompasses both the economic and military components of national power, the Navy is uniquely positioned to bridge the economic-security divergence between the United States and its allies. The sea services possess the institutional experience and policy tools to empower allies and partners and forge a tighter coalition to protect maritime security in the Indo-Pacific.

The AUKUS submarine deal is a prime example of one tool the sea services can leverage to enhance alliances: cutting-edge technology. AUKUS is only the most recent case of Naval technology being distributed to allies. The Navy’s hallmark weapons system, Aegis, is also utilized by Japan, Canada, Norway, South Korea, Spain, and Australia.[i] Such deals to utilize American technology facilitate long-term partnerships because these allies will need to cooperate with the United States in order to maintain, train, and upgrade these systems. They also improve the capabilities of a multi-national coalition. By operating with the same technology, an allied fleet can become much more interoperable, and therefore more lethal. The sea services should continue to share key technologies with partners, especially in areas where China is developing an asymmetric advantage, such as in cyber and space. The Quad’s recent initiative to provide a commercial satellite-based maritime domain awareness program to Indo-Pacific nations is one example of delivering technology to allies and partners.[ii]

Lastly, flexible operational models demonstrate the utility of combining capabilities of multiple allied navies. One model is the U.K.-led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), which comprises ships from Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Because this force is made up of 10 nations, compared to the 27 or 30 that make up the European Union or NATO respectively, it can deploy to a crisis much faster than these larger organizations. And the 10-nation JEF can still operate within NATO or EU auspices if requested.11 Moreover, navies in a multinational fleet that regularly conduct exercises and maritime security operations will become more familiar with their partners and have opportunities to work through cultural barriers and idiosyncrasies before scrambling in a large-scale crisis. Annual exercises such as the Pacific Vanguard (PACVAN, consisting of the United States, Japan, South Korea, and Australia)12 and Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC, consisting of dozens of navies from multiple regions, including Europe and South America)13 allow opportunities for Indo-Pacific navies—especially for mutually-suspicious nations such as Japan and South Korea—to develop operational familiarity with each other.

Warfighters? Diplomats? Both?

My fellow recently-commissioned officers might recall the fresh experience of Officer Candidate School and its emphasis on “delivering warfighters to the fleet”14 and be surprised by the diplomatic endeavors of the Sea Services. Junior officers need not be assigned to an attaché billet at an embassy to contribute to American diplomacy. A singular focus on warfighting simplifies our daily lives as Naval professionals, but it also overlooks half of the mission we are mandated to execute. Moreover, a greater focus on “maintaining security and deterrence” need not come at the expense of warfighting capability. Rather, improving our interoperability with allies in service of forging closer partnerships will only make the United States more formidable if conflict cannot be deterred. If the Navy leaves the upkeep of alliances to the State Department, we would then have to spend precious time during the opening stages of a crisis getting on the same page as our allies. This would ultimately dull our readiness, and therefore our lethality.

And for those outside the Department of Defense, the Navy’s prominent role in diplomacy might seem to reach beyond the Navy’s core purpose and affirm criticisms that U.S. foreign policy is over-militarized. Therefore, close coordination with other agencies, especially among the sea services and with the State Department, is vital to efforts in Naval diplomacy. The Navy does not duplicate the activities of the diplomatic corps, rather adds value to American foreign relations. Seizing the initiative to strengthen maritime partnerships enables the Navy to practice what the State Department and political leadership are constantly preaching.

The terms “whole-of-government” and “whole-of-society” are often used to describe the kind of efforts needed to overcome the China challenge. This should not only mean using a diverse set of our instruments of power to achieve our goals; it should mean using the tools at our disposal creatively and in ways that might not be obvious. Using American naval power to advance diplomatic objectives is one such way that the United States can strengthen its alliances and respond to the complex maritime threat posed by China. For a tricky task like building a broad, tight-knit maritime coalition, the United States needs all hands on deck.

Ensign Nicholas Romanow, U.S. Navy, is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. He is currently assigned to Fort Meade, Maryland, and working toward his qualification as a cryptologic warfare officer. He was previously an undergraduate fellow at the Clements Center for National Security.

The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy, or any other military or government agency.

References

1. Alfred Thayer Mahan, Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1660-1783), (Digireads.com Publishing, 2013), 80.

2. Timothy Andrews Sayle, Enduring Alliance, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 11.

3. Nicholas R. Nappi, “But Will They Fight China?” Proceedings 144, no. 5 (May 2018), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018/may/will-they-fight-china.

4. Antony Blinken, “Reaffirming and Reimagining America’s Alliances,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, March 25, 2021, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2550673/reaffirming-and-reimagining-americas-alliances/.

5. Natasha Kassam, “Great expectations: The unraveling of the Australia-China relationship,” The Brookings Institution, July 20, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/great-expectations-the-unraveling-of-the-australia-china-relationship/.

6. Brendan Murray, “Ukraine’s Ports Brace for More Economic Hardship in Russia Conflict,” Bloomberg, January 27, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-01-27/supply-chain-latest-ukraine-s-ports-brace-for-more-economic-hardship.

7. Alison Bath, US Navy and NATO presence in the Black Sea has fallen since Russia took part of Ukraine, figures show,” Stars and Stripes, January 28, 2022, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/europe/2022-01-28/sporadic-nato-patrols-in-black-sea-leaving-void-for-Russians-4443921.html.

8. Takua Matsuda and Jaehan Park, “Geopolitics Redux: Explaining The Japan-Korea Dispute And Its Implications For Great Power Competition,” War on the Rocks, November 7, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/geopolitics-redux-explaining-the-japan-korea-dispute-and-its-implications-for-great-power-competition/.

9. Lockeed Martin, Aegis Combat System, accessed November 30, 2021, https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/aegis-combat-system.html.

10. Zack Cooper and Gregory Polling, “The Quad Goes to Sea,” War on the Rocks, May 24, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/05/the-quad-goes-to-sea/.

11. Sean Monaghan, “The Joint Expeditionary Force: Toward a Stronger and More Capable European Defense?,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 12, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/joint-expeditionary-force-toward-stronger-and-more-capable-european-defense.

12. Petty Officer First Class Gregory Juday, “U.S., Allied Forces conduct Exercise Pacific Vanguard 2021 off Coast of Australia,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, July 9, 2021, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2689702/us-allied-forces-conduct-exercise-pacific-vanguard-2021-off-coast-of-australia/.

13. Commander, U.S. 3rd Fleet Public Affairs, “U.S. Navy Announces 28th RIMPAC Exercise,” U.S. Navy, May 31, 2022, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3048569/us-navy-announces-28th-rimpac-exercise/.

14. PO1 Luke J McCall, Delivering Warfighters to the Fleet, Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, September 29, 202, https://www.dvidshub.net/video/815735/delivering-warfighters-fleet.