By Ridge Alkonis

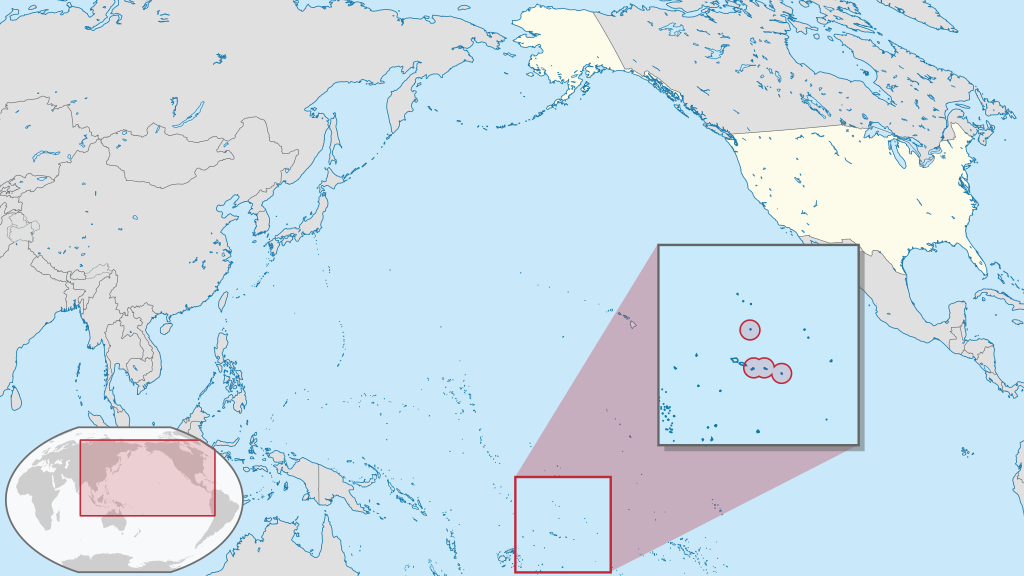

Regardless of prognostications of future conflict it is clear that the history of the 21st century will be written in the Indo-Pacific. Accordingly, as the United States steams into in an increasingly turbulent maritime security environment, it should not discount harvesting “easy wins” in the region. Compared to the marquee U.S. military installations at Diego Garcia, Yokosuka, or Guam, American Samoa is a U.S. territory that evokes images of idyllic island life rather than strategic competition. However, by considering American Samoa through the lens of strategic competition, a military installation manned by the U.S. Coast Guard is an easy step to demonstrate commitment in the region that makes imminent sense for several reasons. Due to the sheer distances involved in the Pacific — the closest Coast Guard installations are from Hawaii (2,260 nautical miles) and Guam (3,120 nautical miles) — current sustained operations in region are necessarily expeditionary.

Establishing a Coast Guard installation in American Samoa would lengthen the reach of the Coast Guard’s highly capable Sentinel class cutters, galvanizing partnerships throughout the Southern Pacific. With increasing concerns surrounding illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing (IUUF), the law enforcement presence and know-how of the U.S. Coast Guard will be a boon to safeguarding erosion of geographic and economic sovereignty of island nations in the Southern Pacific. This approach dovetails with the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy, which calls for “Build[ing] Connections Within and Beyond the Region.” Notably, the U.S. Coast Guard is one of the few government agencies called out by name in the strategy. One of the great contributions and strengths of the Coast Guard are the multitude of unique service and agency relationships and bi-lateral agreements it shares with international partners. . Expanding Coast Guard presence in the Southern Pacific has the potential to enhance dozens of bilateral and multi-lateral relationships for the United States while bolstering maritime security in the region.

Regional Consequences

The state of play in the region which necessitates U.S. Coast Guard presence in the South Pacific is best viewed through the prism of climate change and IUU fishing. U.S. stakeholders and defense watchers may express significant and well-founded concern with Chinese expansion in the region, as evidenced by the recent Solomon Islands security agreement, while regional leaders find themselves more concerned with immediate threats like climate change and IUU fishing.

IUU fishing is among the greatest threats to ocean health and is a significant cause of global overfishing. This contributes to the collapse or decline of fisheries that are critical to the economic growth, food systems, and ecosystems of numerous countries around the world. The deleterious effects of IUU fishing manifest around the world due to the reach of largely Chinese owned and operated, distance water fishing fleets (DWF). They engage in industrial scale commercial fishing operations, many times illegally, in the waters of other states. Wholesale, it is not an exaggeration to say that IUU fishing is a singular threat to both the economic and geographic sovereignty of nations around the world. Relatedly, the downstream effects of IUU fishing exacerbate the environmental and socioeconomic effects of climate change. These specific problems are aggravated in a remote region such as the South Pacific where maritime domain awareness — broadly defined as the knowledge and awareness of the maritime activities within a given states’ jurisdiction — is generally lower and enforcement mechanisms are weaker.

President Biden is considering expanding the Pacific Remote Islands Marine Monument (PRIMNM). A major concern of the initiative (besides that it harshly impedes indigenous fishers), is it may allow foreign illegal fishing to take stronger hold inside U.S. Exclusive Economic Zones. Western Pacific Fishery Management Council member McGrew Rice warns, “We need to consider that the Pacific Remote Islands monument is surrounded by more than 3,000 foreign vessels that fish in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean.”* If President Biden expands the PRIMNM, the region would require a significant increase in maritime security forces to ensure illegal fishing does not imperil U.S. resources and render the PRIMNM impotent.

Added pressure from illegal foreign fishing fleets would have devastating consequences to the local American Samoa economy. A capable patrol force to oversee the surrounding fisheries is necessary to protect against (largely Chinese) distance water fishing fleets, whose blue water fishing fleet numbers some 12,490 vessels, a number that dwarfs the number of fishing vessels flagged or charted by South Pacific nations. The South Pacific’s tuna fishery is already under significant pressure from unregulated fishing, with 1 in 5 fish being caught illegally. Chinese fishing vessels also provide auxiliary support to People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) forces in the South China Sea. An increase in Chinese distance water fleets and influence in the South Pacific creates the opportunity for similar tactics in and around the islands of the South Pacific. The specter of an Indo-Pacific conflict could see a proliferation of Chinese distance water fishing fleets throughout the South Pacific pose an asymmetric threat to U.S. forces.

Climate change poses a serious threat the South Pacific, with several countries in the region ranking in the most vulnerable in the world. In fact, the leaders of many Pacific nations cite climate change as their number one existential threat, vice a host of security-related, Sino-centric concerns Western audiences often project onto the region. In conjunction with rising sea levels, an increased number of extreme weather events threaten critical infrastructure and highlight the need for a quick response humanitarian and disaster relief capability in the region. For example, recent calamities caused significant damage to Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa, with estimates of the damage amounting to over 60 percent of GDP in some cases. A dedicated “quick reaction” disaster relief force would act as a safety net for the region, able to respond to both large scale calamities and smaller scale but critically urgent situations. For example, recently Kiribati’s Kiritimati atoll ran out of freshwater. The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Oliver Berry was the first on scene, using its reverse osmosis machine to create fresh water and pump it into tanks waiting on shore for the 5500 residents of Kiritimati atoll.

Given this state of play, it is clear that the U.S. Coast Guard is an ideal fit to address U.S. specific security and economic concerns that align with those of the region more broadly. Critically, permanently stationing Coast Guard cutters in American Samoa would skirt well-founded concerns of militarizing the Indo-Pacific. Compared to a U.S. Naval installation, a Coast Guard outpost would be perceived as more genuine and less bellicose given the unique contributions the service can make to the region.

The Sentinel Class Cutter

A significant body of work exists that extols the virtues of the Coast Guard’s Sentinel class cutters, praising the cutter’s multi-mission utility. The Sentinel class is a highly capable platform already operating in OCONUS locations like U.S. 5th fleet in Manama, Bahrain, Honolulu, HI, and the newly minted Coast Guard Patrol Forces Micronesia in Guam. Despite the acclaim for the platform, feedback from recent expeditionary patrols has been measured, with one operational commander noting, “We’ve been lucky because we’ve done really good operational planning, and we put a lot of attention on the success of this mission. But we’re exceeding the design and operational intent of what this asset was created to do.”

Operating in a surface action group (SAG) with larger seagoing buoy tenders, the Sentinel class cutter Joseph Gerczak recently completed “proof of concept” transits from Hawaii to Tahiti and American Samoa respectively, operating well outside its five-day, 2,500 nautical mile endurance limits. Ever “Semper Paratus,” the cutter reported utilizing after-market freezers and coolers on the ship’s weather decks to house enough provisions for the voyage. The cutter also had to meticulously monitor their fuel load to have enough fuel to complete missions in Tahitian and Samoan waters — made complicated by the fact that the turbo-charged marine diesel engines are meant to be run at high speeds which are not conducive to fuel conservation. This plucky resourcefulness underscores the risks that would be eliminated by placing cutters in American Samoa. Operating out of a central location would intensify the positive impact of having several capable assets able to saturate a given area.

Practicalities

Despite their lack of a flight deck, Sentinel class cutters are the top-choice for an expeditionary squadron, due to their shallow draft. Despite the range of larger Coast Guard cutters, their deeper draft makes some remote South Pacific locations inaccessible. Accessibility raises important questions about the practicality and logistics associated with several Sentinel class cutters operating out of Pago Pago Harbor. If the state of American Samoan critical infrastructure is any indication, then plans for a Coast Guard presence will require significant funds and creative planning. In 2019 the Army Corps of Engineers found the Lyndon B. Johnson tropical medical center to be in a state of failure, “due to age, environmental exposure, and lack of preventative maintenance. Extensive repair and/or replacement of facility sections is required to ensure compliance with hospital accreditation standards and to ensure the life, health, and safety of staff, patients, and visitors.”

Given this state of affairs and the limited budget of the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is unlikely to spearhead the service’s expansion into the region. The Coast Guard presence in Guam enjoys use of U.S. Navy built and owned facilities. Despite protestations about militarizing the region, a practical way forward could be utilizing U.S. Navy funds to stand up a small naval installation for primary use by the Coast Guard. Naval personnel, like a detachment of Seabees, as the Secretary of the Navy has suggested to assist with climate resilient infrastructure in the region, could use facilities on American Samoa as a central operating location.

The permutations of such a base are large, but in principle should include pier, maintenance, and shoreside facilities. Such a facility could pave the way for a long-heralded U.S. Coast Guard Forces Indo-Pacific, with cutters synchronizing operations out of Guam and American Samoa. Further, if the Navy adopts the Sentinel class cutter as a small surface combatant, an installation in American Samoa would increase interoperability between the sea services while carrying out missions on the low end of the competition spectrum. This model is attractive because it frees up larger capital U.S. Navy and Coast Guard assets for equally critical, but more technically demanding missions, such as freedom of navigation exercises, counter-narcotics, or responding to emergent crises such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Critically, following the results of a Trump administration era feasibility study, local government leaders support the stationing of U.S. Coast Guard assets in American Samoa given the need to both strengthen and diversify the economy while combating Chinese influence in the region. The U.S. Congresswoman from Samoa, Uifa’atali Amata affirmed, “We in American Samoa welcome talk in Washington of home porting a squadron of U.S. Coast Guard cutters in Pago Pago Harbor.”

The American Samoa economy relies heavily on tuna fishing. Fourteen percent of the American Samoa workforce comes from the tuna canning industry, an amount large enough to affect many facets of life on the island. Affordable energy, transportation, and retail all benefit from the presence of the lone tuna processing plant on American Samoa. A U.S. military presence of any form would not only transform maritime governance in the region, but galvanize and diversify economic growth on American Samoa.

Conclusion

It is clear there are manifold benefits of a U.S. Coast Guard presence in American Samoa, and the Sentinel class cutter is well suited for the role. The Coast Guard’s contributions to maritime governance, through both training and enforcement, should help stabilize a region lacking maritime domain awareness and enforcement mechanisms. The soft power of the U.S. Coast Guard presence in American Samoa will assuage fears about over-militarizing the Indo-Pacific region, yet, if a large-scale conflict were to materialize, ready-made infrastructure in American Samoa could prove crucial for maintaining U.S. and allied sea lines of communication. One thing is for certain, with the eyes of the world on the Indo-Pacific, solutions for keeping strategic competition within reasonable parameters should not be overlooked.

Sentinel class cutters operating out of Pago Pago harbor represent a powerful, permanent deterrent to IUU fishing in the vast stretches of the Southern Pacific Ocean and would be optimally postured for acting as a timely humanitarian and disaster relief force. Despite some practical details surrounding the base itself, such a presence would represent a transformational shift in maritime governance in the region, expanded bilateral relations with Pacific nations, and an economic boon for American Samoa.

LT Ridge H. Alkonis is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer currently serving as the Weapons Officer in USS Benfold (DDG 65) stationed in Yokosuka, Japan. Originally from Claremont, California, he is a 2012 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, with a B.S. in Oceanography and the Naval Postgraduate School where he earned a M.S. in Acoustics Engineering.

*This quote has been updated following a clarification from the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council.

References

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/27/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-national-security-memorandum-to-combat-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-and-associated-labor-abuses/

- https://www.marinelink.com/news/uscg-report-small-cutters-prove-patrol-a-497335

- https://chuckhillscgblog.net/2022/02/15/a-new-coast-guard-base-in-the-western-pacific/

- https://www.talanei.com/2022/03/09/uifaatali-reiterates-call-to-base-uscg-cutters-in-pago-harbor/#disqus_thread

Featured Image: The Coast Guard Cutter Forrest Rednour arrives in San Pedro, California, Aug. 11, 2018. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class DaVonte’ Marrow.)