This article is a part of The Hunt for Strategic September, a week of analysis on the relevance of strategic guidance to today’s maritime strategy(ies). As part of the week we are also re-examining “Sacred Cows” – fundamental concepts that underpin the current approach to maritime security.

The effect of the ongoing budget crisis on the U.S. military is similar to the effect of drought on a farm. Farmers are sometimes forced to slaughter some animals during a drought in order to ensure the survival of a herd. The U.S. military also now appears poised to cut some pieces of weapon hardware in order for bulk of service programs to survive this particular period of fiscal shortages. In the case of the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet, this “culling of the herd” could include cuts in both current platforms and new construction. Rather than retire ships with useful remaining service life, or cut planned new construction, the Navy should bring back a manning concept with its roots in the age of sail.

Adoption of a nucleus crew system for those ships not deployed, or training to do so would ensure the retention of useful warships, maximize manning for deployed units, and save some money in personnel costs. Great Britain’s Royal Navy (RN) faced a similar demand by civilian authorities in the first decade of the 20th century to both cut its budget, and maintain its superiority in fleet strength over potential adversaries. The RN adopted the nucleus crew system and successfully preserved a number of middle-aged ships that saw useful service in the First World War. While it is never an ideal situation to have a warship manned at anything less than its authorized crew complement, the current budget crisis demands extraordinary action. Adoption of nucleus crews in some ships may allow the Navy a period of pause to develop more long-term solutions to extended periods of fiscal drought.

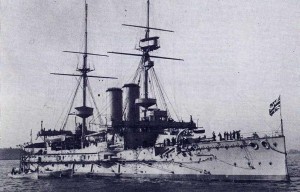

It is first useful to examine the British nucleus crew program. The RN experiment in nucleus crews was begun during the tenure of Admiral Sir John Fisher as the First Sea Lord (rough equivalent of the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations) from 1904-1910. An iconoclast who was not afraid to break established rules and traditions, Fisher was selected by the civilian First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Selborne, to both reduce naval budgets and reform and prepare the RN for modern warfare. Part of Fisher’s program involved accelerating the building of modern “Dreadnought-style” battleships and battle cruisers, modern submarines, and early experiments with naval aviation. His initial change to the existing fleet was to cut over 150 aging or ineffective warships from active service. While draconian in effect, these cuts allowed Fisher to preserve another cohort of “middle-aged” battleships, cruisers and destroyers that might also have been retired to meet budget goals. His ingenious program to retain these ships was to reduce their crew complements to a smaller “nucleus crew” of 3/5 normal crew complement. These reduced crew cohorts would be capable of maintaining the ships and taking them to sea for short periods of training. The nucleus crew consisted primarily of officers and technical experts who could care for the ship over periods of inactivity. In case of crisis, the nucleus crew ships could be brought to operational readiness through the addition of relatively untrained crew members such as stokers (necessary in large number for the coal-fired ships of the day), additional gunners and deck seamen.

Fisher was very successful and far exceeded his political masters’ expectations. He was able to provide sufficient manning to fill new construction units and created accountable reserve formations of warships that could be activated through a precise system for war. The RN’s budget for 1905 was 3.5 million pounds less than 1904 while still supporting a full program of new constructions. RN budget estimates continued to fall from 1905-1907 and did not return to 1904 levels until 1909 when the Admiralty requested eight new battleships in response to the growing German battleship program. When the First World War began in August 1914, the RN was able to return many nucleus crew vessels to full operational capability for patrol, convoy escort, and shore bombardment duties. The march of naval technology however had made many of the nucleus crew ships even more antiquated then they were in 1905 when the entered the program. Three aging armored cruisers recommissioned for patrol duties in the North Sea were sunk in the space of two hours by a modern German submarine with the loss of over 1400 lives. Two more elderly cruisers were destroyed with all hands (1500 personnel) off the coast of Chile later that year fighting the crack gunnery cruisers of the German Navy. Five former nucleus crew battleships were later lost trying to force the Dardanelles strait in Winston Churchill’s abortive 1915 campaign to knock Ottoman Turkey out of the war. While Fisher’s program preserved ships for reactivation, it did not provide for their modernization against new threats. Overall though, the Royal Navy viewed the program as successful in providing needed force structure for fighting a global war.

The U.S. Navy could slay one of its own “sacred cows” by adopting a modified nucleus crew system for the manning of surface combatants and amphibious ships not deployed nor in the training cycle to do so. This would involve significant changes in the manning programs of surface ships but the “payoff” would be similar to the British results a century ago in avoiding cuts in modern force structure and the preservation of current building programs. There are however a number of lessons learned from the RN experience that could be applied to improve its 21st-century U.S. application. First, rather than preserve aging units that cannot be modernized to keep pace with naval warfare developments, the U.S. should apply the nucleus crew to all ships home-ported in the continental United States (CONUS). Those ships permanently forward-deployed with the 5th, 6th, and 7th fleets would not be included in the nucleus crew program. Older ships like the Perry-class frigates, the Avenger-class mine countermeasures ships and the Cyclone-class patrol coastals would not be subject to the nucleus crew program, but cannot be cut from the active fleet as quickly as Admiral Fisher achieved his reductions. They would be retired as more littoral combat ships (LCS) are commissioned to replace them. Cruisers, destroyers, and amphibious warfare ships would regularly pass through a nucleus-crew phase in their normal deployment cycle rather then be reduced to a reserve status.

A typical ship would return from an operational deployment and be programmed by its Immediate Superior in Chain of Command (ISIC) and Naval Personnel Command to reduce its complement to 60% of nominal manning. The ship would be required to keep a viable inport watch organization and be capable of getting underway for short periods to avoid destructive weather or in response to other emergencies. The ship would retain a basic self-defense capability to include close-in weapons systems and small arms. It would be required to get underway monthly for one-day periods and quarterly for three-day periods to demonstrate equipment operation and nucleus crew skills. The experience of the Military Sealift Command (MSC) in manning ships, particularly the engineering and deck departments with minimal personnel may be useful in developing similar watch organizations for nucleus crew ships. This program of minimal underway training would continue until the ship entered a major shipyard availability or approached the next deployment training cycle.

If preparing to enter the shipyard for an extended period, the crew complement would be further reduced to 10% of overall manning. The shipyard authority would assume complete responsibility for the safety, security, maintenance, and upgrades to the ship in a formal turnover upon commencement of the availability. The shipyard team might also be organized and staffed based on MSC experience and rotate as required to manage ships in the yards. The remainder of the crew would be sent to schools and training commands for the duration of the yard period or augment deployed units with personnel shortages. The nucleus crew would return to the ship at the conclusion of the work and after a turnover period and completion of shakedown, resume full responsibility. The ship would remain in its nucleus crew status until it again prepared to conduct pre-deployment training. Additional crew members would be assigned to again swell the ship’s complement to full manning and return any equipment in layup maintenance to full capability. The ship would conduct it’s training cycle and deploy as scheduled. ISIC’s (destroyer squadrons, carrier and expeditionary strike groups) would closely monitor the transitions of nucleus crew ships from reduced to full manning and back to nucleus crew status.

The key to making this program work is the precise management of the personnel assigned to nucleus crew ships. The Navy would also need to ensure that the Department of Defense and Congress fully understand the nucleus crew policy and the limitations it will place on the ability of the Navy to rapidly deploy large formations of ships. British Admiralty officials spent a great deal of time answering questions in Parliament from 1905-1914 on the nucleus crew program. The historical record would indicate they understood the limitations the RN was imposing on a large part of its force to meet fiscal demands. Congress and Department of Defense would likely require a similar level of confidence in order to support the concept. While the program preserves important modern naval force structure, it limits the freedom of action decision-makers had in the past in using the Navy to react to crisis situations. A full force could be made available for a major war or engagement on par with the Iraq wars of 1991 and 2003, but with regard to operations of less scope and shorter length such as the 2010 Odyssey Dawn campaign against the Libyan government of Muammar Gaddafi, only those forces already deployed in theater would be available. The U.S. Navy budget savings would also be less than that achieved by the British in the early 20th century. Unlike the RN, who could operationally afford to keep their nucleus crew ships in port for long periods, the U.S. would need to re-man and deploy them on a regular basis. The end result could be much larger deployed U.S. formations in the Western Pacific, Mediterranean, and Arabian Seas than those in home waters, thus obviating the need for many traditional deployment cycles.

Adoption of the nucleus crew concept for CONUS-based combatants and amphibious warfare vessels would protect valuable force structure from budget cuts, provide additional flexibility in ensuring deployed ships are fully manned and afford some cost savings in personnel. Disadvantages include less flexibility in responding to crisis operations, a less cohesive training plan for nucleus crew ships since 40% of the crew is absent for a large part of the deployment cycle, and less ability to use nucleus crew ships in home waters. The one overriding argument for this plan however is that is preserves surface fleet force structure, albeit in reduced capacity rather than losing it wholesale to budget cuts. Quantity has a quality all its own, and in order to effectively police the “global common spaces”, the U.S. Navy must preserve the force structure necessary to achieve sea control when and where required by national command authority. The Navy can recruit and train new sailors with reasonable speed and efficiency. Once ships however are “mothballed” or scrapped, it may take a decade or more for replacement units to reach the fleet. Adoption of the nucleus crew concept by the U.S. Navy would ensure retention of valuable surface units in a continuing period of fiscal austerity.

For more on the nucleus crew concept, see Lazarus’ post at Information Dissemination.

Sea Control- Doyle Hodges Interview (Download)

Sea Control- Doyle Hodges Interview (Download)