The following article is part of our cross-posting partnership with Information Dissemination’s Jon Solomon. It is republished here with the author’s permission. You can read it in its original form here.

By Jon Solomon

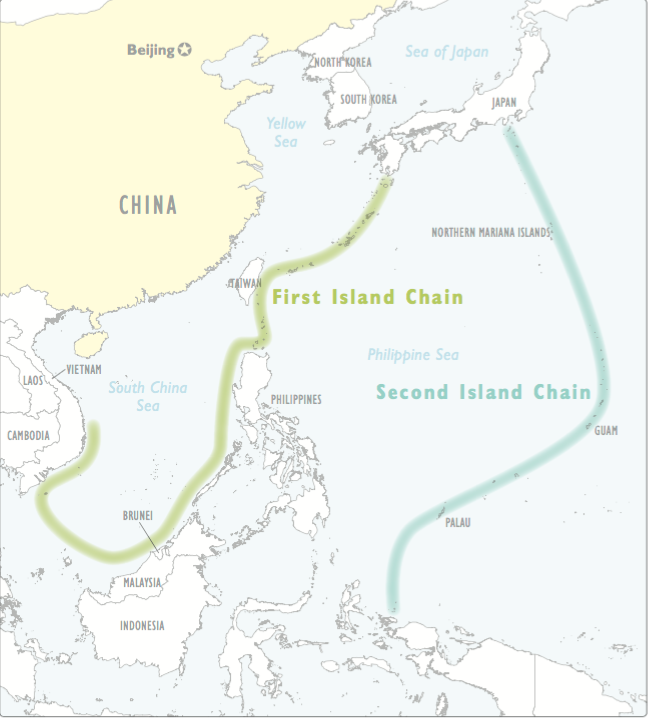

My recent post on how to counter Chinese anti-shipping capabilities between the First and Second Island Chains was heavily influenced by CAPT William Toti’s seminal article in last June’s Naval Institute Proceedings on the need to tackle anti-submarine warfare from a theater-wide, threat-tailored, combined arms campaign construct. If you haven’t read his article (which is outside the paywall), do so. It is a foundational work.

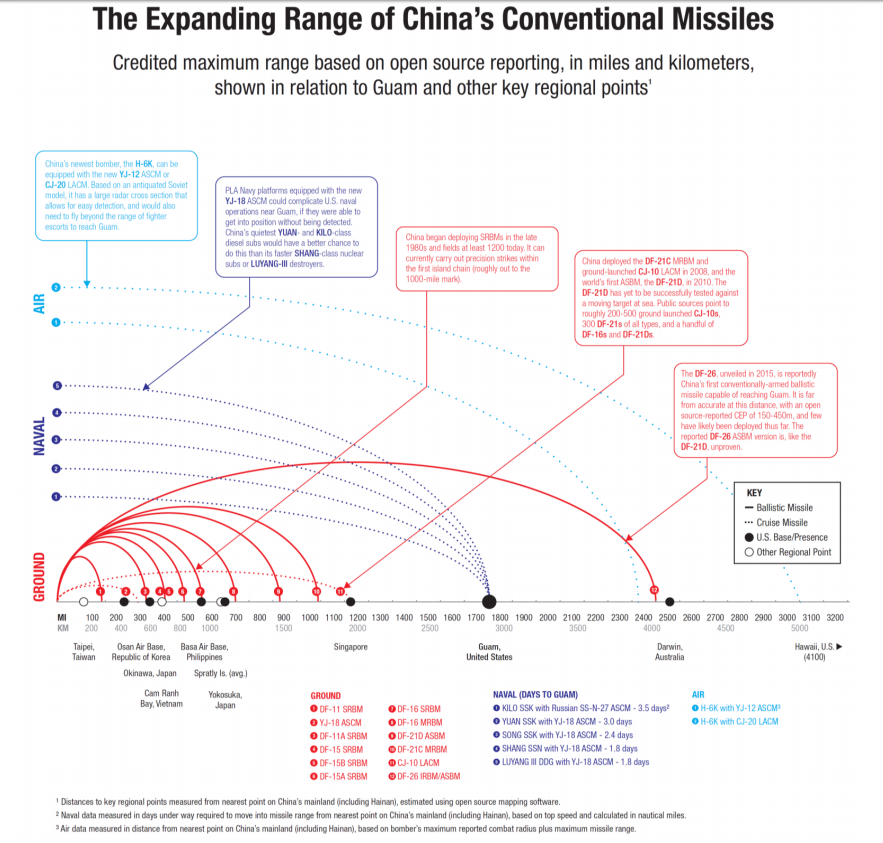

Toti observes that the dramatic sensor advantages that allowed the U.S. Navy to thoroughly dominate Soviet submarines throughout much of the Cold War no longer hold. Our ability to detect and attack an approaching adversary submarine before it can shoot first is uncertain at best. Yet, as Toti points out, “real ASW is not about detecting the submarine, it’s not about killing the submarine, it’s about defeating the submarine.”[i] The ability to win a close-in “knife fight” against a submarine, while important, represents just one of many opportunities to prevent the submarine from executing an effective attack. The submarine in wartime must, after all, have a safe haven in port for resupply, must break out of port, must transit through marginal seas or the open ocean to its patrol station, must be cued into patrol stations or intercept positions from which it would have the greatest opportunity for encountering prey, must detect and correctly classify a target (or receive targeting-quality cues from external surveillance and reconnaissance assets), must approach the target to weapons release range, and must land a blow with its weapon salvo. Most conceivable adversaries of the U.S. have the added geographical challenge of pushing their submarines through chokepoints such as straits in order to access the open ocean or return to port from patrol. Toti observes that there are exploitable vulnerabilities in each of these steps that can deny the submarine a chance to attack effectively and perhaps even lead to the submarine’s own destruction. Toti also notes that if a potential adversary’s leaders became convinced that the U.S. would be able to defang any submarine offensive, they might opt not to employ their submarines—or go to war—in the first place.

In rereading Toti’s article the other week, it occurred to me that there are remarkable parallels between what he suggests could be done to wage a wartime theater anti-submarine campaign and what could be done to wage a campaign to defeat an adversary’s wartime use of theater-range conventionally-armed ballistic and cruise missiles. His recounting of the Navy’s “full-spectrum ASW” doctrine provides an excellent model for tying together a combined arms “full-spectrum anti-theater missile campaign” concept along the lines of what Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work dubbed “raid breaker” earlier this year.[ii]

Just as ASW doesn’t depend entirely on destroying the submarine, theater missile defense doesn’t depend entirely on destroying the inbound theater missile. With this in mind, we see that each of Toti’s “ten threads of full-spectrum ASW” has an anti-theater missile analogue:

| Full Spectrum ASW | Full Spectrum Anti-Theater Missile Warfare |

| Defeat submarines in port | Suppress missile-armed mobile platforms’ basing and logistical support infrastructure |

| Defeat the submarines’ shore-based command and control capability | Defeat the systems-of-systems that missile-armed mobile platforms rely upon to attack effectively |

| Defeat submarines near port, in denied areas | Defeat missile-armed mobile platforms as they break out of bases/garrisons towards their firing positions |

| Defeat submarines in choke points | Defeat missile-armed air and naval platforms in choke points |

| Defeat submarines in open ocean | Defeat missile-armed mobile platforms in their patrol or firing areas |

| Draw enemy submarines into ASW “kill boxes,” to a time and place of our choosing | Induce missile-armed mobile platforms to fire at false targets and perhaps expose themselves to attack |

| Mask our forces from submarine detection or classification | Mask our forces from the adversary’s local reconnaissance and targeting efforts |

| Defeat the submarine in close battle | Defeat missile-armed air and naval platforms in close battle |

| Defeat the incoming torpedo | Defeat the inbound missile |

| Create conditions where an adversary chooses not to employ submarines | Create conditions where an adversary chooses not to employ theater missiles |

Let’s go through the anti-theater missile “threads” in turn. As we proceed, note that I implicitly discard the option of engaging in war-opening preemptive attacks against an adversary’s theater missile forces. With the exception of certain types of electronic or cyber operations, I work under the assumption that most of the below types of attacks would only be authorized by a U.S. President after a war has already started.

Suppress Missile-Armed Mobile Platforms’ Basing and Logistical Support Infrastructure

Theater missile-firing platforms include aircraft, submarines, naval surface combatants, and Transporter Erector Launchers (TEL). All of these platforms require logistical support including rearmament, refueling (with the exception of SSNs, of course), replenishment of stores, corrective maintenance, and damage repair. In war, the bases in which they normally reside, receive servicing, and operate from can be attacked (assuming authorization from political leadership, which I’ll discuss in more detail below).

Nevertheless, not all of these platforms need to always return to a permanently-fixed base for all forms of servicing. For example, many missile-firing platforms can operate from and be serviced to some extent in austere locations such as seaports, airports, “satellite” airbases or ad hoc airstrips, or relocatable logistical depots. Some missile-firing platforms can have fuel, stores, repair parts, and even certain types of munitions brought to them in the field: replenishment ships can resupply surface combatants and sometimes submarines at sea, trucks or transport aircraft can resupply strike aircraft at austere airbases/airstrips, and trucks can resupply TEL units. All of these means for logistical support in the “field” can be directly attacked given sufficient intelligence, surveillance, or reconnaissance to know when and where to strike. Moreover, the depots and other fixed infrastructure that logistics forces inevitably pull from can also be identified and attacked. There’s an important caveat, though: the heavy wartime demands on U.S. strike-capable platforms and the finite size of their guided munitions inventories suggests that (politically authorized) targeting lists would have to be prioritized based on a particular logistical asset’s or site’s importance in the adversary’s combat logistics chain, plus the operational and tactical difficulties/risks in attacking that target.

This leads to a key point: an intelligent adversary could employ many forms of deception and concealment to heavily complicate U.S. and allied targeting efforts against a logistical asset/site or the missile-armed platforms it was servicing. Nevertheless, many forms of concealment would require that the adversary reduce its missile forces’ operational tempos somewhat in order to reduce the risk of detection, classification, and attack. This might relieve some pressure on friendly air and missile defenses by suppressing the frequency and sizes of missile raids on the margins; this can have a significant effect on a given defense’s probability of annihilating a raid. In turn, this suppression might provide friendly forces increased temporary localized margins of operational freedom in a theater—not to mention possibly alleviate some margin of pressure on allied populations and their governments (and by extension on U.S political leaders).

Attacking an adversary’s theater missile forces’ bases along with much of their supporting logistical infrastructure would require strikes against the adversary’s home soil. U.S. political leaders would undoubtedly weigh the escalatory risks of such strikes against the consequences of allowing the adversary to enjoy operational sanctuary for its missile forces. Some critics suggest these escalatory risks would—and should—bar the U.S. from ever attacking a nuclear-armed adversary’s soil. Such critiques however do not recognize the high probability that if the adversary valued certain political objectives highly enough to opt for major war, those objectives would force him to commit the escalatory precedent of conventionally striking a treaty ally’s territory—and perhaps also sovereign U.S. territories—first. This is of immense strategic significance. For one thing, an adversary’s conventional first strike against U.S. or allied territories would almost certainly ignite the popular passions of the victims’ citizens. The pressure on a U.S. President to retaliate in scope if not in kind would be intense. For another, the adversary’s first strike would allow the U.S. and its ally to invoke unassailable legal as well as moral justification for retaliation. These factors would not offset the nuclear risks of non-nuclear retaliation, but it should be noted that there is an enormous difference between selectively striking conventional forces that might carry theater nuclear weapons and striking distinct nuclear forces. In many cases, the bases and logistical infrastructure supporting conventional forces are distinct from those used by nuclear forces. For example, China’s theater nuclear forces (in the form of its DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile force) are distinct (and often geographically segregated) from its conventionally-armed short-range ballistic missile and long-range cruise missile forces.

None of this is meant to minimize questions of escalation risk facing a U.S. President, but they most certainly do not present a “checkmating” barrier that prevents operations to deny the adversary’s theater missile forces sanctuary. It bears observing that potential adversaries wouldn’t be investing heavily in integrated territorial air defenses, base hardening, and deception and concealment technologies to protect their conventional theater missile forces if they didn’t accept the reality that those forces might be attacked in war.[iii]

Defeat the Systems-of-Systems that Missile-Armed Mobile Platforms Rely Upon to Attack Effectively

I’ve previously written about these kinds of operations at length. Suffice to say, an adversary must be able to either provide correct targeting-quality tactical pictures to its firing units or be able to cue those “shooters” into positions from which they can use their own sensors to build local targeting pictures. The U.S. and its allies can use deception and concealment to prevent the adversary from being able to effectively attack protected mobile forces. This can also be done to some extent for fixed bases and military or civil infrastructure, as deception and concealment can be used to make unimportant sites look important and vice versa. Deception and concealment might additionally be used to induce the adversary to waste precious weapons (and expose firing platforms) in attacks against false or low-value targets. The U.S. might additionally attack the adversary’s surveillance and reconnaissance assets, precision navigation and time systems that allow the construction of an accurate situational picture, command and control sites where firing decisions are made, and data relay pathways that form the “backbone” of the entire apparatus. These attacks can be physical, but in many cases it might be more effective as well as carry less escalation risk to use electronic or (as technically plausible) cyber attacks. Nor do these attacks need to have permanent effects (though that would certainly be the ideal), as friendly forces could greatly capitalize on even temporary localized degradation of the adversary’s surveillance-reconnaissance-targeting infrastructure.

This “thread” would not prevent an adversary from using its conventionally-armed theater missiles in terror bombardment campaign against an American ally’s cities. Even so, history suggests such a campaign would be far more likely to further ignite the ally’s popular passions and deepen its resolve to prevail—and retaliate—than it would to coerce the ally into submission. In other words, it would be a strategically self-defeating move by the adversary.

Defeat Missile-Armed Mobile Platforms as They Break out of Bases/Garrisons Towards Their Firing Positions

As Toti observes, this “thread” would largely occur within “denied” areas such as the adversary’s own soil, any friendly or neutral territories occupied by the adversary’s forces, the airspace above or adjacent to these territories, or the waterspace adjoining these territories. This would accordingly complicate offensive anti-air, anti-submarine, anti-surface combatant, and anti-TEL operations. Nevertheless, friendly submarines could lurk offshore to intercept the adversary’s submarines and surface combatants. Offensive sweeps by theater-range fighters might be used when and where feasible to attack the adversary’s outbound aircraft. Standoff strike aircraft cued by penetrating scouts might be used to attack the adversary’s surface combatants. If adequate air superiority is present, maritime patrol aircraft might be used to search for and attack adversary submarines. Special forces might be used to cue attacks using penetrating aircraft or long-range guided munitions against TELs (though if the First Gulf War is any indication, probably without a great deal of success). Destroying missile-firing platforms would of course be ideal, but the real goal of this “thread” would be to make breakout more time-consuming and resource-intensive than it might otherwise be for the adversary. This might result in further suppression of his operational tempo. It might also prevent him from seizing or maintaining the operational initiative.

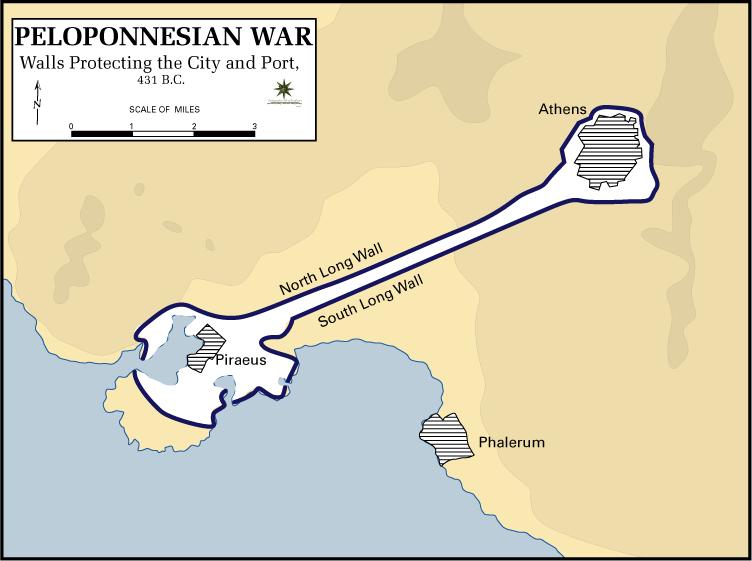

Defeat Missile-Armed Air and Naval Platforms in Choke Points

I covered this with respect to aircraft and submarines last week; the threats facing an adversary’s surface combatants would be even steeper. This forms part of the argument for deploying land-based anti-ship missiles alongside straits. Land-based surveillance assets bordering a strait can also cue anti-ship strikes by friendly aircraft operating from more distant bases. Similarly, these surveillance assets can provide other friendly forces with tactically-actionable indications and warning of a strike aircraft raid transiting through a choke point towards its targets or back to its airbases. Lastly, defensive minefields could be laid as geographically practical to complicate transits by the adversary’s surface combatants or submarines.

Defeat Missile-Armed Mobile Platforms in Their Patrol or Firing Areas

I also covered this with respect to aircraft and submarines last week. In the absence of persistent tactical air cover, an adversary’s surface combatants would not be able to hold out for long against U.S or allied anti-ship onslaughts.

TELs present the hardest target to engage in the adversary’s firing areas, bar none. They not only can hide within the broad expanse (and defense-in-depth) of the adversary’s territory, but can also blend into their surroundings on par with the quietest submarines at sea. They can shift quickly and frequently between prepared firing positions, or can hunker down heavily camouflaged for protracted periods. There is no existing or technically-plausible weapon system that could offer a high kill probability against TEL units that were smartly employing deception and concealment. Nor is there an existing or technically-plausible strike aircraft that could persistently perform TEL hunts deep within a capable adversary’s airspace unless the adversary’s territorial air defenses had been comprehensively rolled back. This does not mean that TEL hunting, if the tactical environment allows it, would be fruitless. The situation-dependent use of U.S. aircraft to hunt TELs using cheap weapons with low kill probabilities would still put TEL units on the defensive, which in turn might contribute to suppressing TEL firing rates and salvo sizes.

The most effective means of defeating ground-launched missile forces is to physically occupy the territory they are operating within. This is a principle that has been proven time and time again, from the allies’ Second World War efforts to defeat the German V-1 and V-2 bombardment campaign, to the Israelis’ efforts to break up Hezbollah and Hamas rocket bombardment campaigns over the past decade. It’s also the most costly in treasure and blood, as it requires the use of sizable ground forces. This is plausible and probably necessary if the adversary is operating TELs on the overrun soil of a U.S. ally; liberation of the ally’s territory would normally be a U.S. war objective in any case. It may also be plausible, albeit possibly far more costly, if a relatively small adversary country is operating TELs on its own soil. It is not plausible at all, whether militarily or politically, against TELs operated on the soil of a regional or great power. However, if a regional or great power is operating TELs relatively close to its border or coastal areas, and especially if those areas are somewhat geographically isolated, it might be plausible to dispatch special forces on brief raids aimed at destroying them directly, flushing them for attack by other friendly forces, or temporarily suppressing them by inducing them to go into hiding. Expeditionary forces might also be used to raid a regional power’s TELs in these kinds of areas; this would not be possible politically or militarily against a great power.

Induce Missile-Armed Mobile Platforms to Fire at False Targets and Perhaps Expose Themselves to Attack

I’ve written about this one extensively in the past as well. Every theater missile wasted is one less in the adversary’s finite inventory, with concomitant impacts on his campaign plans. This is especially true if a wasted missile cannot be readily replaced off the production line during wartime.

Similarly, an adversary platform or grouping that is seduced into attacking false targets will be incapable of attacking valid targets elsewhere at the same time. U.S. and allied forces can obviously exploit this operationally. At maximum, a submarine, surface combatant, or aircraft that shoots a theater missile gives away its general presence and sometimes even its approximate position. False targets might thus be used to set up reactive intercepts against the attackers, or perhaps even to lure them into prepared ambushes. It isn’t a stretch to imagine the kinds of enduring (and exploitable) psychological effects that might be imposed upon previously-overconfident adversary crews that wasted ordnance against decoys—or managed to survive an ambush.

Mask our Forces From the Adversary’s Local Reconnaissance and Targeting Efforts

This is another “thread” I’ve covered previously elsewhere. It is just as crucial to the use of false target tactics in the previous “thread” as it is to defending actual U.S. and allied forces from attack. The adversary must not be allowed to properly classify, let alone detect if at all practical, actual U.S. and allied forces until it is too late to matter. Toti hits the nail on the head in his piece when he notes “…it is about increasing the fog of war by making the real targets look like anything but a real target” and that it “must be a continuous process.”[iv]

Defeat Missile-Armed Air and Naval Platforms in Close Battle

This is self-explanatory: destroy them or induce them to retreat before they can shoot at friendly forces. This demands either long-range weaponry that can be fired from the “inner zone” against the adversary’s inbound missile-armed platforms or the placement of persistent outer layer defenses in the adversary’s path. The latter is almost always preferable as the adversary can easily field strike missiles that outrange any weapon the defender might fire from the inner zone.

As its title makes clear, this “thread” is not applicable to TELs.

Defeat the Inbound Missile

This is also self-explanatory. Missile defense sensors, kinetic weapons, and electronic warfare systems all factor here. So does damage recoverability (e.g. use of redundant systems, rapid repair of damaged runways, hardening of a base’s critical infrastructure, shipboard damage control, etc). No single measure offers a panacea: some combination of active and passive measures is necessary to maximize defensive effectiveness.

A subtle variation of this “thread” involves the dispersal of forces not just to enhance their survivability, but also to force the adversary into an inventory management dilemma. The adversary could concentrate strikes over a specific period of time against a small number of force dispersal sites in order to overwhelm the missile defense systems protecting those sites, but that would leave the U.S. and allied forces positioned in other dispersal sites free to operate. The adversary could alternatively strike the maximum number of dispersal sites possible within a specific time period, but that would result in relatively few missiles attacking any single site—and thereby greatly simplify the jobs of each site’s missile defense systems. Also recall that theater missiles are not easily produced, especially in war. This means every missile fired would reduce the number available to the adversary for the duration of the conflict. As such, the adversary would probably have some threshold limit to the number of missiles he’d be willing to use in a concentrated or “spread” attack. U.S. and allied forces could adapt to capitalize on whichever attack type the adversary selected, and by doing so defeat the adversary’s theater missiles at the operational level of war.

Create Conditions Where an Adversary Chooses not to Employ Theater Missiles

Full-spectrum anti-theater missile warfare signifies denying the adversary conventional escalation dominance in a crisis or war. The cumulative effect of convincing an opportunistic potential adversary that each of its “threads” are combat-credible—and that U.S. political leaders would be willing to deny the potential adversary’s forces operational sanctuary on their own soil if the adversary struck first—will generally be successful conventional deterrence.

The ideal state of deterrence would obviously be prevention of war outright, and Cold War-era theories regarding how this can be achieved between two competing nuclear-armed powers remain applicable. But even if a conventional war did erupt, the credibility of full-spectrum anti-theater missile warfare might help induce an adversary with modest political objectives to keep the conflict limited to a brief localized clash along a land border or at sea involving only the shortest-range missiles in both sides’ inventories. While tragic and hardly desirable, it would still be vastly preferable to a ruinous general war.

Jon Solomon is a Senior Systems and Technology Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. in Alexandria, VA. He can be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.

Endnotes

[i] CAPT William J. Toti, USN (Retired). “The Hunt for Full-Spectrum ASW.” Naval Institute Proceedings 140, No. 6, June 2014, 39.

[ii] I define “theater missile” to include short and medium range ballistic and cruise missiles that can strike targets on land or at sea.

[iii] This point is made abundantly clear in Elbridge Colby. “Don’t Sweat Air Sea Battle.” The National Interest online, 13 July 2013, accessed 5/24/15, http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/dont-sweat-airsea-battle-8804?page=show

[iv] Toti, 43.

Featured Image: ARABIAN GULF (March 20, 2011) Mineman Seaman Charles Bryan watches for contacts on the SPA 256 radar while on watch in the Combat Directive Center aboard the mine countermeasures ship USS Ardent (MCM 12). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Lewis Hunsaker/Released)