The following is an entry for the CIMSEC & Atlantic Council Fiction Contest on Autonomy and Future War. Winners will be announced 7 November.

By J. Overton

“Thank you all for joining me for this this update. I want to start by saying that our thoughts and prayers go out to the families of those killed and injured in this incident. We want to reassure the allied and partner nations impacted by this unfortunate episode that we will do everything we can to mitigate any harm done and restore trust in what his proven a reliable and effective platform. We have already begun an investigation and response to this, and will keep you all informed as we proceed. I’ll just reiterate that at this time, we do not have confirmation that this was anything but a mechanical malfunction. We’ve got time for just a couple of questions. ”

“Thank you, Commander. The spouse of a second class petty officer assigned to this particular program told local media that her husband was arrested by NCIS last night…she said there was an entire SWAT team that sealed off her neighborhood. She said that his personal electronic devices were confiscated, as was a car which he’d purchased last week.”

“I’m not going to speak to that matter, but right now we don’t have any information that it was anything but a mechanical malfunction. These are incredibly well-designed platforms and systems, but they’re also very, very complex. This will of course be investigated as thoroughly as possible. I just want, again, to re-iterate that this seems to be an anomaly in an otherwise reliable system of platforms which has served the security needs of ourselves and many of our allies for several years. We stand with them, ready to help in this trying time.”

“Commander, this is one of the more expensive defense programs ever undertaken by the Department of Defense. Concerns were raised repeatedly about its vulnerabilities. Are those critics now justified?”

“This of course, as I’ve said, is a complex program, but the capabilities remain unmatched by any other system, and we’ve got some fantastic minds doing everything possible to get it back up and running and correct any future deficiencies. We have a level of power projection and speed unmatched in our history, or in the history of any other Navy, and we’re able to carry out those capabilities without putting our people in harm’s way. That, to my mind, is an incredible system well-worth the time and effort to keep it operational and improving.”

“Is there any indication that the manufacturer of this system might be at fault. Under the previous name, the manufacturer of some of system’s components, which were called, let me see, “critical to safe operation, to keeping the human in the decision-process’…that was from a former Marine general…do you believe that those parts could be to blame for this disaster?”

“I’m sorry, I’ll have to address that during our next update. This is an ongoing situation and we’ve got to get back to the operations center. Thank you all.”

***

The platforms, of many shapes and sizes, for swimming and diving and floating and flying, have that clean metallic smell, but not like the copper-taste you get from bleeding gums. It was pure and made one content. That horrid ship smell was all about the people.

***

It only took 2 deployed aircraft carriers to be sunk by non-state actors, and three more to be permanently damaged by similar entities, one including a radiation leak, while in shipyard maintenance. There was nothing tangible, permanent, to retaliate against, except the seemingly corrupt largess afforded to the now-impotent capitol ships that had served so well for nearly a century.

A renewed emphasis, or a myopic obsession to critics, with warfighting as the single mission of Naval forces, made deploying unmanned fleets, systems of systems of platforms, the most reasonable force structure. The Navy was solely to continue politics by other means with violence, a series of duels for sea control and projection of the near-hardest of powers as needed. American humans need not be in harm’s way to provide this new, nor any more involved than absolutely necessary, for this focused naval presence.

***

“Do you take issue with the fact that less than eight percent of naval personnel are currently engaged have duties that traditionally fall into the warfighting or naval realm?”

“I’m not sure where you got that figure, but everyone we have in our service – and don’t get me wrong, it is far fewer people now than we used to have – but everyone is engaged in doing the traditional missions of the United States Navy. The characteristics of those missions have changed, but the essential nature has not.”

***

It only took a few hurricanes and an earthquake to align with the growing political sentiment that Navy bases were impoverished, socialist ghettos of vulnerable, outdated technology to wean the Navy off of the infrastructure teat. Child care, medical care, housing, food, were presumed to be better if one was free to choose one’s own, and the Fleet, as it was, could be controlled almost exclusively far from itself.

***

“There were must dozens of them in canoes and small boats, with like shotguns and harpoons. Came out from the island all at once, like they were trying to surround the fuel ship. Because it was dead in the water from the propulsion casualty, it couldn’t move itself away from unidentified contacts, as it usually would, so it just lit those guys off.”

***

“We don’t have confirmation on the country of origin for those particular offensive assets”

“The reports we have were that these came from inside the U.S. Are you saying you believe they came from overseas? That some other country has that capability without us knowing about it?

“We have a team at the crash and attack site right now, and once they have some answers, we’ll share those.”

***

Providing and maintaining was always about money, and the money flowed like a tidal surge to provide and maintain a Fleet increasingly removed from the cumbersome reflexes and needs of its operators. The rules of war were easier to understand, the range of military operations drastically narrowed, for more efficient, effective, more lethal naval operations.

Mostly unmanned platforms, most personnel scattered across country, swarmed as needed when they actually needed to be somewhere. Personnel support functions were largely left to the individual…no bases, no Fleet concentration, a more agile and strategically-dispersed support structure. The emigration and resettlement of thousands of Navy families, and the reduction and redundancy of the thousands more who was supported them, was covered by per diem and priority air travel as needed. The old Navy towns withered, and cities and communities far from ports or strategic waterways bent over backwards to seduce the unshackled sailors, and sailor’s families, and most importantly, sailor’s consistent income, all now without the hassle of ships/ They offered tax incentives, housing assistance, and all capabilities at their disposal to lure the secure Navy money to the rust belt and dust bowl.

***

“The Southern Poverty Law Center has claimed that at least one of the known sovereignty and secessionist groups claimed that it had unmanned weapons that were programmed to take out what they termed ‘undesirables.’ Because of the ethnic make-up of those killed in this attack, and the cultural make-up of the neighborhood where this took place, it would seem this fits with that modus operandi.”

“I can really speculate right now on who or what cause this to happen, and I can only speak for the Navy…”

“But you did call it an attack?”

“We had several people, including children, killed in that particular incident, and the device or devices which inflicted that harm were acting, or maybe I ought to say, controlled by someone with malicious intent. It wasn’t an accident.”

“Do you believe these attacks are coordinated?”

“Again, I’m not going to speculate on this being an attack, or some kind of deliberate sabotage, or what you have until we have some more details.”

***

The seven cities went dark in phases. The first outage was originally attributed to a winter storm. When the next, also a Midwestern former hub of manufacturing dubbed the “New Norfolk” because of its concentration of Navy families, went offline and unpowered, the real issues began occurring. By the time the last of the Navy towns, all far from water or the operational units they managed, lost power and connection, it was noted that more than half of the U.S. Navy, now mostly charged with monitoring and intermittently maintaining and at times overriding the intelligent, adaptive systems that comprised America’s sea power, was effectively a casualty.

***

“Is the Navy still operational? Overflights from news aircraft suggest that ships are just sailing in slow, circular routes, as if anchored?”

“First, I want to make sure that everyone, everyone understands that our Navy is absolutely operational. We are experiencing some unplanned challenges to our Command and Control functions, but make no mistake; we are where we need to be. I also want to reassure everyone that, with the ongoing power and communications outages, our people in the affected areas are being accounted for. During the decades of continuous global conflict we’ve experienced, we haven’t lost a Sailor to hostile action. That’s an amazing statistic, and one we’re extremely proud of. Our system of systems has given us the ability to mitigate and neutralize to threats as they arise, even in the harshest and difficult environments, without putting our people in harm’s way and much, much quicker and with more agility than with our manned systems.”

“Thank you, Captain, but what we have right now seems to be a breakdown in that system. Several friendly facilities and assets have been damaged or destroyed by U.S. Navy platforms in the last week, and you don’t seem to be able to explain that.”

***

The water went bad, too. The discoloration alarmed the city’s residents, still on generators after the days of inexplicable power outages. Local officials and Congressmen were notified, complaints were broadcast, children became sick. The drinking water pollution was blamed on the poor infrastructure, years of underinvestment, legacy of heavy industry long dormant and never really cleaned. The new Navy towns had not invested their newfound wealth as quickly or responsibly as some said they should’ve. Temporary moves were authorized, a diaspora of what were once sailors scattered across the country, awaiting further instructions.

***

“Thank you all for joining us for this final update we’ll have tonight. First, I’ll summarize what’s been a very eventful week. Several allied nations had facilities and people that were damaged, killed, or injured by strikes that they believed came from our deployed platforms. Several cities in the U.S. suffered massive power and service outages, and others underwent as-yet unexplained explosions which leveled entire city blocks. We know there are theories as to this being some sort of coordinated effort, but as of right now, we have no confirmation or knowledge of what caused any of these issues. We would like to again re-assure our international friends, our allies, and most importantly, the American people, that their Navy was not at fault here.”

“Captain, quick question, so is what you’re referring to as platforms and systems of the Navy, or those actually working and OK now?”

“Our deployed platforms and systems are able to operate, and we have an account of our people, and that all I’m going to say right now about that until we have some more information.”

“Sorry, one more if you will. We know from various credible sources that the Navy is basically what’s been described as ‘offline.’ Is that correct?”

“Look, we are absolutely operational and deployed where we need to be and able to respond. Out of an abundance of caution, we have placed some of our assets in reduced operational status until we learn exactly what transpired over the last several days.”

“Was that at the request of the foreign countries that were attacked by our ships? Do you think this is a rogue actor in our own Navy, or a system malfunction, or have the systems been breached by an outside power?”

“Again, we have no evidence at all that this involved our platforms. We are cooperating fully with the governments that suffered injury to find out exactly what caused those events to take place, but all we have right now are unsubstantiated reports. We have the most far-reaching and capable naval platforms in history, we have a talented and dedicated workforce, and we remain, as we have for decades and centuries, ready to respond to whatever threatens our Nation or our way of life.”

“But, effectively, right now, if you’re not sure who if anyone is the threat, and you’ve suspended operations of what my sources say is the entirety of the Navy’s fully-autonomous Fleet, then I would have to ask how exactly you would do that?”

***

J. Overton is a civilian employee of the Department of the Navy. He is a graduate of the Joint Forces Staff College and the Naval War College, and a veteran of the U.S. Coast Guard. Any opinions expressed here are his own.

Selected inspiration

Fake bomb threat disrupts Naval Base San Diego – http://www.cbs8.com/story/32680303/fake-bomb-threat-disrupts-naval-base-san-diego

Military’s Impact on State Economies – http://www.ncsl.org/research/military-and-veterans-affairs/military-s-impact-on-state-economies.aspx

Unmanned Warrior 2016 – http://www.onr.navy.mil/Media-Center/unmanned-warrior.aspx

Third breakdown in year for $360M US Navy combat ships – http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/29/politics/us-navy-littoral-combat-ship-breakdowns/

Ford Carrier Problems Worse Than LCS: Navy Secretary Mabus – http://breakingdefense.com/2016/10/ford-carrier-problems-worse-than-lcs-navy-secretary-mabus/

The U.S. Navy’s Hamlet Problem – http://warontherocks.com/2015/11/the-u-s-navys-hamlet-problem/

DoD wants to grow total budget, cut personnel costs – http://www.militarytimes.com/story/military/pentagon/2015/02/02/dod-wants-to-grow-total-budget-cut-personnel-costs/22757865/

Infrastructure Report Card – http://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/

Navy’s Top Admiral On Yemen Strikes: ‘Enough Was Enough’ – http://www.military.com/daily-news/2016/10/13/navys-top-admiral-on-yemen-strikes-enough-was-enough.html

“I had forgotten what a beastly thing a ship is, and what a fool a man is who frequents one.” Admiral A.T. Mahan

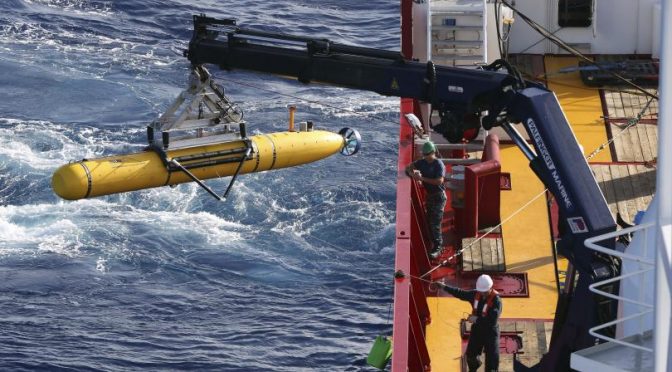

Featured Image: The Bluefin-21 Autonomous Underwater Vehicle is craned over the side of the Australian Defense Vessel Ocean Shield in the southern Indian Ocean during the continuing search for the missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370. (Australian Defence Force/Handout via Reuters)