By Mark Munson

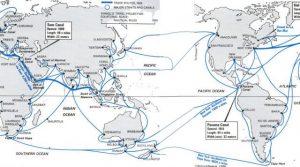

Earlier this year, Admiral John Richardson, the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, released his Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, articulating a vision for how the Navy intends to both deter conflict and conduct “decisive combat operations to defeat any enemy.” Some of the factors it identifies as making the maritime system “more heavily used, more stressed, and more contested than ever before” include expanded trade, the impact of climate change opening sea lanes in the Arctic, increased undersea exploitation of the seabed, and illicit trafficking.

As U.S. Navy operations afloat take place within a more contested maritime system, the need for better “Battlespace Awareness,” one of the three “Fundamental Capabilities” identified in the Navy Strategy for Achieving Information Dominance, is clear. Battlespace Awareness requires a deep and substantive understanding of the maritime system as a whole, including tasks such as the “persistent surveillance of the maritime and information battlespace,” “an understanding of when, where, and how our adversaries operate,” and comprehension of the civil maritime environment.

The U.S. Navy operates across a spectrum ranging from simple presence operations, maritime security, strike warfare ashore in support of land forces, to potential high-end conflict at sea and even strategic nuclear strike from ballistic missile submarines. These operations do not occur in a vacuum, but in a highly complex and dynamic international environment that continues to require real expertise, particularly in its uniquely maritime aspects.

To execute these operations the U.S. Navy needs an intelligence arm employing experts that understand the details of the maritime system and how it can impact naval operations at sea. Three ways to move towards achieving real expertise in the maritime environment include:

- Fielding better analytic tools and using advanced analytics to assist in collection, exploitation, and all-source fusion

- Deploying intelligence analysts and tools to lower echelon units closer to the fight

- Training intelligence personnel in vital skills such as foreign languages

Task 1: Improve Use of Advanced Analytics and Sophisticated Tools

The Design portrays a world in which rapid technological change and broadened access to computing power have narrowed the distance between the U.S. Navy and potential competitors. Wealthy states no longer have a built-in military advantage simply by having access to immense sums of money to invest in military platforms and weapons, including communications and information technology.

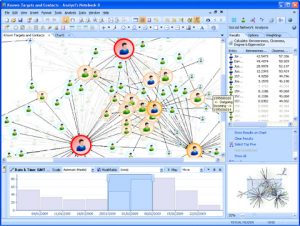

The Design notes that this advantage has been eroded as new technologies are “being adopted by society just as fast – people are using these new tools as quickly as they are introduced, and in new and novel ways.” Virtually anyone now has the ability to access and analyze information in ways that were previously only the preserve of the most advanced intelligence agencies. Indeed, today’s “information system is more pervasive, enabling an even greater multitude of connections between people and at a much lower cost of entry – literally an individual with a computer is a powerful actor in the system.”

This story of rapid technological change does not necessarily have to be one where the leader in a particular field inevitably loses ground to more nimble pursuers. The explosion of “Big Data” gives the U.S. Navy opportunities in which to better understand the maritime system, provide persistent surveillance of the maritime environment, and achieve what the Information Dominance Strategy describes as “penetrating knowledge of the capabilities and intent of our adversaries.”

In addition to an explosion of social media across the planet that provides readily exploitable data for analysis, the maritime environment has its own unique indicators and observables. One example of the ways publicly or commercially available data can be used to develop operationally relevant understanding of maritime phenomena was a 2013 study by C4DS that detailed how Russia has used commercial maritime entities to supply the Syrian government with weapons.

Nation-states and their agencies no longer control the raw materials of intelligence by monopolizing capital-intensive signals intelligence (SIGINT) and imagery intelligence (IMINT) collection platforms or dissemination systems. Anyone can now access huge amounts of potentially informative data. The barrier to entry for analytic tools has drastically declined as well. An organization that can develop analytic tools to exploit the explosion of data could rival the impact that British and U.S. experts in Operations Analysis achieved during the Second World War by improving Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) efforts in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The navy that can successfully exploit the data environment and make it relevant to operations afloat will be better positioned to formulate responses to challenges fielded by potential adversaries often characterized by the now discouraged term “Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2AD).” With the barrier to entry for advanced analytics and use of statistical techniques so low, it would be criminal to not apply cutting edge methods to the various analytic problems faced by intelligence professionals.

Task 2: Employ Intelligence Tools at the Tactical Edge

For a variety of historical and technical reasons, all-source intelligence fusion for the U.S. Navy has generally taken place at the “force” or “operational” levels; typically by an afloat Carrier Strike Group (CSG), Amphibious Ready Group (ARG), or numbered Fleet staff, rather than with the forward-most tactical units. Since at least the Second World War, the U.S. Navy has emphasized the importance of deploying intelligence staff with operational commanders to ensure that intelligence meets that commander’s requirements, rather than relying on higher echelon or national-level intelligence activities to be responsive to operational or tactical requirements.

Since the Cold War, technological limitations such as the large amounts of bandwidth required for satellite transmission of raw imagery had limited the dissemination of “national” intelligence to large force-level platforms and their counterparts ashore. The need to exploit organic intelligence collected by an embarked carrier air wing, coupled with the technological requirements for bandwidth and analytic computing power, made the carrier the obvious location to fuse nationally-collected and tactical intelligence into a form usable by the Carrier Strike Group and the focal point for deployed operational intelligence afloat.

With computing power no longer an obstacle, however, only manpower and the ability to wirelessly disseminate information prevents small surface combatants, submarines, aircraft, and expeditionary units from using all-source analysis tailored to their tactical commander’s needs. The Intelligence Carry-on Program (ICOP) provides one solution by equipping Independent Duty Intelligence Specialists onboard surface combatants like Aegis cruisers and destroyers (CG/DDGs) with intelligence tools approaching the capability of those available to their colleagues on the big decks.

The next step for Naval Intelligence in taking advantage of these new technologies is to determine whether it is best to train non-intelligence personnel already aboard tactical units to better perform intelligence tasks, or deploy more intelligence analysts to the tactical edge of the fleet. Additionally, Naval Intelligence must advocate for systems to ensure that vital information and intelligence can actually get to the fleet via communications paths that enable the transmission of nationally-derived products in the most austere of communications environments.

There is an additional benefit to pushing intelligence analysis down-echelon. The potential for an enemy to deny satellite communications means that the ability of a tactical-level commander to make informed decisions becomes even more important. The Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority argues that “one clear implication of the current environment is the need for the Navy to prepare for decentralized operations, guided by the commander’s intent.”

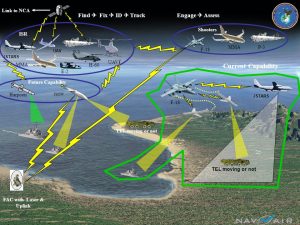

Five of the six steps of the “Kill Chain” or “Dynamic Targeting” process of Find, Fix, Track, Target, Engage, and Assess (F2T2EA) involve intelligence. These include tasks such as detecting and characterizing emerging targets (Find), identifying potential targets in time and space (Fix), observing and monitoring the target (Track), the decision to engage the target (Target), and assessment of the action against the target (Assess). Decentralized operations require the ability to apply more or all steps of the Kill Chain at the tactical edge meaning forward units need an organic intelligence capability.

Enabling tactical units to perform intelligence tasks essential to the Kill Chain at the tactical edge through trained manpower and better intelligence tools could greatly enhance the ability of afloat forces to operate in a what are sometimes described as Disrupted, Disconnected, Intermittent, and Limited bandwidth environments (D-DIL). Potential adversaries have developed a wide variety of capabilities in the information domain that would deny the U.S. military free access to wireless communications and information technology in order to “challenge and threaten the ability of U.S. and allied forces both to get to the fight and to fight effectively once there.” In a possible future war at sea where deployed combatants cannot rely on the ability to securely receive finished national- or theater-level intelligence, the ability to empower tactical-level intelligence analysts is a war-winning capability.

Task 3: Develop Widespread Language and Cultural Understandings

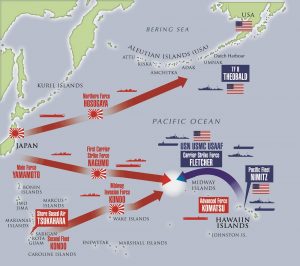

One of the Design’s four lines of effort is to “Achieve High Velocity Learning at Every Level” by applying “the best concepts, techniques, and technologies to accelerate learning as individuals, teams, and organization.” It also calls for a Navy that can “understand the lessons of history so as not to relearn them.” The irony here is that Naval Intelligence continues to ignore one of its most successful education efforts in history: the interwar program that detailed dozens of officers to study Japanese language and culture in Japan (with others studying Chinese and Russian in China and Eastern Europe) during the inter-war years.

Emphasizing the importance of language training and regional expertise would seem obvious goals for Naval Intelligence in light of the Information Dominance Strategy’s call for “penetrating knowledge” and deep understanding of potential adversaries. The direct result of sending men like Joe Rochefort and Eddie Layton to Japan to immerse themselves in that society was victory in the Central Pacific at Midway in June 1942.

While there are language training programs available to the U.S. Navy officer corps as a whole (such as the Olmsted Scholar program), they are not designed to provide relevant language or expertise of particular countries or regions for intelligence purposes. If Olmsted is the way which Navy Intelligence plans to bring deep language and regional expertise into the officer corps, it has done a poor job in terms of ensuring Intelligence Officers are competitive candidates as the annual NAVADMIN messages indicate that only eight have been accepted into the program since 2008.

There has been much debate in recent years, particularly heated in the various, military blogs, over the relative importance of engineering degrees versus liberal arts for U.S. Navy officers. What has been left out of that debate is the obvious benefit associated with non-technical education in foreign languages. A deep understanding of foreign languages and cultures is not just relevant to Naval Intelligence in a strictly SIGINT role. Having intelligence professionals fluent in the language of potential adversaries (and allies) allows deep understanding of foreign military doctrine and the cultural framework in which a foreign military operates.

Foreign language expertise for a naval officer is not a new concept. In the late nineteenth century prospective Royal Navy officers had to prove they could read and write French in order to achieve appointment as a cadet, and officers were encouraged to learn foreign languages. Interestingly, the U.S. Naval Academy does not require midshipmen majoring in in Engineering, Mathematics, or Science to take foreign language courses.

Conclusion

Naval Intelligence is vitally relevant to the U.S. Navy’s afloat operations, but can be significantly improved by taking advantage of the current technological revolutions in data and data exploitation. While the Design uses new terminology and does not address intelligence’s role specifically, the core missions and tasks of Naval Intelligence remain the same as they were in 1882 when Lieutenant Theodorus Mason started work at the newly established Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). Maritime experts can provide the decisive edge in combat operations through more advanced and sophisticated tools, by pushing intelligence expertise to the tactical edge to advise front-line commanders and mitigate new high-end threats, and by applying more detailed knowledge of the languages and cultures of potential adversaries in the most challenging environments.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a naval intelligence officer assigned to United States Africa Command. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Featured Image: 140717-N-TG831-028 WATERS TO THE WEST OF THE KOREAN PENINSULA (July 17, 2014) Operations Specialist 1st Class Brian Spear, from Senoia, Georgia, assigned to the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Kidd (DDG 100), stands watch in the combat information center. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Declan Barnes/Released)