This article originally featured in The Submarine Review and is republished with permission.

By Ryan Hilger

Captain Gallery picked up the radio: “Ride ’em cowboy.” Lieutenant David’s boarding party worked quickly to clear the submarine and make up Pillsbury‘s towline, despite the rudder being jammed hard over and the submarine still making ten knots. Chatelain and Jenks broke off to pick up survivors. Commander Trosino, Guadalcanal‘s Chief Engineer, and another boarding party made for the submarine to begin salvage efforts. Flooded compartments and potential booby traps slowed repair efforts. Pillsbury radioed back that the destroyer didn’t have the power to maintain the tow and keep the submarine afloat. Gallery ordered Guadalcanal into position, taking up the tow. After a challenging several days, U-505 was turned over to Naval Operating Base Bermuda for evaluation.1 The capture of U-505 on June 4th, 1944 was the zenith of Allied anti-submarine warfare efforts, indicating that German submarines would not play a decisive role in what became the final year of the war.

The Battle of the Atlantic spanned the entire duration of the war, stressing the endurance and resourcefulness of all involved, from fleet commanders to heads of state to cryptographers to ordinary seamen in anti-submarine trawlers and U-boats everywhere. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, worth quoting at length here, frames the issue:

“The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril. Invasion, I thought, even before the air battle, would fail. After the air victory it was a good battle for us. We could drown and kill this horrible foe in circumstances favourable to us, and, as he evidently realised, bad for him. It was the kind of battle which, in the cruel conditions of war, one ought to be content to fight. But now our life-line, even across the broad oceans, and especially in the entrances to the Island, was endangered. I was even more anxious about this battle than I had been about the glorious air fight called the Battle of Britain.2

This unforgiving war at sea challenged the conventions of Mahan and Corbett on the meaning of sea control and, in that philosophical struggle, informs strategic thought as we face asymmetric threats abroad. Several anecdotes from this long, grinding campaign provide insights as American naval forces grapple with the nascent possibility of a modern, protracted war of attrition at sea.

The Essentiality of War Games

Convoys HX-229 and SC-122 were eastbound for Britain. Their air cover had lapsed until the Liberator squadron in Iceland could reach them. The base courses of the convoys were continually altered around wolfpack locations revealed by Ultra, the Allied radio intercept and cryptanalysis program.3 But this time, the routings had placed them on a collision course with each other and three wolfpacks, the U-boats still high after battering SC-121 and HX-228 the day prior. On March 16th, 1943, they “hurled themselves like wolves first on the Halifax convoy, then on the Sydney convoy as soon as it was sighted, and finally on the great combined mass of ships.”4 38 U-boats exploited the next three days, relentlessly attacking day and night, sinking 21 of 61 ships.

The massacre of convoys SC-122 and HX-229 began twenty-five years prior to the coup de main, southeast of Sicily with then Lieutenant Commander Karl Doenitz in UB-68 and his near death at the hands of a British warship escorting a convoy just out of the Suez Canal. UB-68 was hit, but managed to blow her ballast tanks to the surface, where the submarine sank beneath him, the convoy continuing on to Britain unmolested. At that moment, floating in the warm Mediterranean waters with his lifejacket and a piece of salvaged cork, Doenitz recalls,

“That last night, however, had taught me a lesson as regards basic principles. A U-boat attacking a convoy on the surface and under cover of darkness, I realized, stood very good prospects of success. The greater number of U-boats that could be brought simultaneously into the attack, the more favorable would become the opportunities offered to each individual attacker.”5

The seed of wolfpack tactics had been planted. Several other German submariners would come to the same conclusion independently during the Great War, but none seemed to gain traction with the German High Command. Revolutions do not come about overnight.

Doenitz would rise slowly during the interwar years, eventually being selected to take over the first reformed U-Boat Flotilla in 1935. He found like-minded officers under his command and proceeded to develop cooperative tactics. In 1937, during the German Armed Forces Maneuvers, U-boats operated for the first time together, tasked to “locate, concentrate and attack an enemy formation and convoy somewhere on the high seas to the north of the coasts of Pomerania and West and East Prussia.”6 The operation was wildly successful, and U-Boat Command continued with large-scale exercises into 1939, including under the review of Admiral Raeder, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, until the Second World War started a few months later. The exercises provided Doenitz with the opportunity to further refine the span of control, communications, and tactics the U-boats would need in combat to bring wolfpacks to their highest potency.

Interestingly, Doenitz reveals that the British were caught largely unaware in the first year and a half of the war that the Germans were employing cooperative tactics against their convoys. Citing Captain Stephen Roskill, the eminent British naval historian, Doenitz writes,

“But as the numbers controlled by Admiral Doenitz increased, he was able to introduce attacks by several U-boats working together…The change caught us unawares…but the Development was, from the British point of view, full of the most serious implications since the enemy had adopted a form of attack which we had not foreseen and against which neither tactical nor technical countermeasures had been prepared.”7

This is shocking revelation for the preeminent Navy in the world at the outbreak of the war. The roots of this negligence, Roskill continues, are found in the interwar period:

“When British naval training and thinking in the years between the wars are reviewed, it seems that both were concentrated on the conduct of surface ships in action with similar enemy units and that the defence was also considered chiefly from the point of view of attack by enemy surface units.”8

Doenitz theorizes that the invention of active sonar lulled the British into thinking that oceans had been made transparent and that the submarine became instantly irrelevant.9 In conjunction with the technological advances, the development of wolfpack tactics also reveals the grave threat presented by sclerotic British thinking during peacetime. The bold and decentralized command of the Nelsonian navy had slowly devolved over a century into untested, theoretical doctrine, the fleet “[enjoying] a peace routine and that its title of Mistress of the Seas [not having been] seriously challenged.”10 Arthur Marder relates the state of the Royal Navy in 1897 prior to the reforms of Admiral Jackie Fisher: “the British Navy at the end of the nineteenth century, numerically a very imposing force, was a drowsy, inefficient, moth-eaten organism.”11 The ramifications of stultified strategic thought and the unacknowledged strategic draw at Jutland in 1916 further ossified British tactical development for the next twenty years.12 Doenitz, on the other hand, presents a case for the importance of war games for tactical and operational developments, and the consequences for the navies that spend the peacetime steaming around the world to “show the flag,” fueled by achievements of past wars while the guns rust from lack of meaningful combat exercises.

Tactical Innovation and Credulity in Technology

In the Clausewitzian sense, the nature of the Battle of the Atlantic changed little over the course of the war. The merchant ships plodded along the routes provided by the Allied convoy routing commands, ever in existential peril, while the U-boats prowled about the waves in search of prey. However, a closer examination of the operational level of war provides a plethora of examples of technical innovation—focusing on the development of active sonar here—the first applications of operations research, and a clear warning about immature faith in technological advancements without any corresponding evidence of efficacy beyond first principles or development of doctrinal employment.13

The first hydrophones were fitted to warships for submarine detection as early as 1915, but provided such inaccurate bearings, and without a suitable close attack weapon, to render then operationally irrelevant. In September 1918, the British formed a scientific committee, the Anti-Submarine Division International Committee (Asdic) to develop echo-ranging methods to fix a submarine’s position. The system was fielded shortly before the war ended in 1918 and continued to be developed during the interwar years, now able to provide both bearing and range.14 Prime Minister Winston Churchill recalls his experience with the refined Asdic sets:

“On June 15, 1938, the First Sea Lord took me down to Portland to show me the Asdics [italics original]… Standing on the bridge of the destroyer which was using the Asdic, with another destroyer half a mile away, in constant intercourse, I could see and hear the whole process, which was the Sacred Treasure of the Admiralty, and in the culture of which for a whole generation they had faithfully preserved.”15

The British began World War II with 220 sets installed on various small combatants and trawlers, with many more sets waiting for ships to install them on—Churchill’s maritime building program would take a year or two more to reach fruition.16 Of note, Churchill does not record the doctrinal development of anti-submarine warfare in the same way that Doenitz discussed the refinement of tactical and operational doctrine for submarine wolfpacks. Doenitz records in his Memoirs the seeming blind faith by the British that the new technology would render submarines useless as a weapon of war: “in 1937 the Admiralty reported to the Shipping Defence Advisory Committee that ‘the U-boat will never again be capable of confronting us with the problem with which we found ourselves faced in 1917.”17 Churchill, at the outbreak of the war, agreed:

“I had accepted too readily when out of office the Admiralty view of the extent to which the submarine had been mastered. Whilst the technical efficiency of the Asdic apparatus was proved in many early encounters with U-boats, our anti-U-boat resources were far too limited to prevent our suffering serious losses.”18

This failure to grasp the limitations of the new technology, both in technical performance and the employment of it, required a rapid development program and the founding of operations research.19

The British anti-submarine forces had dwindled in the interwar period to less than ten percent of the forces available to the Allies at the signing of the Armistice in Versailles.20 The shortage would cost them dearly in operational tempo and merchant shipping lost while waiting for the Americans to enter the war or for their own shipbuilding program to start delivering. Even with Asdics on their warships, merchant shipping losses totaled more than 900 ships and 4,000,000 tons by the end of 1940.21 Yet a significant inventory of Asdics still sat on shelves, waiting for ships to enter service, and in that lies another lesson for gaining superiority in the war of attrition—cooperation with allies.

Allies and the Fielding of Capabilities

In May 1940, Churchill first laid bare the British needs to President Roosevelt: “All I ask now is that you should proclaim non-belligerency, which would mean that you would help us with everything short of actually engaging armed forces. Immediate needs are, first of all, the loan of forty or fifty of your older destroyers to bridge the gap…”22 The use of mothballed destroyers seems a logical and prudent policy to pursue, but the American political scene then, records Samuel Eliot Morison, was still rooted in quasi-pacifism.23 It would take President Roosevelt a great deal of time and political capital to secure the Lend-Lease program.

Churchill pressed again several months later, indicating how their mutual, albeit still private, goals could be served: “We can fit [the older destroyers] very rapidly with our Asdics, and they will bridge the gap of six months before our war-time new construction comes into play.”24 This string of discussion would continue between Roosevelt and Churchill for the remainder of 1940, even with the offer of British crews to man and transport the destroyers across the Atlantic. President Roosevelt would eventually find a loophole in the Neutrality Act of 1939 and sign a bilateral agreement with Churchill on September 2, 1940, on the trade of fifty older American destroyers for 99-year leases for naval bases from Great Britain. British sailors would bring the American ships back to life and take the fight to their common enemy in a shining example of the importance of bringing capabilities rapidly to bear in a war of attrition to gain a tactical edge.

The Unbiased Tyranny of Geography

It is rare for terrain in war to be so unfavorable to the contesting parties. Both Sun Tzu and Clausewitz speak of the ground as preferential to a particular side depending on the value accorded to it.26 The sea, however, retains the ability to be the great equalizer, especially in the modern, globalized era, while simultaneously being supremely cruel to those who lose their respect for it. The Atlantic Ocean and the martial contest for it offered different challenges for all involved—British, German, and American. For Britain, the sea was survival. For Germany, the sea presented the longest contiguous battlefront. For the Americans, the sea represented the lifeline to Britain, under constant threat which, for the majority of the war, they lacked the necessary escorts to fully protect. Not until the summer of 1943 did the Allies begin to achieve sea control. Corbett puts this battle into theoretical prospective:

“By general and permanent control [of the sea] we do not mean that the enemy can do nothing, but that he cannot interfere with out maritime trade and overseas operations so seriously as to affect the issue of the war, and that he cannot carry on his own trade and operations except at such risk and hazard as to remove them from the field of practical strategy.”27

Corbett, vice Mahan, defines the heart of the struggle: “By occupying her maritime in which they terminate we destroy the national life afloat, and thereby check the vitality of that life ashore so far as the one is dependent on the other.”28 Britain needed the sea for survival and Germany rightly discerned that the sea was the key to Britain’s destruction. Thus, the Battle of the Atlantic was not simply another battle on the road to victory, but rather an extended campaign at the operational level of war, and a matter of national strategic policy for all contestants.

Churchill, never shy at communicating the necessity of commerce to the survival of Britain, again indicates the British national policy to President Roosevelt: “North Atlantic transport remains the prime anxiety… I am sorry about [stopping food subsidies to Eire], but we must think of our own self-preservation, and use for vital purposes our own tonnage brought in through so many perils.”29 The American policy, still protected by pre-war isolationist policies, took more time to develop. Admiral Stark, then the Chief of Naval Operations, submitted his thoughts on American grand strategy to Navy Secretary Knox in late 1940: “Our major national objectives in the immediate future might be states as preservation of the territorial, economic, and ideological integrity of the United States…the preservation of the disruption of the British Empire with all that such consummation implies…”30 These views would be fully developed and codified in the American-British Conversation (ABC) agreements, first completed in March 1941.

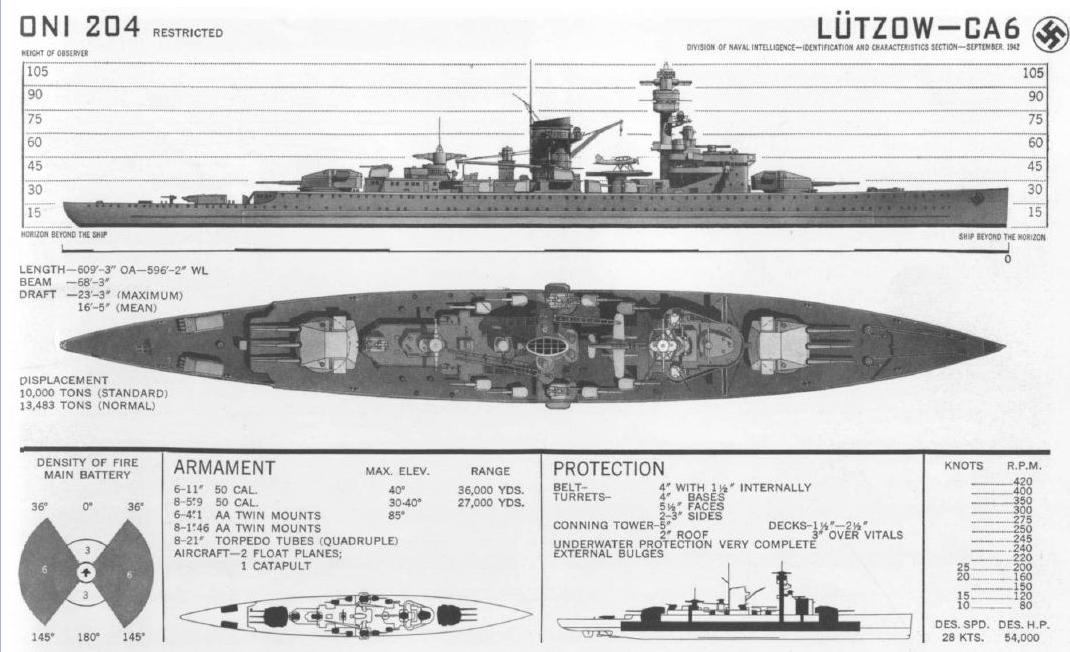

In the years prior to the war, Germany began finalizing how they would structure the Navy to strangle the British islands. Admiral Erich Raeder, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, saw the unfolding situation plainly: “Britain imported fifty million tons of goods annually and her very existence depended on the keeping open of her supply lines. An effective attack on Britain’s oversea supplies therefore had to be the main aim of any German naval building programme.”31 In contrast, Raeder believed that “[as] for our surface forces, they were so inferior to the enemy in strength and numbers that about all they could hope to do was go down fighting.”32 Raeder has grasped the four Clausewitizan factors of success in war.33 This attitude shaped the shipbuilding program in the final years of prior to the war, resulting in Germany beginning the war with near four times as many submarines as all surface ships combined.34 Geography shaped the battle, forcing widely distributed forces against a highly distributed threat.

For Germany, though, the execution of the maritime strategy would be anything but trivial.35 The development of wolfpack tactics and the technological advances added the efforts at the tactical and operational levels, but the distances involved pressed the strategy to its limits. Due to distance, geographic positioning, maintenance, and training cycles, only eight of the 57 U-boats in commission could be engaged in the Atlantic for the first year of the war. The early fall of France and capture of the French ports on the Bay of Biscay provided a significant improvement, both in geographic position as well as the addition of dockyards and repair facilities. Doenitz summed up the strategic value of this gain:

“Before July 1940 the U-boats had to make a voyage of 450 miles through the North Sea and round the north of Great Britain to reach the Atlantic. Now they were saving something like a week on each patrol and were thus able to stay considerably longer in the actual area of operations. This fact, in its turn, added to the total number of U-boats actively engaged against the enemy. It was thanks to these direct efforts of the possession of the Biscay bases….”36

The improvement in position, combined withe the building program, allowed Germany to eventually keep nearly one hundred U-boats at sea.

Control of the Sea

Captain Roskill records that the utter destruction of HX-229 and SC-122 “made a profound impression upon the British Admiralty, which later recorded that ‘the Germans never came so near to disrupting communication between the New World and the Old as in the first twenty days of March 1943.'”37 Yet the German euphoria and Allied dejection would decisively reverse in the subsequent two months as the Allies shifted the balance of power with the introduction of additional long-range aircraft. Roskill recalls,

“[A] sweeping victory was gained in April and May; and of the 56 U-boats sunk in those two months 36 were destroyed by ships and aircraft operating as convoy escorts or in support of convoys. Doenitz thereupon abandoned the battle of the convoy routes. The reason was, so he said, that his losses had increased to about one-third of all the submarines at sea— losses much too high.”38

Doenitz and his submarines would never again gain the upper hand.

The Allies would subsequently introduce greater measures to fight the U-boat menace, including the introduction of the hunter-killer groups like the one that captured U-505. The industrial machine in both Britain and the United States would pick up steam, churning out Liberty ships every 42 days and escorts even more rapidly, turning the tide of the battle through sheer numbers.39 Control of the sea in the Corbettian sense would be achieved, but that control did not mean that hostilities would cease—quite the contrary. Both sides would continue to feed grist to the millstone until the end of the war; each side would lose roughly 30,000 Sailors or airmen.40 Tenuous control at best.

The Battle of the Atlantic contains many more lessons for control of the sea in a war of attrition.41 But the essence of the battle should alert strategists to the necessity of exercises in merging revolutionary technologies into new doctrine and the need to deploy capabilities, not just platforms. Above all, strategists need to know that establishing and maintaining maritime superiority in today’s environment, as in the Battle of the Atlantic, is more than the capacity to destroy the enemy in a fleet action—the Battle of the Atlantic repudiated Mahan. Captain Wayne Hughes provides the simple summation: “Naval battle is attrition centered. Victory by maneuver warfare may work on land but it does not at sea. At sea, first effective attack is the aim of every tactical commander.”42 An enemy can fight a war of attrition at sea, a guerre de course in which he has many advantages and vulnerabilities. Force composition cannot be determined without due regard for the economic implications of the naval role in national strategy. Commanders must continue to innovate, experiment with new technologies, and evolve how they wage war at all levels. Failure to stay abreast of technology or properly incorporate it will engender strategic surprise on the battlefield, thus driving your forces from the sea, or to the bottom of it.

Lieutenant Commander Ryan Hilger is an Engineering Duty Officer and former submariner. These views are presented in a personal capacity.

References

1. “Oral History-Battle of the Atlantic. Recollections of Captain Daniel V. Gallery, USN, commander of USS Guadalcanal Task Group concerning the capture of German submarine U-505 on 4 June 1944,” Naval History and Heritage Command, August 2, 2002, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/oral-histories/wwii/recollections-of-captain-daniel-v-gallery.html

2. Churchill, Winston. The Second World War, Volume II: Their Finest Hour. London: Cassell & Co, Ltd., 1949, p. 529.

3. The Ultra program was the highly secretive cryptanalysis efforts to break German radio encryption. See also “Ultra and the Battle of the Atlantic.” National Security Agency. https://www.nsa.gov/news-features/declassified-documents/cryptologic-spectrum/assets/files/Ultra.pdf. Accessed on February 6, 2017.

4. Doenitz, Karl. Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days. Boston, MA: De Capo Press, 1997, p. 329.

5. Ibid, p. 4.

6. Ibid, p. 21.

7. Ibid, p. 22.

8. Ibid, p. 23.

9. Ibid.

10. Marder, Arthur. “Admiral Sir John Fisher: A Reappraisal.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, March 1942, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1942-03/admiral-sir-john-fisher-reappraisal.

11. Ibid.

12. See also: Gordon, Andrew. The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013 and Hughes, Wayne. Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000. Chapters 2 and 3 of Hughes, in particular, have a concise discussion of this topic.

13. This essay focuses on the development of active sonar, but the list can certainly be expanded to include technological developments on both sides: radio direction finding, acoustic torpedoes, an air induction mast, or snorkel, the mathematically-based attack tactics for bombers and depth charging, and the prodigious industrial efforts of the American shipbuilding industry to churn out the Liberty ships and destroyer escorts. A myriad of resources provide greater information on these individual developments.

14. Sternhell, Charles M. and Alan M. Thorndike. “Antisubmarine Warfare in World War II.” Operations Evaluation Group, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Washington D.C., 1946, p. 2.

15. Churchill, Winston. The Second World War, Volume I: The Gathering Storm. London: Cassell & Co, Ltd., 1948, pp. 127-8.

16. Sternhell and Thorndike, p. 2.

17. Doenitz, p. 23.

18. Churchill, p. 325.

19. See Part II of Sternhell and Thorndike for an excellent exposition on the various scientific approaches to anti-submarine warfare during the Battle of the Atlantic. This section truly summarizes the first operational application of operations research, at the time a nascent field. See also: Koopman, B. O. Search and Screening: General Principles with Historical Applications. New York, NY: Pergamon Press, 1980. Budiansky, Stephen. Blackett’s War: The Men Who Defeated the Nazi U-Boat and Brought Science to the Art of Warfare. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 2013.

20. Sternhell and Thorndike, p. 2.

21. Churchill, p. 569 and Churchill, Volume II: Their Finest Hour, p. 639.

22. Churchill, Volume II: Their Finest Hour, p. 23.

23. Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume I: The Battle of the Atlantic, 1939-1943. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2001, p. 33.

24. Churchill, p. 117.

25. Ibid, p. 361.

26. Tzu, Sun. The Art of War. Edited by Basil Liddell Hart, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1971, pp. 114-115.

Clausewitz, Carl. On War. Edited by Peter Paret. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 345.

27. Corbett, Julian S. Principles of Maritime Strategy. Mineola, NY: Dover Books, 2004. pp. 102-3.

28. Ibid, p. 91.

29. Churchill, Volume I, pp. 535-6.

30. Morison, p. 42.

31. Raeder, Erich. Struggle for the Sea. London: William Kimber and Co. Ltd., 1959, p. 128.

32. Ibid, p. 136.

33. Clausewitz, p. 261.

34. Showell, Jak Mallmann. Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs 1939-1945. Gloucestrshire: The History Press, 2015, p. 34.

35. See also: Showell, Jak Mallmann. Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs 1939-1945. Gloucestrshire: The History Press, 2015. This collection comprises the surviving documents that Doenitz ordered preserved, not destroyed, when he headed the German government at the end of the war. The volume shows the difficulties that the German Navy faced in executing the naval component of German national strategy given Hitler’s general disposition toward ground forces and the influence of Hermann Goering and the German Air Force.

36. Doenitz, p. 112.

37. Ibid, p. 329.

38. Roskill, Stephen. “CAPROS not Convoy: Counterattack and Destroy!” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, October 1956, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1956-10/capros-not-convoy-counterattack-and-destroy.

39. Winston, George. “The Amazing Achievement of Baltimore’s Shipyards: One Liberty Ship Every 42 Days.” War History Online. November 24, 2015. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/military-vehicle-news/baltimores-liberty-ship-legacy.html

40. Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume X: The Battle of the Atlantic Won, May 1943 – May 1945. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2001, p. 363.

41. See also: Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume X: The Battle of the Atlantic Won, May 1943 – May 1945. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2001, pp. 361-4. Here Morison draws conclusions about the American role in the battle, which he generally confines to the development and deployment escort carrier groups. He writes that the British and Canadian forces were on the whole more skilled and experienced than American forces, and that British and Canadian forces did more to contribute to victory in the Atlantic than did the United States. His full conclusions about the battle are worthy fodder for strategists to consider.

42. Hughes, Wayne. Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat. Annapolis, MD: Naval

Featured Image: Colorized photo of German U-boats. (Public Domain)