Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Blake Herzinger and Elee Wakim

“Having therefore no foreign establishments, either colonial or military, the ships of war of the United States, in war, will be like land birds, unable to fly far from their own shores. To provide resting places for them, where they can coal and repair, would be one of the first duties of a government proposing to itself the development of the power of the nation at sea.”–Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Seapower Upon History, 1660-1783

Since before the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the United States has determined that “American security, economic prosperity, and values would be fundamentally put at risk if a rival hegemonic power dominated the Pacific.” The United States has ensured this end by various ways and means since the defeat of the Spanish Empire in 1898. Given the vast distances between continental North America and the western Pacific littorals, the United States’ ability to project power and influence is necessarily based upon expeditionary maritime capabilities and globe-spanning military infrastructure. The cornerstone of this power projection complex in the western Pacific is forward deployed military forces, which are in turn enabled by the availability of proximate and friendly basing in theater. However, the ability of the United States to sustainably conduct expeditionary operations in the strategic chokepoints and littorals of Asia could crumble in the absence of the allied access it has come to rely on.

Access to the local, dual-use infrastructure the United States enjoys today is the result of years of sustained investment of all elements of American power to align mutually interested states into a network that allows the United States to project power from their shores. In recent years, these investments have been diffused across a broad number of states, such that the mortar is crumbling under a lack of recapitalization. This critically enabling influence of forward partners is waning as the PRC rapidly expands its influence, turning the political will of forward allies into strategic chokepoints of another sort.

The U.S. is therefore forced to consider whether those locations it relies on to sustain its overseas presence – whether by formal agreement or informal association – would still be available in the event of a military confrontation between the United States and China. How would this sudden loss of access affect how the U.S. fights as a force and projects power into the western Pacific?

While there are many detractors who will lampoon the proposition that the U.S. would ever be deserted by its overseas partners – perhaps citing years of historic partnership and common interest – it is important to ask if the U.S. is willing to bet the farm on this untested and assailable assumption. If not, what must the United States do in order to hedge against the loss of its heretofore unchallenged access to the western Pacific littorals and attendant infrastructure?

Access for What?

The American military presence in the Indo-Pacific largely reflects the vestiges of the Cold War and has its roots in the exigencies of conflicts ranging from World War Two to Vietnam. The United States has military relationships with nearly every country within the First Island Chain, ranging from limited partnerships to full military alliances. U.S. security cooperation plans keep most of those relationships on ever-increasing trajectories of investment, but this may be more a function of inertia than strategic acumen. American joint doctrine makes clear that the creation of access for U.S. forces is one of the three reasons for conducting security cooperation operations. This investment has created an unparalleled network of ports and airfields capable of supporting U.S. expeditionary operations and logistics in unchallenged environments (see Table 1).

| Table 1: U.S. Military access arrangements among South China Sea littoral states | |||

| Country | Acquisition & Cross Servicing Agreement (ACSA) | Hosts U.S. Base or Rotational Deployments | Routine Base Access |

| Brunei | x | ||

| Cambodia | |||

| Indonesia | x | ||

| Malaysia | x | ||

| Philippines* | x | x | x |

| Singapore | x | x | x |

| Taiwan | |||

| Thailand | x | x | |

| Vietnam | |||

*In question after cancellation of U.S.-PHL Visiting Forces Agreement

As the United States and China continue to jostle for position, allies and partners are pulled in separate directions. The long-relied upon American security guarantee is confronted by China’s growing military and economic strength, and geographic proximity. Despite the deep history and genuine bonhomie between the U.S. and its security partners, this confrontation jeopardizes the carefully-laid peacetime network built over decades, which must be carefully regarded as great power competition in the Indo-Pacific continues to intensify.

For those that might decry this argument as alarmist or discounting years of partnership, consider the state of the U.S.-Philippines alliance. Linked by a Mutual Defense Treaty, the two states’ militaries have stood prepared to fight shoulder-to-shoulder for decades. In February of this year, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte announced his intention to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement that, in large part, undergirds that same alliance. The U.S. expectation of access, a key planning consideration, evaporated overnight.

Looking back three decades, we see the U.S. military evicted from its Philippine bases in Clark and Subic Bay in a similar vein. President Duterte has been vocal since his election regarding his intention to rebalance Philippines’ foreign relations, with the subtext being a move closer to China. It is easily posited that this decision is largely motivated by the expectation of economic benefit and uncritical security assistance. And this is coming from one of the supposedly closest U.S. allies in Southeast Asia.

What then of the defense partnership with Thailand, where the U.S. has long-relied upon the U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield to support combat operations, from Vietnam to Afghanistan? Thailand’s military is now led by openly pro-China officers and their branches have recently concluded a number of high-profile purchases of major weapons platforms from China. Should the U.S. and China enter into hostilities, would Thailand offer the use of its strategic airfield with the knowledge that it might be severing ties to the source of its own military equipment? This is, of course, only the military aspect. China is also Thailand’s largest trading partner.

If the depth of U.S investments and shared interests with its closest Southeast Asian allies are crumbling during peacetime, what then does this portend for access with less formally aligned states during open conflict with the PRC? In the face of mounting evidence to the contrary, should the U.S. government continue to rely on the prospect of unfettered access to logistical support and conduct offensive operations, as it has for the past 30 years? Or is it setting up the possibility of the Joint Force having to play a scratch game as its forward elements are ejected by non-belligerents at the outset of a conflict?

All Dressed Up with Nowhere to Go

Spanning from critical repair and replenishment functions to overflight permissions and divert airfields, the premise of access in nations such as Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, Japan, Korea, and elsewhere is crucial to American operational plans. This loss will reduce the force generation capacity in theater, constrict avenues of approach, constrain operational flexibility, render the forward logistics chain brittle, and introduce friction into the crucial opening hours of a conflict as American forces potentially scramble to adjust to a new, unpracticed reality.

One of the first and most likely casualties to a restriction on access is the loss of crucial airfields. These airfields enable everything from air dominance operations and anti-submarine warfare, to battlefield awareness and transportation of personnel and material. While their loss does not mean that the United States and coalition partners will be unable to conduct air operations within the First Island Chain, both the number of sorties and on-station time will be significantly reduced as aircraft have to fly from more distant locales. This in turn will strain the U.S. aerial refueling capability, which will be hard pressed to sustain long range operations as well as facilitate reinforcement transfer to the theater. Further, it raises the specter of increased losses, as damaged aircraft or those without return tanker support will be without a proximate place to land. Finally, it will curtail the effectiveness of the forward arming and refueling points (FARPs), which are currently touted by the Joint Force as a way of conducting distributed and short duration aviation operations from non-fixed points.

Singapore offers a multi-faceted case study. Viewed by many as the Southeast Asian partner closest to the United States, Singapore hosts the U.S. Navy command responsible for organizing logistics operations across the U.S. Seventh Fleet, as well as the headquarters which controls U.S. Navy Littoral Combat Ships in the region. As a related aside, the U.S. military presence in Singapore began when Singapore offered its Sembawang facility to the U.S. Navy when it was evicted from its bases in the Philippines in 1993. U.S. ships today are rotationally deployed to Singapore’s Sembawang port facility, and the Changi Naval Base was expanded for the express purpose of accommodating U.S. nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. U.S. P-8A routinely fly from Singapore’s Paya Lebar Air Base.

However, Singapore’s Prime Minister has already warned the U.S. publicly that forcing a choice between supporting the U.S. or China would be “very painful,” pointing out that, notwithstanding Singapore’s partnership with the United States, its economy is far more reliant on China. Singapore prides itself on charting a balanced course between the two competing superpowers and in the event of a U.S.-China war, its preferred position would be neutrality. The port, airfield, and logistics support currently enjoyed by the United States would place Singapore’s domestic infrastructure at unacceptable risk during a major conflict with China. Unless Singapore’s interests were directly affected by this hypothetical war, it seems very likely that U.S. forces would politely be asked to relocate, and by a partner proximate to one of the most significant chokepoints in the region.

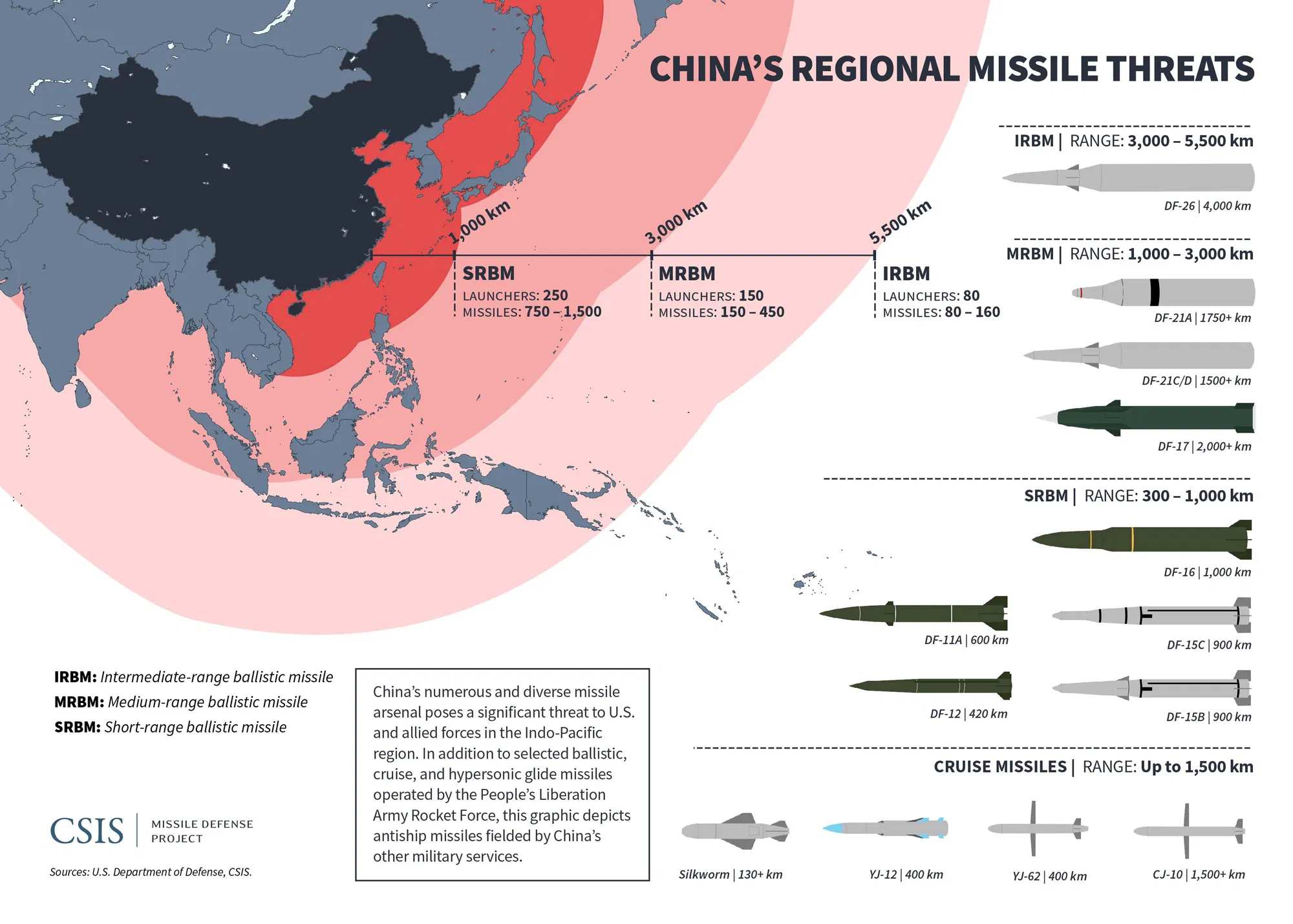

It is not too much of a stretch to imagine that non-belligerents, under PRC pressure and having curtailed access to their territory, might conceivably restrict permission to overfly their country as well. This would severely limit the avenues of approach of air power and reinforcements flowing into theater as they are forced to detour around the airspace of erstwhile partners. This in turn would allow the PRC to concentrate its forces – backed up by a mainland-based reconnaissance strike complex (see Figure 1) – on these narrow vectors, such as the Luzon and Singapore straits. While coalition aircraft could overfly this previously friendly territory, to do so might invite armed challenge in response to violations of the nation in question’s sovereignty. It also risks poisoning the narrative concerning the justification of the conflict.

The issues attendant with the loss of access are further compounded by an insufficient amount of long-range munitions. While the United States plans to buy an additional 1,625 long range “missiles with ship-killing potential” between Fiscal Year 2020 and 2025, it has only acquired approximately 1,050 weapons since Fiscal Year 2011. Comprising the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), Standard Missile-6 (SM-6), and Maritime Strike Tomahawk (MST), the latter two weapons are multi-purpose, and consequently may be in high demand across a globe spanning force. When considered in the context of a dearth of available shipboard launchers, the potential loss of proximate locations for USMC expeditionary advanced bases, a lack of a robust mining capability, a fragile logistics chain, and an inability to conduct forward reloading of VLS, the reduced sortie rate induced by the loss of access becomes very problematic indeed. While the Defense Department is working to address many of the identified issues, they are still extant today, raising the specter of the United States being unable to achieve its stated goal of deterrence by denial.

Where Do We (Figuratively) Go From Here?

If we accept the premise that access to forward fighting positions may be curtailed in the event of a conflict with the People’s Republic of China for foreign political or diplomatic reasons, then the United States must make prompt investments to maintain credible deterrence. While the Pacific is primarily a maritime theater – indeed, as Bryan McGrath wrote, “if it is […] the desire of the United States not to be displaced, American seapower will have to shoulder a disproportionate share of the load” – the response will require investments across the Joint Force. While some of these investments are already being made, not all are being undertaken with sufficient alacrity or scale, and are likely to be high on the divestment list in the event of declining defense budgets. Many of these initiatives – from sealift recapitalization to additional defenses for Guam – have been talked about for years, during which little to no action was taken. If the United States is to maintain a credible deterrent posture vis-a-vis the PRC, investments must be made in this “priority theater” promptly and at scale. They will not only hedge against a loss of access, but may sufficiently reassure regional partners to ward off such an outcome.

The United States will have to examine the difficult prospect of violating the sovereignty of non-belligerents in a time of war. There may well come a point when the Joint Force will have to seize key positions along the South China Sea periphery – for example, in the Philippines, Indonesia, or Malaysia – for short durations in order to facilitate operations. These operations could conceivably span from landing covering forces for chokepoint transits, or establishment of sea denial positions, to replenishment of naval vessels in calm bays or setting up FARPs in austere locales. This introduces a number of issues, including raising the risk of severe reputational damage – possibly poisoning popular will against the U.S. war effort – and the prospect of the violated party’s forces challenging these temporary occupations with force. Preparing informal access arrangements, messaging narratives, and seizure CONOPs will be vital to achieving temporary operational access when it is otherwise denied. A unified joint Foreign Area Officer team will need to stand prepared to broker these agreements when the time comes.

Japan’s invasion of the Malayan peninsula in 1941 perfectly illustrates the consequence of the failure to prepare for this scenario. Britain, unwilling to violate Thai neutrality, allowed the Imperial Japanese Army to conduct a mostly-unmolested amphibious landing which would lead to the fall of Malaya 73 days later.

Conclusion

Hedging against the risk of an unexpected and unceremonious eviction from forward positions at the onset of major war is not something to be dismissed because it is an inconvenient scenario, nor does the response require particularly imaginative solutions. It requires the expansion of existing or in-development capabilities to a capacity capable of supporting large-scale expeditionary operations by the Joint Force. Indeed, there are many commonalities between what has been discussed, and the effects of a first strike on U.S. forward positions by the PLA’s Rocket and Air Forces, namely the loss of enabling shore-based infrastructure. The key difference is that the Joint Force will not be able to rely on surging temporary forces – ISR, logistics, strike, and others – onto alternate or austere sites on the territory of allies and partners in certain scenarios.

The U.S. must prepare, today, for the possibility of a zero access environment in a western Pacific contingency to preserve military options and avoid losing a conflict before the first shots are fired. Failure to prepare may leave the United States in a situation akin to that of Rear Admiral Dewey’s fleet in 1898 when they were forced to depart from neutral Hong Kong “without a home base or reliable source of coal in wartime,” essentially to conquer or die. This time, the away team won’t be facing a decrepit Spanish fleet, but the most formidable military challenger in a generation.

Blake Herzinger (@BDHerzinger) is a civilian Indo-Pacific defense policy specialist and U.S. Navy Reserve officer. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not represent those of his civilian employer, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Elee Wakim (@EleeWakim) is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and a Presidential Management Fellow. The views expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Featured Image: Singapore (Jul. 14, 2015) – The littoral combat ship USS Fort Worth (LCS 3), top left, and the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Lassen (DDG 82), top middle, rest in port at Changi Naval Base during Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) Singapore 2015. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Jay C. Pugh/Released)