Regional Strategies Topic Week

By John Bradford

Japan’s maritime strategy is fundamentally focused on partnering with its United States ally to ensure that the Indo-Pacific sea lanes critical to its security are safe and secure. Most of the activities by its two maritime security services, the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) and Japan Coast Guard (JCG), are focused on Japan’s near seas and seek to deter aggressive actions by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), North Korea, and Russia while enabling good governance of the Japanese EEZ. Japan also deploys its forces to locations along those sea lanes, such as the Gulf of Aden and Strait of Hormuz, where Japanese shipping is under significant and direct threat. Equally critical to the strategy are the Japanese activities aimed at the relatively more safe and secure, yet still vulnerable sea lanes that pass through and near Southeast Asia. This includes enclosed seas such as the South China Sea, Java Sea, and Bay of Bengal as well as critical chokepoints such as the Straits of Malacca, Singapore, Sunda, and Lombok.

Much of this effort draws on Japan’s economic strength and Japan has been heavily invested in developing infrastructure and safety capacity alongside this region’s coastal states for more than 50 years. For the last 20 years the Japan Coast Guard has also been engaged with developing the coastal states’ maritime law enforcement capacity. In the last decade, the Japanese Ministry of Defense has become involved. It has started new capacity-building projects with regional navies and the JMSDF has been increasingly conducting military operations in the regional waters.

With all branches of Japan state power now investing in Southeast Asian maritime security, this region is cementing as a new nexus in Japan’s maritime strategy. The scope, strategic intent, and likely future development of Japan’s maritime security activities in Southeast Asia merits closer examination.

Japan’s Maritime Strategy

Japan’s well-established maritime security strategy can be broadly separated into two geographic segments, one pertaining to Japan’s home waters and the other to Indo-Pacific sea lanes. In its near seas, Japan faces significant security pressures from the north, west, and south. Aggressive contemporary military postures, territorial disputes, and war legacy issues create security concerns and constrains cooperation between Japan and its neighbors Russia, China, and the Koreas.

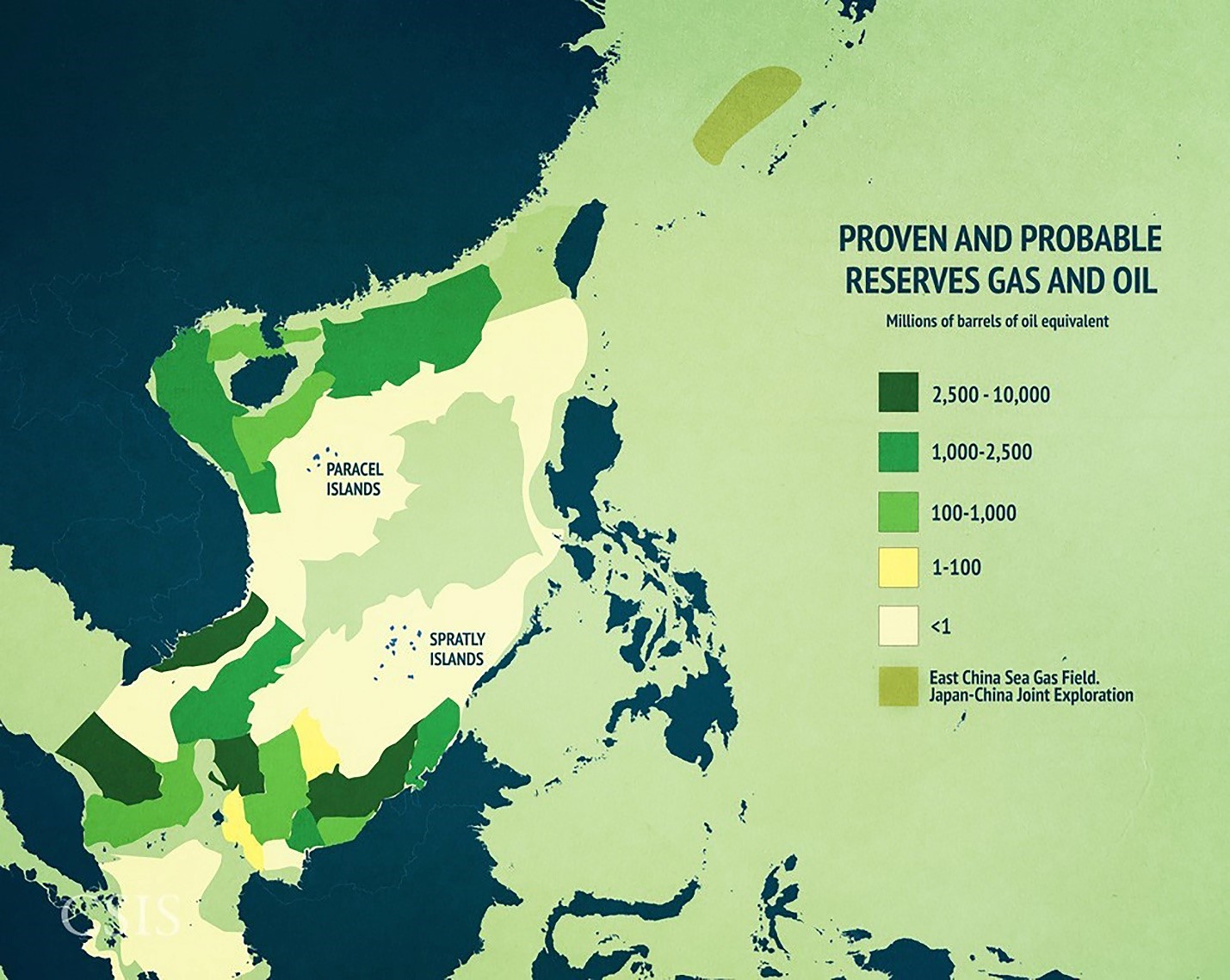

In the maritime space, the competition with the PRC is the most strained. The concentric rings of Japanese and PRC coast guard and naval forces persistently contest sovereignty, probe reactions, and seek to assert control over the waters surrounding the Senkaku (Diaoyu in Mandarin) islands.1 This situation demands significant fleet resources while the remainder of the East China Seas provides a long front for patrol and surveillance. The ballistic missile threat from North Korea and Japan’s support for the enforcement of United Nations Security Council sanctions against that state also keep the fleet busy. Above the waters approaching Japan, the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) regularly scrambles fighters in response to PRC and Russian flight operations. Given this increasingly severe situation, protecting Japan’s rights and executing its national responsibilities in the sea and airspace associated with the nation under UNCLOS have occupied the bulk of Japan’s security resources.

Although pressured in home waters, the government of Japan has long understood that its national security equally relies on the safe transit of goods along critical sea lanes. As measured in calories, Japan is reliant on imports for more than 60 percent of its food.2 Japan is also 99.7 percent, 97.5 percent, and 99.3 percent dependent on imports for crude oil, liquified natural gas (LNG), and coal, respectively. Together, these three commodities provide more than 85 percent of Japan’s energy. The LNG sources are well-diversified, but 88 percent of the crude oil comes from the Middle East, and Australia is the main supplier of coal.3 Thus, most of Japan’s energy passes along Southeast Asian sea lanes. This energy fuels Japan’s status as the world’s fourth largest exporter of products. Over $700 billion of goods leave Japan, about 99 percent of those by ship.4

Japan’s strategy to ensure the safety and security of its critical sea lanes rests on three elements: capitalizing on its alliance with the United States, deploying forces to most critical threat locations, and strengthening positive relations with increasingly capable partners along the sea routes.

In recent years, Japanese maritime strategy has cleanly nested under national campaigns to focus Japan’s foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific band that stretches along its sea lanes to Europe and Africa. Shortly after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe first assumed office in 2006, Foreign Minister Taro Aso announced the Arc of Freedom and Prosperity.5 This foreign policy complemented Japan’s existing priorities involving managing relations with immediate neighbors and strengthening the U.S. alliance with an additional emphasis on promoting democracy and increased capability with an arc of partner nations stretching from northern Europe, though the Middle East, past the Indian subcontinent, and across Southeast Asia.6 Notably, this arc aligned geographically with Japan’s main trade routes minus those across the Pacific Ocean that were already secure thanks to the U.S. alliance. Abe is also credited as the first global leader to highlight the Indo-Pacific geopolitical concept when he gave a 2007 address to the Indian Parliament entitled, “Confluence of the Two Seas.”7 The next two Prime Ministers, both also from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), continued with this prioritization. When the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) led the government from 2009-2012, Prime Ministers Hatoyama, Kan, and Noda used different branding but sustained this foreign policy approach toward the coastal states of South and Southeast Asia.8 Immediately after returning to power in 2012, Abe published an essay titled “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond.” This essay opened with:

“Peace, stability, and freedom of navigation in the Pacific Ocean are inseparable from peace, stability, and freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean. Japan, as one of the oldest sea-faring democracies in Asia, should play a greater role – alongside Australia, India, and the U.S. – in preserving the common good in both regions.”9

Southeast Asia was clearly at the heart of the diamond and it is now the central nexus of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific vision announced in 2016.10

Japan’s Maritime Forces: Operations Near Home and Far Abroad

Japan’s 1945 constitution states that “sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.” Imperial Japanese Navy veterans were re-employed by the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), a civilian law enforcement body established in 1948 that was also tasked with clearing the approximately 100,000 sea mines laid around Japan during World War II. As the Cold War progressed, the United States forged an alliance with Japan and encouraged the development of Japanese defense forces. In 1952 the first U.S.-Japan security treaty was ratified and the Maritime Guard Forces, equipped with former U.S. frigates and landing craft, were established under the MSA. In 1954, this body was detached from the MSA, redesignated as the maritime component of the new Self Defense Force (SDF), and its units were quietly dispatched to support mine countermeasure operations around the Korean Peninsula. In 1960, the current U.S.-Japan Security Treaty came into force obligating U.S. forces based in Japan to provide for the defense of Japan and the security of the region. As the Cold War progressed, the JMSDF became more capable and began working hand-in-glove with the U.S. Navy (USN) to contain Soviet units operating from Pacific ports. After the Cold War, JMSDF capability continued to grow and the United States encouraged Japan to expand the geographic scope of JMSDF operations. The MSA remained a civilian force responsible for law enforcement and maintaining the safety of Japanese waters, and its name was officially revised in English to Japan Coast Guard (JCG) in April 2000.

In the years after the Cold War, the JMSDF has been dispatched on a series of mission to enhance security around the western terminus of its Indo-Pacific sea lanes. These dispatches have all been made in coordination with the U.S. and all but one responded to immediate threats to Japanese shipping. The first JMSDF operation beyond Northeast Asia was the 1991 deployment of vessels to support the clearance of sea mines from the Arabian Sea in the wake of the First Gulf War. 10 years later, it sent a force to provide logistics support to the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan. In 2009, the new DPJ government ended the Afghanistan support mission, but established a new anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden thereby continuing the persistent presence of Japanese maritime forces in the Western Indian Ocean. Initially, the JMSDF units and their JCG augments provided anti-piracy escorts and conducted maritime surveillance without being a part of any coalition, but they coordinated closely with the United States and eventually joined the U.S.-sponsored CTF 151. In 2015 and 2020, Japan commanded CTF 151. In 2020, Japan dispatched an additional maritime force to gather intelligence and protect its ships in the approaches to the Strait of Hormuz. The government of Japan has made clear that these forces were not a part of the U.S. Operation Sentinel to guard shipping against Iranian provocations. However, it should be noted that the dispatch was made after a U.S. request, so may represent a compromise within the alliance. It can be safely assumed that the operations, including the P-3 flights originating from a Djibouti runway Japan shares with American forces, are coordinated with the U.S. 5th Fleet in a manner reminiscent to that of the initial anti-piracy deployments in 2009.

Japanese Civil Activities to Strengthen Southeast Asian Maritime Safety and Security

The sea lanes between Japan’s home waters and the dangerous sea space around the Middle East stretch for more than 5000 nautical miles. For the most part, these sea lanes pass by coastal states capable of providing the governance needed to ensure safety that is sufficient for the free flow of commerce. However, the coastal states vary widely in terms of maritime capacity, the sea lanes are far from hazard free, and Japanese business and government leaders worry about the possibility that disruptive events could quickly create a crisis. The hazards that concern Japan include the navigation challenges associated with densely trafficked chokepoints, environmental challenges such as extreme weather and oil spills, piracy, terrorism, and war risks. For the last five decades Japan has become increasingly involved in addressing these challenges by supporting coastal state capacity-building projects as a core element of its maritime security strategy.

Japan began these efforts in the late 1960s with an initial focus on assisting coastal state efforts to improve navigational safety in Southeast Asian waterways. The key milestone marking the start of these activities was the founding of the Malacca Strait Council (MSC) in 1969. This Tokyo-based organization coordinated efforts of the privately-funded Nippon Foundation with those of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Japanese Transportation Ministry, and JCG. Projects included the installation and maintenance of navigation aids, the removal of shipwrecks, the provision of oil skimming vessels, the donation of a buoy tender to Malaysia, and dredging work.11

In the 1970s the Japanese foundations and government agencies expanded their capacity-building activities to include waterways and coastal states beyond the Straits of Malacca and Singapore. These projects neatly aligned with Japan’s other Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) activities in Southeast Asia that similarly aimed to build capacity that strengthen the region’s trust in Japan and develop relationships that would help drive Japan’s economic success. When, in 1975, the grounding of the Japanese tanker Showa Maru created a massive oil spill in the Singapore Strait, Japan swiftly recognized the potential for environmental catastrophes to interrupt commerce and added environmental protection to their capacity-building portfolio.12 Under the 1977 Fukuda Doctrine, this ODA was decoupled from political objectives and Japan pledged that it would not assume a military role in Southeast Asia. When, in 1981, Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki responded to U.S. demands for Japan to assume greater burdens within the alliance by announcing the JMSDF would begin defending sea lanes up to 1000 nautical miles from Japan, it was no coincidence that the distance reached only the Bashi Channel and not into the South China Sea. Indeed, Japan remained quite concerned about memories of war and Southeast Asia sensitivities.13

In the early and mid-1990s, Japan took advantage of its improved standing in the region to take initial steps to become involved in Southeast Asia’s maritime security. For example, a subsidiary of the Nippon Foundation provided most of the seed money for the International Maritime Bureau Piracy Report Centre established in Kuala Lumpur in 1992, and the Japanese shipping industry covered significant portions of its operating costs.14 During the 1990s the JMSDF also conducted some leadership engagements under the auspices of the Western Pacific Naval Symposium and held its first navy-to-navy staff talks with Southeast Asian partners in 1997.15

The rise of regional piracy rates in the wake of the 1997 Asian Monetary Crisis catalyzed an expansion of Japan’s capacity-building efforts to include maritime law enforcement.16 Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi kickstarted this expansion at the December 1999 ASEAN +3 summit when he sought international cooperative actions against piracy by proposing the establishment of a regional “Coast Guard body,” the strengthening of state support for shipping companies, and improvement of regional coordination.17 Soon Japan was offering equipment and training, and pressing for joint patrols.18 After a series of Japanese fact-finding delegations visited the region and Tokyo-hosted several large conferences, the Japan’s ambitions were scaled back, but the expanded involvement in Southeast Asian maritime law enforcement nonetheless came quickly. In 2000 the JCG began establishing permanent overseas positions for officers to support regional coast guards (starting with the nascent Philippine Coast Guard), and in 2001 the JCG began exercising with regional coast guards (starting with the Philippines and Thailand). In 2006 Japanese diplomatic efforts culminated in the creation of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP).19

A notable aspect of Japan’s support for Southeast Asia’s maritime security has been transfer of patrol boats to regional maritime law enforcement agencies. These transfers have included used converted fishing vessels, retired Japanese patrol boats, and new construction vessels. They have been provided by private Japanese foundations, through government facilitated loans, and as direct assistance. An early example were the transfers to Indonesia and the Philippines made in the mid-2000s. As these vessels were armored, the transfers were governed by Japan’s Three Principals on Arms Exports and the receiving partners could only use them for law enforcement operations, to include anti-piracy and counterterrorism.20 Relaxations of the Three Principals in 2011 and 2014 have streamlined the policy process and in recent years Japan has expanded its programs to provide patrol vessels. To date, coast guard and maritime law enforcement agencies in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pulau, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam have received patrol vessels from Japan.

Japan Self Defense Force Operations in Southeast Asia

Civilian arms of Japan’s foreign policy apparatus have been investing in strengthening the safety and security of Southeast Asian sea lanes for more than 50 years. In contrast, the JMSDF was essentially absent in Southeast Asia until a bit over a decade ago. That is not to say it was completely missing. Its annual training cruise invariably made some goodwill port visits in the region, ships and aircraft paused to enjoy liberty and build relations while enroute to and returning home from missions in the Western Indian Ocean, it was involved in Western Pacific Naval Symposium (WPNS) activities, and it provided transportation support to peacekeeping operations in Cambodia and Timor Leste.21 However, these activities were irregular, generally small in scale, and did not involve strengthening the capabilities of neither the JMSDF nor their partners. In the most recent 10 or so years, a period that scholar Andrew Oros marks as corresponding to a Japanese “security renaissance” when a broad political consensus developed in favor of expanding Japan’s direct involvement in international security affairs, the JMSDF began deploying forces specifically to influence the security situation in Southeast Asian waters.22

The earliest JMSDF ship deployments aimed specifically to impact the Southeast Asian maritime security situation were in alignment with multilateral efforts and frameworks. In December 2004, SDF ships and aircraft were among the international forces that responded to the Indian Ocean tsunami.23 In 2005, the JMSDF participated in the inaugural WPNS at-sea exercise that was hosted by the Republic of Singapore Navy, and the Japan Ground Self Defense Force (JGSDF) officers participated in the tsunami relief workshop and high-level staff exercise portions of the U.S.-Thai exercise Cobra Gold.24 Since then, maritime exercises sponsored by multilateral organizations such as WPNS, ARF, and ADMM+ have become more frequent and the JMSDF has consistently participated, often sending the largest contingents.25 While significant from a defense diplomacy perspective, these multinational maritime exercises were often quite simple and were aimed more at confidence-building than strengthening operational capacity. Many focused on disaster response rather than more traditional security concerns.26

Japan’s National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) of 2010 was the first major Japanese policy document to state that the SDF would begin conducting capacity building missions with foreign militaries. The first operation of this new policy was the 2010 deployment of a JMSDF ship to conduct capacity-building activities in Vietnam and Cambodia as a part of the U.S. Pacific Partnership campaign. Since then, JMSDF ships have participated in Pacific Partnership annually, only missing 2011 when they were occupied with supporting domestic disaster response operations in the wake of the tsunami and earthquake. In 2012, Japan executed its first bilateral capacity-building activity in Southeast Asia, an underwater medicine seminar held with the Vietnam Navy. The second bilateral event was a February 2013 oceanography-focused seminar held at the Indonesian Navy Maritime Operations Center in Jakarta. Since then, Japan has conducted similar bilateral capacity-building activities with another eight partner nations. Of these 10 partners, all but Mongolia are South China Sea or Bay of Bengal coastal states.27 In December 2013, Japan’s first ever National Security Strategy explained the strategic intent behind these activities: “Japan will provide assistance to those coastal states alongside the sea lanes of communication and other states in enhancing their maritime law enforcement capabilities, and strengthen cooperation with partners on the sea lanes who share strategic interests with Japan.”28 In November 2016, Japanese Defense Minister Tomomi Inada delivered the Vientiane Vision at the second ASEAN-Japan Defence Ministers’ Informal Meeting. Meant to be a major defense policy statement, the Vientiane Vision outlined Japan’s priority for defense cooperation with the ASEAN states as centering on the principles of international law, especially in the field of maritime and air space; promoting maritime security through the building of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) and search and rescue (SAR) capacities, and capability growth in other security fields.29

In the last decade, the JMSDF has also expanded its naval operations in the South China Sea. Unlike the multilateral exercises and capacity-building activities previously mentioned, these activities appear to be more focused on developing JMSDF options to conduct high-end naval operations around that body of water. In that sense, the activities clearly go well beyond the militarization and geographic limitations described four decades ago in the Fukuda and Suzuki Doctrines. Since the government of Japan does not publish the locations of its ships and submarines, it is unclear exactly when these deployments began. One of the earliest activities reported by the Japanese government was a June 2011 trilateral JMSDF-USN-Royal Australian Navy (RAN) exercise in the South China Sea. Since then, reports of JMSDF exercises with other extra-regional navies in the South China Sea have become increasingly frequent. However, JMSDF operational presence in the South China Sea may date back even further. After the Japanese government reported a September 2018 unilateral ASW exercise in the South China Sea, Prime Minister Abe explained, “Japan has been performing submarine exercises in the South China Sea since 15 years ago [sic]. We did so last year and the year before that.”30 The apparent emphasis on ASW may reflect concerns that PRC submarines could interdict Japanese shipping. Some analysts, including some retired JMSDF admirals, argue that the JMSDF is also readying itself to be able to counter a potential PRC ballistic missile submarine bastion in those waters.31 Either concern would help explain the JMSDF’s emphasis on its partnerships with the Philippines and Vietnam, the nations that straddle the north section of the South China Sea, and flank the important PRC submarine base on Hainan Island.

The JMSDF’s relationship with the Philippine Navy is the most developed of its Southeast Asia partnerships. SDF officers began observing the annual U.S.-Philippines Balikatan exercise in 2012 and involvement increased such that the ‘observing’ delegation of 2018 included two destroyers and a submarine. The Philippines also hosted a JMSDF P-3 for a maritime patrol exchange that took place simultaneously with the U.S.-Philippines exercise CARAT 2015. Japanese P-3s have since visited for several additional cooperative events, and in May 2018 the JMSDF deployed a P-1 to the Philippines for a training event. Notably, before this mission, P-1s had only been deployed overseas for airshows and for a brief counter-piracy mission flying from Djibouti. In 2016, Japan’s training submarine Oyashio visited Subic Bay alongside two JMSDF destroyers and the crews took part in confidence-building activities with Filipino counterparts. This was the first JMSDF submarine port call to the Philippines in 15 years, but since that event JMSDF submarines have been frequent visitors to Subic Bay.32

In October 2018, the JGSDF’s nascent Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade (ARDB) landed amphibious assault vehicles from a USN ship onto the Philippine shores during the U.S. and Philippine exercise Kamandag. This was the first overseas deployment of the ARDB, a unit created, at least in part, to conduct defensive operations against potential foreign state aggression around Japan’s outlying islands. It was also the first deployment of Japanese armored vehicles to Southeast Asia since World War II. Although Japanese spokesmen emphasized that the training was focused on disaster response, other elements of the U.S.-Philippine joint military exercise suggest that it was structured in such a way to also have military applications.33

The Philippines is also the first, and, thus far, only, nation to acquire Japanese defense equipment. 2014 policy reforms allowed Tokyo to approve defense exports to partner militaries, and in 2017 two used JMSDF TC-90 training aircraft were delivered directly from the SDF to the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) where they were redesignated as C-90s for work as maritime patrol aircraft. Three additional TC-90s were transferred in 2018. Although offering a significant boost to the Philippine ability to develop maritime domain awareness, this new capacity offers limited military value. The C-90s are incapable of carrying weapons and do not incorporate the sort of electronic information collection and sharing system required for effective military surveillance and targeting missions. There are reports that Japan is interested in transferring P-3C aircraft, an ASW-focused aircraft capable of carrying a wide array of weapons and electronic systems, to Southeast Asian partners, but contacts in those countries have explained to the author that their preference for lower life-cycles costs would likely result in acquiring newly constructed European options.34

In August 2020, Japan’s Mitsubishi Electric Corporation concluded a contract with the Philippines’ Department of National Defense to support four air defense radars. For the Philippines, the three FPS-3 fixed radar units and one TPS-P14 mobile radar will provide it considerable new capability to detect and track missiles and aircraft. For Japan, this transfer breaks new ground in that it is the first transfers of newly-built Japanese-made defense equipment to any nation since the end of World War II. In contrast to past transfers of unarmed patrol boats and aircraft, this is the first Japanese transfer of equipment that will enable much more significant contributions to creating the kill-chains need to counter serious military threats.35

Japan has also been prioritizing the development of its defense relations with Vietnam. Japan’s first JMSDF capacity-building activity in the region was the previously mentioned 2010 dispatch of JS Kunisaki to Qui Nhon, Vietnam under the Pacific Partnership umbrella. While focused on medical treatment activities and cultural exchanges, the visit included the use of amphibious vehicles landing on a Vietnamese beach.36 The next year, Vietnam hosted the first SDF capacity-building activities in Southeast Asia that were not facilitated as part of a U.S. or multilateral event. Since then the relationship has continued to grow, though it has not yet reached a level such that it includes bilateral defense exercises or operations. In April 2016, two Japanese destroyers made the country’s first-post war port call at Cam Ranh Bay. In 2018, JS Kuroshio became the first-ever JMSDF submarine to visit Vietnam. Interactions ashore included courtesy calls and cultural exchanges.37 In 2019, JS Izumo (the helicopter carrier now slated for refit to carry F-35B fighters) and an escort visited Cam Ranh Bay and conducted goodwill exercises with a Vietnam Navy corvette.38 This decade of engagements is clearly creating a valuable partnership. In April 2020, Vietnam agreed to provide refueling services to a JMSDF P-3 returning home from a Djibouti deployment when other nations declined due to their COVID-19 precautions. The aircraft then developed mechanical issues preventing its departure. Vietnam hosted the crew for nearly two months and facilitated special arrangement or the entry of technicians and parts during the height of the pandemic.39

Annual deployments of large helicopter carriers such as Izumo for a multi-month deployment to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean provide excellent encapsulations of the varied nature of new JMSDF activities in the region. In 2016, during the first of these deployments, JS Ise was the largest ship at the multinational exercise Komodo hosted by Indonesia. Ise then transited to the South China Sea with a cadre of midshipmen from WPNS navies onboard for training while conducting a trilateral passing exercise with RAN and USN ships.40 After a goodwill visit to Manila, Ise was then the largest ship involved in the May 2016 ADMM+ Maritime Security/Counter-Terrorism Field Training Exercise that began in Brunei and concluded in Singapore. The following year, the largest ship in the JMSDF fleet, JS Izumo, made a similar deployment to Southeast Asia that included a maritime security training program for officers from ASEAN navies while the ships were in the South China Sea; hosting Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte during a port visit to Manila; calling in Sri Lank; and completed two days of exercises with ships from Australia, Canada, and the U.S. that included cross-deck exchanges and live-fire events.41 Similar deployments in 2018 (JS Kaga) and 2019 (JS Izumo) similarly blended unilateral operations in the South China Sea, exercises with the U.S. and other extra-regional navies, support for multilateral maritime security programs, and bilateral relationship-building with regional partners.42

Conclusion: Future Trajectories for Japan’s Involvement in Southeast Asian Maritime Security

The blended nature of the JMSDF capital ship deployments to Southeast Asian waters reflects its multifaceted maritime goals in the region. Japan is expanding on its decades of capacity-building initiatives in the region to include military dimensions. These activities are aimed at creating strengthened relationships with increasingly capable coastal states along Japan’s Indo-Pacific sea lanes. These naval activities are in some ways a simple progression of Japan’s longstanding policy to support the development of maritime capacity. However, this expansion reflects a loosening of Japan’s domestic policy constraints and the increased comfort that Southeast Asian partners have with hosting Japanese forces. The PRC’s increasing capabilities and assertive maritime behavior have hastened this trajectory given Japan’s heavy reliance on South China Sea sea lanes and Japan’s concerns that China’s campaign to assert sovereignty in the South China Sea is strongly linked to its campaign against Japan in the East China Sea.

Japan’s overarching strategic goal to promote the sustained safety and security of the critical Southeast Asian sea lanes has remained essentially unchanged for more than 50 years. However, Japan has incrementally expanded the range of regional security challenges that it directly addresses and agencies that it mobilizes to assist in this effort. For the last decade or so, these agencies have included the Ministry of Defense and the JMSDF. The JMSDF now regularly deploys to the South China Sea and has a record of conducting high-end warfare exercises with the U.S. and other extra-regional navies in that contested body of water. It makes major contributions to multilateral exercises in the region and has been conducting bilateral capacity-building activities with regional navies. The activities should be expected to continue to expand with the primary limiting factors being the availability of ships and other fleet resources.

To date, the bilateral engagements in Southeast Asia have been almost entirely restrained to goodwill activities, and modest projects focused on building regional partners’ constabulary capacities. However, we can expect to see Japan become more involved in assisting regional states with the military defense capabilities. The deal to send newly built and modern air defense radars to the Philippines sets an important precedent in this regard. Continued PRC maritime aggression will be an important driver, but Japan will remain concerned by other maritime threats and increasingly seek to diversify it defense relations away from reliance on the U.S.

Although Prime Minister Abe has been an important figure driving Japan’s defense engagement in Southeast Asia, his departure is unlikely to cause major adjustments to this trajectory. The domestic policymaking constraints that previously inhibited these sort of defense activities have been dismantled and there is a broad political consensus advocating for more Japanese direct involvement in regional security affairs. Most of the LDP candidates to succeed Abe as Prime Minister played a direct role in developing and implementing these policies. Others, such as former Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba, hold similar views. Even the opposition party seems comfortable with expanding SDF operations in Southeast Asia. This is not an area where they have resisted, it was on their watch that ships were first sent to Southeast Asia for disaster response and then under the Pacific Partnership umbrella.

The developments are proceeding in general alignment with a Japanese effort to foster stronger multilateral security networks and new bilateral partnerships in the face of a shift in relative power and influence that is unfavorable to its ally, the United States. With the Ministry of Defense and SDF joining the other Japanese agencies as direct participants in Southeast Asian maritime security, Southeast Asia has clearly become a new nexus in Japan’s maritime strategy. It is important for Southeast Asian states to realize that as Japan’s self-restraint relaxes, they will face bigger decisions regarding the nature and scope of the defense relations they desire with Japan.

John Bradford is a Senior Fellow in the Maritime Security Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies and the Executive Director of the Yokosuka Council on Asia Pacific Studies. Prior to entering the research sector, he spent 23 years as a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer focused on Indo-Pacific maritime dynamics.

References

1. Patalano, A., “A Gathering Storm? The Chinese ‘Attrition’ Strategy for the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands,” RUSI Newsbrief, 21, 21 Aug 2020. https://rusi.org/publication/rusi-newsbrief/chinese-attrition-strategy-senkaku

2. Hirasawa, A. “Formation of Japan’s Food Security Policy: Relations with Food Situation and Evolution of Agricultural Policies,” Norinchukin Research Institute, 1 Aug 2017, p. 16. https://www.nochuri.co.jp › english › pdf › rpt_20180731-1

3. Japan Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “2019- Understanding the Current Energy Situation in Japan,” 1 Nov 2019. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/en/category/special/article/energyissue2019_01.html#:~:text=Japan%20depends%20on%20imports%20from,)%20and%2099.3%25%20for%20coal.&text=*Figures%20in%20percentage%20may%20not,to%20100%25%20due%20to%20rounding.http://www.jpmac.or.jp/img/relation/pdf/epdf-p01-p05.pdf and The Observatory of Economic Complexity, “Japan.” https://oec.world/en/profile/country/jpn

4. Japan Maritime Center, Key Figures of Japanese Shipping 2013-2014, pp 1-4. http://www.jpmac.or.jp/img/relation/pdf/epdf-p01-p05.pdf

5. Aso, T. “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity: Japan’s Expanding Diplomatic Horizons,” Japan Institute of International Affairs Seminar, 30 Nov 2006. https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/fm/aso/speech0611.html

6. Zakowski, K., Bochorodycz B., and Socha M., Japan’s Foreign Policy Making: Central Government Reforms, Decision-Making Processes, and Diplomacy, Springer, 2017, pp. 123-4.

7. Abe S, “Confluence of the Two Seas” Parliament of the Republic of India, 22 Aug 2007. https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

8. Taniguchi, T. “Beyond ‘The Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’: Debating Universal Value in Japanese Grand Strategy,” Asia Papers Series 2010, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2010, p. 8. https://www.gmfus.org/publications/beyond-arc-freedom-and-prosperity-debating-universal-values-japanese-grand-strategy

9. Abe, S. “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond,” Project Syndicate, 27 Dec 2012. https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe

10. Watanabe, T. “Japan’s Rational for the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy,” The Sasakawa Peace Foundation, 30 Oct 2019. https://www.spf.org/iina/en/articles/watanabe_01.html

11. Kato, E. (2013, Oct 7-8). “Activities and View of the Malacca Strait Council,”” 6th Co-operation Forum, Cooperative Mechanism on Safety of Navigaton and Environment Protection in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, 7-8 Oct 2013. http://www.cm-soms.com/uploads/2/6/CF6-4.5.%20Users%20Point%20of%20View%20(By%20Malacca%20Strait%20Council).pdf and Kato, E., “Activities and Views of the Malacca Strait Council,” 8th Co-Operation Forum, 4-6 Oct 2015. http://www.cm-soms.com/uploads/2/40/CF2-2-%20Activities%20and%20Views%20of%20MSC%20(MSC).pdf

12. Daniel, J. “Tugs Battle Oil Slick,” The Straits Times, 7 Jan 1975, p. 1. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19750107-1.2.2 and Daniel, J. “Slicks are Kept off Beach,” The Straits Times, 10 Jan 1975, p. 1. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19750110-1.2.3

13. Hoshuyama N, Oral history interview, K. Murata, M. Iokibe, & A. Tanaka, Interviewers, 19 Apr 1996 and Nishiro, S., Oral history interview, K Murata, interviewer, 1995.

14. Nguyen, S. H. (2013). ASEAN-Japan Strategic Partnership in Southeast Asia: Maritime Security and Cooperation. In R. S. Soeya, Beyond 2015: ASEAN-Japan Strategic Partnership for Democracy, Peace, and Prosperity in Southeast Asia, Japan Center for International Exchange, 2013, p 222.

15. Katzenstein, P., & Okawara, N., “Japan, Asian-Pacific Security, and the Case for AnalyticalEclecticism.” International Security, 26(3), 2001, p. 152.

16. Bradford, J. “Japanese Anti-Piracy Initiatives in Southeast Asia: Policy Formulation and Coastal State Responses.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 26(3), 2004, pp. 489-90.

17. Chanda, N. “Foot in the Water.” Far Eastern Economic Review, 9 Mar 2000.

18. Takei, S., Suppression of Modern Piracy and the Role of the Navy. NIDS Security Reports, 2003, pp. 38-58.

19. Bradford, J, “Japanese Naval Cooperation in Southeast Asian Waters: Building on 50 Years of Maritime Security Capacity Building Activities,” Asian Security, 25 May 2020, pp. 13-14.

20. Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japans’ Official Development Assistance White Paper 2006. https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/white/2006/ODA2006/html/honpen/hp202040400.htm

21. Yoshihara, T. and Holmes, J., “Japan’s Emerging Maritime Strategy: Out of Sync or Out of Reach?” Comparative Strategy, 27(1), 4 Mar 2008, p. 31.

22. Oros, A., Japans Security Renaissance. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

23. Yoshihara, T. and Holmes, J., “Japan’s Emerging Maritime Strategy: Out of Sync or Out of Reach?” Comparative Strategy, 27(1), 4 Mar 2008, p. 32.

24. Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Command and Staff College. Western Pacific Naval Symposium Seminar for Officers of the Next Generation. N.d. http://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/navcol/seminars/eng_wpns_song.html; Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (n.d.). Retrieved from Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs: https://www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/imindef/press_room/…/2005/…/18may05_fs.html; and Slavin, E. (2005, May 9). Japan is New Player at Cobra Gold. Stars & Stripes. https://www.stripes.com/news/japan-is-new-player-at-cobra-gold-1.32955

25. Shoji, T., “Japan’s Security Cooperation with ASEAN: Persuit of a Status as a ‘Relevent’ Partner.” NIDS Journal of Defense and Security (16), Dec 2015, pp. 97-110.

26. Bradford, J., & Adams, G. “Beyond Bilateralism: Exercising the Maritime Security Network,” Issues & Insights, 2016, p. 6.

27. Japan Ministry of Defense, International Policy Division, Bureau of Defense Policy. “Japan’s Defense Capacity-Building Assistance.” April 2016, pp. 2, 8-10 and Japan Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2014, 2014, pp. 273-4.

28. Japan National Security Council, National Security Strategy, 17 Dec 2013, p. 17.

29. Japan Ministry of Defense. (n.d.). Vientiane Vision: Japan’s Defense Cooperation Initiative with ASEAN. https://www.mod.go.jp/e/d_act/exc/vientianevision/

30. Kato, M., “Japanese submarine conducts drill in South China Sea,” Nikkei Asian Review, Sept 17, 2018 and Kusumoto, H., “Japanese submarine trains for first time in South China Sea,” Stars & Stripes, Sept 18, 2018.

31. Leavenworth, S., “How Beijing may use the South China Sea to create a Submarine Haven,” The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Jun 2015. https://www.smh.com.au/world/how-beijing-may-use-south-china-sea-to-create-submarine-haven-20150623-ghuwzm.html

32. Johnson, J., “Japanese Submarine, Destroyers arrive in Philippines for Port Call Near Disputed South China Sea Waters,” The Japan Times, 3 Apr 2016. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/04/03/national/msdf-submarine-escort-ships-arrive-philippines-port-call-training/

33. Fuentes, F., “Japanese Amphibious Soldiers Hit the Beach in the Philippines with U.S. Marines, 7th Fleet,” USNI News, Oct 15, 2018, https://news.usni.org/2018/10/15/japanese-amphibious-soldiers-hit-beach-philippines-u-s-marines-7th-fleet

34. “Japan to Donate Patrol Aircraft to Malaysia: Report,” The Straits Times, May 6, 2017 and Panda, A “Second-Hand Japanese P-3C Orions Might Be the Right Call for Vietnam,” The Diplomat, 27 June 2016 and various privileged sources, Kuala Lumpur and Langkawi, Malaysia, March 2019.

35. Embassy of Japan in the Philippines, “Transfer of the Air Surveillance Radar Systems to the Philippines, 28 Aug 2020. https://www.ph.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/11_000001_00188.html

36. Japan Maritime Self Defense Force, “About Participation in Pacific Partnership 2010,” https://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/formal/english/operation/ppt10.html

37. Parameswaran, P., “Why Japan’s First Submarine Visit to Vietnam Matters,” The Diplomat, 29 Sept2018. https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/why-japans-first-submarine-visit-to-vietnam-matters/

38. Gady, F. “Japan’s Largest Flattop Visits Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Port,” The Diplomat, 17 Jun 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/06/japans-largest-flattop-visits-vietnams-cam-ranh-port/ and Japan Maritime Staff Office, “Goodwill Exercises with the Vietnam People’s Navy,” 17 Jun 2019. https://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/en/release/201906/20190617.pdf

39. “Japan thanks Vietnam for Assisting Military Aircraft, Crew Amid COVID-19,” Vietnam Times, 7 July 2020. https://vietnamtimes.org.vn/japan-thanks-vietnam-for-assisting-military-aircraft-crew-amid-covid-19-22052.html

40. Parameswaran, P., “US Conducts Trilateral Naval Drill With Japan, Australia After Indonesia Exercise.” The Diplomat. 21 Apr 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/04/us-conducts-trilateral-naval-drill-withjapanaustralia-after-indonesia-exercise/

41. “Australia Department of Defense, “HMAS Ballarat Completes Passage Exercise,” 17 June 2017. https://news.defence.gov.au/media/media-releases/hmas-ballarat-completes-passage-exercise

42. Japan Ministry of Defense, Indo-Pacific Deployment 2019, https://www.mod.go.jp/msdf/en/exercises/IPD19.html

Featured Image: Japanese: Maritime Self-Defense Force escort ship Atago (DDG-177) front port side. April 13, 2019 at Maizuru base (Wikimedia Commons)