By Lawrence Hajek

Losing the green water sea control challenge in the South China Sea could sideline US-led efforts in Asia. The US Coast Guard’s Deployable Specialized Forces can step up to provide strategic support for INDOPAC command.

As tensions continue to build between the United States and the People’s Republic of China/Chinese Communist Party (PRC/CCP); the United States finds itself increasing blue water naval activities in the Taiwan Strait, South China Sea, and Indo-Pacific. Often-publicized Freedom of Navigation Patrols, or FONOPS, are just one of the many tools available to ensure the rule of law at sea is maintained to counter the aggressive insurgency tactics of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), China Coast Guard (CCG), and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia in the South China Sea. China’s aggressive actions directly affect the maritime security of neighboring nations, who struggle to retain control of their sovereign Exclusive Economic Zones.

Hunter Stires, a fellow with the John B. Hattendorf Center for Maritime Historical Research at the U.S. Naval War College, describes this maritime insurgency as

“a campaign to undermine and ultimately overturn the prevailing regime of international law that governs the conduct of maritime activity in the South China Sea. The key dynamic at work is a ‘battle of legal regimes,’ a political contest of wills that manifests itself in a duel between two competing systems of authority—the U.S.-underwritten system of the free sea, versus the Chinese vision of a closed, Sinocentric, and unfree sea.”

This PRC/CCP maritime insurgency is focused on two key items within the South China Sea; firstly is enforcing unlawful maritime claims and developments of reefs and island territories and second is the use of those claimed territories as logistical launching point for the exploitation of South China Sea nations through aggressive tactics, unregulated exploitation of natural resources, and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

This type of maritime insurgency is rooted in what Christian Bueger and Timothy Edmunds describes as ‘Blue Crime’:

“…distinguished by its particular relationship with the sea and the objects of harm that require protection. These include first, crimes against mobility; second, criminal flows; and third, environmental crimes. Crimes in the first category target various forms of circulation on the sea, particularly shipping, supply chains and maritime trade. In the second category, the sea is used as a conduit for criminal activities, in particular smuggling. In the third category, crimes inflict harm on the sea itself and the resources it provides.”

Maritime insurgency plays into the CCP’s larger strategic goal for the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) adopted by Beijing in 2013, an ambitious bid to put China at the center of global trading routes. Dominance and control of the South China Sea is simply a milestone in the overall strategy. This year alone, the CCP has made headlines by passing into law the authority for the CCG to fire upon foreign vessels and destroy foreign infrastructure built on reefs claimed by the CCP.

As of 2016 $3.37 in trade passes through the region annually, further highlighting global dependence on the safe shipment of these goods to and from their intended ports. A major disruption in these transit routes would cripple America’s allies in northeast Asia, as they rely heavily on the flow of oil and commerce through South China Sea shipping lanes, including more than 80 percent of the crude oil to Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

The PRC/CCP’s use of the PLAN, CCG, and militarized fishing fleet to wage a ‘Blue Crime’ maritime insurgency within the ”green-water” of the South China Sea degrades maritime security and the overall stability of South China Sea nations. This increases these countries’ susceptibility to the PRC’s Belt Road Initiative (BRI) by way of coercion or persuasion.

To counter this Blue Crime maritime insurgency, the United States must position itself between the CCP and the South China Sea nations by establishing a Maritime Counterinsurgency (M-COIN). This type of counterinsurgency requires nimble means that disrupt the CCP’s intentions without firing a shot (for the purposes of this article, “without a shot” refers to avoiding open naval combat).

A perfect candidate to execute a low-profile/low-kinetic M-COIN strategy is the US Coast Guard’s Deployable Specialized Forces (DSF). The DSFs comprise seven various sub-capabilities but the ideal capabilities for M-COIN are the Maritime Security Response Team (MSRT) and Tactical Law Enforcement Teams (TACLET). Furthermore, the MSRT includes two critical components: the Tactical Delivery Teams (TDT) and Direct Action Section (DAS), which can be either pre-positioned within a theatre of operation or rapidly deployed for higher risk operations. The TACLETs are comprised of smaller teams called Law Enforcement Detachments (LEDET), which carry out drug interdiction, maritime intercept operations (MIO), and security force assistance/foreign internal defense missions. Both MSRTs and TACLETs have carried out a mix of well-executed joint operations with DoD counterparts to combat smuggling of drugs, weapons, money, and humans worldwide.

The counter-drug mission is a joint operation led by the Joint Interagency Task Force South (JIATF-S) which coordinates DoD, Intelligence, and USCG assets to interdict vessels suspected of illicit maritime trafficking. The United States can use JIATF-South’s Pacific counterpart, JIATF-West to oversee a Maritime-Counter Insurgency (M-COIN) mission by way of a coordinated US Navy 7th Fleet task force to support its activities. USCG DSF forces are uniquely suited for the M-COIN mission as their capabilities are purpose built to fight ‘Blue Crime’ and ensure maritime security. With the inherent ability to carry out law enforcement actions, support special operations, and provide intelligence collection, the DSF is the right choice to lead the strategic green-water sea control campaign in the South China Sea and broader INDO-PAC region.

This campaign would require three key factors to effectively counter the PRC/CCP insurgency, counter aggression in the South China Sea, and disrupt the People’s Liberation Army’s expeditionary goals. The first is expanded Indo-Pacific partnerships and alliances, next is the proper employment of USCG DSF teams, and lastly is the choice of cost-effective naval platforms to support the mission.

Through this strategy, the United States can counter the PRC’s aggressive insurgent tactics while still maintaining a low profile and reducing the odds of a kinetic naval engagement. Successfully carrying out a USCG DSF-led M-COIN operation against PRC/CCP maritime aggressions would turn the tide against further PRC expansion in the South China Sea.

The United States National Defense Strategy outlines the need to expand America’s Indo-Pacific partnerships and alliances. Cooperation and coordination with South China Sea and Indo-Pacific nation partners will ensure maritime security, maintain the rule of law at sea, and ensure that the region is not susceptible to PRC/CCP influence and control.

The South China Sea nations: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam, must band together in the interest of free and open seas for the benefits of their citizens and economies. Although some of these nations, such as Cambodia and Brunei have already succumbed to pressure from Beijing, buying heavily into the BRI and staying quiet on Chinese maritime claims, other nations such as Philippines, hang in the balance as their internal politics shift from pro-Beijing rhetoric to firm opposition of China’s illegal South China Sea actions, as Philippine citizens see little benefit from BRI.

Critical Indo-Pacific strategic arrangements such as the Visiting Forces Agreement with the Philippines are just some of the many reasons the United States should be racing towards providing some level of maritime security assurance. Nations like Taiwan have fantastic working relationships with the United States and can work as a model for empowering other South China Sea nations.

Forming bilateral and multilateral agreements similar to counter-drug trafficking agreements in the Western Hemisphere can signal a shift in how South China Sea nations can respond to the PRC insurgency. These agreements provide a host of mutually-beneficial capabilities such as embarking USCG DSF personnel onboard host nation vessels to assist in LE action or vice versa, with host nation personnel aboard US vessels to enforce international or local laws. Other benefits include patrol aircraft operations in host nation territory and extradition of suspects of international or domestic crimes.

In the fight for a ‘rule of law’ at sea, these calculated steps provide a foundation to see that vision through. DSF’s teams can seamlessly integrate within host nations’ maritime force structure to contribute to law enforcement scenarios from the most basic boater safety inspections across the spectrum to high-risk joint operations with special operations. Compared to naval forces’ focus on combat at sea, the DSF’s law enforcement mission set combines a highly operational skill set with a very low threat of escalation.

The M-COIN strategy pits the United States against a multi-tiered Blue Crime system in which Beijing uses both conventional naval assets and civilian vessels, requiring a measured response that ensures naval presence while focusing on day-to-day international maritime security. Law enforcement presence will pave a pathway for each host nation to build an appropriate and scalable maritime force with the ability to assert control over its sovereign waters.

Other existing US Coast Guard programs such as the International Maritime Officers Course, which hosts commissioned international naval officers, and the Mobile Training Branch program, which sends active duty US Coast Guard personnel to host nations in a training capacity to improve their maritime forces, compliment this capability-building strategy. This international footprint builds credibility with other regional partners that can provide support in the form of vessels and aircraft.

These partners like Taiwan, Australia, Japan, and India, can be chief enablers in this counterinsurgency strategy. An approach such as a combined maritime law enforcement task group could shake Beijing’s South China Sea strategy to its core. The international community is a key stakeholder in the M-COIN strategy to counter PLAN/CCG aggressions in the South China Sea. With host nation and international support, the United States could quickly exert some green-water sea control, while enabling local states to improve their own capabilities.

A green-water sea control mission under JIATF-West supported by a 7th Fleet Maritime Combined Maritime Force offers Task Force and Commandant Command leadership a versatile maritime response capability in the Indo-Pacfic region while maintaining a broader mission aligned with the National Security Strategy.

Coupling a very broad Federal Law Enforcement Authority and with the ability to act as a branch of the armed forces, USCG DSF are a force-multiplier on the water providing reach back to virtually all US Government inter-agency partners. DSF teams have proven themselves time and again, whether interdicting narco-subs in the Eastern Pacific, or seizing Iranian missile components or large caches of weapons in the North Arabian Sea. DSFs can seamlessly integrate with US SOF counterparts for high-risk maritime missions, or operate as self-contained security advisory teams for port facilities in remote areas, unique capabilities that bring a collaborative approach to security when compared to heavy-handed PRC bullying.

Furthermore, as a member of the US intelligence community since 2001, the USCG is charged with carrying out intelligence activities in the maritime domain, filling a unique niche within the Intelligence Community by supporting Coast Guard missions and national objectives.

Integrating US Coast Guard intelligence personnel with DSFs bridges several organizational gaps by allowing the US Coast Guard to be the primary collectors and analyzers of intelligence with the support of both JIATF-West and the larger Intelligence Community. This flat and efficient structure can drive DSF teams into continuous sea-control operations against the PLAN/CCG insurgency while maintaining a strategic advantage for the region through enhanced partnerships and performance. Integrating USCG DSF in the South China Sea is part of a comprehensive, whole of government approach to countering PLAN/CCG insurgency.

A highly successful M-COIN strategy must be fiscally sustainable. The deployment of USCG DSF teams aboard host nation or coalition naval assets empowered with bilateral and multilateral international agreements is a cost effective first step.

High-cost platforms like US Navy cruisers and destroyers are not ideal for M-COIN missions in green water areas like the South China Sea. With the time, cost, and red tape required to build large grey/white hull vessels, the US Navy and Coast Guard should look towards commissioning more adaptable platforms such as the US Navy Mk VI, US Coast Guard Fast Response Cutter, and the US Navy Littoral Combat Ship. These platforms are associated with relatively low costs of ownership and high capacity for a green-water sea control mission.

The South China Sea’s nearly 1.351 million square miles require a large quantity of vessels to assert sea-control. Furthermore, the mere size of the vessels employed can signal the intent to escalate or deescalate the situation. Using smaller, cheaper craft is not only cost-effective, but also signals a commitment to peaceful law enforcement, rather than a tendency towards armed conflict.

With a price tag of $7.5 billion per Zumwalt-class destroyer and $800 million as the target cost of the Constellation-class frigate, a fleet of Mk VI boats costing $15 million per copy is a much easier sell in the defense budget. Other platforms from coalition partners such as Australia’s Cape-Class patrol boats are already used for fisheries protection, immigration, customs, and drug law enforcement operations. The Royal Norwegian Navy’s Skjold-class corvette conducts maritime security and sea control operations while still being capable of supporting special operations forces.

A positive outcome using an M-COIN strategy in the South China Sea may not signal the end of an aggressive PRC/CCP. Ultimately, the PRC/CCP would like to see a completely expeditionary overseas military force that has logistics bases throughout the world to keep its interest protected. China is positioning itself to operate militarily on a global scale as the center of the world’s economic power. No reasonable observer wants to test this rise through open war, however, the United States and its allies must recognize the economic, political, criminal, and informational warfare the PRC/CCP is waging.

Focusing on the nations that border the South China Sea and Indo-Pacific region and ensuring their economic and political viability are not part of China’s plans for hegemony, but they are vital to the United States’ resistance to the rising global power of an authoritarian regime. Building the capacity of local nations to stand up for themselves will provide a check on Chinese ambitions locally, while signaling America’s commitment to preserving the global rule of law. The United States must look at sea-control in both blue and green water, as a long term strategy for the security of our world’s oceans so that free and open commerce may persist for generations to come, benefitting emerging nations and providing stability for all people.

Lawrence Hajek is the Director of Future Operations at Metris Global, an Arizona based defense contractor focused on Special Operations training and support. He is also the owner of Pinehawk Consulting, a consultancy focused on high tech innovation in the defense and commercial industry. He is a veteran of the US Coast Guard’s Deployable Specified Forces and member of CIMSEC.

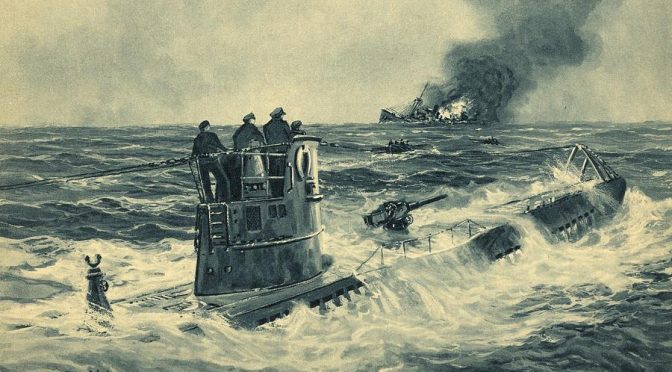

Featured image: Newly-built fishing vessels for Sansha City moored at Yazhou Central Fishing Harbor. Note the exterior hull reinforcements and mast-mounted water cannons. (Hainan Government)