Emerging Technologies Topic Week

By John Cordle and Robert Sweetman

A glimpse of what the future could hold in Human Performance Monitoring – and Improvement

This article is an exercise in “visualization,” looking at the art of the possible in combining science and technology— and changing Navy culture—to improve shipboard human performance.

The year is 2025. Onboard USS Halberg (DDG 217), my fictitious grandson, who we will call LTJG “J.T.,” is about to take the watch as Officer of the Deck. In accordance with the Navy’s Force Crew Endurance and Fatigue Management instruction, signed by the CNO in 2023, he is standing a circadian watch rotation (three hours on watch, nine hours off) which is based on decades of research demonstrating the advantages of a repeatable, stable schedule to the body’s internal clock, a policy supported (as we shall see) by modern technology that creates a holistic assessment of his performance over time.

After the deadly DDG collisions in 2017 and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on Fatigue Management and Crewing in 2021, the Navy re-examined its response to the 2017 Comprehensive Review and (finally) realized that the human is the most important part of any weapon system. This led to a fundamental shift in priorities as manpower requirements—which had long been underfunded and under-executed by as much as 15%— were made the number one priority, as GAO had recommended that “The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Office of Chief of Naval Operations uses crew requirements to project future personnel needs)” and the Department of the Navy (DON) concurred.1

Even as new technology allowed for fewer people to man the DDG Flight IIIA warships in their multi-mission role, the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act mandated 100% funding to the sea duty manpower account and ordered the Navy to measure against the full Ship’s Manning Document (SMD) requirement, instead of the funded portion. With its ability to coordinate manned and unmanned surface and airborne vehicles, which use artificial intelligence (AI) to learn about the environment and adjust tactics to an ever-changing threat, the ship is an awesome example of the implementation of the newest technology. But the heart of its warfighting capability—what makes this now fully-manned crew so formidable—is a well-honed team that is attuned to its own strengths and weaknesses thanks to human factors science and technology.

The first evidence of this is in the crew makeup. The Agile Manpower Model (AMM)2 uses AI to track and continually recalculate requirements. Gone are the days of manual calculations on a 3-year rotation by ship class; this has been replaced by an increasingly agile system that uses artificial intelligence and ever-adapting, comprehensive workload calculations, as well as a four-section Condition III watch rotation instead of the three-section model that had been used (with no real scientific basis) for decades.

AMM does not exist, but given advances in AI and the complexity of the manpower management system, it is probably just a matter of time until it does.

This approach was formally adopted in 2022 as OPNAV policy, via change to OPNAVINST 1000.16, as a necessary foundation for the unique combination of work and watch that a Navy crew needs to maintain the ship, adding a formal requirement for eight hours of protected sleep time; this despite the fact that it resulted in a slight increase in the cost (less than ten percent) of manpower. Human factors research (including a 2008 study that showed a positive correlation between manning levels and lower mishap rates)3 tipped the scales in favor of the idea that it was in fact “worth it” to man ships to the calculated requirement. In addition, improvements in technology and a focused manpower analysis showed that the idea of underfunding manpower (previously funded at only 95% and manned to 95% of that) was not conducive to optimal performance and, in fact, not cost effective when balanced across the lifecycle maintenance cost of the ship; so in 2024 the Navy decided to leverage savings in other programs to fully fund the manpower account.

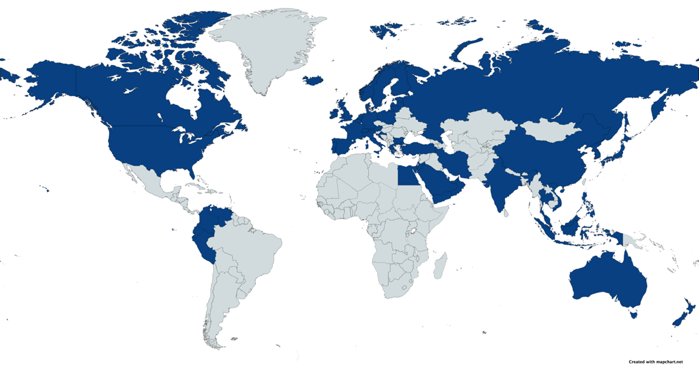

It was only through an intense collaboration of Navy research centers, including the Naval Health Research Laboratory, the Naval Postgraduate School, the Center for Naval Analysis, and others that science eventually carried the day. The Expanded SURFMEX model was a big help, matching sailor experience to fleet needs and enhancing the detailing process.4 Lots of barriers had to come down to make that happen, including making human physiology research a funded program of record instead of an ad-hoc set of independent programs, but the resulting manpower modeling software, combined with AI protocols that inject real time data from the Fleet, made this process possible.

While there have been great strides in planning, executing, and funding an improved manpower and manning process, much has been done to improve the command’s awareness of the well-being and performance of the individual crew members and teams as well. Warrior Toughness training, implemented along with the Expanded Operational Stress Control program way back in 2020, uses science to teach skills such as mindfulness, mediation, nutritional science, and exercise that have all combined to make the sailors of 2025 tougher and more resilient upon arrival, and build on that toughness throughout their career. The initiative to add Deployed Resiliency Counselors and a Chaplain to each deployed ship has paid off, as has the Behavioral Health Technician program that gives Independent Duty Corpsmen the ability to assess crew readiness and stress levels and get them assistance—before they become unplanned losses.

Other psychology and physiology-based programs such as the Command Resilience Team, the Human Factors Council, and the availability of remote psychological counseling via unclassified video teleconference have expanded the level of mental health and resilience support to those on the front lines. All of these are examples of what is special about the human factors field, where technology and knowledge combine to provide increased awareness of the human condition – and how to improve it.

There are new shipboard technologies as well. As J.T. heads to watch, he takes off the colored and lighted glasses that he put on when he awoke, designed to complement the body’s natural endocrine response that occurs during the transition from sleep to wakefulness in a process called “circadian entrainment”. He has another pair of glasses that he wears before going to bed to minimize the negative effects of blue light.5 The rack he slept in was not that of his father and grandfather— it has been replaced by the Advanced Rest and Recovery Integrated System (ARRIS). This was his safe place to retreat and recover from the stresses of the workday.6 In 2023, after the GAO report, and a series of research efforts by the Naval Postgraduate School,7 ARRIS were mandated to curb the fatigue epidemic in the Navy.

ARRIS does not exist, but it could. This would represent a new “human-factors centered” approach to a complete makeover of the Navy rack, turning it into a temperature and noise controlled environment. It includes a mattress tailored to individual preference, a full spectrum LED light to facilitate sleep and wakefulness using the optimal light wavelengths, and a set of noise reducing headphones that are also tuned to provide the sailor with a choice of white noise, natural sounds, or music as he falls asleep, bring him back to wakefulness with a gradual noise increase, and sound any ship alarm or emergency announcement that may occur during his protected sleep period. It also includes a passive heart and temperature monitor that (much like his computerized watch does at home) records his sleep quality and any disturbances that might impede his performance during his next work/watch period.

Having consumed a cup of coffee (energy drinks are generally frowned upon unless recommended by the Personal Performance Profile, PPP), another notional program that could provide a comprehensive look at each sailor’s daily alertness and fatigue levels. He checks in at the Physical Readiness Kiosk and gets a readout on his fatigue and performance level. J.T. completes a short self-assessment, where he rates his alertness level as a 6 out of 7, knowing that he fell short of the required eight hours of sleep due to an equipment casualty in his division that required overtime and supervision.

The Navy has monitored the temperatures and pressures of its fluid systems, and the voltage and current of its electrical ones, for literally centuries; the idea of doing the same for its people was a long time coming. To assess his alertness, J.T. then looks into the eyepiece of a Psychomotor Vigilance Self-Test (PVT) machine, pressing the mouse with each flash of light, speaking into the voice machine, and after three minutes is cleared, by a series of proven technologies leveraged together, to take the watch.

The PVT is used in various forms throughout industry; for example, on the International Space Station a Reaction Self-Test provides crewmembers with feedback on neurobehavioral changes in vigilant attention, state stability, and impulsivity. It helps crewmembers objectively identify when their performance capability is degraded by various fatigue-related conditions that can occur as a result of ISS operations and time in space (e.g., acute and chronic sleep restriction, slam shifts, extravehicular activity, and residual sedation from sleep medications).

Lessons learned (and applied) from past incidents (e.g., the bombing of the USS Cole, and collisions involving USS Fitzgerald, USS John S. McCain, and other near misses) have shown the need not just for toughness—the ability to recognize, analyze, and mitigate stress though mental and physical readiness—but also for resilience, since when a missile or a mine puts a hole in the ship, the first minutes—and the next 48 to 72 hours—will test the mettle of the entire crew. During these crises the crew (including the Captain) start at whatever level of personal readiness—or fatigue—that they had when the water started coming in.

J.T. remembers reading the GAO Report from 2021 where one of his (then) peers was quoted as seeing “fellow officers taking the watch in a state of senselessness driven by fatigue, unnoticed by shipboard leaders who looked the other way and ignored crew endurance principles.” My, how times (and culture) have changed!

At the end of his three-hour watch, J.T. downloads his actigraph from the motion detecting “wearable” that he wears at all times in the form of either a ring or a watch, so that his information can enter the continuous monitoring data feedback stream under the Crew Readiness, Endurance, and Watch standing (CREW).8

CREW is a pilot program to “create a decision support tool so that you can understand how fatigued people are and how much sleep they are or are not getting,” explained Dr. Rachel Markwald, a sleep physiologist from NHRC. “We can then determine how those fatigue levels correspond with the health of the individual so that we can provide a way or course of action to offset some of the risks that come with fatigue and poor health.” The long-term goal of CREW is to aid command leadership in making educated decisions about a sailor’s sleep pattern and/or their level of fatigue, capturing this data and combining it with the rest of the crew to place a real-time picture of the crew’s readiness at the CO’s fingertips. Each sailor’s data is secure, restricted from being used for any punitive measure, and and is not tied to him personally, but is available as a means of monitoring his own watch standing and work performance.

A huge part of the culture of readiness is the idea that one’s own psychological and physiological readiness relies heavily on the concept of personal responsibility.

Going over his past 24 hours and noting any deviations or issues, J.T. remembers that, in addition to the next watch cycle, he has to man the boat deck for an underway replenishment, one of the evolutions that is tagged for an Individual Risk Assessment. Looking ahead at a Fatigue Avoidance Scheduling Tool (FAST)9 printout of the next 24 hours, J.T. sees that in order to be at peak performance for the evolution that follows his next watch, he needs to take a 45-90 minute nap during the next nine hours. He programs that into his rack display, a monitor that shows his schedule for the next 24 hours so that anyone entering his stateroom will know that he is in a “protected sleep” period (if they did not see the red light outside the door, indicating such). J.T. calls it the “NORP” light, short for “Naval Officer Rest Period”. He learned that from his dad.

In the end, J.T. rests easy, knowing that he has done his part to leverage the science and technology of Human Factors to maximize his own readiness, and by extension , the performance of his team and the safety of the crew that was able to sleep soundly while he had the watch. During his Protected Sleep Period (PSP) J.T. retires to his ARRIS. The Navy had acknowledged fatigue as a major contributor to errors in judgement, mental health and operational lethargy. J.T. enters his ARRIS to begin his breathing exercises and relaxation techniques. He knows from his training that the stressors of managing the ship are carried with him in the form of nor-adrenaline as he transitions to sleep. If he wants to have restful sleep, he needs to trigger a physiological change in his brain first. Much of this knowledge was provided during pipeline training and periodic updates and under the Crew Endurance and Fatigue Management program, a Navy- wide initiative that was expanded in response to the 2021 GAO report.

In this version of the future, the implementation of human factors technology and fatigue management/crew endurance expertise, along with the combination of science, education, and technology—and finally, culture change—has been a game changer. Since the program’s inception, satisfaction at work has shot up dramatically, along with retention and operational performance scores. Reductions in mishaps and unplanned losses, combined with the savings from maintenance by fully-manned and less fatigued crews, has more than paid for the cost of research and development as well as the extra manpower that it justified. The Navy has (finally) made the decision to put sailors first and the results have been astounding. Granddad would be proud.

Dr. John Cordle is a retired Navy Captain who commanded two warships, USS Oscar Austin and USS San Jacinto, and was recognized with the 2010 Navy League Award for Inspirational Leadership, the Navy Bureau of Medicine Epictetus Award for Innovative Leadership, and the 2019 American Society of Engineers Solberg Award for his contribution to Navy Crew Endurance. This article is a figment of his active imagination built upon scientific research as it exists today – and as it could be.

Robert Sweetman is a former US Navy SEAL who served for eight years before being medically retired. He completed two tours at SEAL Team Seven, and one as an instructor at Naval Special Warfare Advanced Training Command. After retiring and following the suicide of a SEAL teammate, Mr. Sweetman continued his education at the University of California where he focused on sleep science, the link between sleep health and mental health, and designing technology to help with that problem.

Endnotes

[1] GAO 21-366, Actions Required to Address Crew Fatigue and Manning, May 2021.

[2] AMM is a capability that does not yet exist, but it could, using existing technology.

[3] Lazaretti, Patrick and Shattuck, Nita, HSI IN THE USN FRIGATE COMMUNITY: OPERATIONAL READINESS AND SAFETY AS A FUNCTION OF MANNING LEVELS, NPS Thesis, December 2008.

[4] Eckstein, Megan, “SWO Boss: Pilot Programs for Training, Manning Will Lead to More Experienced Fleet,” USNI News, 13 January 2021.

[5] Roza, David, Navy submariners are testing out their own version of ‘birth control glasses’ Make the Silent Service well-rested again. Task and Purpose, May 17, 2021.

[6] ARRIS is another capability that does not exist, but it could, using existing technology.

[7] Matsangas, Panagiotis Lewis Shattuck, Nita, Habitability in Berthing Compartments and Well-Being of Sailors Working on U.S. Navy Surface Ships, NPS Calhoun, May 2021.

[8] Harkins, Gina, “Why 300 Sailors and Marines Deployed on an Amphibious Ship with Smart Rings,” Military.com, 14 Apr 2021.

[9] FAST is one of many fatigue modeling tools used by industry to predict levels of performance degradation based on fatigue.

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (Aug. 10, 2021) Aviation Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class Armando Herrera, a native of Albuquerque, New Mexico, assigned to the “Argonauts” of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 147, inspects an F-35C Lightning II on the flight deck of Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Tyler Wheaton)