By Jan Stockbruegger and Christian Bueger

Great power competition with China and Russia dominates debates in Washington. Few analysts therefore paid attention when U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken joined Russian President Vladimir Putin and other leaders at the UN Security Council for a high-level debate on “Enhancing Maritime Security — A Case for International Cooperation” (China was represented by its UN ambassador). As expected, disagreements over basic maritime rules and norms dominated the debate. While the United States criticized Russia and China for unlawfully restricting freedom of navigation, China accused the United States of escalating conflict in the South China Sea. Yet the debate also demonstrated that the leading states share a common view on other maritime threats. The United States agreed with China and Russia not only that piracy, smuggling, and climate change undermine stability at sea, but also that states need to work closely together to address these threats and protect global maritime trade. What does this consensus suggest for U.S. strategy?

We argue that the United States should build on the consensus reached during the UN Security Council debate to enhance global maritime security, working multilaterally with China, Russia, and other states to address criminal and environmental threats at sea. The United States has traditionally protected trade routes and freedom of navigation. Securing the maritime commons is also part of the 2020 Tri-Service Maritime Strategy to maintain order at sea. Yet the U.S. Navy cannot secure the world’s oceans without the support of other states, including China and Russia. Certainly, little agreement can be expected with China and Russia on maritime disputes or their use of gray zone tactics to undermine international rules. However, China and Russia depend on seaborne trade, and they are keen to fight piracy and other threats to shipping and stability at sea. Strengthening collaboration with China and Russia on diplomatic and technical levels will therefore be vital to protect global maritime trade.

The case of maritime security has broader implications for U.S. strategy. The United States needs to defend the rules-based order against China and Russia, but it also needs to work with its adversaries to address transnational challenges such as climate change and pandemics. The maritime security case demonstrates that this balancing act is possible. The United States can – and must – both compete and cooperate with its adversaries to secure the global commons. Below we draw on the Security Council debate to analyze the maritime security landscape. We identify the joint interests of China, Russia, and the United States in protecting maritime trade, and we show how the United States can cooperate with its adversaries to ensure safety and security at sea.

Maritime competition is back

One of the reasons for the new urgency of maritime matters is the rise of maritime great power competition and the proliferation of gray zone tactics and attacks at sea. China’s growing naval and anti-access/area denial capabilities threaten U.S. dominance in the Western Pacific, but Iran and Russia have also increased their military operations at sea. China, Russia, and Iran have so far refrained from conducting aggressive maritime operations that could escalate conflict with the U.S. Navy. However, they increasingly conduct covert operations and deploy civilian or irregular forces – such as fishing vessels, coast guards, and militias – to intimidate other states and harass U.S. and allied forces at sea.

An incident that is paradigmatic for this new trend is the drone attack on the Israeli owned oil tanker MV Mercer Street in the Gulf of Oman only days before the debate. The attack, in which two sailors were killed, was the latest in a series of maritime incidents in the shadow war between Israel and Iran. An Iranian vessel was hit by a mine in the Red Sea in April 2021, for instance, and the United States believes that Iran’s Revolutionary Guards were behind attacks on four tankers in the Persian Gulf in 2019.

Yet China and Russia have also used gray zone tactics to secure contested waters. China has built military outposts in the South China Sea, and it regularly deploys its coast guard and maritime militias to protect Chinese fishing vessels in disputed waters. China’s maritime forces have harassed Filipino and Vietnamese fishing vessels, as well as the USNS Impeccable, a surveillance vessel operated by the U.S. Navy. Russia has deployed its coast guard to secure waters around the Crimean Peninsula, which it annexed from Ukraine in 2014. In 2018, the Russian Coast Guard captured three Ukrainian Navy vessels in the Sea of Azov.

China’s, Russia’s, and Iran’s gray zone tactics threaten vital U.S. and global interests in the maritime domain. U.S. Secretary of State Blinken therefore warned that “Conflict in the South China Sea or in any ocean would have serious global consequences for security and for commerce,” and that “States are (…) provocatively and unlawfully advancing their interests in the Persian Gulf and the Black Sea.” Russia largely ignored these accusations, but China responded angrily. China not only claimed that the “Security Council is not the right place to discuss the issue of the South China Sea,” but it also accused the United States of undermining “peace and stability in the South China Sea.”

Piracy is a major concern, but other crimes matter too

While China and Russia contest freedom of navigation, piracy remains a bigger threat to global shipping. From 2005 to 2012, Somali pirates attacked nearly 1,000 vessels in the Gulf of Aden and Western Indian Ocean. The World Bank estimated that piracy off Somalia cost the global economy $18 billion annually. Somali piracy has since been eliminated, but piracy remains a major threat in Southeast Asia and West Africa. According to the ICC International Maritime Bureau, an industry body, 195 ships were attacked by pirates worldwide in 2020.Last year, pirates kidnapped 130 seamen in the Gulf of Guinea, which is the world’s epicenter for maritime kidnappings.

Piracy is part of the larger problem of “blue crime,” which also includes illicit migration, maritime smuggling, and other criminal activities at sea. Human trafficking is a major problem in the Mediterranean, for example, where hundreds of migrants have drowned over the last few years. Smuggling of narcotics fuels corruption and drug abuse and led to increased rates of addiction, HIV/AIDS infection, and domestic violence in coastal communities in the Indian Ocean and other regions. Additionally, the smuggling of small arms and light weapons, which fuel conflict from Afghanistan to Somalia, often relies on maritime routes. A number of other illicit cargos are trafficked at sea, including counterfeit products, antiquities, wildlife, hardwood timber, and waste. Armed groups such as al-Shababa sometimes tax maritime smuggling activities to fund their operations.

In contrast to gray zone tactics, there is broad consensus among leading states that blue crime is a major threat to stability at sea. Ambassador Dai Bing, China’s representative at the UN Security Council, noted that “Criminal activities such as piracy, armed robbery, human and drug trafficking at sea, and maritime weapon smuggling are rampant, all of which have further destabilized relevant regions.” U.S. Secretary of State Blinken agrees: “Non-state actors also pose serious risk to maritime safety and security, from pirates and illicit maritime traffickers in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, to pirates and armed robbers in the Gulf of Guinea, to drug traffickers in the Caribbean Sea and the Eastern Pacific.”

The environmental security agenda has arrived at sea

The emphasis on blue crime is not surprising given the centrality of piracy and trafficking to the maritime security agenda. Yet the degree to which Security Council members emphasized environmental challenges was noteworthy. Two issues featured prominently in the Security Council debate: illegal fishing and climate change. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing is perhaps the most prevalent environmental crime at sea. It includes not only fishing in the waters of a state without its permission, but also fishing in marine protected areas and other fishing practices that are prohibited under national laws or international conventions. Interpol has estimated that up to USD 23.5 billion is lost to illegal fishing each year. Illegal fishing also leads to overfishing and threatens the livelihoods of coastal communities. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi therefore urged council members to “take joint steps against overfishing and marine poaching.”

Analysts also increasingly worry about the impact of climate change on the marine environment and coastal economies. The warming of the oceans, for instance, will weaken ecosystems and alter the abundance, diversity, and distribution of marine species. Furthermore, climate change increases the risk of flooding and other natural disasters, and threatens coastal ports, infrastructures, and communities. Other threats to the marine environment include pollution and oil spills from ships (e.g. the 2020 Wakashio oil spill) and offshore petroleum operations (e.g. the 2020 Deepwater Horizon oil spill). Vietnam warned the Security Council that “climate change and sea level rise and pollution of the marine environment, especially by plastic debris and degradation of the marine ecosystem, have caused serious and long-term consequences.”

Cooperation is the Strategy

No state, not even the United States, is strong enough to protect the world’s oceans alone. The oceans cover 70 percent of the earth’s surface. Every day, thousands of vessels pass through contested waters, and maritime smuggling, illegal fishing, and rising sea levels threaten coastal communities and maritime operations around the world. These threats are transnational. Pirates attack vessels in international waters, smugglers operate across national jurisdictions, and oil spills and illegal fishing operations often take place in internationally recognized protected areas. Securing the world’s oceans therefore requires states to cooperate and build international maritime infrastructure. This includes coast guard and maritime patrol vessels, communication and surveillance networks, and systems to manage marine resources and respond to accidents and environmental disasters at sea.

The United States has long led international efforts to enhance safety and security at sea. The United States initiated the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, for example, and it also facilitated the adaptation of the 2004 International Ship and Port Facility Security Code at the International Maritime Organization. In West Africa and Southeast Asia, the United States helps regional states strengthen their maritime capacities and protect their waters against piracy and illicit fishing and trafficking operations.

Yet China and Russia have also joined international efforts to protect maritime trade. They have participated in the Contact Group on Somali piracy and deployed naval forces to protect international shipping in the Gulf of Aden. Moreover, China is a member of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAPP), while Russia has participated in debates on maritime security at the ASEAN Regional Forum.

During the Security Council debate, China promised “to deepen pragmatic cooperation in combating piracy and maritime law enforcement in our joint efforts to achieve peace and tranquility in the oceans.” And Russian President Vladimir Putin not only reaffirmed Russia’s commitment “to the common task of countering crime at sea in all its forms,” but he also proposed the creation of a “special structure within the UN that would directly address problems related to combatting maritime crime in various regions.”

Beyond competition

The United States should take Russia’s and China’s offers seriously and work with its adversaries to protect the maritime commons. China and Russia will not support efforts to address maritime disputes, gray zone tactics, or illegal fishing in contested waters. Yet they are interested in working with the United States and other states to tackle piracy and maritime crime, and perhaps also to address environmental threats such as climate change and pollution.

Maritime security cooperation with China and Russia can be difficult. China was initially reluctant to share information and coordinate closely with U.S.-led counter-piracy efforts in the Gulf of Aden. The United States should therefore follow up on Russia’s proposal at the UN Security Council and establish a high-level political framework for maritime security operations. The United States could, for example, help construct a new technocratic mechanism at the UN to facilitate information sharing and the exchange of best practices in maritime governance and capacity building. The organization’s mandate would be limited to non-controversial issues such as piracy, trafficking, pollution, and climate change. China might agree to discussing maritime security in the Persian Gulf, where most of its oil originates; but illegal fishing and maritime disputes in the South China Sea would need to be excluded to ensure its support for the mechanism. International organizations, civil society, and industry groups should also be included to reinforce the technocratic and problem-driven nature of the initiative. The UN mechanism would complement ongoing regional efforts by providing a forum for global coordination and helping to form a broad consensus on maritime security governance across regions.

Critics might argue that China and Russia will exploit maritime security cooperation to project naval power and increase their geopolitical influence. China, for example, used counter-piracy operations to practice forward deployment and establish its first overseas naval base in Djibouti. China and Russia are also trying to dominate international organizations and undermine U.S. interests by supporting authoritarian regimes. Moreover, critics might argue that the proposed mechanism does not address China’s and Russia’s efforts to undermine the rule of law at sea, which are the greatest threat to order and stability on the world’s oceans.

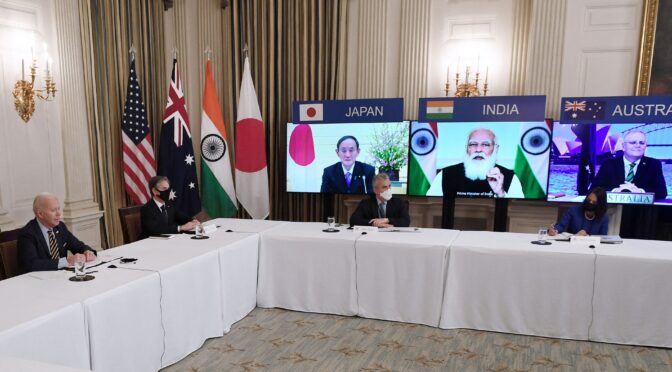

These counterarguments are valid, but they ignore the fact that China and Russia are too powerful and important to be excluded from global maritime governance. China is already the largest investor and trading nation in Africa and Southeast Asia, and Russia has increased its global influence in recent years. Moreover, China’s and Russia’s large navies can help protect dangerous shipping lanes and support coastal management and maritime capacity building activities. Working with China and Russia on countering maritime crime does not prevent the United States from defending its interests and protecting global maritime rules and norms. The United States can continue its freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea, for example, and mobilize like-minded nations through initiatives such as the Quad or the G7.

Finally, facilitating global maritime security cooperation under U.S. leadership with support from like-minded states, including the EU and India, would legitimize and help stabilize international order. It would demonstrate that U.S.-leadership is not exclusively directed against China or Russia, or about dominance. Instead, the United States would show that it takes seriously the concerns and problems of other nations, and that it is prepared to work with its adversaries to provide global public goods.

The maritime security case shows that the Biden administration needs to move beyond great power competition as its guide to foreign policy. Challenging threats to the rules-based order, no matter where they originate, is vitally important; but the United States also must cooperate with its adversaries, especially China and Russia, to secure the global commons and tackle other transnational threats, such as climate change and global pandemics.

Jan Stockbruegger is a Dean’s Faculty Fellow at Brown University’s Department of Political Science.

Christian Bueger is a Professor of International Relations at Copenhagen University and the Director of SafeSeas.

Featured image: An oil tanker is on fire in the sea of Oman, Thursday, June 13, 2019. Two oil tankers near the strategic Strait of Hormuz were reportedly attacked on Thursday, an assault that left one ablaze and adrift as sailors were evacuated from both vessels and the U.S. Navy rushed to assist amid heightened tensions between Washington and Tehran. (Credit: AP Photo/ISNA)