By Salvatore R. Mercogliano, Ph.D.

To say that the nation’s sealift resources are in distress is an understatement. One only needs to examine some of the most recent articles on this subject: “Sealift is America’s Achilles Heel in the Age of Great Power Competition”; “The US Army is preparing to fight in Europe, but can it even get there?”; “Report: U.S. Sealift Lacks Personnel, Hulls, National Strategy”; Can the US Save Its Sealift Fleet?”; and “The Next Administration Will Need to Fix Military Sealift.” If the United States finds itself engaged in peer-to-peer competition and conflict, as it has in the past during the First World War, the Second World War, and during the Cold War, it will find itself in a position that it has not been in for over a century; of a nation lacking a dedicated sealift force and a merchant marine only a fraction of a percent necessary to carry its own commerce.

Today, the Naval Fleet Auxiliary Force provides the sole underway replenishment for the U.S Navy. The Afloat Prepositioning Force, which once included three squadrons, has been reduced to two. The surge sealift fleet has been similarly cut down from 61 to 54 ships, but still below the readiness threshold to be able to transport 10 million square feet of cargo to the combatant commanders. Finally, the U.S. merchant marine is down to just 180 ships. All of this means that should the United States become engaged in another peer-to-peer conflict, they may lack the requisite sealift, merchant marine, and maritime industrial base to support the Department of Defense. Current plans include a sealift recapitalization scheme that provided funds for two used ships last year, and five more this year, but none have yet to be purchased.

The current situation is unsustainable. An examination of the past can provide some alternatives and solutions to the current dilemma the United States finds itself in.

Peer-to-Peer Conflict #1 – The First World War

On February 5, 1917, with nations engulfed in a world war, President Woodrow Wilson issued the following proclamation regarding the situation:

“[I] do hereby declare and proclaim that I have found that there exists a national emergency arising from the insufficiency of maritime tonnage to carry the products of the farms, forests, mines and manufacturing industries of the United States, to their consumer abroad and within the United States.”

The state of affairs identified by the President, which is similar to that of today, stemmed from the fact that prior to the summer of 1914, the vast majority of American imports and exports were carried by foreign merchant ships, while the U.S. merchant marine was largely focused on coastal trade due to cabotage laws. When the German fleet sought refuge in ports around the world, and European merchant ships were diverted to carry war matériel, American goods piled up on the docks, another situation akin to today. Eventually, demand for products led to massive spikes in prices, with a ton of cotton going from $0.35 to $6.10. Even though the United States possessed the third largest Navy and merchant marine in the world, they proved ill-prepared for war.

As the conflagration progressed into its third year, the United States realized it needed to make itself less reliant on foreign fleets. The Naval and Shipping Acts of 1916 aimed to create a Navy and merchant marine sufficient to challenge either Great Britain or Germany. This was the backdrop to when Germany decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare on February 1, 1917. This new maritime offensive found American ships shifted from the coastal trade, such as SS Vigilancia, to the international trade and hence targets for German U-boats. In the span of two months, ten U.S. ships were lost and 64 crewmembers killed, leading Wilson to ask for a declaration of war against Germany. As the nation debated entry in the war, Rear Admiral William S. Sims arrived in England and learned that German U-boats were achieving their goal of sinking 600,000 tons of ships per month, and even sunk in excess of 800,000 tons in one particularly hard month. Additionally, the amount of food on hand to feed the population was measured in weeks, indicating a dire predicament for the Allies.

Sims’ assessment of the situation required several immediate objectives: suppress the U-boats, increase the flow of goods and imports to Europe, and transport as quickly as possible an American military presence until the American Expeditionary Force could be fully trained, equipped, and shipped in early 1918. To meet this objective, the sealift forces available to the War and Navy departments was limited. The Army Transport Service (ATS) was concentrated in the Pacific and providing transport of troops to American possessions in the Philippines, Hawaii, and the Panama Canal Zone. The Navy Auxiliary Force provided fuel support to the fleet by delivering coal to American overseas bases.

To meet the sealift goals for the United States, the head of the U.S. Shipping Board, Edward Hurley, initiated a series of five steps. The first act in Hurley’s plan involved the requisitioning of 431 merchant ships under construction in American yards, and where nearly half of them were under contract for the Allies to replace ships sunk by German U-Boats. This was possible due to a robust maritime infrastructure in the nation and its expansion as a result of the war. Next, the Shipping Board requisitioned all U.S. flagged ships over 2,500 deadweight tons, thereby nationalizing the U.S. merchant marine. To expand the fleet, the German and Austrian ships interned in American ports since the start of the war were seized for modification into troopships and cargo vessels. The fourth pillar of Hurley’s strategy was to work with allies and neutrals to charter available tonnage, seek German and Austrian vessels in their waters, and even use the Right of Angary to seize all neutral Dutch vessels in American ports in March 1918, due to the desperate need of tonnage.

The final and longest-lasting element was a massive 3,282 ship construction program that aimed to provide 15 million tons of shipping. One of the key tenets of this effort was to incorporate several new technologies into the vessels, including pre-fabrication to accelerate construction and the use of oil as the primary fuel. This power source, which was more energy efficient compared to other sources, allowed for it to be carried in double bottoms thereby increasing both range and cargo capacity. This permitted the ships to compete against British merchant vessels powered largely by coal, but dependent on overseas bases for replenishment.

The collapse of the Central Powers in the fall of 1918 curtailed the full program, but the U.S. merchant marine had grown from 2 million gross tons to 12 million by 1920, while the British had restored their fleet back to 20 million tons. Even with this expansion, the U.S. was dependent on Allied merchant fleets to transport over 55 percent of the AEF personnel.

With the end of the war, the United States assessed its maritime capabilities. Both the Army and Navy modernized their sealift forces with the ATS taking some of the German interned liners and newly built domestic troopships. The new Naval Transportation Service followed similar lines, but retained all its military crews, purging the merchant mariners who had joined prior to the war. While the Navy would eventually curtail its capital ship construction under the Washington Treaty of 1922, the expansion of the American merchant marine fell under the first national maritime strategy, the Merchant Marine Act of 1920.

This piece of legislation not only reaffirmed the protected coastal trade for American-owned, -built, -crewed, and -operated ships, but also aimed to ensure that U.S. ships were active on key international trade routes, and that any excess ships from the Shipping Board program were retained in a reserve status for potential commercial and military use in the future. The hope was that America’s Navy would provide a bulwark against potential aggression, with U.S. ships more of a presence on the high seas, both military and civilian. But the Great Depression would have a massive impact on global trade, curtailing not merely the movement of goods, but the construction and operation of ships, and leading to the next major conflict.

Peer-to-Peer Conflict #2 – The Second World War

As in the previous world war, the U.S. entered this conflict with most of its military centered in the continental United States, with some elements forward deployed. The U.S. Navy and America’s merchant marine were the second largest in the world, behind the British, but unlike the First World War, they were much better prepared for a peer-to-peer confrontation. The passage of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 and the Navy Act of 1940 put in motion the construction of the fleet to transport the Arsenal of Democracy, and the Navy to ensure the control of sea lines of communication.

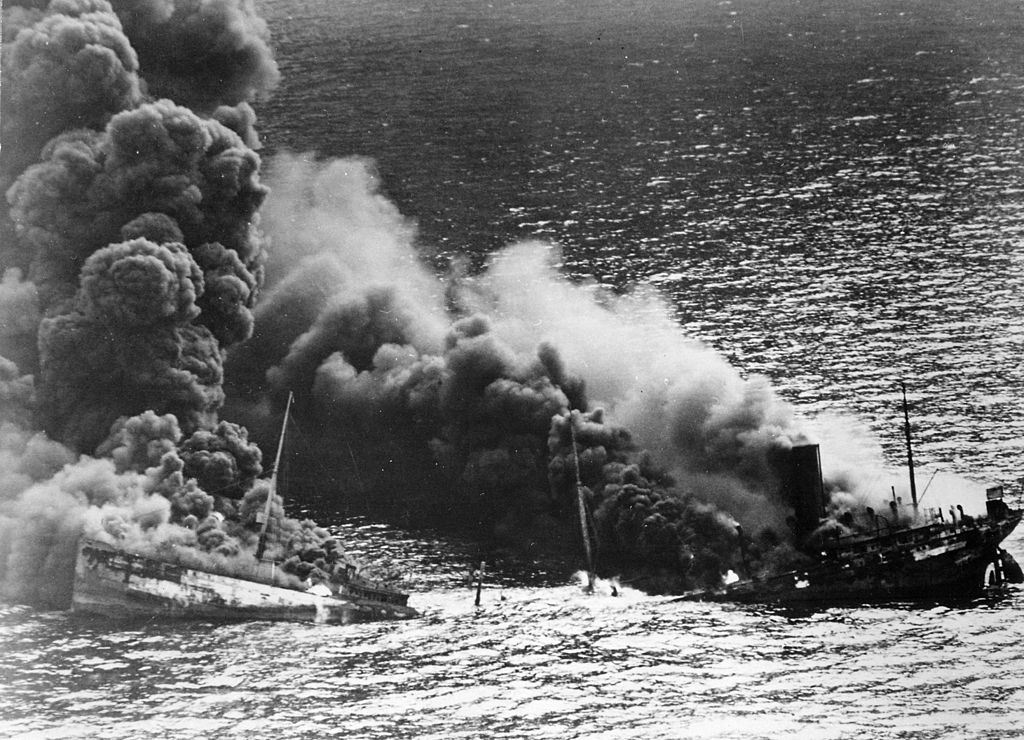

The Second World War was fought on multiple continental and oceanic fronts with a requirement to support not only American, but also Allied forces under Lend-Lease. With the U.S. Pacific Fleet forward deployed to Pearl Harbor, and the Atlantic Fleet escorting convoys to Europe and reinforcing the British Home Fleet, the nation was poised to support the Allies. When the United States entered the war in December 1941, the nation itself fell under immediate attack with a fleet of nine Japanese I-Boats and five German U-Boats arriving off the west and east coasts of the nation. As the planes of the Kido Butai were unleashing their attack on Pearl Harbor, I-26 sank the U.S. Army chartered freighter SS Cynthia Olsen enroute to Hawaii, with the loss of all onboard. While the Japanese submarine offensive would be limited, it caused hysteria along the West Coast, particularly after a surface attack against an oil refinery off Santa Barbara by I-17 on February 23, 1942.

On the East Coast, with Hitler’s declaration of war on America on December 11, 1941, Admiral Karl Dönitz dispatched all his available long-range Type IX subs to raid American waters. These five boats, part of a much larger vanguard that in the first half of 1942 sank 609 ships of 3.1 million tons, found the East Coast, the Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico devoid of American escort ships and unprepared. The reason for this has been laid directly at the feet of the new commander of the U.S. Navy, Admiral Ernest J. King, and in early 1942 he was confronted by a difficult situation.

King was responsible for all U.S. Navy forces and he faced a situation more challenging than the First World War. In this case, King had to deal with the need to protect trans-oceanic convoys not only across the Atlantic to England, but also across the Pacific to Hawaii and as far as Australia and New Zealand. He also had to oversee the immediate shipment of units to replace forces needed in other theaters. This forced King to prioritize the allocation of escorts, leaving ships on the east coast unprotected. This lack of suitable escorts is a situation that the United States finds itself in again.

There was also the issue of the divided command structure regarding American sealift and merchant marine forces. Pre-war agreements called for the Navy to assume control of the Army Transport Service, which meant replacing their merchant marine crews with naval personnel, but in May 1941, the Navy was unable to do this due to the lack of personnel. Later when war was declared, and the submarine offensive in full force against the United States, the issue over the role of command came to the forefront.

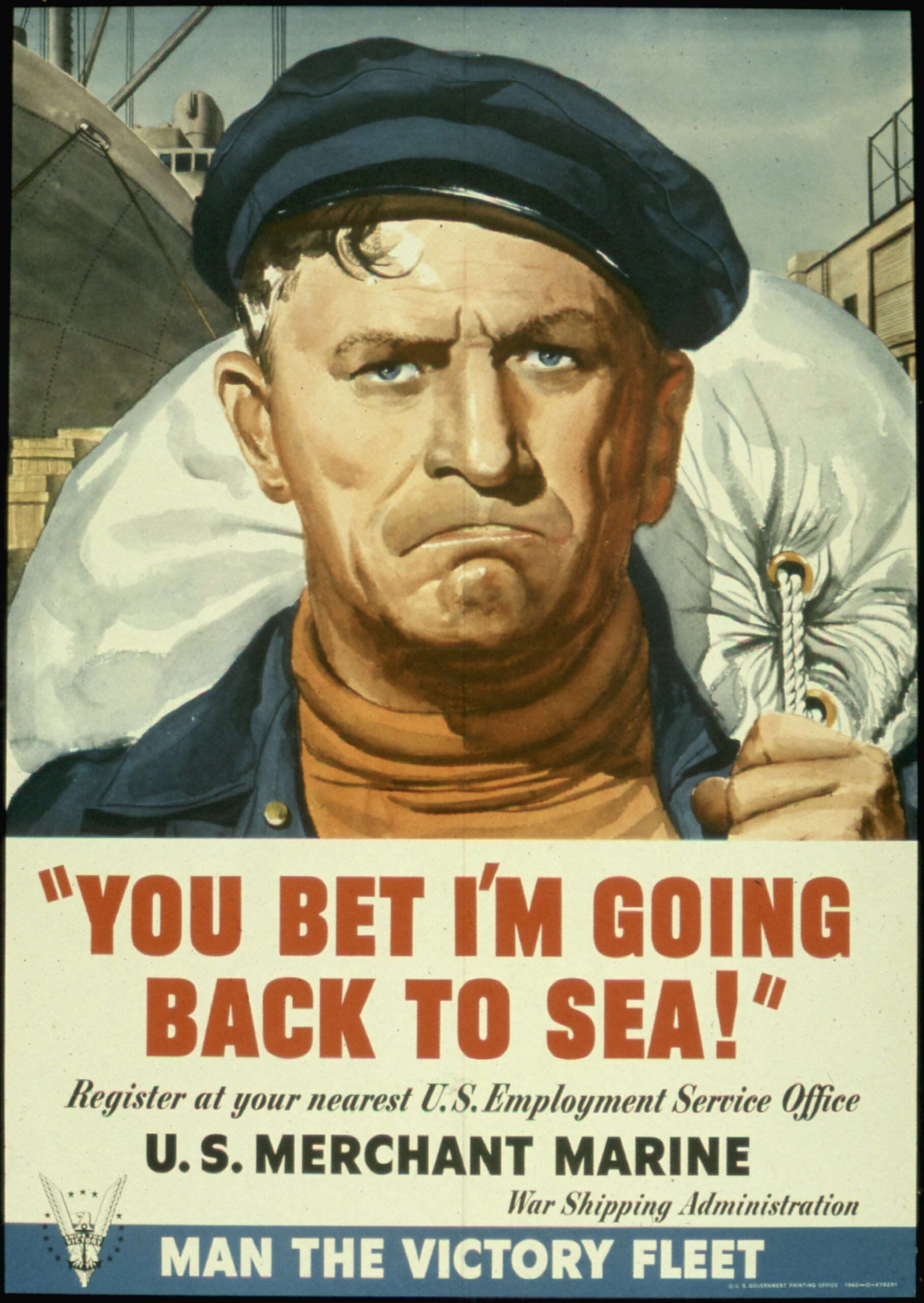

Vice Chief of Naval Operations, Vice Admiral Frederick Horne wanted to militarize the merchant marine as the Navy did in World War One. His concept was to create the War Overseas Transportation Service, but his plan was stopped by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Instead, FDR placed the management of the merchant marine under the U.S. Maritime Commission, with the creation of the War Shipping Administration (WSA) under Emory S. Land on February 7, 1942, which included all U.S. flagged merchant vessels on April 18, 1942.

In the First World War the United States Navy assumed a greater role in the oversight and management of the sealift operation. In the Second World War, Emory Land, through the U.S. Maritime Commission, had to build the ships; the War Shipping Administration had to operate the vessels through commercial firms; and the U.S. Maritime Service had to train the crews and oversee the sealift and merchant marine operations for the nation.

As Land supervised this, the Navy and military greatly benefitted from the early resumption of American commercial shipbuilding started under the Merchant Marine Act of 1936. With the nation in the Great Depression and many shipyards and shipyard workers unemployed, Land initiated a program to build 500 ships in ten years. With a series of standardized ship designs to choose from, the first 50 ships in the program proved essential to American victory with 37 taken over by the military as auxiliaries; this was later expanded to oversee the construction of emergency Liberty and Victory-class freighters and T-2 tankers.

Perhaps the best demonstration of why a viable maritime infrastructure and commercial merchant marine is so essential in a peer-to-peer conflict is to look at two specific examples. The first is the amphibious forces used to invade Guadalcanal in August 1942 as part of Operation Watchtower and Operation Torch off North Africa in November 1942. In both those operations, which spanned two different sides of the globe, the troop transports, cargo ships, and oilers used to land American forces and support the fleet all came from the commercial merchant marine. They were either built under the U.S. Shipping Board program of the First World War, during the interwar years, or a result of the U.S. Maritime Commission’s efforts. Additionally, many of the follow-on troops, cargo, and fuel were transported in commercial ships of the merchant marine.

The second example is the 12 T-3 tankers built as part of that initial 50-ship program which included specific National Defense Features that allowed for their conversion into naval auxiliaries. The ships included larger than normal engines and twin screws for higher speed. They were built to a higher standard to resist damage, and while many of them entered commercial service, several were immediately taken over by the Navy for conversion into fast oilers. Whereas the previous class of oilers were limited to 14 knots and 100,000 barrels of fuel, Cimarron T-3 tankers could sail at 18 knots and carry 150,000 barrels of fuel, allowing them to support the Navy’s fast carrier task forces early in the war. Throughout 1942, wherever USS Enterprise, Yorktown, Hornet, Wasp, Lexington or Saratoga steamed, so did Cimarron, Guadalupe, Neosho, Platte, Sabine, and Kaskaskia, backed by several dozen slower WSA tankers hauling fuel from the U.S. to forward bases or rendezvouses with the fast oilers. While eight were converted into oilers, four underwent conversion into escort carriers of the Sangamon-class. With only USS Ranger left in the Atlantic at the time of Operation Torch, the four Sangamon ships filled the temporary role of a fleet carrier.

The merchant marine was essential to Allied success in the Second World War, and one can read comments by the principal military commanders attesting to their essential role. Yet most histories record very little about this, including those of the U.S. Navy. In Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil: The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II, the merchant marine is present early in the war, yet later, as the Navy success mounts, the merchant marine disappears from the narrative. While the mobile bases and service squadrons provide direct support to fleets off the Marianas, the Philippines, and Okinawa, War Shipping Administration tankers and freighters are sailing to forward bases with little fanfare, even though these ships suffered losses at the hands of Japanese forces off Mindoro and Okinawa. Even Samuel Eliot Morison paints a very dim view of the merchant marine and this has tarnished their image in most post-war histories. The one branch that elevates the sealift and merchant mariner is in the official Army history, the Green Books, that puts shipping as the great limiting factor of the war.

With victory in 1945, the U.S. merchant marine emerged from the war having lost 733 ships and over 9,500 personnel. The merchant marine and the Navy had grown from the second largest on the ocean to the most dominant naval and commercial force the world had ever seen. It is estimated that American merchant ships transported 63 percent of the world’s trade in that last year of the conflict. While the Navy remained prominent, with no enemy competition, the merchant marine began to decompensate.

To rebuild the world, the Ships Sale Act of 1946 aimed to restore depleted merchant fleets with surplus American-built Liberty freighters and T-2 tankers. The Marshall Plan of 1948 provided loans to rebuild destroyed and damaged shipyards and incorporate the prefabrication method used by Henry J. Kaiser in America on a massive scale. Additionally, the use of the Panama registry prior to U.S. entry in the war to circumvent American neutrality laws proved enticing to ship operators as it did not have the follow American rules, crewing practices, or pay U.S. wages.

The door was open for the U.S. Navy to be the dominant force on the world’s ocean. But meanwhile the American merchant marine was facing mounting challenges.

Read Part Two here.

Salvatore R. Mercogliano is a former merchant mariner, having sailed and worked ashore for the Military Sealift Command. He is an associate professor of history at Campbell University and an adjunct professor at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. He has written on U.S. Merchant Marine history and policy, including his book, Fourth Arm of Defense: Sealift and Maritime Logistics in the Vietnam War, and won 2nd Place in the 2019 Chief of Naval Operations History Essay Contest with his submission, “Suppose There Was a War and the Merchant Marine Did Not Come?”

Featured Image: Aerial starboard side view of the Military Sealift Command (MSC) strategic heavy lift ship USNS WATSON (T-AKR 310) underway on sea trials off the coast of San Diego. (Photo via U.S. National Archives)