Assembled and edited by notetakers Professor Mie Augier and Maj Gen (Ret.) William F. Mullen, USMC

When General Alfred Gray articulated his vision for education (which resulted in, among other things, the establishment of Marine Corps University), he noted the importance of the topics central to educating agile minds – thinking and judgment rather than knowledge – as well as the process of learning: cultivating judgment through active learning approaches.1 Recent leaders have also noticed the importance of active learning approaches, and tried to nurture traits and skills that can help develop agile minds (and perhaps also agile organizations). The Commandant’s Planning Guidance, for instance, noted that while many of our schools are based in the industrial age model of “lecture, memorize facts, regurgitate facts”, we need instead an approach focused on “active, student centered learning.” As a result, greater emphasis needs to be placed on skills and attitudes such as critical and creative thinking, holistic problem solving, and lifelong learning – all of which are key aspects of education in the post industrial/cognitive age.

The discussion below features composite answers from five students who were part of a Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) elective course on Maneuver Warfare for the Mind: The Art and Science of Interdisciplinary Learning for warfighters.2 They share their thoughts on some topics relating to learning, the role of active learning, and their suggestions for improving how we educate learning leaders for the future. Their answers have been edited and condensed for this format.

Q: What were your experiences with active learning approaches and why do you find them useful?

A: One example from when I was in a squadron was that once a month we would read an article and talk about it. But we did not – as we have in this class – connect it much to our lives in our organizations. That [difference] is something I will bring back from this class. When I find an article that is relevant for my sailors to read, we will discuss how it connects to their job and organization.3 Learning with cases – or using examples as cases – also tends to cultivate more thinking and engagement than lectures, as it captures real world organizational dynamics relevant to warfighters. Importantly, examples or cases have ambiguity and ill-structured problems so learning is focused on the process of thinking and learning, not (just) the answers to the problems. Active learning approaches also usually invite students to think together and work in groups and teams, which engages not only cognitive but also social, emotional, and affective skills.

Talking about active learning in class is not enough. There are examples of using the right words, but doing it through textbooks and PowerPoints risks reducing education to simply transferring information to be memorized. It is not that PowerPoint has no place in active learning approaches – to illustrate a question, a puzzle, or a paradox for example can be a great lead into a discussion to help develop a questioning attitude central to learning – but too much informational content on a slide can easily narrow creative and critical thinking (e.g. ‘is this what the teacher wants us to know/think’?), or efforts to memorize what is on the slides.

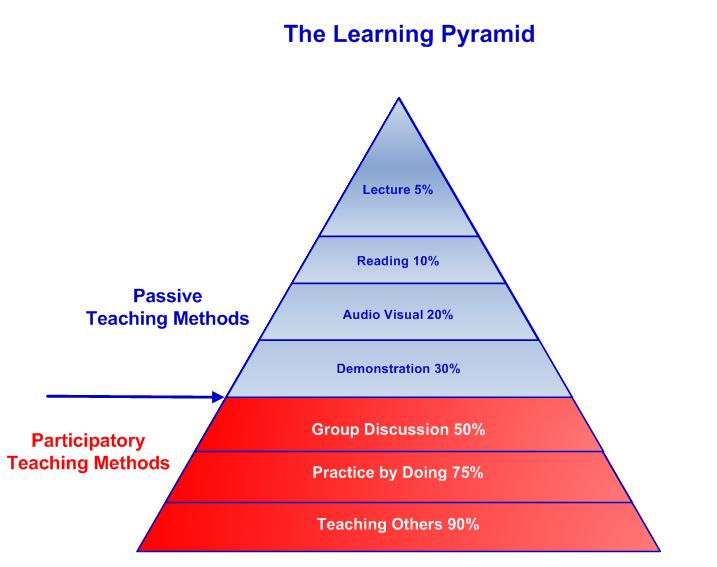

Memorization is not learning. Discussing the material, having smaller group discussions, and sometimes coming up with ideas to teach others, combined with some of the active learning approaches in the learning pyramid is true learning. Wargaming and force-on-force exercises are also active ways to learn, especially if they are unscripted.

In addition to the course’s delivery style, having it open to both resident and distance students makes the learning environment broader and more interdisciplinary. This speaks to the importance of enabling hybrid classes. There’s a richness to having students from different curricula and schools on campus as well as and outside of campus.

Q: What difficulties or barriers to active learning have you experienced?

A: We read an article by Herbert Simon about learning occurring in students’ minds.4 This means also there is a different role for teachers. Students are the focus, but everything is still guided based on the readings and the questions posed by the instructors. Some of the best classes we had within the course were those that had almost self-generated momentum that arose out of the readings and initial questions.5 Doing that successfully can be hard to achieve if both students and teachers are new to active learning approaches.

I have found some instructors have been very deliberate in bringing this approach into some of the courses, but most do not discuss, or ‘count’, the learning process as part of the learning being discussed and communicated. I think there is a lot of value in the process of discussion, in working together, and in bringing together different viewpoints. It helps achieve the kind of learning we talked about in Boyd’s conceptual spiral with the generation of novelty and synthesis being very important.6 That is very different from the memorization approach, and it encourages us to value thinking, reflection, and reframing as part of the learning process and as a way to develop new ideas.

Mortimer Adler in his classic work on education (Reforming Education) mentions how the doctrinal approach to learning (present in industrial age approaches) indoctrinates knowledge and information (with no room for failures or errors). Textbooks that are often written from disciplinary silos reinforce this, creating a barrier to interdisciplinary learning and understanding. The alternative approach – the one more suitable for cultivating thinking and interdisciplinary learning skills – is dialectical; teaching students how to think through engagement and thinking through difficult and contradictory ideas and information. It also cultivates broader problem-solving skills instead of just those focused on a particular issue.

Teachers are not ‘instructors’ in the sense of transferring information or simply teaching a tool through which one can view (some part of) the world; but are themselves learners and interact in the discovery process of identifying, framing and reframing problems, thinking through hypotheses, etc. This is more difficult on both sides. Students have to get used to not having textbooks, checklists and rubrics for everything. And teachers have to be much more adaptive in their planning and execution and be able to lead discussions through problems and dialogue, not through power points. But both sides can really learn. In our domains (warfighters and warfighter organizations), an emphasis on two way street learning also helps ensure an interdisciplinary mindset and a focus on problems and issues relevant to warfighters and warfighter organizations.

Q: Were there any particular readings, or ideas, or themes, that you have felt have helped you as a learner?

A: Something that came to my mind was the discussion we had about a growth mindset and active learning as well as the neuroscience behind it, and what it means and why it is relevant for us. Underlying the growth mindset approach is the belief that we can always grow and improve as thinkers and learners. The importance of engaging in problem solving activities in class and the fact that this approach engages different pathways in the brain than when memorizing was very interesting. The need for a growth mindset in warfighters was demonstrated also. That discussion changed my outlook on a lot of things. It has also been found to have a positive effect on performance and motivation, thus helping to build intrinsic motivation essential to lifelong learning.7

I really enjoyed the scenario planning and counterfactuals discussions, those were different dimensions of learning, or complementary dimensions, to the discussions about the dynamics and mechanisms of individual and organizational level learning. When you add the aspect of learning from the future, and you use creative thinking to imagine those futures, you also learn to see history through counterfactuals, and how fiction can and cannot be used – that stuck with me (see e.g. Fiction | Center for International Maritime Security). Also, when we are trying to understand particular periods – e.g., the U.S. Marine Corps in the 1980s – the counterfactual thinking is interesting, that’s what I’m carrying with me.

There was also a sense of learning from different mediums. We read books and articles (as well as a book about how to read books); but we also had podcasts and even the military reform testimony on C-SPAN that was useful in content and approach. That discussion showed that while we may think of that movement, the military reform movement, as one perspective, it really was a collection of individuals who shared some ideas but nevertheless were able to advance a movement, as Boyd mentioned. It was interesting to hear how some learn best from reading, some from audio books, some more visually, and we got ideas for how to increase our own learning skills.

In his “Invitation to the Pain of Learning” Adler discusses how we read and learn, which brought to me the importance of the questions we have in our minds when we read things, and how we bring particular articles and ideas together with other readings – which is synthesizing in Boyd’s terminology. That helps us build interdisciplinary understanding and range. Also, the importance of questions, and a questioning mindset – asking ourselves, what great questions did we ask? — is something we can bring in more too, and is much needed for warfighter and warfighter organizations today. For example, as we seek to understand competitors (in the great power competition context), we have to question whether we really understand them well and seek to learn more about how they think (not just observe what they do).

Q: Have you had any moments outside of class where you have found this type of learning useful for you?

A: The first weeks, when we first started, I was in an integrated planning team and I was using concepts from this course to make changes for my team. So my job actually has tracked well with the course. I am not sure my ideas will be implemented, as organizations tend to resist change, but it resonated with me.

Another experience that I connected to this course was during a week of assessment, physical, oral interviews, evaluations – some challenging and some routine. The oral interviews were focused – what directly translated for me was the usefulness of reflection, self assessment, mentoring, giving and receiving mentoring, and being a lifelong learner. Those themes were very useful for me since the interviews focused on evaluating if people are really mentoring.

There’s a timing issue too that turned out to make our discussions particularly relevant. What did we learn from Afghanistan? With all the talk about us being learning organizations and learning cultures, should we think about what that means after 20 years there? What does it mean for me? For our organizations? For how we talk and see ourselves as a learning organization? As a learning nation? Many of the mechanisms and dynamics of learning are applicable to us as individuals, organizations, and as a nation. They play out differently in different contexts but examining the fundamental mechanisms in difference contexts we live through is important.

Even if Afghanistan is a failure, we can learn from it if we understand what happened; what went wrong; and reflect on our experiences.8 Learning from failure is not easy and involves overcoming individual and organizational barriers to seeing mistakes as mistakes in the first place; and to learn from them through reflection. Organizational leadership scholars have argued that willingness to talk about failures and mistakes and encouraging open discussion and questions is a useful first step. Cultivating a questioning attitude and ability to reflect are important steps towards being able to learn.

I also think this is a unique point in time not just in terms of the strategic environment, but organizationally too. In particular, the USMC is going through a massive shift with new guidance, new organizational documents (e.g. 2021 Force Design Annual Update; Talent Management 2030; MCDP 7; MCDP 1-4), etc. – is it really a learning organization? Does it have what it takes to adapt? This course also helped me understand why we are doing some of the things we are doing now.

The topic of learning is not just important for understanding how we learn as individuals so we can improve, but also organizationally. How do we build better learning organizations, better learning cultures?

Q: Do you have any suggestions you have to help us and our leaders move more fully beyond industrial age approaches?

I almost think a class like this should be mandatory at NPS because there is so much of what we talk about – mentoring people, being a good leader, etc. – but we do not talk about the why’s or the learning processes behind things. We say things are important, but we don’t go into details of why. So I feel like discussing learning and applying it has been important in my professional development beyond and in addition to the particular learnings.

We aren’t really told about the electives; some even have preloaded matrices. So maybe we can get better in making sure students are aware of the elective space they have and maybe make sure the descriptions relate to how the course is useful for us in our organizations.

Where I am, our curriculum is a lot more flexible and we probably have more electives, but I have friends in some of the other curricula where in most— if not all— classes, they are given all the information, all the homework, very traditional, and then a test in the end – where students are mostly in receive mode.

That also indicates the complementarity of approaches. In some domains with well-structured problems, that style of learning might work.9 Traditional learning also helps you baseline a lot of learning so it might be efficient to bring people through the system. But memorization is not learning– so it might be efficient, but not effective.

Instructors need to embrace active learning, too, and be able to teach it in the context of relevant problems, not just theories. We also need to hire the right teachers — you have to make sure they are comfortable teaching in active learning environments. Course designs are important too. Courses have to be developed by people who know how to use active learning in their fields.

It also goes back to the fixed vs. grown mindset piece. Teachers need to be lifelong learners, too. Active learning is a two-way street. A growth mindset and lifelong learning implies that learning is continuous and valued both inside and outside our schools and educational institutions, in both students and teachers.

Along those lines, one thing, at least from a Naval Special Warfare perspective, is that there seems to be a deeper, maybe even ‘paradigmatic’ change happening. People used to go to educational institutions and they would almost be ‘checked out’ – people didn’t have to report anywhere; they could just play golf – they had a lot of downtime and there wasn’t really an intellectual emphasis. People would write a thesis that no one read, etc.

That has shifted, at least in my community, so now the guys coming to NPS are given guidance about projects and direction towards operational impact. Before, people would come back after education and folks would say ‘I thought you got out’. But now, while at NPS, they are in continual communication with people in their community. So that makes the change more comprehensive in a way; with the learning mechanisms between the communities and the students adding to building learning organizations and learning cultures – that also helps build the intrinsic motivation we have talked about.

I see a culture-wide paradigm shift in attitudes towards learning and education. As the remaining industrial age proponents move out and retire, that could be really important.

Q: Some of the discussions and readings we had were about mistakes and failures and the centrality of those in organizational adaptation. How do we learn to get better in allowing failures so we can learn from them?

A: The growth mindset piece really struck out to me. Task setbacks are necessary parts of the learning process. Without failures, we are unlikely to grow and learn. I am learning that lesson from my last command where we were not given the opportunity to fail. I got my job and got good at it and we were supposed to rotate but didn’t get to rotate since someone left. But I’m here as a junior officer and I am supposed to get opportunities to learn but there was no mentoring, no room for failure, so I know now the importance of giving others freedom, guidelines, and support, to fail.

I think we have to put people in positions where they know they will be allowed to fail – so incentivizing failures, and making it part of the process, even part of our classes, if necessary for learning. We had a discussion about how to build in failures in our organizations. We can build them into our courses and learning environments, too.

Closing thoughts

While active learning approaches are not new, the need to enable military professionals to think on their feet and have the mental agility to adjust to changing circumstances has never been more imperative. Technology is changing at the rapid rate and becoming both less expensive and more widely proliferated. Our potential opponents are already acting in areas referred to as the “gray zones” to get what they want without having to resort to armed conflict. In the event of armed conflict, those same potential opponents will not fight the way we would like them to, or that we have been training to for many years. They understand our strengths and weaknesses perhaps better than we do and will seek to fight as asymmetrically as possible. This is not something that is new either, but we seem to have more challenges adapting to the fight we are in when we do not encounter the type of fight we are prepared to engage in. This trend cannot continue, and it can only be overcome by educating thinking, continuously learning leaders who have the ability to interpret what is happening in front of them and make the necessary adjustments to fight appropriately in short order.

Kevin “KP” Peaslee is a Contracting Officer (64P) in the United States Air Force. KP has 18 years of military experience ranging from Security Forces, Inspector General, and Acquisitions. Additionally, KP has a Master’s in Strategic Purchasing, a Master’s in Homeland Security, a Bachelor’s in Business Administration, and an Associate’s in Criminal Justice.

LT Benjamin P. Traylor, USN, is an Aerospace Maintenance Duty Officer, currently MMCO at VUP-19. Served as MCO/QAO for VAQ-133, IM 4/2 Division Officer on CVN-72. He has an MBA/Material logistics from NPS and a BS from Western Michigan University.

LCDR Morgan O’Neill has been serving within Naval Special Warfare since 1996 and continues to find new things to learn along every step of the way.

Major Leo Spaeder (USMC) currently serves as MAGTF Planner at Headquarters Marine Corps.

Major Matthew Tweedy, USMC, is an infantry officer who recently graduated from the Naval Postgraduate School.

The notetakers from the conversation were Professor Mie Augier and Maj Gen (Ret) William F. Mullen.

Endnotes

1 A discussion of some of the elements is here: Maneuver Warfare for the Mind, Educating for thinking and judgment (nps.edu). A key historical document is Gen Gray’s memo, “Training and Education”, October 10, 1988, located in the Alfred M. Gray Collection, Box list Part 2, Box 6, Folder 12, Center for Marine Corps History, Quantico, Virginia.

2 The course (GB 4012) seeks to integrate key ideas in the interdisciplinary areas of the art and science of learning; concepts, mechanisms for individual and organizational learning, as well as learning from the past and the future, all with an eye towards applying these concepts to developing warfighters, warfighting organizations, and warfighting leaders. The discussion was typed by the note takes and edited for overlaps & readability.

3 Making connections and building analogies between concepts, readings, and own life and organizations are themselves activities that can build greater cognitive flexibility.

4 Herbert A. Simon, “Problem Solving and Education”. In D.T. Tuma and F. Reif, Issues in Teaching and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlhaum Associates, 1980.

5 This insight is central to the approach to teaching judgment sometimes referred to as “discussion leadership” (see C.R. Christensen, D. Garvin and Ann Sweet, “Education for Judgment: The Artistry of Discussion Leadership”. Harvard Business School Press)

6 A good article about Boyd’s conceptual spiral is available here: “John Boyd, Conceptual Spiral, and the meaning of life.”

7 Ng, Betsy, “The Neuroscience of Growth Mindset and Intrinsic Motivation,” Brain Sciences 8, no. 2 (Jan. 2018).

8 An example of a reflective paper integrating recent events with literature with education is Reflection on Failure By Major Matthew Tweedy, USMC (themaneuverist.org).

9 Recent research has pointed out that active learning approaches are advantageous not only to teach ‘soft’ skills and behavioral science approaches; but also STEM topics (see, e.g. Freeman, Eddy, MC Donough, Smith, et al (2014): Archive Learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Featured Image: Students at NPS (Photo via Naval Postgraduate School)

I am not a trained educator although I have logged a lot of time teaching at the Naval War College as well as leading the Wargaming Department and later the Center for Naval Warfare Studies. In terms of active professional learning, here is what I have found:

1. Critique is not enough. Clausewitz extols “kritik” as the key to learning about war, and he has a point. The use of case studies is a good starting point for professional education but it is not enough,

2. Information is best retained through personal research. Assigned reading might be necessary, but a student who has to decide what kind of information is needed and goes looking for it is more likely to retain it. For the Navy, researching classified capabilities in order to develop a course of action creates knowledgeable tacticians.

3. True education requires the student to grope with problems that are not clearly defined . It is not enough to find solutions, the problem itself must be defined.

4. At least some problem solving should occur in a competitive environment. Two-sided wargames are needed for this. Students should experience the consequences of deciding on a particular course of action – not feedback that indicates deviation from a school solution but by another player that is trying to win at your expense.

Seminar discussion is not true active learning despite what academics assert.