By Drake Long

Introduction

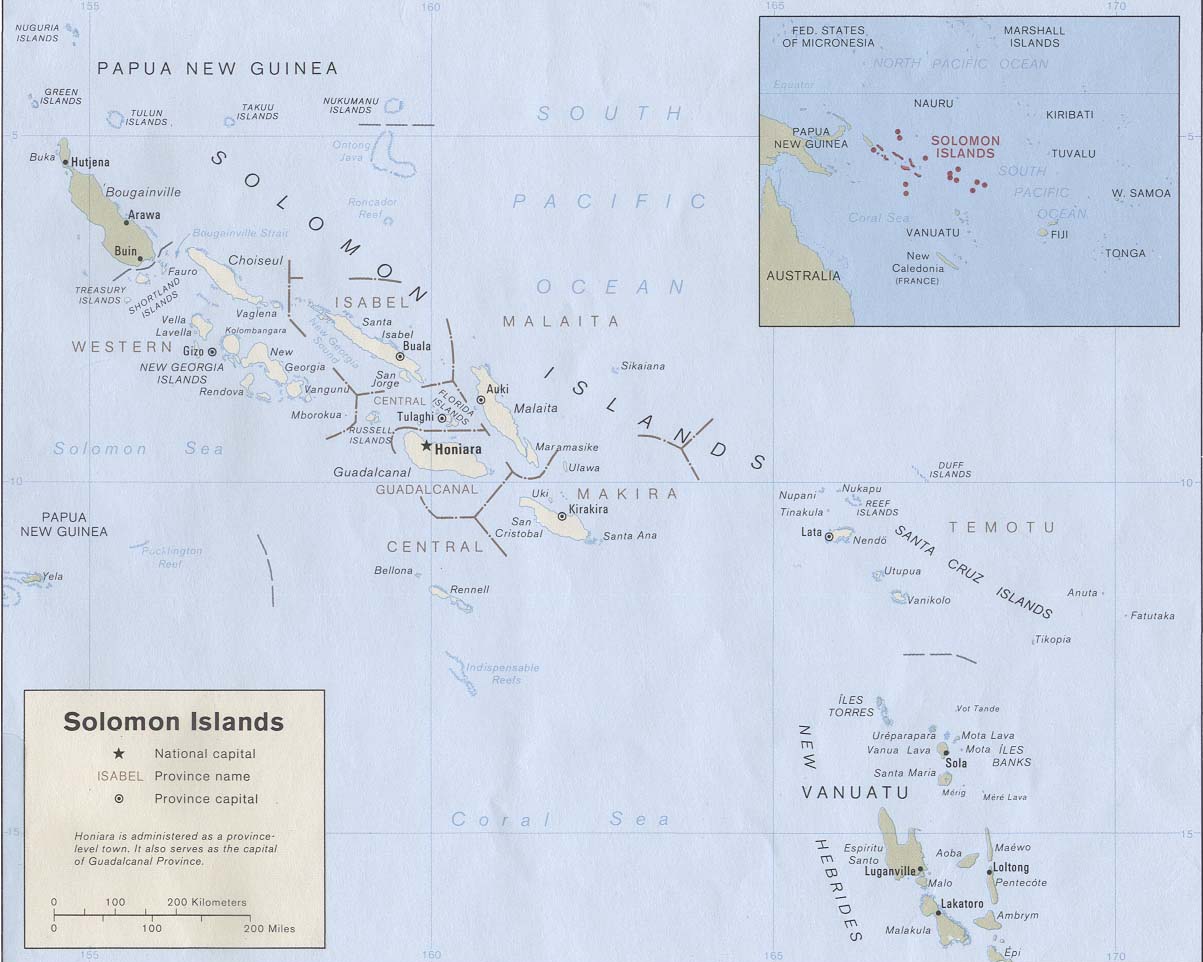

In 1567, a Spanish navigator named Álvaro de Mendaña y Neira set sail for an ill-fated voyage to Oceania. His mission was to find a stopover for the famed Manila Galleons, ships carrying supplies and looted resources between the Spanish colonies in the Philippines and Peru. Where he landed was an undiscovered island in the South Pacific christened Santa Isabel, but his crew ultimately encamped for three months in an area further north dubbed Guadalacanal. Both locations are better known in the modern day as part of the Solomon Islands.

The expedition did not go smoothly. Neira intended to set up a permanent Spanish colony, but his party’s hostility toward the native Solomon Islanders and unfamiliarity with the local terrain led to constant, bloody clashes, starvation, and death. The Spanish mission fled Guadalcanal in failure in 1568. Spain attempted a similar mission some 30 years later with the same outcome.

Plans to establish a base in the Solomon Islands for the benefit of the Manila Galleons were ultimately shelved. The resistance of the Solomon Islanders and dearth of resources on the archipelago itself led Spain to think the Solomons were more burden than blessing. Spain decided the islands offered no strategic economic benefit whatsoever, and moved on.

Over 300 years later, a very different empire with different goals looked at the Solomon Islands and came to a separate conclusion. Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue, commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 4th Fleet, saw in the Solomons an ideal position for land-based aviation and advocated that the Empire of Japan seize it in an amphibious campaign. From the Solomon Islands, aircraft could place the encroaching Allies and their navies under a threatening bomber and torpedo umbrella. This assumption proved correct, and the Solomon Islands preoccupied Allied attention in the opening phases of the Pacific war.

Now the Solomon Islands has found itself at the center of attention yet again. It switched recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China in 2019 and has shocked its neighbors by courting something akin to a security guarantee from Beijing. Yet anyone with a stake in the South Pacific should have known the domestic political environment in the Solomons would lead to this point.

There is a specific criticism leveled at the United States from its partner-nations in the Pacific and Oceania – that it is not sufficiently committed to the region. There is some validity to this statement. The Solomon Islands, despite having featured prominently in the annals of history for virtually every previous major maritime power in the Pacific, has only just now become a major point of consternation for the United States (and Australia), after its downward spiral into another bout of domestic political upheaval is too far along to stop.

To other nations in the Pacific, the United States does not seem to proactively adjust its foreign policy to counter new threats, so much as it reacts to events. The opening of new embassies in the Pacific Islands well after the PRC already did so epitomizes this late-to-the-party approach.

This is not the approach the combined U.S. naval services want to take, according to the priorities laid out in the Triservice Maritime Strategy. The U.S. naval services are redesigning themselves to better compete day-to-day with other maritime powers, including by inculcating a mission command mindset into all components of U.S. maritime power and integrating the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard into unified instruments of naval diplomacy and engagement with partner nations.

But to really serve as an effective steady-state influencer deeply involved in great power competition, the U.S. naval services need to invoke the roadmap laid out in the Triservice Maritime Strategy to create more than mission commanders. The services need to create a cohort of geostrategists.

Building Geostrategy

Both Spain and Imperial Japan, when looking at the physical characteristics of the Solomon Islands, were practicing a form of geostrategy. Geostrategy calls on states to rank and prioritize the criticality of physical features according to the national interest. Chokepoints, straits, and sea lines of communication are all terms for things geostrategists define, value, and then consider how to defend or exploit.

One of the core tenets of geostrategy is that physical geography does not appreciably change. However, political and economic geography do, and the above (simplified) story offers a case study in how geostrategy can adjust accordingly. For the Spanish Empire, the motivating factor to explore the Solomons was in service to a trade route between two other colonies. Ultimately though, the ill-fated expedition to the Solomons proved it was not as relevant to the economic geography of the Spanish Pacific as some navigators thought.

Imperial Japan saw in the Solomons a method of protecting vulnerable sea lines of communication, and a way to further project its airpower to threaten the Allies. Most historians of the subsequent Guadalcanal campaign would probably argue the Solomons’ geography did end up being an important factor in the Empire of Japan’s favor at the outset of the war.

Navalists – which in this context does not just mean members of the U.S. naval services, but also shipping industry executives, oceanographers, marine scientists, and maritime law experts – are inherently geostrategists. Be it their profession, hobby, or subject of academic inquiry, seapower hinges on the relationship between different physical geographies – the oceans and landmasses. Maritime shipping ultimately connects inland economic resources to littoral economic hubs. Marines require a Navy to trek across bodies of water to their next crisis. Environmentalists focused on healthy seas have to contend with toxic shipbreaking practices and other forms of environmentally disastrous work close to the shore.

It is impossible to be a navalist assigned to think about and work with seapower without considering the physical geography of the world and the maritime domain. Alfred Thayer Mahan, perhaps the most famous maritime geostrategist of all, implicitly explained this on a deeper level in his famed book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History.

The problem all maritime states have in the modern day, including the United States, is that they are not cultivating navalists as geostrategists, or in other words, a cohort well-suited to the changing, global security environment. This is not to say the U.S. naval services do not create servicemembers steeped in global events or geography. The U.S. Navy in many ways epitomizes the navalist-as-diplomat mentality. But the Triservice Strategy itself places special emphasis on the phrase ‘rules-based’ order, a nebulous term that does not always resonate with the countries the U.S. needs to partner with for effective competition. There are multiple new facets – new geographies – in the geostrategic environment that the current rules-based order is not equipped to deal with. Rather than adapting, the U.S. risks hanging on to the status quo past its expiration date.

New Economic Geography

Geostrategy must appreciate how much of a sea change global commerce is currently experiencing. There was a brief period, roughly bookended between the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, where trade networks worked on an assumption of globalized supply chains and unfettered, just-in-time shipping. This would reduce costs and insulate commerce from many geopolitical frictions.

That era is almost certainly over. Trading nations are increasingly adopting policies of weaponized interdependence that use supply chains’ overreliance on them for strategic advantage. China, the United States, and the European Union, all titans of trade, are increasingly exploring on-shoring for manufactured goods and expanding their definitions of critical sectors to guard against dependence on rival actors to provide products necessary to national security. The reliability of trade is shifting as well. The cascade of effects from the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how incredibly fragile the global shipping industry actually is, and nations crucial to trade are increasingly securitizing key waterways like the South China Sea.

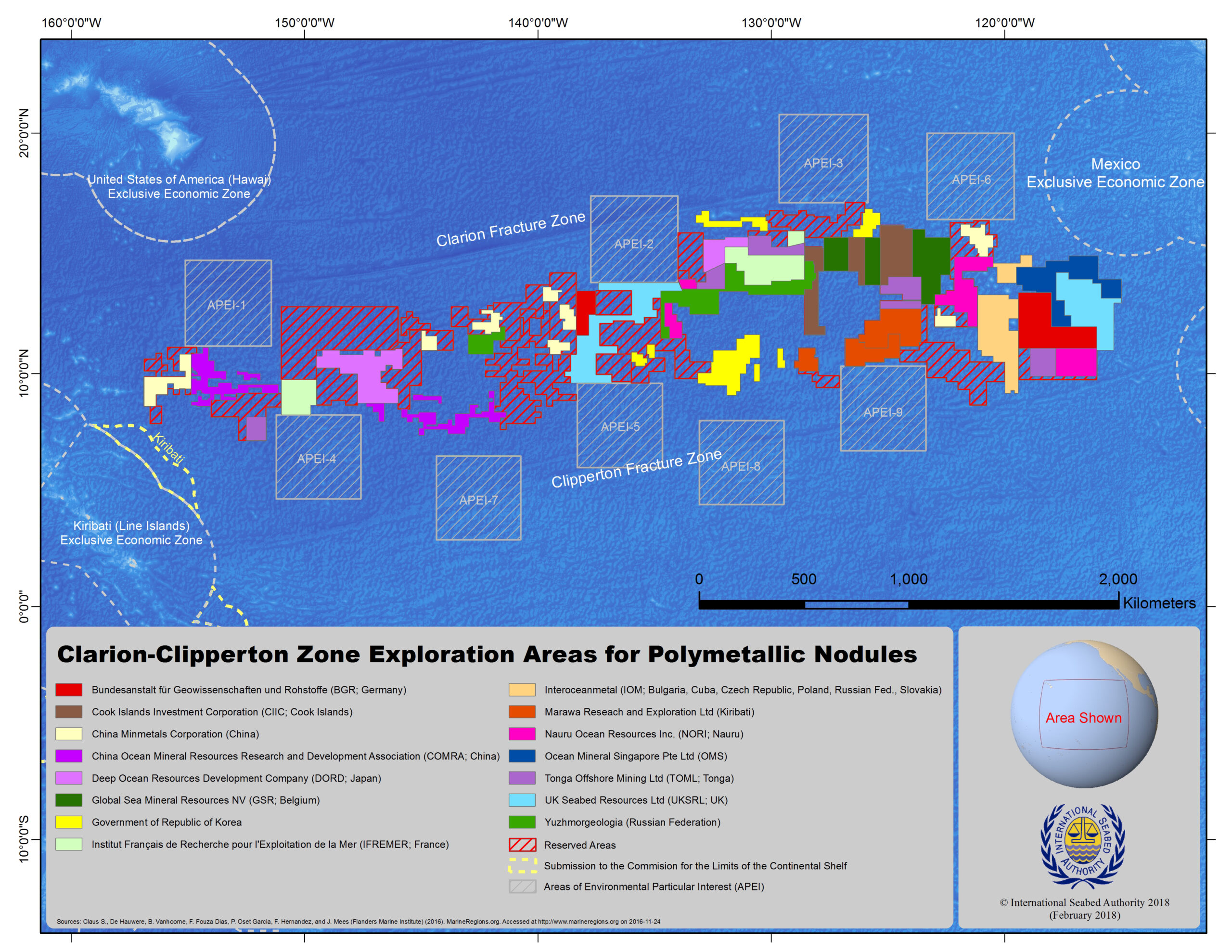

The sources of marine wealth are changing as well. The traditional understanding of maritime trade operates on a system not unlike what guided the Manila Galleons long ago. Trade flows from point A to point B, and geostrategy is set up around ensuring that trade is not vulnerable to disruption. However, centers of gravity in the maritime economy are moving further and further away from the coast and out into the open ocean. Seabed mining, marine genetic resource harvesting, and deep-sea fishing are all entering new phases of commercial activity within the next 10 years, where previously inaccessible resources are now within reach. This is significant because traditional geostrategy is focused on ensuring trade between ports is uninterrupted – usually by identifying key waterways and sea lanes. But increasingly, key maritime concentrations of geostrategic value could be on the high seas where there are major deposits of resources, such as the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the central Pacific.

The existing rules-based order does not have clear answers for these emerging developments. In search of a different solution, new treaties and rules are being actively sought out by countries with the most to gain from this new economic geography.

Educating Geostrategists

For a geostrategist looking at the changing economic geography and thinking of how the U.S. naval services fit into it, they would probably rely on precedent. Historical precedent is the most important skill to impart on the navalist-as-geostrategist. Yet to adequately find and draw on precedents, the U.S. naval services would need to make significant changes to professional military education and training. A rising cohort would need to embrace a more global curriculum that truly emphasizes maritime geostrategy from the perspective of revisionist states, allies, and partners. For example, most navalists can name Alfred Thayer Mahan – but can they name K.M. Panikkar, the post-colonial Indian seapower theorist that penned a sequel to Mahan’s work, going so far as to title it An Essay on the Influence of Sea Power on Indian History? They probably can cite it unwittingly – after all, within that circa 1945 essay Panikkar penned the modern-day understanding of ‘the Indo-Pacific.’1

The international relations field is already somewhat ahead of the curve on this with the development of Global International Relations, a specific subfield championed by the likes of Amitav Acharya. Global IR is predicated on the belief that other theories of interstate relations and regional systems outside of the U.S. and Europe are just as valid as the prevailing western-centric theories. This might seem intuitive, but these alternative views of seeing the world have only become more prominent after the long, lengthy process of decolonization, where the knowledge of non-European empires and seapowers were no longer discarded, ignored, or suppressed.

Geostrategy can embrace some of these same principles. As already pointed out, the understanding of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ changes when speaking to modern-day navalists in India, Japan, or the United States. Reconciling these differences can only occur when the U.S. raises a cohort of navalists that actually understand, on a deep level, why their allies and partners view the world the way they do.

In order to create these geostrategists, the U.S. naval services should invest in professional military education that stresses alternative ways of viewing the world. One method to do this is to significantly increase International Military Education and Training (IMET) programs and bring in navalists from other nations currently theorizing and codifying their own seapower strategies. They can interact and impart knowledge with U.S. counterparts – be they members of the Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard.

Another method is to set up incentive funds that promote wargames that emphasize playing and understanding ‘Green’ or ‘Orange’ states. These countries are not necessarily the primary combatants in an operational wargame, but may be allied to the Blue or Red Teams, or neutral, and are capable of tipping the balance of competition. Far too often wargames tied to professional military education stress the ‘great powers’ of a competition without understanding the relative strength of middle powers and even small states. If navalists empathized more with these resident powers of the Pacific, they would better appreciate their stakes in great power competition as well.

Finally, the U.S. naval services need to integrate outside of the military and facilitate professional development opportunities that expose its navalists to other maritime professions. The new geography of the world is not being charted by the military so much as marine scientists, economists, and environmentalists. As Arctic ice melts, the first person to explore the viability of a Northern Sea Route will likely be a shipping magnate. The bodies setting the rules for the ‘blue economy’ are currently centralized in the United Nations – many of which the U.S. naval services would be keen to keep an awareness of, if not sponsor an observer in. This would serve to better understand the concerns of Pacific Island states who see the orderly expansion of economic rights in their vast Exclusive Economic Zones as key to their economic development.

This civil-military integration could take the form of bringing more outside experts into the PME institutions that serve the naval services. The Naval War College, Marine Corps University, and Coast Guard Academy all have the flexibility to provide nuanced and intriguing discussions of the changing maritime world for their students. But this integration could just as well be served through sending servicemembers and navalists as short-term observers to international rules-making bodies and industry groups.

Conclusion

Geostrategists must be capable of understanding the intersections of Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard power in peacetime and in conflict. They must understand the new maritime geography the U.S. must take national interest in and conceptualize new operations to shape these areas and how American influence is projected. But members of the naval services are instructed to uphold the ‘rules-based international order’ without adequately understanding what came before it, who created it, and what could come next. Equipped with these understandings, they would better recognize the motivations driving great power competitors and revisionist states today – and therefore understand how to better influence geostrategy. That would be the first step to becoming a geostrategist and seizing the opportunities posed by the evolving geostrategic environment at sea.

Drake Long (Twitter: @DRM_Long) is a Pacific Forum Young Leader and a member of CIMSEC.

References

1. In Panikkar’s words, he called the Indo-Pacific ‘a strategic arc’ encompassing the east coast of Africa all the way to the easternmost islands of Southeast Asia.

Featured Image: ISS040-E-006780 (3 June 2014) — Clouds over the southern Pacific Ocean are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 40 crew member on the International Space Station. (Photo via Nasa)

I share your concerns, on many levels. The U.S. Naval services must invest in the art of geo strategy to become the navalists required to meet dynamic change in the Indo Pacific. China’s welcome in the Solomon Islands is another intelligence failure.

The US Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point would be an excellent place to start. Along with a renewed national maritime strategy to build and operate US-flagged merchant ships, the United States needs their own Belt and Road, or Port and Ocean. Our trade infrastructure has been neglected for too long.