Read Part 1 on Combat Training. Part 2 on Firepower. Part 3 on Tactics and Doctrine. Read Part 4 on Technical Standards. Read Part 5 on Material Condition and Availability.

By Dmitry Filipoff

Strategy and Operations

“During this time we have seen our once-great fleet cut almost in half and our remaining ships and personnel forced to endure long and continuous deployments as their numbers dwindled while requirements increased, and our nation turned away from international imperatives to attend to vexing problems closer to home…” –Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt, 1973

The Navy is not the only branch of the military facing significant challenges born from a long focus on the low-end fight. After the fall of the Soviet Union and especially after the start of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan all of the military services pivoted their training toward low-end skills to a significant extent. All of the services dealt with crushing operational tempo stemming from demand driven primarily by the Middle East, and are still paying off large maintenance debts. Now they are all trying to radically reorient themselves to be ready for great power competition.

However, the Navy stands far apart from the other services in how it contributed and adapted to the major wars of the power projection era. The nature of blue water naval power was poorly suited to counterinsurgency, causing the Navy to diffuse its efforts across a broad variety of mission areas. The fleet went on to suffer an especially large divide between what it could do and how it was tasked. Missions that were once considered a luxury afforded by the demise of a great power competitor eventually came to be regarded as inescapable obligations. This mission focus blurred the Navy’s priorities, allowed it to overextend itself, and helped blind the fleet to the fundamental need to develop itself through proper exercises.

As a result, many of the Navy’s operations undermined enduring strategic imperatives, suggesting the urgency of those low-end missions was built on questionable strategy. In the process, the Navy shed high-end warfighting skills that remained relevant even after the demise of the Soviet Union and is entering an era of renewed great power competition at a disadvantage as China rises. The United States, as a maritime nation, and the world, as dependent on maritime order, now find themselves at greater risk by an American fleet deficient in sea control.

Missions and Adapting to Power Projection

“Looking at how we support our people, build the right platforms, power them to achieve efficient global capability, and develop critical partnerships will be central to its successful execution and to providing that unique capability: presence.” –A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2015)

The composition of blue water naval power is often decided a generation in advance of when it actually manifests itself. It takes many years to conceive of a ship, several more years to then build the first ship of a new type, and many more years to build an entire class of ships. The fundamental attributes of the modern U.S. Navy were mostly set or inspired by the national security thinking of the 70s and 80s when sea control defined its focus. The American fleet that sails today is mainly composed of 100,000-ton nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, large surface warships that can carry over 100 missiles each, and nuclear-powered submarines. The modern U.S. Navy is a living relic of the Cold War, where its design was crafted in an era dominated by great power competition.

Something similar could be said for the force structure of the other military services, and the low-end focus of the immediate post-Cold War era demanded they all adapt. The nation-building and counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan required especially radical changes. Adapting to these wars took more the form of different missions and training, rather than building different kinds of force structure. Divorcing units from high-end force structure inspired by Cold War threats became central toward adapting to the low-end fight.

Both the Army and Marines recognized that a significant part of their force structure was barely useful for counterinsurgency and chose to rarely employ their armored units in traditional roles. It appears the U.S. did not deploy tanks to Afghanistan until 2010, and up until at least two years ago no Army armor units have deployed to Afghanistan with their tanks.1 Having been divorced from their main vehicles these units underwent extensive retraining to take on new missions, and the Army’s field artillery branch experienced similar reforms.2 Even though these units were pushed into less-familiar roles these adaptations were viewed as necessary to make them more applicable to the counterinsurgency fight.

The Army and Marines are not alone in having force structure that was hardly useful to counterinsurgency. Most of the tools of blue water naval forces such as powerful radars and sonars, dozens of missile tubes, electronic warfare suites, nuclear submarines, and long-endurance ships are poorly suited to fighting insurgents. Insurgent war is usually a land-only contest, where insurgents almost never field real navies. Aircraft carriers can employ airpower, but most of the Navy’s major capabilities could hardly be applied. This is reflected in how the surface and submarine fleets’ direct combat contributions to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were mostly confined to cruise missile strikes conducted in the opening months of those campaigns.3 Beyond that there were virtually no contributions of firepower from most American warships for the rest of these wars.

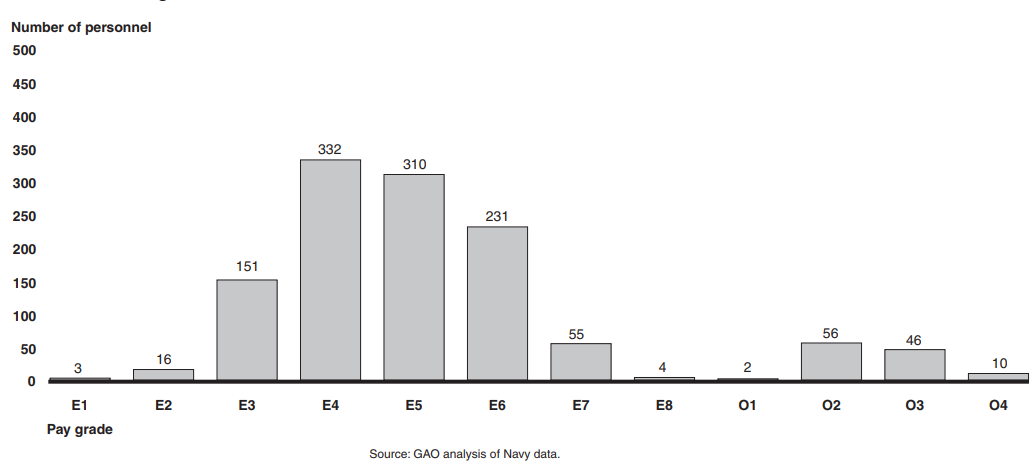

The Navy had to make its own retraining adaptations. The Individual Augmentee (IA) program pulled Sailors from assignments that usually took them to sea and instead deployed them to serve in augmented roles on land. However, the numbers were very uneven across the Navy’s various communities. Even though tens of thousands of Sailors deployed through the IA program it appears less than five percent of Navy individual augmentees came from the surface fleet.4 This points to a major difference in how the Navy adapted to counterinsurgency compared to the other services, in that even in a time of insurgent war the Navy still continued to operate less relevant force structure at pre-9/11 levels. The Navy never went so far as the Army or Marines who regularly made their armor and artillery units leave their main weapons behind. The Navy’s ship deployment rate went unaffected by any augmentation or retraining.

The diminished relevance of blue water naval power in the Global War on Terror is reflected in the work of Lieutenant Commander Alan Worthy, who interviewed numerous Sailors while researching the Navy’s IA program:

“A significant number of the young Sailors I spoke with joined the Navy specifically to be part of this ongoing war. They joined after 9/11 or after the GWOT began and wanted to get into the fight. In my interviews, I was surprised to learn that a considerable percentage of Sailors did not have a good understanding of the Navy’s role in the GWOT. For Sailors who were in the Navy before the war, their day-to-day duties out to sea had not significantly changed because of the war. For those who joined to fight this war, it has been difficult to see what their daily efforts out to sea were accomplishing. The strategic effects of missions such as maritime dominance and theater security cooperation are often unrealized by the average Sailor as they go about daily sea life. Unlike Marine Corps and Army accomplishments, which are in the daily news media, Sailors do not regularly get to the opportunity to see or hear how the maritime mission directly contributes to the war.”5

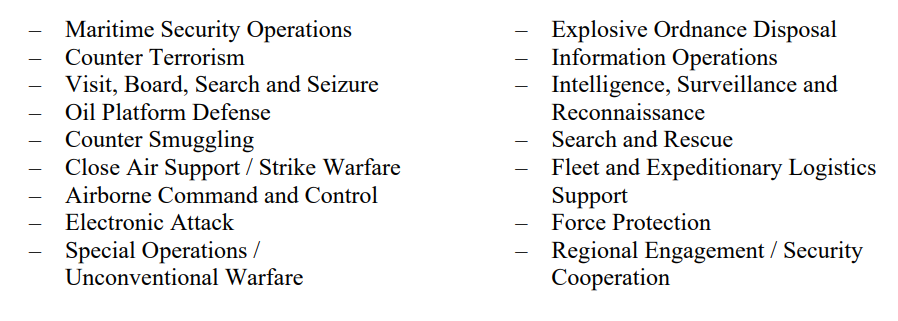

The Navy was poorly suited to counterinsurgency, forcing it to focus its operational energies elsewhere. The low-end spectrum missions opened up many opportunities to conduct diverse operations that would allow the Navy to put the forward presence of its ships to use. Warships conducted missions such as counterpiracy, maritime security, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Ships protected fisheries, caught smugglers, and taught foreign counterparts how to better provide for their own security. Partnership engagements in particular became a leading operational activity for U.S. naval power as concepts such as the 1,000-ship Navy and Global Fleet Station urged greater international cooperation.

The power projection era ushered in what may be remembered as a high time for naval soft power, where the Navy devoted a significant amount of its time and skill on directly helping other nations improve their human condition. However, many of these operations are better described as opportunities offered by the diverse set of missions found at the low-end spectrum of operations, rather than pressing requirements driven by wartime demand. While tens of thousands of Soldiers and Marines were solely focused on advising heavily embattled Iraqi and Afghan counterparts the Navy enjoyed the luxury of frequently partnering with dozens of other nations, almost all of whom were not engaged in any major hostilities.

Despite these low-end missions the Navy’s stringent level of continuous forward presence was mainly for guaranteeing deterrence by denial. The Navy sought to primarily deter Iran, who was perfectly positioned to interfere with the Strait of Hormuz and threaten one of the most important global energy lifelines. Iran has regularly made outspoken threats to close the Strait, has far more naval forces than its Arab rivals, and attacks on international shipping in the 1980s prompted armed U.S. intervention that targeted Iranian assets. By continuously maintaining a carrier strike group in the Middle East the Navy sought to insure the global economy and regional allies against Iran.

The necessity of this demanding level of presence is questionable. Unlike in Europe or Asia, the conventional military balance in the Middle East favors U.S. allies versus Iran. The past two U.S. administrations have given tens of billions of dollars’ worth of advanced military aid to U.S. allies in the region, especially those that are staunch rivals of Iran such as Gulf Cooperation Council states and Israel. While Iran certainly enjoyed some military advantages during the power projection era its temptations to pursue major military action may have been tempered by the tens of thousands troops the U.S. deployed to countries flanking Iran.

The worldwide significance of the seaborne energy that transits the Persian Gulf is perhaps the best security guarantor. Iran could cause global economic damage if it tried to close the Strait or initiate major war with its regional rivals, but this would likely prompt extremely fierce condemnation from across the world. Even if the U.S. Navy couldn’t instantly respond, the overriding factor of politics would likely be on its side. With the advantages of politics and allies, deterrence by denial against a rogue state is less necessary if a superior coalition can be counted on to surge in response. Iran’s ability to close the Strait militarily is highly doubtful, but the possibility of this prompting an internationally-supported counter-intervention is not. The same cannot be said for how the world would respond to many contingencies involving great power war.

The Navy struggled to find a place for itself in the power projection era, but it would not abandon its traditional ship deployment rates as major land wars broke out in the Middle East. Instead, it reacted to a new national security focus by subscribing to questionable logic. During this time the Navy chose to obsessively overspend its readiness on many missions that are completely optional in nature, and on a level of deterrence that was hardly warranted. Yet the Navy was so convinced of the necessity of these operations that for years it willingly sacrificed its material readiness, tolerated severe maintenance troubles, and let its warfighting competence wither away.

This unrelenting insistence on optional missions and a total disregard for full-spectrum competence produced decades of fleet deployments that were driven by a grossly misplaced sense of urgency. In a time of power projection and insurgent wars, if any branch of the military could have safely made time to prepare for the high-end fight, it is the Navy.

Full-Spectrum Competence and U.S. Naval Power

“With the demise of the Soviet Union, the free nations of the world claim preeminent control of the seas and ensure freedom of commercial maritime passage. As a result, our national maritime policies can afford to de-emphasize efforts in some naval warfare areas. But the challenge is much more complex…We must structure a fundamentally different naval force to respond to strategic demands, and that new force must be sufficiently flexible and powerful to satisfy enduring national security requirements.” –…From the Sea: Preparing the Naval Service for the 21st Century (1992)

With the downfall of the Soviet Union the U.S. Navy could afford to take a step back from high-end warfighting. But a single-minded focus on the low-end fight or heavily scripted training could hardly be justified even with the demise of a great power competitor. Difficult threats remained, and required that the Navy still retain high-end warfighting skills. The failure to maintain full-spectrum competence during the immediate post Cold-War era could now come home to roost with the rapid onset of great power competition in maritime Asia.

The Navy allowed the low-end skillset to dominate the nature of its pre-deployment training, but full-spectrum competence across the range of missions is no option for a Navy tasked with protecting the global interests of a superpower. A ship could be conducting counterpiracy operations one week and conducting a show of force near a missile-armed state the next. Ships en route to the Middle East can pass through the South China Sea and be shadowed by the Chinese Navy. Warships in the Mediterranean could be helping refugees stranded in the ocean while a Russian squadron hangs over the horizon.

The power projection era sought to shift the Navy’s attention to littorals mostly populated by third-world states, but these areas contain no shortage of powerful capabilities and tactical challenges. Iran for example still fields a respectable amount of conventional military capability such as coastal anti-ship missile batteries, fast attack craft, mines, and Russian-made submarines. While the quality and resilience of the Iranian military is questionable in many respects, it is still a multi-domain threat worthy of consideration.

The credibility of littoral threats was already recognized in key strategy papers that announced the Navy’s power projection focus. As the major Navy strategy document …From the Sea (1992) declared “a fundamental shift away from open-ocean warfighting on the sea toward joint operations conducted from the sea” it also recognized that this different operating environment of the littoral still had no shortage of tactical challenges:

“The littoral region is frequently characterized by confined and congested water and air space…making identification profoundly difficult. This environment poses varying technical and tactical challenges to Naval Forces. It is an area where our adversaries can concentrate and layer their defenses. In an era when arms proliferation means some third world countries possess sophisticated weaponry, there is a wide range of potential challenges…an adversary’s submarines operating in shallow waters pose a particular challenge to Naval Forces. Similarly, coastal missile batteries can be positioned to ‘hide’ from radar coverage. Some littoral threats–specifically mines, sea-skimming cruise missiles, and tactical ballistic missiles–tax the capabilities of our current systems and force structure. Mastery of the littoral should not be presumed.”6

The power projection focus still required strong warfighting skills, and could hardly justify scripted training or a lack of attention to high-end warfighting. Perhaps the terms “littoral” and “power projection” somehow became synonymous with “easy” for the U.S. Navy, and allowed it to atrophy its warfighting skills.

Even with the demise of the Soviet Union the Navy still had an obligation to deter powerful states. This was made especially clear in one of the most high-profile shows of force in the power projection era when the U.S. deployed carrier battle groups to deter China during the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis. This event added urgency to China’s desire to modernize its military for high-end warfighting, but apparently it did little to remind the U.S. Navy of its obligations toward full-spectrum deterrence.7

Perhaps the neglect of full-spectrum competence was built on the assumption that the Navy could easily regenerate high-end skills if a new great power rival presented itself. The Chinese Navy has been given an opportunity to test this assumption. The Chinese Navy’s push for high-end competence overlaps with the American Navy’s generational focus on low-end missions, suggesting the PLAN has stolen a march on the U.S. Navy with respect to high-end force development.

After the Soviet Union fell the U.S. Navy could have taken a different path. The lack of utility of blue water naval power for counterinsurgency could have been a blessing in disguise for the Navy while the other services were heavily tied down by operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. During the power projection era the Navy could have focused on settling complex developmental questions posed by Information Age technologies, and evolved its high-end skills. The Navy effectively missed a historic opportunity to make major progress on force development, where the fleet could have easily focused on securing its future dominance. Instead, it let a rising rival close the gap.

For a generation the Chinese and U.S. Navies have focused their skills and culture on opposite ends of the warfighting spectrum, and this disparity is far more fatal to the American fleet. A superpower navy does not threaten itself by lacking low-end skills, but it can certainly risk its defeat and destruction by failing to be ready for the high-end fight. The Navy assumed great risk by failing to maintain full-spectrum competence while an authoritarian China rose to become both a superpower and a maritime power. A possible historical legacy of the likes of Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden could now include helping the U.S. Navy atrophy to such a degree that its decay was taken advantage of by an ascendant great power rival.

Matching Exercises to Strategy

“A final way in which the Maritime Strategy has served as a focus for reform is by shaping an emphasis on tactics and warfighting at the operational level. For too many years, our fleet exercises suffered from a lack of realism and focus, and our routine operations seemed to be lacking in purpose. But the Maritime Strategy now forms a framework for planning realistic, purposeful exercises, and provides a strategic perspective for daily fleet operations in pursuit of deterrence.” –Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James Watkins on the 1986 Maritime Strategy

The low-end skillset clearly proved its worth. Navy Special Forces took out numerous insurgent leaders, collected valuable intelligence, and conducted sensitive operations worldwide. Sailors helped save thousands of lives in the wake of environmental disasters like the deadly tsunamis in Asia and after Hurricane Katrina at home. These low-end missions elevated the Navy’s role in many respects by applying naval power to a greater variety of problems and with many partners. These missions developed meaningful relationships around the globe, and were an excellent opportunity to put national values into practice abroad. The skills and relationships that come with low-end missions will remain relevant going forward because great power competition is still whole-of-government competition in peacetime and in war.

But after the fall of the Soviet Union the U.S. Navy did not just double down on these missions, it went all in. High-end warfighting experience barely came from either the Navy’s training or its forward operations. Of the little time that was actually spent on events that approached high-end exercising, few were truly challenging or well-connected to force development because of heavy scripting. Properly resourced force development can still be undercut by heavy scripting, and quality exercises can still be starved of ready units. In the Navy’s case, high-end force development was effectively taken off the schedule and out of its strategy through a self-inflicted lack of both resourcing and standards.

There is not a stark tradeoff between deterrence, force development exercising, and forward presence because of naval power’s mobility. The Navy can easily exercise within the depths of the Indian, Atlantic, or Pacific Oceans and still remain on call to respond to a contingency within days. This mobility allows for a more remote operating posture to still count as forward presence for the sake of deterrence. However, it would not be the sort of upfront presence that supports the type of small-scale exercises that come with most low-end missions. The Navy did not add more forward presence by deploying the usual 100 ships per year, but rather by disaggregating its formations once they came on station to better take advantage of the many opportunities that come with the low-end focus. By often making formations disaggregate themselves within the forward-most littorals the Navy optimized its presence to exercise for partnerships and low-end operations, rather than stronger deterrence and force development.8

The unbalanced logic of focusing solely on low-end missions caused the Navy to operate with far fewer constraints. Concepts of presence, overseas partnership, and undersea surveillance can become boundless and open-ended, where a force can quickly overwhelm itself with the many opportunities that come with these missions. In a well-rounded strategy these missions would be heavily constrained by training and force development requirements alone, where adequate time for force development has to be protected against many other demands. Trying to maintain high levels of continuous forward presence with a shrinking fleet made it difficult to maintain larger formations without disrupting schedules. A strained readiness cycle and a tunnel-vision focus on low-end missions combined to stretch the fleet so thin that it could rarely get enough ships together to properly resource high-end force development with large exercises.

The Navy can look to what other military branches have done for decades. The Army sends about a third of its brigades every year to the National Training Center, and hundreds of aircraft participate each year in the Air Force’s Red Flag exercises.9 Other military services know that they must guarantee a significant amount of readiness for large-scale exercises.

The Navy still conducted numerous training exercises every year, but their chronic lack of true opposition deprived them of value. The Army and Air Force know to dedicate units to act as full-time opposition forces (OPFOR), to empower those units to inflict meaningful losses, and to mandate them to master the methods of rivals. The Army’s major OPFOR unit is the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, and for the Air Force it is the 57th Adversary Tactics Group. By comparison the Navy has no dedicated OPFOR warship formations.

OPFOR units are among the most proficient units in the armed forces because their primary mandate is to train hard, they are given plenty of opportunity to do so through large-scale events, and they are well-connected to an extensive learning architecture that is built around their exercises. People serving in dedicated OPFOR units can take unique culture, tactical knowledge, and professional connections with them throughout their careers. Dedicated OPFOR units perform a strategic force development function by acting as incubators from where tactical excellence can spread throughout the force.

Dedicated OPFOR units are also indispensable because superpowers often think about warfighting in widely different ways. Capt. Dale Rielage (ret.), who wields an intelligence background specializing in China and experience leading opposing forces as the senior member of the Pacific Naval Aggressor Team, sheds light on how the U.S. and Chinese Navies have significant conceptual differences in the conduct of war:

“The Marxist-Leninist view of warfare focuses on military science where Western practitioners focus on military art, which creates an objective analytic approach to warfare. While the PLA has developed and adapted Marxist thinking in the almost century since the first Soviet instructors arrived, it still defines its basic approach to warfare as a ‘Marxist view of strategy with Chinese characteristics.’ The result is that the PLAN, like its Soviets predecessors, practices a style of warfare heavily based on what Westerners would call operations research. This focus has a real impact on PLAN forces and doctrine. For example, the belief that warfare has complex but discernible rules likely produces a military more accepting of automating command functions.”10

Conceptual differences in the conduct of war can lead to highly dissimilar tactics and operational plans, which complicates training realism. Regular troops that are asked to act as opposition forces on short notice can quickly fall into mirror-imaging, where by training and instinct they can easily default to their own nation’s way of war. A rival’s view on the conduct of war can be so complex and different that it warrants dedicated units to fully understand it, train to it, and then put that alternate vision of warfighting into practice. By applying a rival’s tactics a dedicated OPFOR unit can reveal how different warfighting methods could clash with one another to produce unique combat dynamics. This is necessary for defining realism, and to know how one stacks up against the enemy’s way of war is a question of the highest strategic importance.

Now in an era dominated by great power competition even more attention must be devoted to exercising for the high-end fight beyond the responsible minimum needed for full-spectrum competence. But as a result of a long overemphasis on low-end missions the budgets and operating norms of the fleet were stretched to their limits in the absence of a major demand signal. The result is a Navy that must dig deeply into its own time and pockets to make painful choices to correct itself.

Exercises as the Link Between Tactics and Strategy

“In the past tactics has suffered from lack of standard instructions, lack of records, lack of planning and tests of efficiency, lack of a ‘home office’ in the Department, but most of all it has suffered from lack of time in the fleet schedules…The tactical training of our fleet for war has suffered in the past, is now suffering, and will continue to suffer because of the ‘tight’ schedules of the present system.” –Commander Russell Wilson, “Our System of Fleet Training,” April 1925.

Regardless of their immense value exercises still cannot answer plenty of important questions. Exercises cannot probe many of the larger strategic concerns that can inform a campaign, such as political considerations or industrial base limits. These broader questions are more readily assessed using analysis and simulations rather than through the maneuvers of live units. Instead, where realistic combat exercises find their place in strategy is in how they dominate the realm of tactics, and how tactical-level success is the foundation of winning strategy.

Knowing how to organize for tactical success is critical toward crafting strategic plans, and Clausewitz proclaimed that proper strategy is completely contingent on superior tactics:

“…endeavor above all to be tactically superior, in order to upset the enemy’s strategic planning. The latter [strategic planning], therefore, can never be considered as something independent: it can only become valid when one has reason to be confident of tactical success…let us recall that a general such as Bonaparte could ruthlessly cut through all his enemies’ strategic plans in search of battle, because he seldom doubted the battle’s outcome…all strategic planning rests on tactical success alone…this is in all cases the actual fundamental basis for the decision.”11

Failing to understand surprise at the tactical level will eventually beckon surprise at the strategic level because one cannot be too sure of knowing if they can win if they are not sure how to win. Tactical shortsightedness can not only come from a lack of warfighting competence, it can also come from a poor understanding on how capability trends have evolved to redefine tactical ground truth. The unforseen tactical carnage wrought by the machine gun, trench, and artillery barrage in WWI was so devastating it shattered strategic concepts on both sides.12

Exercises come closest to real fighting because only they can use live units to create mock battles, making them the most important activity for understanding the tactical level of war. Only exercises can help thousands of troops practice tactics, and only exercises offer troops the most realistic proving grounds for testing tactical ideas. After having experimented enough to discover the tactical truths that govern the conduct of future war, and after having inculcated the related tactics into the force, exercises can also then be used to reveal tactical skill through bold maneuvers and rehearsals.

Exercises are the best possible means to teach tactics through training, to invent tactics through experimentation, and to showcase tactics for deterrence through demonstration. To strongly emphasize challenging exercises is to pay appropriate respect to how the tactical level of war is the foundation upon which strategy rests.

Hazarding a Navy, a Maritime Nation, and a Maritime System

“If in the future we have war, it will almost certainly come because of some action, or lack of action, on our part in the way of refusing to accept responsibilities at the proper time, or failing to prepare for war when war does not threaten. An ignoble peace is even worse than an unsuccessful war…” –Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, 1897

A generation’s worth of poor priorities and standards has gambled much of the Navy’s credibility away. Readiness is degraded across the board, from the material state of the ships, to the warfighting competence of the individual Sailor, and to the level of institutional understanding of high-end warfighting. This degraded sea control capability can pose a strategic liability, especially when a rival superpower is focused on creating a powerful sea control capability of its own. The history of the United States and its chosen role of advancing a principled global order points to what the U.S. and the rest of the world stands to lose from an American Navy deficient in sea control.

The discovery and colonization of the New World was driven by maritime power. Wave after wave of ships delivered settlers, supplies, and influence as the great maritime powers of the time such as Great Britain and Spain sought to expand and compete across a new hemisphere. Here the United States finds its origin story as a colony of a maritime superpower, a nation whose founding was made possible by the sea.

After gaining independence from Great Britain the United States gained a similar sort of strategic flexibility its English forefathers enjoyed. Nations in most other continents border several neighbors which forces them to always be aware and engaged. As a maritime nation, the United States could often choose to use the large oceans that divide it from most of the world to keep its distance from international events, or actively engage abroad if desired. This relative isolation from international turbulence helped the United States bide its time on developing itself into a first rate power. Soon after the start of the 20th century the U.S. had gained enough in confidence and strength, and announced its ascendancy as a nation of global influence in part through a high-profile naval deployment in the form of the Great White Fleet.

The independence that often came with being a maritime nation is gone today. The world’s oceans have become an even more indispensable foundation for human progress and globalization. By far the most cost effective form of transportation, 90 percent of the world’s trade goes by sea.13 2.4 billion people, a third of the world’s population, live within 60 miles of a coast.14 97 percent of global communications and $10 trillion in daily transactions flow through undersea cables.15 International benefits and problems can be more readily transferred through the seas, and severe shocks to the maritime system can quickly cascade throughout the global economy.

In a war at sea these things that make the world’s oceans a pillar of civilization become pressure points at the mercy of the victorious navy. By projecting power through the air, surface, subsurface, and across the coastline blue water naval power can dictate foreboding terms through sea control. The consequences of command of the seas are especially more severe for maritime nations such as the United States, where being isolated by the sea comes with greater dependence on it. A powerful example comes from the U.S. Navy’s own history in dominating the navy of a maritime superpower in WWII. It is a curious thing that several of the Navy’s top admirals came out against dropping the atom bomb when their proposals to end the war included using uncontested sea control to starve millions of Japanese into submission.16

A maritime nation that is separated from its allies by oceans requires sea control to send reinforcements abroad and maintain physical links, making the Navy especially critical to American security guarantees. The U.S. Navy could easily serve as the tip of the spear for the rest of the American military in many contingencies, since “Control of the seas near land assures the prompt access and freedom of maneuver of joint forces from the sea base.”17 The U.S. Navy must be able to secure forward spaces and sea lanes well enough to allow the joint force to surge across the ocean from the homeland. If the Navy cedes sea control to a superpower rival many U.S. allies could be left to fend for themselves.

Maritime commerce could be interdicted by a hostile Navy, causing untold economic damage and offering a powerful point of leverage. Coastlines and territories could be threatened by amphibious invasion. Population centers and critical infrastructure could be attacked deep inland through long-range fires safely delivered by ships at a distance. If the U.S. Navy cannot best a great power rival at sea control then many allies would be put at the mercy of the same sort of blue water naval power the Navy itself has wielded for decades.

The value of American naval supremacy goes far beyond what it could offer in war because of the nature of the global maritime system. Command of the seas is not just a wartime state of dominance for a particular Navy or coalition. It can also be understood as a particular state of peace. Today, command of the seas does not belong to any one nation or group, but rather it belongs to all as a global commons.

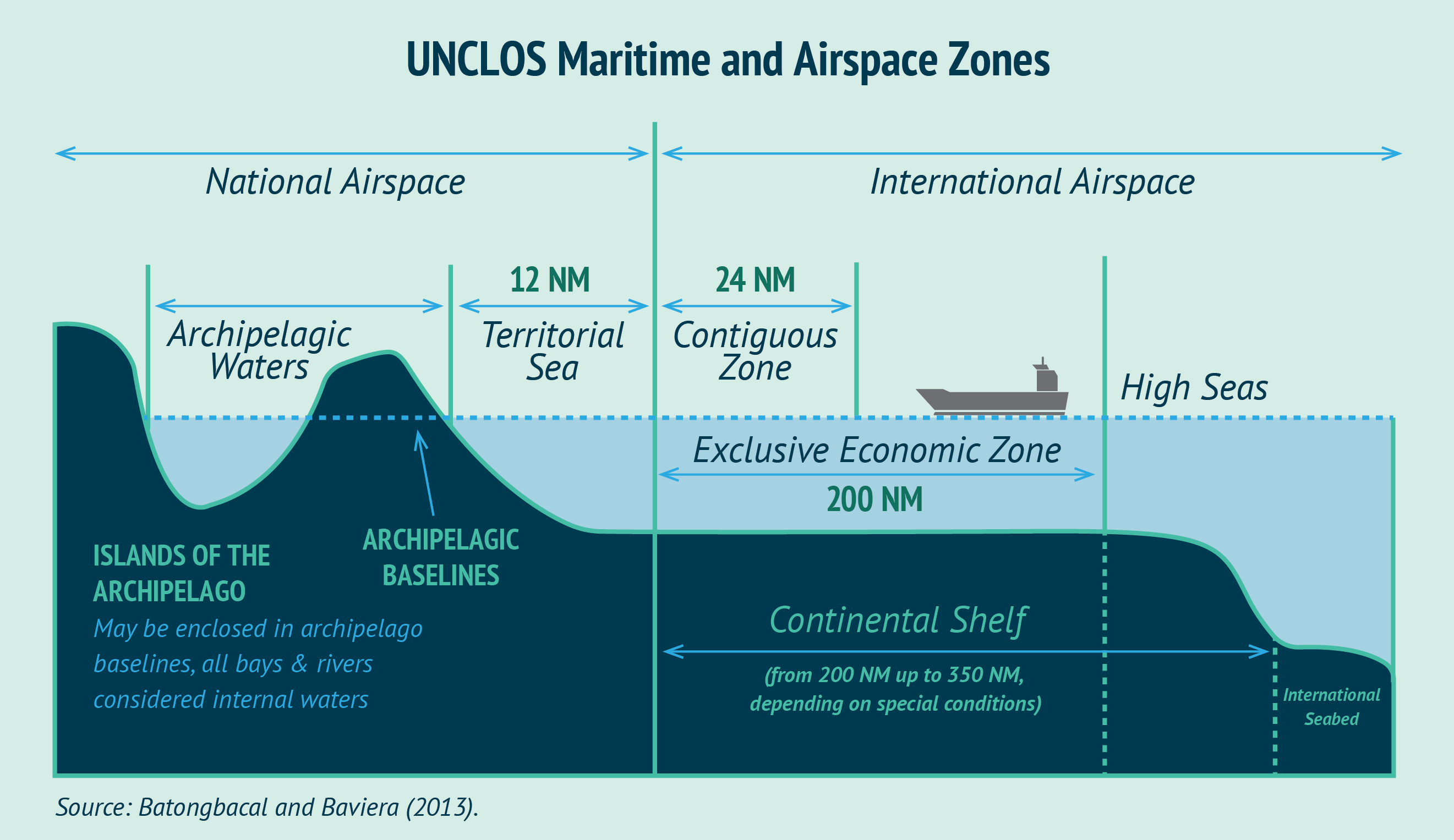

The set of rules that govern the world’s oceans was not solely decided by the world’s strongest powers, nor does it vary from region to region based on local preferences. In this sense, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a historic human achievement. It lays down rights and rules for most of the surface of the world with regard to safe passage, economic development, and many other legal matters for conduct within the global maritime domain. 167 countries have ratified UNCLOS, including China.

The U.S. hasn’t ratified UNCLOS, but still adheres to many of its provisions as customary international law.18 The commitment to a common and principled legal framework to guide conduct on the world’s oceans is perhaps one of the more high-profile examples of American commitment to a rules-based international order. The United States has repeatedly demonstrated its seriousness about protecting the principle of freedom of navigation, with the U.S. Navy being a main instrument for doing so.

A Freedom of Navigation Operation conducted by U.S. warships is not simply a message to highlight the violation of rules or norms. It is the American Navy retracing a red line the United States has a long history of enforcing through the use of force. From Barbary pirates to the impressment of Sailors, to Gaddafi’s “Line of Death” or the Tanker Wars in the Persian Gulf, freedom of navigation has figured prominently in U.S. military intervention for over two centuries.19

On the other hand, China’s commitment to undermining the rules of the global maritime system is one of its most brazen examples of contempt for international order. Trillions of dollars of trade flow through the South China Sea since it is the main body of water that most seaborne commerce from Africa, Europe, and the Middle East transits on the way to Asia. China’s claim to the whole of the South China Sea is a clear example of a nation viewing its personal sense of entitlement as more important than respecting an agreed-upon framework of conduct that was forged by global cooperation. It remained steadfast in its selfish defiance even after its claims were decisively ruled against by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea at The Hague.

China’s worsening authoritarian character and the rapid ascent of its powerful Navy casts doubt on its maritime ambitions. If China wins command of the seas through war or other means it could earn a powerful medium for peacetime coercion by molding the maritime commons to its advantage. What would be the character and norms of such an authoritarian maritime system? Given the interconnected nature of the world’s oceans, command of the seas in a specific region could be enough to exert targeted pressure on a global scale. But how could an authoritarian state impose and enforce such a vision? Defeating the U.S. Navy would certainly go a long way.

Part 7 will focus on Strategy and Force Development.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

References

1. Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “U.S. deploying heavily armored battle tanks for first time in Afghan war,” Washington Post, November 19, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/11/18/AR2010111806856.html?noredirect=on

Robert S. Cameron, Armor In Battle, U.S. Army Center of Military History, August 2016. https://history.army.mil/news/2016/images/gal_armorInBattle/Armor%20in%20Battle_opt.pdf#page=480

2. Major Daniel C. Gibson, USA, “Counter-Insurgency’s Effects on the U.S. Army Field Artillery,” USMC Command and Staff College Marine Corps University, 2010. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a602988.pdf

Boyd L. Dastrup, “Artillery Strong: Modernizing the Field Artillery for the 21st Century,” Combat Studies Institute Press, 2018. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/combat-studies-institute/csi-books/Artillery-Strong-Final.pdf

Excerpt: “Redesigning the school’s curriculum went beyond modernizing the 2005–2006 Field Artillery Captain’s Career Course under Colonel McDonald. With the 2003 rise of the insurgency in Iraq, field artillery Soldiers devoted the bulk of their time to nonstandard missions, such as patrolling, providing base defense, and convoy operations. Because only a few field artillery units provided fire support, field artillery core competencies atrophied. As outlined in the 20 July 2006 Army Campaign Plan Update, the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, General Richard A. Cody, understood the effect of nonstandard missions. He directed the US Army Training and Doctrine Command to assess the competency of field artillery lieutenants to determine if nonstandard missions in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom had degraded their basic branch skills and if they required additional or refresher training.”

3. Naval History and Heritage Command, “Where Are the Shooters? A History of the Tomahawk in Combat,” 2017. https://www.public.navy.mil/surfor/swmag/Pages/Where-are-the-Shooters.aspx

4. Government Accountability Office, “Military Readiness: Navy Needs to Reassess its Metrics and Assumptions for Ship Crewing Requirements and Training,” June 2010. https://www.gao.gov/assets/310/305282.pdf

5. Lieutenant Commander Alan Worthy, “U.S. Navy Individual Augmentee Program: Is it the Correct Approach to GWOT Service?” Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps University, 2008. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a490401.pdf

6. Department of the Navy, …From the Sea: Preparing the Naval Service for the 21st Century, September 1992. https://www.navy.mil/navydata/policy/fromsea/fromsea.txt

7. Michael Chase et. al, China’s Incomplete Military Transformation: Assessing the Weaknesses of the People’s Liberation Army, RAND, 2015. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR893/RAND_RR893.pdf

8. For disaggregation norms see:

Naval Operations Concept 2010. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/noc2010.pdf

Carrier Strike Group 11 Fact Sheet. https://www.public.navy.mil/surfor/ccsg11/Documents/FactSheet.pdf

9. For National Training Center reference:

Colonel John D. Rosenberger, “Reaching Our Army’s Full Combat Potential in the 21st Century: Insights from the National Training Center’s Opposing Force,” Institute of Land Warfare, February 1999, https://www.ausa.org/

Major John F. Antal, “OPFOR: Prerequisite to Victory,” Institute of Land Warfare, May 1993. https://www.ausa.org/

For Red Flag Reference:

414th Combat Squadron Training “Red Flag,” July 2012. https://www.nellis.af.

10. Capt. Dale Rielage, USN (ret.), “The Chinese Navy’s Missing Years,” Naval History Magazine, December 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/navalhistory/2018-12/chinese-navys-missing-years

11. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret.

12. Hew Strachan, “The Strategic Consequences of the World War,” The American Interest, June 2, 2014. https://www.the-american-interest.com/2014/06/02/the-strategic-consequences-of-the-world-war/

13. IMO Profile, International Maritime Organization, United Nations Business Action Hub. https://business.un.org/en/entities/13

14. NASA “Living Ocean.” https://science.nasa.gov/earth-science/oceanography/living-ocean

15. Brandon Knapp, “How Exposed Deep-Sea Cables Could Leave the Economy Vulnerable to a Russian Attack,” C4ISRnet, February 1, 2018. https://www.c4isrnet.com/it-networks/2018/02/01/how-exposed-deep-sea-cables-could-leave-the-economy-vulnerable-to-a-russian-attack/

16. Jim Hornfischer, The Fleet at Flood Tide, Bantam, 2016.

17. Department of the Navy, Naval Transformation Roadmap, Power and Access…From the Sea, 2002. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/b295445.pdf

18. Steven Groves, “Accession to the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea Is Unnecessary to Secure U.S. Navigational Rights and Freedoms,” Heritage Foundation, August 24, 2011. https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/accession-the-un-convention-the-law-the-sea-unnecessary-secure-us-navigational

19. James Kraska, “The Struggle for Law

in the South China Sea,” Statement of Professor James Kraska Before the Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, September 21, 2016. https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS28/20160921/105309/HHRG-114-AS28-Wstate-KraskaSJDJ-20160921.pdf

SUEZ CANAL, Egypt(Sept. 23, 2008) The amphibious transport dock ship USS San Antonio (LPD 17) transits through the Suez Canal. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jason R. Zalasky (Released)

The author implies that the Navy’s role in OIF/OEF was limited to “low-end” engagements. It is true that the Navy has not been significantly challenged at sea by a near-peer competitor in decades. However, one of the reasons Navy resources have been stretched so thin since 9/11 is force employment in direct support of OIF/OEF (the era of long-extended deployments and long-deferred maintenance). Certainly as late as 2011/2012, one and often two aircraft carriers were still supporting round-the-clock air sorties in support of OEF. Multiple vessels were forward-deployed in active-tracking BMD roles, and supervising Navy & CG PBs defending oil platforms, including against deadly attacks such as the one in 2004. Just as the Army left its tanks behind, the Marines left their Navy amphibs behind, and were heavily engaged in both OIF/OEF. Additionally, the forward-deployed Navy strike groups, particularly in 5th Fleet, conducted constant, daily drills and training involving all warfare areas simultaneously.

For a number of years in the past two decades, the Navy has taken a leading role in securing transit corridors through the Gulf of Aden to allow the safe passage of maritime commerce – a key component of sea control.

The entire concept of a strike group may be outdated in the 21st century of autonomous vessels/aircraft and cyberwarfare; certainly it poses a risk to concentrate one’s capital ships in such an obvious way – there’s no hiding from global satellite coverage. Once “on station,” in peacetime or low-conflict areas of the world, after conducting ongoing war games for weeks of a deployment, it makes sense to assign the ships to a variety of productive missions – including exercises to strengthen interoperability with allies.

This does not even begin to address the role of SSBNs over the past 30 years.

Recent Navy deployments and workups have involved “Red Cells” with a good deal of freeplay autonomy.

An argument certainly can be made that exercises, training, funding, and perhaps SecDef deployment decisions in support of the 17+ year GWOT were misguided, especially looking in hindsight. However, it is inaccurate to state that the Navy has only conducted low-end operations for the past 20 years. If the Navy has “forgotten how to fight,” it is largely because they have not been significantly challenged at sea in some time. Fighting a simulated enemy will never generate the same energy as against a real one. Nor do we know what the next fight will look like – though almost certainly not a large Mahanian sea battle. More aggressive Red Teaming is perhaps the best option to keep the trident sharp before the next naval conflict rears its ugly head.