By Dr. Salvatore R. Mercogliano

COVID and the Straining Merchant Marine

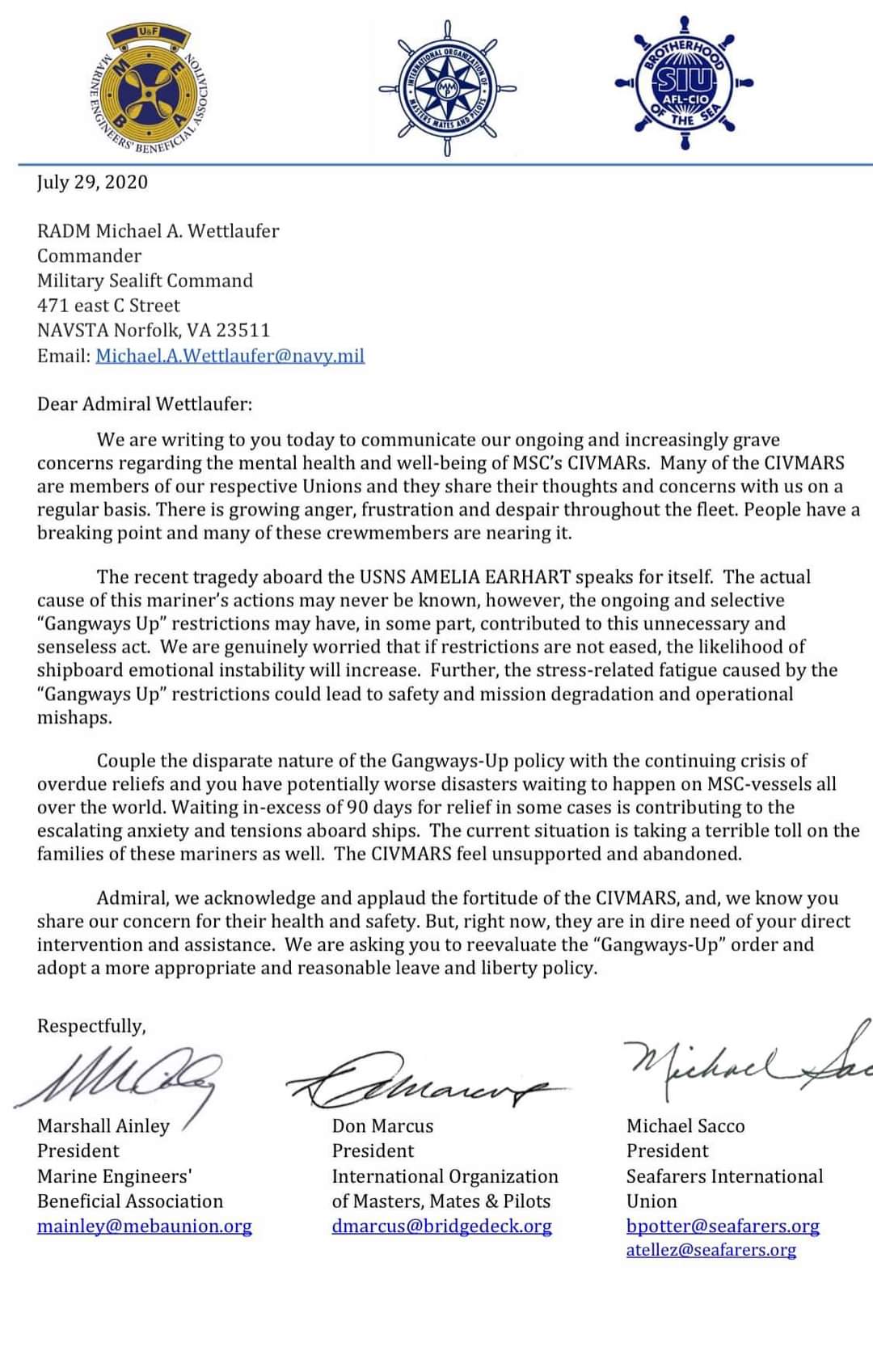

On July 29, 2020, the heads of three maritime unions – Marshall Ainley of the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association, Don Marcus from the International Organization of Masters, Mate & Pilots, and Michael Sacco, the long-time President of Seafarers International Union – jointly penned a letter to Rear Admiral Michael A. Wettlaufer, the Commander of the U.S. Navy’s Military Sealift Command. In their one-page letter, they were blunt and to the point: “We are writing to you today to communicate our ongoing and increasingly grave concerns regarding the mental health and well-being of MSC’s CIVMARS [civilian mariners].”

They highlighted three specific issue. First, the March 21, 2020 “Gangway Up” order that restricted merchant mariners to their ships due to the COVID-19 outbreak. While the act was prudent and ensured the readiness of the vessels to respond to missions, it was done with no warning and more importantly, did not apply to naval personnel assigned to the vessels or contractors. Therefore, the quarantine intended to be in place on board ship was broken daily, while crewmembers who reported on board for work that morning found themselves trapped and threatened with termination if they left the vessel, while others moved freely on and off the ship. This became apparent with a breakout on board USNS Leroy Grumman undergoing a yard availability in Boston.

The second issue involved the recent tragedy on board USNS Amelia Earhart. On July 22, third officer Jonathon J. Morris of San Mateo, CA fatally shot himself on board. The letter from the three union heads noted, “the ongoing and selective ‘Gangways Up’ restriction may have, in some part, contributed to the unnecessary and senseless act.”’ While there is no evidence to indicate this, my personal communications with crewmembers on board Amelia Earhart indicate that the event has not triggered any change in the operation of the vessel. While counselors were sent to the ship, its operations continue with no safety stand down, and not even a chaplain accompanied the vessel as it sailed to perform services for the fleet with some of the mariners not setting foot on ground for almost a half a year, except to remove the body of their shipmate. Mariners remained restricted to the ship in port, while active duty Navy personnel left the vessel.

The final issue is the delay in reliefs for crews, up to 90 days late in some cases. Many mariners have not been home since the COVID-19 outbreak hit the United States or were permitted ashore in that time period. MSC’s leave policy for its mariners is well outside the norms of common maritime industry practice because mariners hired directly by MSC must conform to government employment rules, even though they operate in an environment completely different than the normal federal employee. Mariners earn a set number of hours of leave every two weeks. The only addition is 14 days of annual shore leave. For new employees to MSC, this means 10 months onboard ship (tours are usually limited to four months, but delays are typical) and only two on land in a year.

While shore-side government workers enjoy flex work schedules, weekends at home, get holidays off, enjoy the occasional snow day, and can schedule vacations well in advance, MSC mariners are toiling at least eight hours a day, seven days a week for a minimum of four months at a time when wages are comparable to those ashore. They miss weekends, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries, events with children, and now they face prolonged wait for relief. Unlike Navy sailors, MSC mariners do not rotate to shore billets or have many of the opportunities for education and training afforded to naval personnel. Even worse, those waiting to get out to ships have used all their leave and are now ashore, considered absent without leave, and not being paid as they await a call to report back to work for a potential assignment out to the fleet.

This is the situation facing 5,383 MSC mariners who crew 20 percent of the 301 ships in the U.S. Navy. Let that number sink in for a moment: one out of every five ships in the battle force of the U.S. Navy is crewed by merchant mariners and not U.S. Navy sailors. All 29 of the auxiliary supply ships, the dozen fast transport ships, and the fleet tugs and salvage ships are all operated and commanded by merchant mariners. Some ships, such as the submarine tenders, command ships, and expeditionary support bases, while commanded by a naval officer, have merchant mariners who operate the deck, engine, and steward departments on board. This does not include the fleet of contract operated vessels in the afloat prepositioning force, sonar surveillance, ocean survey or sealift vessels with another 1,400 contract merchant mariners.

Yet these recent issues facing the Merchant Marine are not simply the product of COVID or other recent events. They are simply yet another expression of the longstanding problems of status the Merchant Marine has faced within the U.S. Navy.

Inequality in the Merchant Marine

Throughout the U.S. Navy, specialized communities are commanded by one of their own – submariners command submarines, aviators command squadrons and carriers, SEALs command special operations, and so forth. Yet, when it comes to merchant mariners, they fall under the command of serving U.S. naval officers with little to no experience with merchant mariners.

Recently, MSC had two commanders – Mark Buzby and T. K. Shannon who graduated from merchant marine academies and were at least familiar with the U.S. merchant marine. The last two MSC commanders – Dee Mewbourne and Michael Wettlaufer – are both aviators. In the past, non-surface warfare commanders have done exceedingly well, particularly two submariners – Glynn Donaho and Lawson Ramage. They oversaw MSC’s forerunner – Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS) – during the Vietnam era, when the service handled mainly passengers, cargo, and fuel and they were experts in disrupting those services due to their experience with sinking the Japanese merchant marine in the Second World War.

Today, MSC is integrated into the fleet structure and many of its previous sealift missions are shared with the Army’s Surface Deployment and Distribution Command and the United States Transportation Command. With the end of naval manning of auxiliaries in 2010, all of them are operated by MSC mariners, with some hybrid crews. No longer do MSC tankers and supply ships shuttle up to U.S. Navy auxiliaries attached to battle groups, but mariner-crewed oilers and combat supply ships are both shuttle and station ships for the U.S. Navy. Yet these ships lack two critical assets from their grey hull counterparts.

First, they have no means of defense at all. MSC ships, except for small arms, are completely unarmed. Ships that are intended to provide the fuel, ammunition, and vital supplies to keep an entire carrier strike group or Marine amphibious assault task force at sea lack even point-defense weapons. In the world wars, the U.S. Navy assigned armed guard detachments to merchant vessels to defend the ships. While Kaiser-class oilers have the mounts for close-in weapons systems (CIWS), they lack the weapons. If an enemy nation wanted to eliminate the threat of the U.S. Navy, why would it go head-to-head with a Nimitz-class carrier when all it could to do is wait, shadow, and sink unarmed supply ships and then wait for the task force to run out of gas?

Additionally, those mariners who now find themselves not dead or killed in the initial attack, but afloat in a life raft, face another challenge – what is their status? Not whether they are dead or alive, but are they considered veterans? They face on a common day the same challenges and threats as that of U.S. Navy sailors, but they are not considered veterans. Even those mariners that experienced the Second World War had to wait over 40 years, until 1988, to get their service acknowledged as veteran through a lawsuit.

Some argue that merchant mariners are contractors and therefore do not deserve this. But how many contractors command assets in the Unified Command Structure of the military? No contractor commands a squadron in the Air Force, or a battalion in the Army or Marines, yet one-fifth of the Navy’s ships have a merchant mariner in command. The Navy gets all the benefits of a sailor without giving the mariner those same benefits. That is a deal, but for the Navy.

Some say the easiest solution is to replace mariners on the 60-plus ships with U.S. Navy sailors, but it has been tried before. This unique arrangement came into being at the founding of the Navy. The first ships brought into the Navy were merchant ships along the dock in Philadelphia. The two founding fathers of the Navy – John Paul Jones and John Barry – learned their trade as master mariners. In the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, private men of war (privateers) vastly outnumbered public men of war. In the Civil War, mariners kept the Union army supplied along the coasts and rivers. At the end of the Spanish-American War, with a global empire, the Navy needed to prioritize its personnel and decided to hire a civilian crew to man USS Alexander, a collier. By 1917, almost all the Navy fuel ships were civilian manned by elements of the Naval Auxiliary Service. With the outbreak of war, and concerns of foreign elements in some of the crews, and a massive increase in the size of the Navy personnel, the crews of the NAS were militarized, and later the commercial passenger ships in the Transport Force. The Navy resisted civilian crewing, and in 1942 President Roosevelt placed the building, crewing, and operating of the commercial merchant marine in the hands of one person – Emory S. Land.

After the successes of the Second World War, the use of civilian-crewed merchant ships was cemented with the creation of the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS). It was expanded in 1972 when the first underway replenishment oiler, Taluga, was transferred to civilian control. While some in the Navy may advocate for removing the civilian crews from the MSC ships today, the Navy already lacks the necessary personnel for its current assets, let alone an additional 60 ships, or the expertise in handling such assets.

Creating Paths to Command

This comes to the final point – how to address the issues raised by the heads of the unions based on the current situation facing the Military Sealift Command. The solution comes from the history of MSC’s forerunner, MSTS, and its counterpart across the seas, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) of Great Britain. Within MSC’s command structure are five Senior Executives – Legal Counsel, Director of Total Force Management, Director of Ship Management, Director of Maritime Operations, and Executive Director. They are all stellar and outstanding qualified people, and MSC is fortunate to have them. I know many of them and have worked with some of them in the past. They have impressive biographies and two of them graduated from merchant marine academies.

Yet nowhere in the chain of command for MSC is a Master or Chief Engineer from the fleet. They serve as Port Captains and Engineers and advise area commands, but there is no career path from the deckplate to the headquarters. That is a fundamental flaw in the organization and leads to the disconnect currently besetting the fleet.

In comparison, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary is commanded by Commodore Duncan Lamb. He has been in the RFA for 38 years and commanded many vessels in the fleet. His announced successor, Capt. David Eagles, has served with the RFA for more than 30 years. Unlike MSC, the RFA integrates their personnel into the command structure of the Royal Navy and therefore they have the opportunity for billets ashore and work within the shore base Navy.

What works for the Royal Navy may not work for the U.S. Navy, such as how Prince Edward* is the Commodore-in-Chief of the RFA, and they are much more regimented than MSC. However, they do have Royal Navy detachments on board for self-defense. The Royal Navy has a better understanding of how RFA ships work as demonstrated by their integration into the fleet during the Falklands Conflict of 1982.

A model where MSC mariners, starting at the junior level – 2nd Mate or Engineer – have the option for a career path that would involve assignment ashore to MSC area commands and fleets may better inform naval personnel of the particular needs of merchant mariners. Additionally, the appointment of senior master or chief engineer as vice commander at both the area command and headquarters level could ease the transition of new commanders who have little to no experience with MSC and provide a conduit and perspective from the fleet to the headquarters.

It is very doubtful that the Navy would allow any of its commands to be structured in a similar way. A small group of naval officers – 323 active Navy sailors – oversees MSC from its headquarters in Norfolk, to the five area commands and in dozens of offices around the world. This disconnect, with officers and civilians who have never served or commanded vessels with merchant marine crews or any of the types operated by MSC, explains why the issues raised by the union heads pervade the fleet. It appears that the role of merchant mariners in the role of national defense is reaching an inflection point.

Conclusion

Merchant mariners crew the fleet auxiliaries providing fuel, ammunition, and supplies to the U.S. Navy at sea. They operate the afloat prepositioning ships that would deploy the initial elements of Marine and Army brigades, along with materiel to a potential battlefield. They crew the 61 ships maintained by the Maritime Administration in the Ready Reserve Force and MSC’s sealift force, and they crew the 60 commercial ships of the Maritime Security Program. They are foundational to the nation’s ability to maintain, deploy, and sustain its armed forces abroad, and they cannot be easily replaced by naval personnel.

Yet despite this vital role, they lack representation within the command structure of the U.S. Navy. They are taken for granted by the Department of Defense and the public in general. They are overlooked in most strategic studies of American military policy and posture. And yet it is not clear whether in a future war the nation will be able to count on the U.S. merchant marine as it has in past conflicts.

This issue is not one caused by Admiral Wettlaufer, or any of the previous MSC commanders. It is a problem that has manifested itself as the command evolved from a primarily transport force of cargo, troops, and fuel, to one that is firmly integrated into the fleet structure in terms of ships. But the same cannot be said of its personnel.

MSC has undergone periodic transformations, alterations, and inflection points, and COVID-19 may be one of those moments. A group of former commanders, retired masters and chief engineers, and experts in the field should be formed to examine how to restructure MSC and present recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy and Chief of Naval Operations. The Royal Fleet Auxiliary and past civilian shipping entities can serve as models for how Military Sealift Command can proceed into its 72nd year of existence, and ease the issues facing the fleet and mariners today.

Salvatore R. Mercogliano is a former merchant mariner, having sailed and worked ashore for the Military Sealift Command. He is an associate professor of history at Campbell University and an adjunct professor at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. He has written on U.S. Merchant Marine history and policy, including his book, Fourth Arm of Defense: Sealift and Maritime Logistics in the Vietnam War, and won 2nd Place in the 2019 Chief of Naval Operations History Essay Contest with his submission, “Suppose There Was a War and the Merchant Marine Did Not Come?”

*Editor’s Note: Prince Andrew was originally listed as being the Commodore-in-Chief of the RFA when it is Prince Edward.

Featured Image: SEA OF JAPAN (Nov. 16, 2016) The forward-deployed Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Barry (DDG 52) conducts an underway-replenishment with the Military Sealift Command (MSC) Dry Cargo and Ammunition Ship USNS Richard E. Byrd (T-AKE 4). (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Kevin V. Cunningham/Released)

Hello there , an interesting article – I have worked for the RFA with nearly 34 years service and now a bosun’s mate – I have seen a lot of changes over that time -we have 4 new Tide class tankers with new equipment so always learning new techniques with these new ships – as for self defence we do take force protection seriously and generally we are well looked after in these troubled times . We do lots of continuation training regularly covered by FOST staff . ISM audits are carried out to make sure all safety procedures are complied with. Training new entrants in the various tasking that we do . Opportunities exist if you do want to move up the ladder and it can be a rewarding career if you can stick it out .We are all merchant seaman from the captain down to the lowest rating and embark

a Royal Navy flight if a helecoptor is onboard . Our tasking is varied be it solid and fuel support to other ships, disaster relief , C.N.support to U.S Coastguard , escorting merchant shipping in various trouble spots around the globe .

Nobody saw the Covid 19 crisis coming and we adapted accordingly with stringent safety routines to prevent it coming onboard my last ship – having just completed a successful 6 month trip regularly being updated by command I probably was safer on the ship during the lockdown , I know some seaman especially in the cruise ship sector have spent considerabley longer away from their families and this issue needs to be addressed by various government agencies so there is a level playing field for all employees.

A correction to your article Prince Edward is the Commodore in Chief to the RFA and not Prince Andrew .

Kind regards .

A few very minor corrections/additions to this article:

– There was a USN chaplain on board the USNS AMELIA EARHART for a couple of weeks after the incident with 3rd Mate Johnathan Morris.

– Many CIVMARs are now 100+ days overdue for relief. I know of several that are over 150+ days.

– CIVMARs do not have access to ‘real’ shipboard postal services, and the USPS website does not function with the onboard networks.

– The official policy of MSC is that no matter how long a CIVMAR is deployed (on ship), they are only granted the opportunity for 30 days of leave without having to beg their detailer (APMC, on shoreside, office workers, usually no maritime experience) for more time. Even if a CIVMAR has the leave, they cannot unilaterally choose to use it without involving their detailer. It is quite common for detailers to harrass or seek retribution against CIVMARs who have requested leave extensions. Please see MSFSCINST 12631.1 of 9 April 2009 and N12 Memorandum of 25 Jun 19 “End of Tour Leave Policy” signed by A.M. Kallgren. Certain detailers have quite loudly proclaimed that people will not be granted leave extensions regardless of how much leave the CIVMAR has or how long the CIVMAR has been deployed.

– Overdue pay can be denied if a CIVMAR takes ten or more consecutive days of leave AT ANY TIME during their deployment (COMSCINST 12451.1 of 3 Mar 2020, section 4a.)

– There does not appear to be any communication between the detailers, the recruiters, or the admiral at any level that describes exactly how bad the manning issues are. I would highly suggest Admiral Wettlauffer or an aide acquire every single community report from 2016 to present and look specifically at the “N12 Weekly Snapshot” pages. Generate some historical charts based on the numbers found in the “Delta” columns. There is something more than rotten in Denmark involved.

The USMS (United States Maritime Service) should be brought back into being (it currently only exists at the academies) with ranks, ratings and benefits negotiated but at least equal to the USN. The USMS should take over the duties of the MSC. Further, all U.S. mariners should be members of the USMS. I understand that both current unions and the DoD would oppose such a suggestion but a negotiated USMS might be a good middle-ground resolution.

Great Job. AGAIN. You are on fire. Keep it up. You are providing a much needed perspective. Very Professional.

Were under paid , over worked , No time at home with family. When we are at sea the internet is slow. The supervisors meaning captains and chief Engineers or chief mate and 1st Engineers are belligerent to there workers .EEO Complaints are up and people are quitting at a high rate. The Navy need to come to the table to me the work place safer and the ships Communication systems better ? Like wifi on all the ships . And Raise the overdue money from $25 A day to $50 a day and if you overdue over 45 to goes to $75 a day .

Feb 19 was my relief date they had plenty of time to get me off Aug 21 I got releaved 184 days overdue I got paid 1.82 an hour …. that is a 24 hour calculation I’ve been with MSC 21 years great job the shore side is a different story all we are is a inconvenience to them for God sakes they don’t even answer the phone who are these people I’m sad

Why is Busby quiet in all of this? He needs to get involved.

Confining CIVMARS to the ship while Federal employees come and go at will is ridiculous.

Capt. James R. Shinners, KP ’62D

Please help the Mariners that were exposed to Agent Orange in the Vietnam War

I declined a good SeaLift position + bonus a few weeks ago when was told by MSC staff member that even during 5-6 week NEO class all new hired CIVMARs are not allowed to travel during weekend outside Virginia. I live out of state and don’t get why I cannot see my family or even take care of my apartment. Not to mention that being locked on a ship in Norfolk or other homeport without a chance to go to the post office etc is just ridiculous.

It’s time MSC joins the rest of the merchant fleet! No more long deployment with no time home. There’s absolutely no reason there can’t be a standard rotation of 60 days on, 60 days off. Ships over seas could do 80-80 or 90-90 while smaller vessels that stay in the states could do 45-45 or even 30-30. Their new salvage vessels can’t be crewed fully with knowledgeable sailors because we don’t want to work a crazy schedule that will stress our home life.

MSC has deteriorated so much since this article. Average overdue time is 90 days. The base is trying for 4 months on 2 months off rotation but that is still a long time away from home. Its amazing that people with connections do not have a hard time getting a relief. The lady who runs the CSU East has a son with MSC who seems to get amazing assignments and reliefs on time. Might be time for IG to take a look behind the curtain at MSC Headquarters.

I tried working afloat for the MSC after crewing on a pre-positioning ship which was a chartered commercial ship during the Gulf War and was also a submarine veteran. It was obvious that MSC was run by naval officers who thought that it was acceptable to demand 11 months at sea per year of CIVMARs when we got 2 months off after a 4 month tour on the commercial vessels. Then also there was the issue of the civilian conversion not having been done forcing us to live in mass open bay berthing. I put up with that for a couple of weeks before quitting and returning to commercial ships. Why put up with such nonsense when you could easily get a regular merchant ship just by calling 1-800-SEA-CREW? But the regular merchant marine seemed poorly run as well so instead of paying to go to cram school to get a 3rd officer’s ticket I instead went to barber college believe it or not, in spite of the fact that I had a teaching credential and 7 years teaching experience. Barbering worked out for 20 years because I was self employed at least by renting a chair in a going shop. The nonsense involved in teaching school was simply unbearable and the teaching profession is in a state of collapse today as anyone could’ve predicted even 40 years ago.