Sterling, Brent L. Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts. Washington DC, Georgetown University Press, 2021. 336 pp. $39.95 (soft cover). ISBN: 1647120594.

By LtCol Adam Yang, USMC

The conflict between Ukraine and Russia has already raged on for nearly two years and continues to provide the US Department of Defense an incredible opportunity to derive insights on the changing character of war. Similarly, Israel’s offensive against Hamas terrorists in Gaza today may likely reveal new insights on urban and tunnel warfare in densely populated areas.

Though it can be quite hazardous to draw definitive lessons for an ongoing conflict, there is a remarkable appetite across the defense community to extract preliminary lessons and implications from their unique vantages. For observer nations, the spectacle of a foreign conflict might reveal critical battlefield information on new capabilities and concepts and provide the critical information-edge needed to overcome an opponent in future battle. Why learn the hard way when you can learn from the wartime successes and challenges of others?

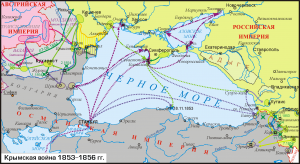

Though there is plenty of literature on learning and training processes, Brent L. Sterling’s book, Other People’s Wars, provides a structured academic view into the lesser-examined topic on how, specifically, the US military has served as third-party but direct observers to learn from foreign conflicts in the field. Sterling delves into four historical examples when the United States deployed some of its best military minds to learn up close battlefield lessons in a bygone era that lacked the information systems we enjoy today. The four cases are the Crimean War (1854-56), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), and the Yom Kippur War (October 1973).

In each case, Sterling provides a snapshot of each respective conflict and answers four basic questions: 1) How did the US military attempt to identify lessons, 2) What lessons did the services identify, 3) How did the services apply those lessons, and 4) What were some of the implications of those applied lessons? As an overarching theme, Other People’s Wars is less about the specific lessons derived from each conflict and more about the leadership, bureaucratic, parochial, and cultural challenges military organizations face when they attempt to “learn” lessons and enact resource decisions based on foreign battlefield information.1

The academic foundation of Other People’s Wars blends literature from military innovation, information diffusion, and organizational learning and Sterling, thankfully, keeps much of his analysis away from academic jargon. Sterling rightly distinguishes the act of “drawing a lesson” and “learning a lesson.” The former implies the process of collecting, observing and deriving a valid insight from a foreign conflict. The latter idea of learning itself relates to how organizations actually apply observed lessons to improve their combat effectiveness.2 In other words, Sterling suggests that organizational learning does not truly occur unless there is actually change in organizational behavior based on related combat findings.

Across four cases, Other People’s Wars offers the gritty details how the US Army, Navy, and Air Force leaders strived to glean insights from foreign conflicts based on their unique political climates, budgetary constraints, and cultural lenses. The cases then show how military organizations enacted or failed to enact change after returning home with their troves of newly acquired tactical knowledge. The decision and authority to initiate such studies were almost exclusively top-down given the political sensitivities of their work and invasiveness with scrutinizing foreign armies in active combat zones. The ideal method to learn from foreign conflicts is to embed neutral observers with all belligerents to capture reciprocal perspectives of their engagements. However, at least in the Sterling’s cases, this standard was rarely met save for a few limited instances.

For example, during the Crimean War in June of 1855, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis dispatched three trusted Army officers to Crimea via Russia. However, though acting as neutral observers, these officers were blocked by both sides (France and Britain on one side and Russia on the other) and lost valuable observation time waiting in neutral areas because local commanders did not want any distractions amidst active battle. Later, during the Russo-Japanese War, the US War Department’s General Staff dispatched eight observers to observe both Japanese and Russian forces with greater success. Those observers gained enough access to observe the aftermath of the Japanese siege of Port Arthur in December 1904, and directly monitor the Battle of Mukden on the front lines in February 1905 – two of the most decisive battles of the entire conflict.

When the United States could not gain direct access to a foreign battle, it leveraged third-party observers for direct reporting of critical capabilities and systems. Sterling shows how the US military frequently leaned on its network of defense attaches. During the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, US defense attaches in Spain, Germany, Italy, and Russia, developed a dense network of local contacts and foreign officials to help collect.3

The Pitfalls and Perils of Learning from Others

For US military personnel attempting to learn from foreign conflicts, Sterling draws a clear line between their observations, drawn lessons, and reports back to senior military and political leaders. However, it is the process of stateside reception and critique and of those lessons that complicates the learning process in each historical case. In some instances, the US Army or Navy enthusiastically adopted lessons from the front lines that would trigger systematic doctrinal and capability changes across their Services.

To illustrate this point, Sterling describes how the Army dispatched Major General Donn A. Starry – a future Commanding General for the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (1977-81) – to capture lessons from the Israelis shortly after the Yom Kippur War in 1973. In turn, the Army would transform Starry’s findings, particularly those related to combined arms and the need for greater air-ground coordination, to guide the development of its famed Air-Land Battle doctrine over the next ten years. Yet, this example tends to the be exception rather than the norm in terms of bureaucratic change. Sterling identifies at least five recurring challenges the US military faced when learning from others:

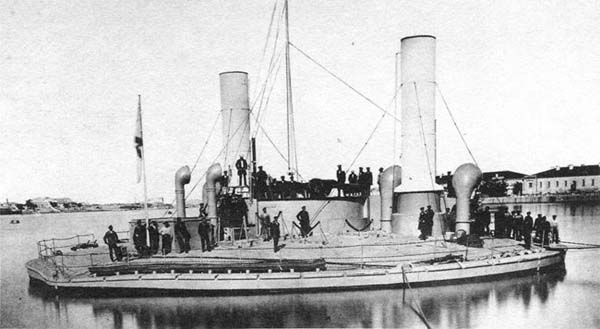

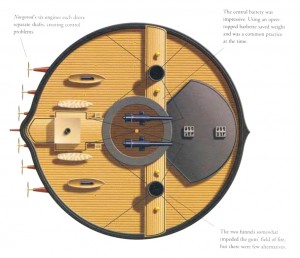

Preexisting Preferences. A recurring culprit in this book, prior organizational preferences shape every aspect of a learning process, including what data to pursue, how to interpret such data, and whether any “lessons” are relevant to the service. The Navy believed that the Russo-Japanese War validated Alfred Thayer Mahan’s core idea that “concentrating capital warships was the key to winning fleet engagements” and that defense-oriented alternatives were a losing proposition for any great navy.4 Though this lesson may be have been “correct,” the Japanese never allowed US Navy personnel directly near the waters of Port Arthur and forced the Navy personnel to interpret battle information from Japanese liaisons and foreign attaches that had first-hand accounts of the battle.5

Failure to Identify What Happened. The inability to access relevant battlefield information undermines the entire learning process. Surprisingly, the act of sending multiple observers to document different battlefield phases and stages tended to generate contradictory and conflicting reports, which buried important lessons under the noise and weight of lesser observations.

Application of Disputed Lessons. Senior leaders with bureaucratic power can build “artificial consensus” and use ambiguous lessons to muscle through preferred programs. Sterling cites how Secretary Davis and some Army leaders used the Crimean War to justify the development of more masonry fortifications after claiming this is what allowed Russia to repel the assaults by the Allies, rather than focusing on the failure of Allied coordination during the assault.

Rejection or Ignoring of Lessons. This pitfall occurs when military forces ignore or write off important observations because they do not directly apply to their current activities. Sterling shows that in the 1930s the Army Air Corps failed to take notice of German close air support tactics because they were primarily focused on the effects of strategic bombing.

Identifying Contradictory Guidance. Another common challenge includes the identification of two or more relevant lessons that signal contradictory behaviors and investments. After the Yom Kippur War, the Army observers separately noted that it was more beneficial to boost the “tooth” (i.e. combat power) versus “tail” (sustainment) ratio – and vice versa – to generate the greatest utility from its armor formations. Consequently, the Army diluted its limited resources for several years as it experimented with both courses of action.

A Modern Context

As the conflict in Ukraine nears the end of its second year, the Department of Defense and other foreign militaries will continue to capture what they believe to be relevant information on the conflict inform resource decisions. Modern information technologies provide military experts and researchers incredible access to information and individuals at incredible rates, however, an on-the-ground investigatory approach even today would yield incredible insight and knowledge that one does not get from distant observation. Even Carl von Clausewitz recommended that military leaders “should be sent to observe operations and learn what war is like.”6

Sterling’s book offers a historical gateway into this phenomenon and provides remarkable insight into the benefits and challenges of learning from foreign conflicts from an American point of view. Other People’s Wars mostly focuses on the challenges with institutional learning and, admittedly, does not attempt to detail how to overcome such issues. Sterling writes that there are “no easy remedies;” but stresses the need for organizations to build complete and objective histories of events, and to disseminate findings widely to solicit a broad assessment of findings. For a different view on this subject, readers can also explore John Nagl’s dissertation turned book, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, as he elucidates how organizational culture skews organizational learning by comparing the US Army and British Army experience with counterinsurgency.

Overall, Brent Sterling does a remarkable job illuminating the benefits and challenges of organizational learning in the US military. Though this subject has been written on in other forms, Other People’s Wars captures the US military’s historical experience methodically and with great clarity, purpose, and evidence. While these cases are historical, the stories related to leadership, hubris, and bureaucratic slow-walking are timeless and seemingly reminiscent to the strategic churn that occurs today. This book is a must-read for military professionals, educators, and those interested in organizational change.

Lieutenant Colonel Adam Yang, PhD is a Marine Corps strategist assigned to the Strategy Branch in the Plans, Policies, and Operations directorate of Headquarters Marine Corps.

References

1. Brent L. Sterling, Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2021).

2. Sterling, 6.

3. Sterling, 138–39.

4. Sterling, 74.

5. Sterling, 62.

6. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton University Press, 1989), 122.

Featured Image: Ukrainian troops participate in a military exercise. The main task of this brigade is to shoot down Shahed-136/131 drones used by Russia to attack Ukraine. (Photo via the “Rubizh” Rapid Response Brigade of the National Guard of Ukraine)