Introduction

Maritime security is at its heart an exercise of risk reduction, action deterrence and event response – no nation ever has enough resources allocated to enable its forces to be everywhere they need to be all the time. So in reality defence and security has become a bit of a mirage; aiming to look more substantial and solid that it actually is. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the circumstance of maritime security, and the protection of a nations Exclusive Economic Zones, or EEZ. An EEZ is the area of sea/sea bed that a nation administers, for want of a better phrase ‘owns’, and therefore can control/monetize the extraction of resources (such as Fish, Gas, Gold or Manganese) from, and which are becoming increasingly important to national economies – in fact their societies as a whole. However, a nation cannot control or monetize anything if it doesn’t actually have control of it, and just as a city cannot be policed from the secured, nor a battlefield secured just from air[i], neither can an EEZ. Due to this, a specific type of vessel has not so much appeared (as navies have always fulfilled the role with other vessels) as evolved as the areas required to be patrolled have expanded. Although instead of reviving one of the old names, Brig, Sloop or Swan, as was done with ‘Frigate’ in WWII, a name based upon the role the vessel carries out has been generated; OPV.

OPV is of course an acronym, and stands for Offshore Patrol Vessels a name which whilst being apt is also a little bit of a let-down; especially as with the expansion of EEZs across the world these vessels might be better termed Ocean Patrol Vessels, or perhaps even EEZPVs. That however is long past the point of debate, what is not though is the role that these vessels fulfil for the nations which operate them. Whether they are naval patrol ships or coast guard cutters, OPVs can be usually be defined as vessels which displace less than 3,000tons, are capable of operating in open ocean, and which are the maritime presence equivalent of the ‘police foot-patrol’ (or ‘bobby on the beat’), fulfilling a similar position in terms of maritime security. They are not therefore, nor can they ever be, ‘frigate replacements’[ii], but they are vessels which have a different mission spectrum that brings its own requirements in terms of armament, equipment and sensors.

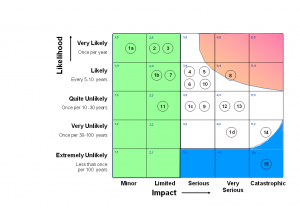

These factors are of course dictated primarily by their projected mission profile. However, whether or not the nations possess vessels other than the OPVs, for example as in the case of Australia, Britain, France and Japan with frigates and destroyers; their OPVs do not need to be as well armed as nations for which OPVs constitute the primary surface vessel type. Furthermore, there can also be factors of internal or inter-governmental politics which can have an impact as to how a ship is designed – for example depending upon whether the vessels are domestically constructed, equivalent of the foreign ministry might well have influence as to where they are constructed. Beyond these factors are can also be things like tradition (possibly better termed habit). These are all things which factor into a design, many are not entirely relevant to the question as they have no direct bearing on what OPVs do. There is though, an impact on design which must be discussed, for both its negative, as well as positive impacts – and that is the matrix planning system.

Key: Key:

|

| Figure 1 – The Framework for an objective comprehensive Strategic Defence Review, published by UKNDA February 2010 – Senior Author R.Adm Jeremy Larken DSO[iii] |

Everything looks so neat and ordered in matrix, the world is nicely divided up and in many ways it as excellent representation of what is needed for what missions – unfortunately there is a problem with it. The world itself is not so neatly divided up. There is no way of factoring what a government wants to be able to do in comparison to how much it is willing to pay. It can in many ways also become a substitute for proper operational planning and analysis, as individuals fall back on “well this is what the matrix projects is likely to happen” logic. Why is this a specific problem for OPVs? This is because the majority of what they do either doesn’t have a place on the matrix, or fits in the Minor or Limited categories.

There is also the point that while something may be unlikely, that if someone had asked the question in 1913 ‘will there be a World War starting next year which will last five years, cost millions of lives and see the emergence to practicality of whole evolutions of equipment?’ – the answer most likely would have been a no. However, while an event might only be predicted to happen just once in a hundred years, will it happen in year 19 or year 99 of that 100 year span? What was the likelihood that the next World War would take place a little over two decades after the first? This creates a problem, because if something isn’t going to happen for a long time according to odds, it becomes very tempting to cost conscious governments with bills to pay to think they can put it off till they need it. The reality is though with procurement cycles taking twenty plus years before equipment enters service this can have a big impact, as something as complex as a warship cannot be procured overnight. This is an impact most visible when considering vessels at the opposite end of the spectrum of naval warships.

In 1967 when the British government made a decision not to procure aircraft carriers[iv], they certainly didn’t believe that less than fifteen years later they would be fighting a war which was entirely dependent upon naval aviation[v]. In 2010, when the British government again decided that an aircraft carrier capability gap was necessary (without taking the precaution of arranging cover); who would have predicted the Arab Spring, Syria, the rise of the Islamic State, the Ebola Crisis, and Russia acting up? These and all sorts of other minor crises where organic carrier air power wouldn’t have necessarily been the first response, but would have been very useful as a bedrock capability from which to conduct/lead/support operations and project influence.

In the case of OPVs, it’s more complicated to show, as so much of what vessels of this type do is only really shown when they’re not there to do it. It’s like the security guard or the police officer walking the beat[vi]; what value can be placed on the crimes which are not committed because the would-be perpetrators decide to go elsewhere for less risky pickings? These though are concepts which are readily understood, the concept and role of an OPV is less understood, because unlike the police officer walking his patrol, or the security guard at the entrance, people see them every day – they are the familiar shapes, a recurring presence, that makes many feel safer. Unfortunately for OPVs much of their work is not only beyond visual range, it is so far over the horizon that many lack any comprehension of what they do; a situation compounded by the fact that much of what they do is definitely not eye-catching or dramatic enough for modern revenue driven news media to pick up and put on television, the news-stands or online.

Primary Mission – Protecting & Patrolling the EEZ

When discussing the bounty of the sea, the first thing which will occur to most people is fish, and fishery protection, i.e. the enforcement of quotas, rights, and ground. Now these can all become complicated when looked at in detail, but in reality it comes down to the question of ‘who fished what, where?’. This is therefore a mission which requires an OPV to maintain very good situational awareness of its patrol area, and the ocean beyond that. To do so it will probably need to be able to receive and process large volumes of data from external sources, i.e. international systems like the European Maritime Surveillance Network[vii]. Finally of course when they do find vessels which are contravening the rules, or look suspicious they need to be able to deploy and support ship search teams in order to examine that vessel more forensically than is possible by radar. Fishery protection has developed a harder edge in recent years, probably starting with the second and third ‘Cod Wars’ between the United Kingdom and Iceland[viii] ; but progressing significantly now with events in the South[ix] and East China Seas[x] where fishing vessels and their protection of fishery rights has become almost a proxy for territorial (or EEZ) expansion at the expense of neighbours territorial rights[xi]. That this might induce repercussions and copycat actions in other parts of the world, is something that nations can only discount at their own peril.

Design Requirements of Fishery Protection:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

Fish though are not the only bounty of the sea, oil, gas, as well as many other minerals and ores are all to be located and extracted from it[xiii]. With the modern understanding of the environmental impact of such activities, and combined with their sometimes great distances from land mean that for governments the mission of oversight is both very important and very complex. OPVs and other naval vessels will often be a principle methodology of government in keeping over watch over these activities. There has also been in recent years, growing examples of nations using Rigs, as well as fishing fleets, to try to expand or strengthen their claims to watery territory. This has been most recently seen in the South China Sea[xiv], but have also been a feature in disputes between the United Kingdom and Argentina in the former’s EEZ around its Falkland Island Territory[xv], as well as Africa. The fact is once rigs are in place they are very difficult to remove without damaging that which a nation would wish to preserve or causing an all-out conflict; therefore the best method of dealing with these threats is by prevention – which requires presence. Put another way, if possession is nine-tenths of the law[xvi], and it is possessing the sea that a nation can draw sustenance from the sea, the presence is how a nation shows and maintains that possession.

| Figure 2. USCGC Waesche (WMSL 751), the second of the US Coast Guard’s National Security Cutters to enter service, shown in this picture with KRI Sultan Iskandar Muda (SIM 367) and KRI Banda Aceh (BAC 593) a corvette and landing platform dock of the Indonesian Navy[xvii]. |

Design Requirements of Resource Protection:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

Trade protection is a mission set which is both larger than Fishery Protection and Resource Protection, but at the same time more narrow. In the ‘peacetime’ context of navies, it is a counter piracy, counter-interdiction/interdiction, Freedom of the Seas and navigation which for the pillar groupings of this mission set[xviii]. Furthermore, unlike the previous two mission sets there are just as definite advantages to using larger ships than OPVs for some operations, as there are definite advantages to using OPVs for them[xix]. Before examining the capabilities required though it is probably best to define three of the missions, as whilst piracy and its resulting counter-piracy missions regularly make the press, counter-interdiction and Freedom of the Seas missions are not so frequent. Interdiction and Freedom of the Seas could be confused as the same mission, as both involve disruptions through trade – however, whilst Interdiction refers to undue checks being imposed or a targeted mission by a nation on a specific merchant vessel (i.e. if the Argentinians had tried to stop the oil survey ship conducting its mission in the Falklands EEZ that would have been an Interdiction) whereas Freedom of the Seas refers to a more ‘blanket’ denial of movement. Due to these differences though the level of justifiable response (or proportional response[xx]) and international response can be very different (as after all a Freedom of the Seas situation would most like generate a multi-national task force response) and therefore require different things from the nation, so obviously require different things from its ships.

The advantages of larger ships is of course greater endurance, more firepower, more personnel/space to do things with and most importantly they are a bigger statement of interest – something which can be especially important when the mission is Freedom of the Seas orientated. On the other hand though smaller ships can establish precedent, and the self-defence armament of an OPV could be viewed as ‘less provocative’ – although at the same time this means they could be less able to protect themselves if something goes wrong. In the end for such operations it might well be in the future, depending upon the threat level judged sensible to have the OPV do the actual Freedom of the Seas demonstration or Counter-Interdiction while a larger vessel (probably a destroyer as that would be most suitable due to its area air defence capability) stands off to provide support. This though is not the only role for which there are advantages on both sides.

Counter-interdiction is arguably the most complicated mission, and one which has been a far more frequent occurrence than Freedom of the Seas. Interception of specific vessels or a specific nation’s vessels by another nation can be an attractive policy; for example the activities of Argentina with British survey vessels (which are announced but not carried out)[xxi], China with American intelligence ships[xxii] or Israel with Gaza[xxiii]. In the case of each of these nations, the policy has been weighed up and found to be advantageous – the problem though for other nations is how to prevent interdiction. This can be a very sensitive mission, in the case of Britain it is arguable that it was the presence of naval ships in the region, the OPV HMS Clyde[xxiv] and the ‘Atlantic Patrol Tasking South’[xxv] – a frigate or destroyer and an auxiliary, that discouraged the Argentinian Government from active interdiction rather than using diplomatic efforts to passively impact operations by getting other nations to deny access to ports[xxvi]. This is a form of interdiction which is of course not able to be solved by modern definitions of ‘gunboat diplomacy’[xxvii] due to modern perceptions on the action of nations; but the Argentinians stopped at these more passive measures. Just as counter-interdiction is a role for OPVs, so is interdiction itself; primarily from the perspective of counter smuggling operations – the smaller size of an OPV in relation to other naval ships allowing it to get closer to shore to support its boats if a smuggling vessel tries to make a dash for it through shallow water. These though are principally (or worst case scenario in terms of interdiction) state-on-state issues, the other two pillars, navigation and counter-piracy, are of course non-state in origin.

| Figure 3. HMS Clyde on patrol in the South Atlantic[xxviii], often her and her crew are the only British presence for hundreds, if not thousands of miles; this is not an unusual situation for an OPV to find itself in and therefore has to be a principle consideration in their design. |

Navigation, could seem a strange addition in the age of satellites capable of providing accurate measurements of a ships position down to the nearest meter anywhere on the globe. Unfortunately, not all ships have that technology; although such a state is becoming increasingly rare. Still though navigation is important, especially in making sure ships stay in their ‘correct lane’. This might seem strange but in the oceanic choke points like the English Channel, Straits of Gibraltar, Strait of Malacca and Strait of Hormuz, there are so many ships that that the effect of leaving their lane would be much the same as a car driving the wrong way on a busy road – mayhem. Whether it is down to inaccurate navigation equipment, engine malfunction, steering difficulties or human factors, much the same as with cars on the road, the authorities have to resolve the issue. This mission is exacting on a ship, it requires it to be powerful and strong so it can act as a tug if necessary, it needs to be able to operate in all weathers and sea states and its needs to be reliable so will need to have perhaps even more redundancy built into it that normal ships. Despite the disasters which have happened when governments haven’t been adequately equipped for navigation events, it is the non-state trade protection role of counter-piracy the garners most attention.

Whether on the East or West Coasts of Africa, the Singapore Straits (or further up into the Straits of Malacca) or in the Caribbean[xxix] piracy impacts on not just the way ships are operated, but costs of shipping insurance is increased, some shipping lines are turning to armed guards others using naval architecture – and all these costs will inevitably be passed on to consumers. The role of OPVs in this is course obvious, they are not about tackling the causes of piracy (whether that is economic weakness, greed or politics), but about providing a cost effective presence to deter potential pirates by raising the potential cost for them. The fact that so far it is usually a frigate or destroyer that nations have deployed, is not only testimony to the almost explosive capability boost that can be offered to OPVs by UAVs (and the benefits of organic air power enjoyed by most modern escort vessels), but also to dearth of vessels available to (especially western) navies after the post-Cold War ‘peace dividend’[xxx]. Furthermore, OPVs are due to their more limited equipment, considerably less expensive to acquire, so for those nations which wish to not rely upon other nations to provide counter-piracy cover in their waters, they represent a more viable option than even perhaps a more war orientated small vessel such as a corvette.

Design Requirements of Trade Protection:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

Border patrol, just as with land borders and air space, a nation has to patrol its maritime borders; such an action is enshrined in Fishery and Resource protection roles, but in reality is its own set of missions.

When a nation challenges another by entering its national waters[xxxi], there are of course various responses available to most nations – but the most effective is of course an ‘equivalent’ or ‘proportional’ response. Put another way, whilst aircraft can overfly a ship, they have to return to base, whereas a ship can shadow, can if necessary send a party across to enquire in person as to what is happening; in simple terms a ship is a far stronger response to a ship, even if smaller, as long as it’s able to keep up and stay on station, protect itself if some suddenly changes and fly’s the flag high that will all count for a lot. This is not just something small nations have to contend with, for example in 2014 Britain dealt with two separate incidents, one involved HMS Severn (one of Britain’s River class OPVs) having to escort Russian Landing Craft through the English Channel[xxxii]. However, when the Russian aircraft carrier, Admiral Kuznetzov[xxxiii], and its task group enacted a similar performance Britain of course required a ‘bigger presence’ therefore HMS Dragon (a Type 45 Destroyer[xxxiv]), the Fleet Ready Escort[xxxv], was called upon[xxxvi].

Figure 4. Chinese built Nigeria OPV, based on the Type 056 Corvette design[xxxvii] Figure 4. Chinese built Nigeria OPV, based on the Type 056 Corvette design[xxxvii] |

|

Figure 5. Chinese Type 056 Corvettes[xxxviii], the Chinese answer to the problems of maritime border patrol, well-armed, produced in large numbers and soon to feature ASW versions[xxxix]. Figure 5. Chinese Type 056 Corvettes[xxxviii], the Chinese answer to the problems of maritime border patrol, well-armed, produced in large numbers and soon to feature ASW versions[xxxix]. |

|

Design Requirements of Border Patrol:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

|

Figure 6. HMS Severn alongside HMS Belfast on the Thames (Author’s Own Collection) – Britain’s tools of Presence Past and Present. Figure 6. HMS Severn alongside HMS Belfast on the Thames (Author’s Own Collection) – Britain’s tools of Presence Past and Present. |

|

Another diplomatic role that OPV’s have to undertake is that of ‘presence’, showing the flag, port visits, etc. Presence is about demonstrating a visible and most importantly ongoing commitment to a region, with the aim of promoting stability and protecting national interests. This is a mission which all naval ships are required to carry out, because by the nature of the presence mission, quantity becomes a quality of its own[xl]. This is because each visit represent an opportunity to build relationships. The more that can be done to build, and strengthen, relationships, the greater the foundation that will be constructed for the exercising of diplomatic power (sometimes referred to as informal or even soft power). This matters because in the world of shrinking defence budgets, relationships with the potential that they represent for co-operation, information and alternative options, could well be crucial either by having better intelligence to enabling heading off of potential troubles before they become trouble, or being able to respond more efficiently/prepare forces when trouble happens.

Design Requirements of Presence:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

Counter-terrorism is its own area because it is a growing problem, despite their similarity to, and often overlap with, counter-piracy missions. This is due to the fat that whereas counter-piracy missions have a degree of predictability about them (enabling scalable resources to be deployed in the vicinity), terrorist missions are not as predictable; most importantly the difference is in motive. Piracy is about financial gain, if it happened on the high street it would be called robbery; terrorists might seek financial gain to support operations, but they are not motivated by it. Furthermore, whilst traditionally the deployment of marines or naval infantry with machine guns have been sufficient augmentation of firepower to deal with any eventuality this will not always be possible[xli]. Another difference is in comparison to pirates, as time has gone on terrorist organisations have been growing in terms of equipment, firepower and training; currently this has mostly been felt in terms of land conflict[xlii]. However, it can only be a matter time before these organisations or similar take to the sea[xliii].

The reason this is so, is because of the value of targets available in comparison to the relative lack of security, and the likely response times of government forces must make them attractive. Should these forces take even basic anti-tank missiles, or surface to air missiles, to sea with them, then many nations could find the lightly armed OPVs they have in service literally overwhelmed. Even at current levels, in order to have enough firepower aboard them, then under most circumstances either the nation will have needed to be forewarned, or it will be scrambling to react to events – and the ships themselves will not have enough of the ‘right’ personnel (i.e. marines or equivalent) to effectively deal with the situation.

Design Requirements of Counter Terrorism:

Bold = not previously mentioned |

| Figure 7. P840 HNLMS Holland, lead ship of the latest class of Dutch OPV’s, at 3,750 tons, they are bigger than some navies frigates: but with a crew of 50 and space for 40 more, a hangar that can accommodate a medium helicopter, a 76mm Oto Melara Super Rapid main gun, a 30mm Oto Melara Marlin mounted in its ‘B’ position, supplemented by two 12.7mm Oto Melara Hitrole and six 7.62mm machine guns (the only manually operated weapons), when this is combined with an impressive sensor suite and a range of 5000nm at 15kts they represent a significant capability[xlv]. |

To be continued in Part II

Dr. Alexander Clarke is our friend from the Phoenix Think Tank in the United Kingdom and host of the East-Atlantic edition of Sea Control.

[i] (Masi 2014, Agencies 2014)

[ii] The nation most likely to face such a notion would be the UK, and really it shouldn’t as its current escort strength of nineteen frigates and destroyers is already well below that which is required by its patrol and task group commitments; it’s also a very strange situation to be in, as for example when the US Coastguard buys cutters, the USN navy doesn’t get told to buy less escort vessels, so why does the Treasury in the UK. Although this is not a recent phenomenon, John Ferris in his 1989 book Men, Money and Diplomacy; the evolution of British strategic foreign policy, 1919-1926 (published by Cornell) highlights the sometimes circtacious and often illogical in terms of naval or military strategy interventions by those seeking to secure the public purse – interventions which nearly always end up costing vastling more in the long run; something which has been well illustrated by story of the Queen Elizabeth II class (naval-technology.com 2014, Tovey 2014). As said above and a point which will be reiterated; OPVs and Frigates are very different ships, one is a relatively cheap maritime patrol asset, the other a high value anti-submarine asset that is capable of providing task group point air defence, naval gunfire support and viable anti-ship platform.

[iii] (Larken, et al. 2010, 17)

[iv] (Friedman 1988, 327-44)

[v] (Clapp and Southby-Tailyour 1997, Woodward and Robisnon 2003)

[vi] In this scenario, Maritime Patrol Aircraft are a sort of mobile CCTV equivalent, in the right conditions can provide identification, and are a sort of deterrent; but short of warfighting scenarios where they can actively engage targets they have limited capabilities to carry out the sort of missions discussed by this piece, e.g. unless they are seaplanes they can’t launch and recover boarding teams.

[vii] (European Defence Agency 2014)

[viii] (The National Archives 2014), recommend look up the history of the Turbot Wars

[ix] (BBC 2014)

[x] (Smith 2012)

[xi] (Dingli, et al. 2013, Hosford and Ratner 2013); interestingly the 1985 Plenary meeting of the Chinese leadership focused on hegemonism and expansionism as being primary causes of limited war – something they felt more likely to occur than full scale nuclear conflict (Tien 1992, 277). This can be read as especially interesting, considering recent the Chinese naval boom (reference), because as has been discussed since Julian Corbett wrote his Some Principles of Maritime Strategy 1911, the only truly limited war is that which takes place between two island powers or those separated by the sea (J. S. Corbett 1911, 48).

[xii] Rotary Wing UAVs are most likely (with current technology) probably the best choice, as whilst small fixed wing/net recovery UAVs like Scan Eagle (Insitu 2013, Defense Industry Daily 2014, Boeing 2014) offer much in terms of surveillance, the idea of ‘crashing’ any aircraft with live weaponry into anything when it can be justifiably avoided is illogical. The result could well be that OPVs end up carrying a mixture of such unmanned aircraft, maybe even more than their larger brethren as their role (which often include being on their own far away from support) depends upon maximising both the image and impact of their presence.

[xiii] The value of the sea’s resources have been known and understood for a long time, to such an extent that Sergey Gorshkov, Admiral of the Soviet Union used as a central platform for his arguments for the Soviet Union to build a stronger navy (The Sea Power of the State 1980, 6-27)

[xiv] (TheGuardian 2014, Tiezzi 2014, Heydarian 2014)

[xv] (Russian Times 2013, Drury 2010, Halliday 2014, MacErlean 2014)

[xvi] (Horrell 1991)

[xvii] (United States Government Work 2012): Whilst the National Security Cutters are included in this study, as they are OPVs in role and armament; in reality with a displacement of 4500tons they exceed some navies’ frigates in size.

[xviii] In ‘wartime’ it becomes arguably one of the most muddied and brutal parts of the conflict, and also is one of those areas where not a lot can be one, but everything can be lost (Bacon and McMurtrie 1940, 140-56). It is also an area of naval work is often difficult to ‘sell’ to political classes and the wider public, especially in times of financial hardship (in the 1920s & 1930s this brought out significant political skill and bargaining in the Admirals of the day (Babij 2009, 172)) – as Trade protection is possibly the least ‘insurance’ looking defence spending of any part of the defence budget, it is entirely deterrence and response. As such, when it works well no on notices it, and when it goes wrong the losses cannot be easily remade. The fact which makes getting it right, or at least the forces available as capable as possible, so important.

[xix] In a different time, there was a very wide ranging debate over the merits of cruisers, because within the limits of treaties they could either be made good for battle or good for trade protection, one requiring speed and firepower, the other requiring endurance and seaworthiness (Field 2004, 30-8). It is rather similar with the modern debates of Frigates and OPVs (especially the larger vessels of this type, like the French… and the USCG National Security Cutter); neither is actually really suitable for the others role, and it is an artificial argument when they are set up against each other.

[xx] (Anzalone 2010, Beehner 2006, Keiler 2009)

[xxi] (Russian Times 2013, Drury 2010, Halliday 2014, MacErlean 2014)

[xxii] (Shanker 2009, BBC 2009, Tyson 2009); but they Chinese have also despatched their own vessels to monitor multi-national exercises, even ones they are participating in (BBC 2014, LaGrone, China Sends Uninvited Spy Ship to RIMPAC 2014)

[xxiii] (Palmer, et al. 2011, Spelman 2013)

[xxiv] (Royal Navy 2014)

[xxv] (Royal Navy 2014)

[xxvi] (Gardner 2011)

[xxvii] (Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force 1981)

[xxviii] (Royal Navy 2014)

[xxix] (Comcercial Crime Services 2014)

[xxx] (Marshall 1993)

[xxxi] (Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force 1981, 193-258)

[xxxii] (Corcoran 2014)

[xxxiii] (Clarke, Carriers; Fully Loaded – Admiral Kuznetsov 2009)

[xxxiv] (naval-technology.com 2014)

[xxxv] (Royal Navy 2014)

[xxxvi] (Farmer 2014, Bannister 2014, Royal Navy 2014), a similar incident took place with Australia in 2014, when a Russian Task Group positioned itself in international waters to the north of the country – requiring the response of multiple Royal Australian Navy ships (LaGrone, Australian MoD: Russian Surface Group Operating Near Northern Border 2014, Dean, Lee and Noble 2014, BBC 2014, Dearden 2014, Pearlman and Parfitt 2014).

[xxxvii] (defenceweb 2014)

[xxxviii] (Chinese Military Review 2013)

[xxxix] (Rahmat and Hardy 2014)

[xl] (Clarke, October 2013 Thoughts (Extended Thoughts): Time to Think Globally 2013)

[xli] As the Egyptian Navy itself discover recently when a patrol boat engaged what are presumed to have been smugglers (LaGrone, Egyptian Patrol Craft Attacked by Ships with Possible Ties to Terrorist Arms Trade 2014)

[xlii] (Beaumont 2014, Paul Bremer III and Sonnenberg n.d., Council on Foreign Relations 2013)

[xliii] In fact it seems to have taken place whilst this work was being written, (LaGrone, Egyptian Patrol Craft Attacked by Ships with Possible Ties to Terrorist Arms Trade 2014)

[xliv] Some nations seem to already be taking this in to account, for example the Dutch Holland Class (navyrecognition.com 2013) and the Danish Knud Rasmussen Class (naval-technology.com 2014)

[xlv] (navyrecognition.com 2013)

2 thoughts on “Protecting the Exclusive Economic Zones – Part I”