Territorial conflict has been a continuing problem in South America and is often related to the possession of natural resources that represent a considerable income to the countries in dispute. On January 27, 2014, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) gave its verdict on a case brought before the court in 2008 by Peru, which asserted a territorial claim on approximately 38,000 sq km of the Pacific Ocean bordering with Chile. The court ruled in Peru’s favour, in a judgment that was widely regarded as fair.

This is not the first confrontation between Peru and Chile. “Guerra del Pacifico” War of the Pacific (1879-1883) was a well-known conflict between both countries and resulted in the annexation of valuable disputed territory on the Pacific coast. It grew out of a dispute between Chile, Peru and Bolivia over control of a part of the Atacama Desert located between 23rd to 26th parallels of the South American Pacific coast, known for an abundance of mineral resources, particularly sodium nitrate.

After years of confrontation between the three countries, Chile and Peru signed the Treaty of Ancón relinquishing the Province of Tarapacá as well as the departments of Arica and Tacna to Chile in 1883. These territories would remain under Chilean control, however, the two nations were unable to agree on how or when to hold the plebiscite, and in 1929, both countries signedthe Treaty of Lima, in which Peru gained Tacna and Chile maintained control of Arica. Even though Peru regained Tacna, some fishing dominions were given to Chile thereby angering Peruvians financially dependent on artisanal fishing. Diplomatic relations between the two nations have consequently remained tense for many years.

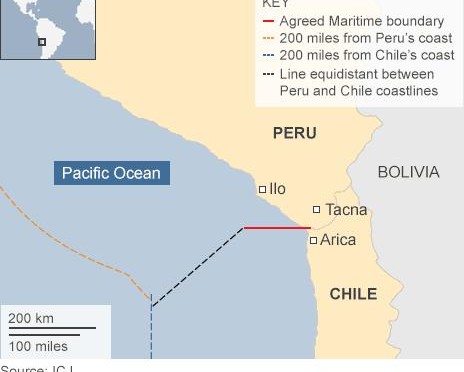

Today both countries are once again disputing, this time in relation to claims on maritime territories. The issue was brought to the fore in 2008 when Peru filed the claim at the International Court of Justice in The Hague that marine boundaries had never been formally agreed upon by the two countries and needed objective international approval. In its defense, Chile posits that the line had been defined in agreements signed in 1952 and 1954, which Peru argued were strictly fishing accords.

After 5 years of tension, the court has finally ordered that the common marine border be redrawn to follow the current border for 80 miles from the coast but then will veer southwest for 120 miles, giving Peru the disputed “external triangle.” The current border runs due west from the coast for a full 200 miles, a demarcation that Chile has enforced since it won the Pacific War with Peru and Bolivia.

In a statement issued after the verdict was announced, Peruvian President Ollanta Humala said “Peru is pleased with the outcome” of the court’s decision, and would “take the required actions and measures immediately for its prompt implementation.” The Peruvian government also said that the decision applied to nearly 19,000 square miles of offshore territory, or more than half of the 37,000 square miles it originally sought. Peru’s fishing industry estimates that the disputed zone has an annual catch of 565m Peruvian nuevo soles ($200m; £121m), particularly of anchovies which are used to make fishmeal. Peru will also gain access to some extra swordfish, tuna and giant squid.

Peru’s victory will not only significantly increase income in its fishing industry, but will also go a long way in restoring nationalism after a humiliating defeat to Chile in the 19th Century.

Alternatively, Michelle Bachelet, who will assume the Chilean presidency in March, stressed that even though Chile had lost none of its territorial waters (which extend for 12 nautical miles from the coast), the ruling is a “painful loss” considering the importance of this external triangle. As a condition for implementing the agreement representatives from the government of Chile have also suggested that Peru sign an International Convention on the Law of the Sea and accept the line through Hito 1 as its land border (losing 350 meters of beach); an agreement Peru remains reluctant to address, hoping instead for swift implementation of the ICJ’s verdict.

Andrea was born in Bogota, Colombia, and immigrated to Canada in 2006. She graduated in June 2012 from York University with a Bilingual BA in International Studies. After finishing her BA, she moved to Geneva, Switzerland, where she had the opportunity to do an internship with the World Health Organization (WHO). She is pursuing a Double Master in Public Policy and Human Development at the University of Maastricht, Holland. This article was re-published by permission and appeared in original form at The Atlantic Council of Canada.