By Ambassador Bernard Goonetilleke and Admiral Dr. Jayanath Colombage

The Indian Ocean

The economic, strategic, and ultimately political importance of the Indian Ocean has been recognized for centuries. Mariners from Arabia, East Asia, and the Pacific, while plying their trade, studied weather patterns in the Indian Ocean and explored and traversed it regularly, laying the foundation of the rules of orderly maritime conduct. Intrepid mariners from Europe ventured through the Indian Ocean to the furthest reaches of East Asia and the Pacific in search of spices, as well as land and treasure to be acquired for their patrons, adding to the corpus of rules and practices that would become, over time, the Law of the Sea.

Today, the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean are home to some 2.7 billion people, or some 35 percent of the world’s population. The Indian Ocean provides vital access to the powerful economies of South Asia, East, and Southeast Asia, including supplies of energy from countries of the Persian Gulf and Africa. Some 70 percent of world trade and 50 percent of crude oil reaches their destinations through the Indian Ocean. More than 80 percent of the world’s maritime trade in crude oil passes through the chokepoints of the Indian Ocean, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 8 percent via the Bab el-Mandeb, and 35 percent through the Straits of Malacca.

Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean

Sri Lanka’s geographically central location and its proximity to the major sea routes traversing the Indian Ocean may have inspired the nation’s political leaders to be proactive in initiating, from time to time, imaginative and broadly conservationist measures to protect and preserve this Ocean’s resources, as well as their concern that peace, order, and good governance be maintained among the communities that surround it to promote their well-being.

Thus, in 1971, at the initiative of Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike, later joined by the President of Tanzania, the United Nations General Assembly declared:

“The Indian Ocean, within limits to be determined together with the air space above and the ocean floor subjacent thereto … designated for all time as a Zone of Peace.” (A/RES/2832 (XXVI)

Adopted by the General Assembly at its 26th Session by a vote of 61 in favor and none against, but with some 55 abstentions, the Declaration called on the “great Powers” (a) to halt further escalation and expansion of their “military presence” in the Indian Ocean, and (b) to remove from the Indian Ocean all fixed elements of their rivalry, such as military bases, installations and logistical supply facilities, and even warships and aircraft, to the extent that they were intended to maintain a “military presence” in the area, and were not merely in transit on their lawful occasions. Implementation of the Declaration was to be through conclusion of an international agreement that would include (1) prohibition of the use of ships and aircraft against the littoral and hinterland States of the Indian Ocean in contravention of the U.N. Charter; and (2) guarantee the right of ships and aircraft of all nations, whether military or other, “free and unimpeded” use of the Indian Ocean and its airspace in accordance with international law. Efforts to implement the Declaration by its proponents supported by the Non-Aligned Group and some other States continued within the U.N. General Assembly until by the close of the Twentieth Century. Since then, such efforts seemed to have lost all momentum.

While the “great power rivalry” that caused concern in the 1970s might have receded, new developments of concern and the prevalence of illegal and criminal activity in the Indian Ocean moved President Maithripala Sirisena, when addressing the States of the Indian Ocean Rim at the Group’s Twentieth Anniversary Meeting in Jakarta in March 2017, to call on them to work out a stable legal framework that would put an end to trafficking of illicit drugs and other criminal activity in the Indian Ocean, while maintaining freedom of navigation in accordance with international law.

In February 2017, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, in an address at Deakin University in Australia, expressed concern that the post-Cold War multi-polar world had brought about “A massive transition of economic and military power to Asia within the Indian Ocean and the Pacific” and he concluded that, “the global political order, which produced the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is radically different from the current global dynamics…” He warned that “current agreement ambiguities could generate global economic disruption,” and said “The ideal solution for the Indian Ocean is for all parties to agree on a code of conduct for military vessels traversing the Indian Ocean” and that “the Code on the Freedom of Navigation in the Indian Ocean must include an effective and realistic mechanism on dispute resolution…” He concluded saying “any agreement, also needed to recognize the escalation in human smuggling, illicit drug trafficking and the relatively new phenomenon of maritime terrorism.”

The need to keep the vital sea lanes open for all and to maintain peace and stability in the Indian Ocean Region, and ensure the right of all states to the freedom of navigation and overflight, was expressed by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe once again at the 2nd Indian Ocean Conference held in Colombo in September 2017.

Meanwhile, at the same event, the Indian External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj said “The Indian Ocean is prone to non-traditional security threats like piracy, smuggling, maritime terrorism, illegal fishing, and trafficking of humans and narcotics. We realize that to effectively combat transnational security challenges across the Indian Ocean, including those posed by non-state actors, it is important to develop a security architecture that strengthens the culture of cooperation and collective action.”

While waiting for further developments in the South China Sea negotiations between the ASEAN and China, as well as negotiations between the U.S and China relating to safety in the air and maritime encounters that could serve as inspiration to the 21 States currently members of IORA, the Pathfinder Foundation offers herewith a preliminary draft of a Code of Conduct aimed at organizing cooperative efforts to take action to meet security challenges in the Indian Ocean, including those posed by non-state actors. The draft which, where appropriate, follows the structure of Codes of Conduct designed for East Africa (Djibouti Code of Conduct) and West Africa (Yaoundé Code of Conduct) concluded under the auspices of IMO, is offered for review and comment.

View the draft Code of Conduct below or download here. Please submit your input and recommendations to [email protected].

Pathfinder Foundation Indian Ocean Code of ConductA “Code of Conduct,” as commonly conceived, is not a legally binding document, but would prescribe rules to be observed in organizing cooperation in the pursuit of a common set of objectives. It should be noted that, in contrast, the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea which is legally binding on States Parties to it, include the States participating in the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). The Pathfinder Foundation commenced the New Year by inaugurating its Centre for the Law of the Sea (CLS) in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The draft Code of Conduct for the Indian Ocean was created to assist consideration of the idea by the 21 littoral States members of the ‘Indian Ocean Rim Association’ (IORA).

Through an inclusive process and cooperative engagement, a Code of Conduct may be devised and disseminated to further enhance peace and prosperity in the Indian Ocean.

A graduate in History and post graduate in International Relations (The Hague), Bernard Goonetilleke spent nearly four decades as an officer of the Sri Lanka Foreign Service. He took over the post of chairmanship of Sri Lanka Institute of Tourism and Hotel Management (SLITHM) in August 2008 and later appointed as Chairman of Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA) and Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB) with effect from November and December 2008, respectively until February 2010. His career as a Foreign Service officer began in 1970 and has included postings to Sri Lanka diplomatic missions in Kuala Lumpur, New York, Bangkok, Washington D.C., Geneva and Beijing. He held several positions in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs including Director General (Multilateral Affairs) (1997-2000) and ending as Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2003-2004). During his career, he served as Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the UN in Geneva (1992-1997), during which period he was concurrently accredited to the Holy See and as Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations in Vienna. Later he served as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China (2000-2003), during which assignment he was concurrently accredited as Ambassador to the People’s Republic of Mongolia and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. He also served as Acting Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the UN in New York (2004-2005) and ended his diplomatic career as Ambassador to the United States of America (2005-2008). Following the signing of the Ceasefire Agreement between the Government and the LTTE in 2002, he headed the Secretariat as Director General of the Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP) and functioned as one of the four members of the government negotiating team. Mr. Goonetilleke functions as Chairperson of the Pathfinder Foundation since 2010.

Admiral (Dr.) Jayanath Colombage is a former chief of Sri Lanka navy who retired after an active service of 37 years as a four-star Admiral. He is a highly decorated officer for gallantry and distinguished service. He is a graduate of Defence Services Staff College in India and Royal College of Defence Studies, UK. He holds a PhD from General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University. He also holds MSc on defence and strategic studies from Madras university and MA on International Studies from Kings college, London. He is a visiting lecturer at the University of Colombo, Defence Services Command and Staff college (Sri Lanka), Kotelawala Defence University, Bandaranaike Center for International Studies and Bandaranaike International Diplomatic Training Institute. He was the former Chairman of Sri Lanka Shipping Corporation and an adviser to the President of Sri Lanka on maritime affairs. He is a Fellow of Nautical Institute, London UK. Admiral Colombage is currently the Director of the Centre for Indo- Lanka Initiatives of the Pathfinder Foundation. He is also a member of the Advisory council of the ‘Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka.’ And a Guest Professor at Sichuan University in China.

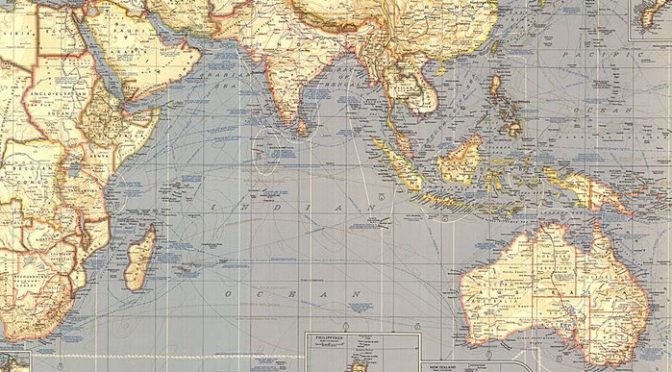

Featured Image: 1941 map of Indian Ocean (National Geographic)

Excellent initiative with positive impact regionally as well as internationally