By Steve Wills

Introduction

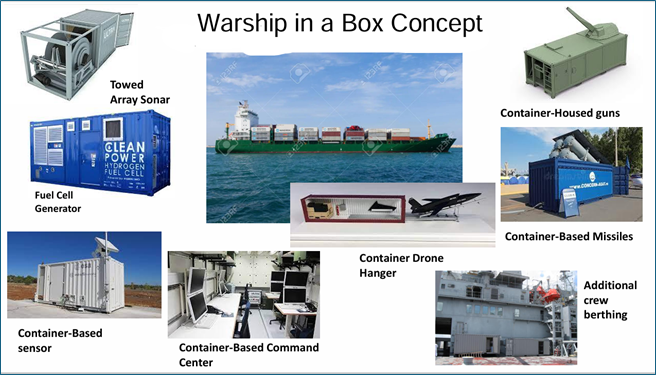

Naval vessels of all types have grown over the past 50 years. Even relatively low-end warship classes, such as the littoral combat ship, possessed significant system complexity. The tilt towards increasing warship complexity occurred before the mid-20th century. Arguably, the warship significantly diverged from its civilian, merchant counterparts around the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865), the last major conflict the U.S. converted large numbers of commercial vessels into front-line warships. At the time, one could merely provide a naval crew and mount a few guns onto a merchant ship to create a relevant warship. While that level of simplicity has long passed, technology has again made it possible to use elements of the commercial maritime system to quickly create functional warships. The ubiquitous shipping container, equipped with everything from cruise missiles to towed array sonars, generators, berthing, and command spaces, allows for the conversion of any container-capable commercial ship into a combatant.

These conversions do come with limitations in speed and especially the ability to sustain and recover from damage. That said, the “warship in a box” concept offers navies the ability to create combatants of different sizes and capabilities rapidly, from smaller offshore resupply ships with only a couple of containers to large “missile merchant” vessels depending on the number and types of container-based systems fitted.

Making Warships from 1775 to 1865

The United States Navy began in October 1775 with the basis of its fleet consisting of converted merchant ships. A squadron of ships composed of the vessel Alfred, with 24 guns, and the eight gun schooners Wasp and Fly, formed the first combatant formation. The squadron was responsible for capturing British military supplies in Nassau. Most of the Continental Navy was merchant-based until Congress authorized the first thirteen purpose-built frigates in December 1775. John Paul Jones’ famous vessel, Bonhomme Richard, was a heavier type of cargo vessel class, an East Indiamen that featured strengthened decks to carry a gun armament for self-protection on the trade routes.

By the 1790s and early 1800s, the U.S. Navy was known for its powerful frigate warships, yet it still retained the option to expand its fleet in war through the commissioning of armed merchant vessels as combatants. This practice continued up to and expanded during the Civil War, with the Union Navy expanding 15-fold in numbers, primarily through converted merchant ships. The Brooklyn Navy Yard alone refitted 190 merchant ships as warships and completed one such refit (USS Monticello) in just 24 hours.

While converted merchant ships arguably helped win the Civil War through their use as blockade ships, a combination of technological changes during the Civil War made converted merchant warships far less useful. Heavy rifled guns, armored steel plates, and steam-powered machinery created a new kind of warship that civilian conversions could not easily match or contest. Warships had to be designed to support armor and heavy guns, now mounted in heavy armored turrets. Modern armaments and protective armor could not be easily added to an existing commercial ship.

Gradually, the merchant warship disappeared, although some high-speed ocean liners went to sea with the provision to mount medium-caliber guns to serve as “merchant cruisers” for sea lane patrol and raiding. However, these vessels were no match for purpose-built warships, and the submarine largely assumed the role of raiding naval platforms. The end of the merchant cruiser is perhaps symbolized by the sinking of the British-armed merchant cruiser, HMS Jervis Bay, by the German “pocket battleship,” Admiral Scheer, on November 5th, 1940, in less than 30 minutes of combat.

Return of the Merchant Warship

Unlike the 1940s, today’s merchant ships are often much larger than their warship counterparts. The sheer size of merchant vessels offers some degree of protection through plenty of reserve buoyancy and is resource-friendly by requiring just a handful of sailors to crew them. The introduction of the shipping container in 1956 by American businessman Malcolm McClean effectively invented container intermodalism in the commercial maritime world. Most commercial goods are moved by shipping container, whether by sea, truck, or rail transportation. Russia has already weaponized the shipping container, and perhaps the Chinese as well with containerized cruise missile launchers.

The concept is that an armed merchant ship might serve as a hidden raider or provide defense against seizure by an adversary. For the United States, the growing number of containerized systems, including cruise missiles, suggests a return to a pre-1865 period when commercial ships could be rapidly converted into effective warships. The shipping container’s many forms become the basis for returning to a merchant warship armed with modern weapons capable of fighting and sinking purpose-built combatants.

What types of systems can be containerized for combat?

While shipping containers fitted with missiles have captured most of the attention, many other variants exist that could serve to create a containerized warship. Finnish defense contractor Patria created a 120mm gun system that fits within a shipping container. The weapon box contains 100 rounds of ammunition, requires a crew of three to operate, is self-contained with air conditioning, and resists chemical/biological/radioactive (CBR) agent penetration.

Anti-submarine warfare systems can also come as containerized packages. Atlas-Electronik makes a two-container, plug-and-play, towed array sonar system complete with operator consoles in one of the containers. Loitering drone munitions are another option. German defense contractor Rhinemettal makes a modified shipping container with 126 launch cells for the Hero loitering munition (suicide) drone. Other containerized applications include secondary weapon systems, additional sensors, data storage, medical facilities, and control spaces. Containerized generators offer energy solutions for powering these systems. Containers can also house combat information centers and additional crew berthing.

Pulling Containerized Systems into a Warship in a Box

Containers are the basis of goods movement globally, available in numbers and able to fit on a wide range of vessel types and sizes. Containers with military capabilities can be hardwired together to form a complete system or connected with Wi-Fi in some applications to reduce vulnerability to connection loss due to battle damage.

The modular nature of containerized warships means that training can occur on or off the ship platform. The warship-in-a-box system can be exercised ashore on a pier just as easily as at sea. Given this feature, it might be a good concept for the Naval Reserve to embrace for rapid integration into the fleet. Naval Reserve units located at inland sites could still train with their containers and have regular transportation to port facilities for embarkation on suitable ships for at-sea exercises.

The containers that comprise “Warship-in-a-Box” would be loaded onto an appropriate-sized civilian-built ship, from an offshore resupply vessel to a Panamax container ship in size, and crewed with a Navy complement of sailors approximating the crew of comparable civilian vessels. The idea is to keep the crew size to a minimum to save costs and maximize the number of container warships that can be created. The ship can be painted a haze grey or leave it in merchant livery as a “Q-ship” if desired. Finally, commission it with the appropriate USS Ship Name.

Unlike traditional warships requiring individual weapon system reloads, the warship in a box is defined by its self-contained, containerized capabilities. Warships require specialized equipment and facilities for replenishment of weapons in port. The potential underway reloading of missiles is several years away and still being tested. The warship-in-a-box concept simplifies reloading with containerized systems that can be installed on ships with existing equipment in container ports around the United States. Safety precautions, especially for weapons susceptible to electromagnetic energy, remain a concern. Still, ports worldwide can handle containerized systems with relative ease, unlike purely naval ports, where conventional warships are replenished. This greatly expands the scope of available infrastructure and equipment that can contribute to containerized capabilities.

Like current uncrewed navy ships that are starting to exploit containerized weapons, the warship-in-a-box concept would be deployed for exercises and some contingencies, but would essentially be a “break glass in the event of war” capability to rapidly augment the fleet with additional vessels for warfighting missions depending on numbers and types of containers embarked. They could range in size from large container missile arsenal ships with dozens or hundreds of weapons to offshore resupply ships with only four to six containers supporting one or two basic missions. The Navy has already experimented with shipping container weapons on conventional warships, so moving to a vessel with all capabilities housed in containers is a logical next step.

Drawbacks to the Warship-in-a-Box

While the concept can rapidly bring together the capabilities of a frigate-sized ship, both the host platforms and containerized systems have numerous weaknesses that conventional warships do not possess. Most commercial ship platforms that could host a container-based system are slow, with speeds of only 13 to 16 knots, and are often unsuitable for fleet operations. There would be little to no redundancy in systems or people, features that characterize conventional warships. They are effectively auxiliary warships like the many converted commercial craft seen in world navies into the mid-19th century, but armed with lethal fires and capable of inflicting significant damage on an opponent at relatively low cost and personnel.

Conclusion

The warship-in-a-box program is not a substitute for purpose-built warships that are globally deployable and commanded by national leadership. However, a force of these units in the hands of the naval reserve could be a quickly deployable and operational group of second-tier units for patrol, escort, and even strike operations given the potential size of their missile magazine. Any conflict with a peer opponent would be global, and historically navies find that they never have enough ships to cover all tasks that surface in the course of a major conflict. Using the shipping container, the building block of the maritime world, represents a relatively quick and easy method of creating additional naval capacity to improve warfighting advantage.

Dr. Steven Wills is a navalist for the Center for Maritime Strategy at the Navy League of the United States. He is an expert in U.S. Navy strategy and policy and U.S. Navy surface warfare programs and platforms. His research interests include the history of U.S. Navy strategy development over the Cold War and immediate, post-Cold War era, and the history of the post-World War II U.S. Navy surface fleet.

Featured Image: A containership at port. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Our likely adversary will have a massive advantage in terms of box ships and we will likely need those we have or can obtain to move actual cargo. Tracking such ships will be easy. The U.S. strength in our fleet in being and potential for fast builds of useful ships lies in those fast supply vessels and patrol boats we use for FMS programs. We could quickly have a massive manned/optionally manned/unmanned fleet with numbers that can deter China’s “surface game.”

Adding containerized systems manned by Navy Reservists to Coast Guard cutters could allow rapid upgrade to near frigate capabilities with fewer disadvantages than merchant ships.

They already have Navy standard sensors, communications, and ESM.

A slow. containerized missile ship will essentially be defenseless. Particularly against enemy submarines or massed bomber raids.

It would be nice if it were small, fast, shallow draft and maneuverable such it could hide and blend into an Island with the Marine stand in forces.

You know we can stick a helicopter with ASW equipment just saying.

Witness this now 9 year old video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=81E41ZEKi0g