Kilmeade, Brian, and Don Yaeger. Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates: The Forgotten War That Changed American History. New York City: Sentinel, 2015, 256 pp. $21.00

By Commander Greg Smith, USN

Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates is an exciting account of an often overlooked but formative chapter in the history of American foreign policy and U.S. naval heritage. While even amateur naval historians recognize the names of heroes like Decatur and Preble, and every Marine sings the words “to the shores of Tripoli” while standing at attention, few recall the decade-long struggle and humiliations endured before achieving the honorable outcome that is taken for granted today. As the world’s sole superpower with a naval force of nuclear powered aircraft carriers and submarines, it is often difficult to examine the early struggles of the United States Navy without assuming that victory was a foregone conclusion. Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger, however, convincingly convey the narrow margin by which the victory over the Barbary pirates was gained and the many diplomatic, military, and personal setbacks that were overcome along the way. They also capture the bravery and determination of the American Sailors, Marines, and Statesmen who ensured a favorable conclusion of the Barbary Wars for the nascent United States. For these reasons alone, Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates deserves to be on every commander’s recommended reading list for all ranks, especially in the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.

The book also explores several themes that are of recurring interest to CIMSEC’s readership: from justifications for force structure and naval presence, to the need for judgment and initiative in naval leaders, and to the role of the Navy in diplomacy. The thoroughly enjoyable book makes strong arguments for U.S. naval presence and the need for the United States to a “play a military role in overseas affairs,” without significant discussion of counter-arguments or allusions to alternative analyses. Although this may ultimately leave military historians and other scholars and theorists unsatisfied, these shortcomings seem to be by design, enabling the authors to maintain an exciting pace and to focus on the heroism of the characters from whom “the world would learn that in America failure is not an option.”

Naval Presence and the Size of the Fleet

Kilmeade and Yaeger make a strong case that Thomas Jefferson was among the first American officials to recognize the need for a strong and persistent forward naval presence to protect American interests. In his role as American minister to France in 1785, Jefferson was an official advocate for Americans enslaved by Algerian pirates. He recognized that the United States could neither afford the tribute demanded by the Barbary States, nor could they cease trading with nations of the Mediterranean. Jefferson’s solution was patrols by armed American vessels in the Mediterranean; that vision would not be realized for another sixteen years. Initially, Jefferson did not convince fellow diplomat John Adams, Congress, or the President, who were pursuing a policy of neutrality and willing to pay the price (i.e. annual tribute to Barbary pirates) for peace. It was not until ten American vessels were captured in 1793 that there was enough support to pass the Naval Act of 1794 to build six frigates to respond to the “depredations committed by Algerine corsairs.”

Although the more academically sophisticated arguments for seapower made by Samuel Huntington[1] in 1954 or more recently by CAPT Robert Rubel (ret) [2] and Seth Cropsey will be more edifying for CIMSEC’s regular audience, the arguments in Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates are self-evident, convincing, and accessible even to those who have shown little interest in strategic or maritime thinking. Thus, the book is a worthy read not only for the naval enthusiast but also for the accountant brother-in-law who balks at the Navy’s shipbuilding budget, to the family isolationist who argues that U.S. naval presence is always provocative and never stabilizing, or for the West Point graduate who just doesn’t get it.

Naval Leadership

Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates provides many case studies on naval leadership. The book examines many successful and unsuccessful commanders and diplomats who must carry out national policies and execute military operations with little communication and guidance.

While it is rare to execute any coordinated action today without communication before, during, and after each mission, the authors remind us that orders from the United States to commanders in the Mediterranean routinely took three months to arrive in theater. This made seeking guidance during a crisis, like the grounding of the USS Philadelphia in Tripoli harbor, impossible. Incidents like these formed the basis for naval principles like the absolute responsibility of commanding officers, the requirement to understand the commander’s intent, and centralized command and decentralized execution that continue to serve as the foundation for naval conduct. Looking at the 21st century battlespace, where instantaneous and continuous communications are often assumed for our naval and air forces, it is worth pondering how well we still adhere to these principles and how much decision making and execution would suffer should those communications be disrupted in combat. Kilmeade and Yaeger make clear that in the absence of higher guidance those who represented the country well were those guided by a commitment to personal and national honor.

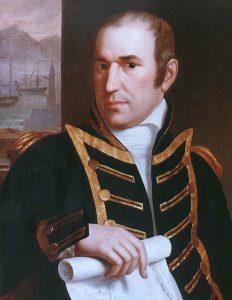

The authors also assert that throughout the Barbary Wars, successful naval leaders demonstrated superior judgment and initiative. The authors contrast the risk-averse and lazy Commodore Richard Morris, who brought his wife on deployment and failed to impose a worthy blockade of Tripoli, with the decisive actions of Commodore Edward Preble, who quickly gained an “honorable peace” with Morocco, achieving a “significant victory” in a manner reminiscent of Sun-Tzu—“without firing a shot.”

The authors also recount the bold manner with which Preble overcame the loss of the USS Philadelphia by a subordinate commander. Preble and the young nation found an invaluable asset in the bravery, skill, and leadership of Lieutenant Stephen Decatur. The leadership, persistence, and vision of William Eaton are credited with the successful execution of the elaborate plan to raise and march an army from Alexandria, Egypt to defeat the Bashaw of Tripoli. The success of Eaton’s 600-mile desert march that resulted in capture of the city of Derne, “one of the most remarkable military assaults in U.S. military history,” was in no small part due to the bravery and skill of Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon and his seven U.S. Marines.

Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates provides a fresh look at leaders whose actions significantly shaped the character of the nascent Navy and Marine Corps and whose impact is still visible today. The book also recalls some of the earliest collaboration between military power and diplomacy in the implementation of U.S. foreign policy.

Diplomacy and the Military

Kilmeade and Yaeger recount the first attempt to support diplomacy with a display of naval power in 1800, when the USS George Washington became the first American warship to enter the Mediterranean. In spite of the bolstered confidence of U.S. Consul to Algiers, Richard O’Brien, and the clear display of American resolve, the incident resulted in humiliation for the United States due to a combination of insufficient force and naiveté on the part of the George Washington’s commander, the 27-year old Captain William Bainbridge. Still, naval forces represented a level of commitment and national resolve that provides significant leverage for diplomatic efforts.

As with the U.S. consuls to the Barbary States 200 years ago, diplomats today are often strong proponents of American naval power. In February, a former U.S. Ambassador to Singapore argued that cutting the number of Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) would damage U.S. diplomacy. Of course, the requirements for fighting a modern naval battle are often different than those for diplomatic shows of the flag, assurances to allies, and demonstrations of resolve. Still, even when the latter was the primary justification for the existence of the fleet in 1794, getting the right-sized force was a significant challenge. Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates also demonstrates that, in addition to the right number of ships, success requires the right policies and military leadership to successfully support diplomatic efforts.

The book also highlights a natural tension between military and diplomatic elements of national power through its account of the termination of the war with Tripoli in 1805. After achieving an impressive victory at Derne, Colonel William Eaton and Lieutenant O’Bannon prepared to take Tripoli to depose the Bashaw. Before they could do so, however, U.S. Consul Tobias Lear, negotiated a termination to the conflict with terms that were ultimately ungratifying to Eaton, the military commander whose men had sacrificed much blood for a peace that allowed the Bashaw to remain in power.

Although the authors’ treatment of the relationship between military power and diplomacy seems to suggest that the solution to bolstering diplomacy is always more military power, one does not have to accept that premise to appreciate the books’ account of early cooperation to achieve U.S. foreign policy objectives.

Few today recall the risks that were taken by the men of the naval and diplomatic services to defend the honor of the young United States against the extortion of the Barbary pirates, but Brian Kilmeade and Don Yaeger do a great service by remedying that situation. At the time that Thomas Jefferson was dealing the pirates from the Barbary States – Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli—the confrontation was far from a foregone conclusion. Thomas Jefferson and the Tripoli Pirates details how visionary leadership from Thomas Jefferson, William Eaton, and Edward Preble as well as the bold and daring initiative from Stephen Decatur and Presley O’Bannon enabled the young United States to prevail. The story explores the connection between naval presence and security, illustrates the need for judgment and initiative in executing distributed military operations, and the role of the Navy in foreign policy. It is worth reading and keeping on your bookshelf.

Commander Smith is a career naval flight officer and a former commanding officer of Patrol Squadron 26 (VP-26). He is currently serving as the Federal Executive Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University – Applied Physics Lab (APL). The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the views of the Navy or APL.

[1] Huntington, Samuel P. “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Vol. 50, Number 5. May 1954, 491.

[2] Rubel, Robert C. “National Policy and the Post-systemic Navy,” Naval War College Review Vol. 66, No. 4 Autumn 2013, 12.

A great review by a respected Naval Officer. In reading this book I was often reminded of how long it takes to learn what works and how often we seem to have to relearn the same thing.

CAPT Tom Colyer, USN, (ret)