By Matthew Hipple and Michael DeBoer

The military has two masters – the executive, who directs and operates, and the legislature, who regulates and budgets. The Navy, and other services to a lesser extent, have forgotten that obedience to the executive branch exists alongside, not above, congressional oversight – to which the military owes its total independent honesty when directed. Generations of centralizing service functions under the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and Joint Staff erroneously encouraged the services to dispose of their independent advocacy. In advocating the budgets and plans OSD orders for execution, the dialogue between civilian government and the military becomes civilian government’s dialogue with itself, lacking the professional advice from those promoted and positioned to provide it – in particular to a Congress owed that candor in public testimony. This crisis in civil-military (civ-mil) relations and institutional inertia demands professional and courageous leadership to correct.

National Security Act of 1947

While civil-military decision-making in a healthy Republic rightly defers to civilian policymakers, the executive constraints imposed on the armed forces by congress throughout the Cold War have disrupted effective civil-military dialogue. The National Security Act of 1947 assigned the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) as the primary advisor to the President on military affairs. This diminishment of service access to the President gradually suppressed the forceful yet necessary presentation of different and dissenting perspectives. President Eisenhower still felt obliged to at least negotiate through his Staff Secretary written support from the Joint Chiefs for the “New Look” and a constrained 1958 budget. In 1960, CNO Admiral Arleigh Burke still fought his way to presenting Eisenhower the Navy’s counterargument to joint nuclear targeting. But by the Johnson administration, the independent culture of the Joint Chiefs had waned – the service chiefs remained publicly silent on Vietnam policy while relying solely on JCS Chairman General Earle Wheeler, who failed to forcefully present their escalating concerns to President Johnson. Voluntarily and structurally, service access to civilian policymakers withered – decreasing the presence of dissenting opinions and driving down the quality of advice and insight to the President and Congress.

This compares unfavorably with civ-mil dialogue before the National Security Act. During World War II, Fleet Admiral Ernest King forced dissenting opinions onto the Combined Chiefs of Staff, at times even upon Allied heads of state. His forcefully argued views aided Allied strategic planners. His feud with Winston Churchill prevented expansion of the Mediterranean Campaign and contributed to the conclusion of Douglas MacArthur’s self-indulgent Southwest Pacific Campaign – wasteful efforts undermining American interests.

The National Security Act limited exposure to dissenting opinions – constraining military advice, independent thought, and critical argument. However, the mechanisms of Presidential advice did not relieve service chiefs of their advisory role to Congress. General Wheeler’s contemporaries chose to rely on Wheeler rather than communicate their professional judgement to the legislature. Conversely, in an act of supreme leadership and professionalism, General Eric Shinseki risked his career and sacrificed his influence in 2003 by providing Congress his frank assessment of troop requirements for postwar occupation of Iraq – views that clashed directly with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and OSD. General Shinseki’s assessments were professionally accurate and procedurally proper, presented to Congress in official testimony where his honest insight was demanded. Career risk is inherent in positions of service leadership, but Shinseki understood his tenure was more expendable than his candor. Three years later, CENTCOM Commander General John Abizaid testified before Congress that “General Shinseki was right…”

February 25, 2013 — Less than a month before the start of the Iraq War, Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki states that several hundred thousand troops may be required to secure Iraq after initial combat operations. (CSPAN Video)

Congressional Budget Act of 1974

The Congressional Budget Act of 1974 eliminated service chiefs’ formal development of independent budgets. Prior to the act, each department presented and defended their service budget requests before Congress. This allowed significant discourse between service chiefs and Congress on substantial matters of service health, acquisitions, and doctrine. Services drove operational innovation through their budgets, from Admiral Burke’s broad revolution introducing multiple high-end ship classes like guided missile frigates and cruisers, ballistic missile submarines, and nuclear carriers to Admiral Elmo Zumwalt’s High-Low Mix concept. The budget act suppressed these service innovations. Since 1974, the only doctrinal innovation conceived and planned by a service and funded by Congress was AirLand Battle. Now services primarily focus on continued access to funding for existing programs of record, rather than driving innovative operational concepts or abandoning failures.

The budget act delegated part of Congress’s responsibility to raise an Army, provide and maintain a Navy, and regulate both services. With resourcing and budget debates seemingly ceded to an executive branch that already controls military operations, the services mistake their perception and advisory duties as also subordinate to the executive branch. The military’s activity shifted from mere loyal execution of executive branch policies to self-imposed advocacy for the executive branch’s policy as well. This put service chiefs in the unfortunate and awkward position of defending budgets they may consider damaging. Instead of robust discourse, hearings became matters of course, with service chiefs falling on the swords of top-line budgets outside their control.

However, the act’s change in budget development did not relieve service leadership of their duty to advocate for realistic needs or to articulate the operational risks of underfunding. Although not a service chief, Commander, Surface Forces (SURFOR), Vice Admiral Thomas Copeman frustrated service leadership for his public candor on the surface fleet’s operational decline in 2013. Admiral Copeman honestly and publicly described the surface force’s readiness challenges, including warships’ loss of range and lethality, and the fragility of logistics at sea. He criticized programs openly, and backed these concerns with resource requests and actionable concepts:

“It’s getting harder and harder, I think, for us to look troops in the eye and say, ‘Hey, just do it and meet the standard’…You’ve got to make choices…And if it was my choice—and it’s not only my choice—I’d give up force structure to get wholeness.”

Now, even when offered the chance to advocate for more resources by Congress, the Navy declines while in the same assessment acknowledges repairs or replacements for cruisers are unaffordable.

Admiral Copeman helped pave the way for the Distributed Lethality concept of operations — accelerating modular weapons deployment, defenses for naval auxiliaries, and improved autonomy for at-sea commanders in a communications-denied environment. Although Distributed Lethality faded in a service “narrative correction,” towards centralization, Admiral Copeman’s work accelerated reform, weapons acquisition, and procurement of the Constellation-class frigate. But for simple, effective acts of candor he was sarcastically dubbed the “Sea Lord” for bucking the agreed OSD narrative – a moniker those who understood the crisis knew was unintentionally complimentary. Expending his own forward career momentum on his service’s future, Admiral Copeman did his duty as the leader of the surface community.

Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act of 1986

The Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 hammered the final nail in robust military advice’s coffin. The act strengthened combatant commanders (COCOMs) at the expense of the service chief’s power of maintenance and budgetary management already reduced by the Budget Act. Prior to Goldwater-Nichols, the Joint Chiefs functioned as a check on the operational decisions of combatant commanders, as when the chiefs expressed significant reservations regarding General MacArthur’s plans to expand the Korean War. The Joint Chiefs eventually supported MacArthur’s relief and their blunt testimony to Congress supported President Truman’s decision to fire a nationally popular and politically-connected household name. Unfortunately, COCOMs now receive relatively little oversight in execution of their operational functions. Attempting to provide oversight to CENTCOM General Tommy Franks’ Iraq invasion war plans was yet another moment of sacrificial professionalism that cost General Shinseki influence as Army Chief.

Further, Goldwater-Nichols removed the linkage between operations and acquisitions. Prior to the act, service chiefs managed the breadth of their services obligations, ensuring that a ready, able, and well-trained force could execute its global responsibilities. Goldwater-Nichols ensured that resource-unconstrained COCOMs could request forces not in existence, forcing the service chiefs to attempt to meet requests for operational forces their services could not safely generate. When services decline to support COCOM Requests for Forces, “more often than not, in deference to the COCOMs, the Secretary (of Defense) will direct a service be ‘forced to source’ the requirement.” This particularly strains naval forces, but despite meeting less than 75 percent of regional requests, the U.S. Navy’s ship numbers continue in abject decline since 1986.

But far from inviting service silence, Goldwater Nichols’ final blow against the mechanisms of formal service control emphasized the need for strong advocacy and leadership willing to more aggressively invest a service’s political capital for their needs. For example, Commandant Berger’s necessary shift of Marine Corps’ priorities to Indo-Pacific Command may not please European Command, Central Command, or the retired Marine Corps generals attacking the changes, but the effort is strongly argued, clearly communicated, and involves a candid public discussion of advantages and drawbacks. Although Commandant Berger committed not to ask Congress for “one penny more,” he offered that the Marine Corps “will become smaller if we have to” to support procuring the Light Amphibious Warship (LAW). Such comments demonstrate an organization clear on what costs are acceptable to pursue priorities and a willingness to discuss the logic publicly – demonstrating a level of candor to which extra resources may be entrusted.

Avoiding Self-Delusion and Self-Destruction

The results of these acts continue to solidify disaster for U.S. military efficacy, from the operational and strategic failures of Afghanistan, to the systemic under-resourcing leading to the 2017 collisions, to the 20-year relative shift in strength between the U.S. Navy and PLA Navy. This is not a reflection of the people who provide advice but a reflection of the mistaken civil-military norms, legislated and trained to, that see even honest and professional divergence before Congress as a breach. To meet the mistakenly perceived norm and not breach the trust of the executive branch, military officers swallow dissenting advice to avoid the perception of division. Generations of officers in Afghanistan understood reconstruction flagged under endemic corruption and that removal of U.S. support would trigger a collapse. However, leadership sustained executive continuation of policy through echoes of advocacy, hoping solutions would appear or institutional inertia might change without leaders showing disobedience by touching the scale alone.

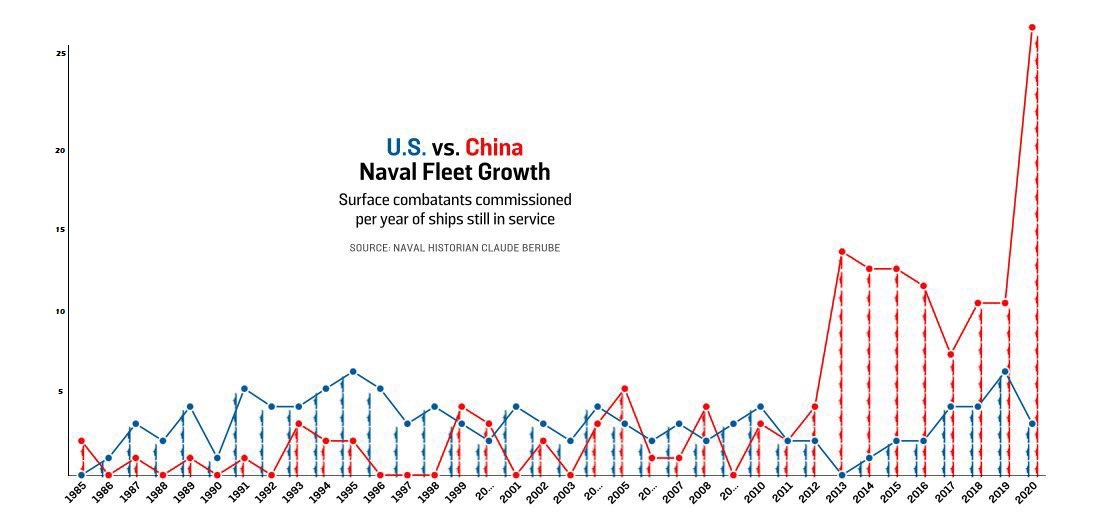

Unlike the chronic ills of Afghanistan, the threats faced by the Navy are acute. The PLAN surpassed the U.S. Navy in size and operates with strength in its home waters while supported by a robust detection and area denial network. Furthermore, the PRC operates a world-class maritime industrial base capable of greater peacetime production and wartime repair than what the U.S. domestic market can achieve. Yet when offered the chance to advocate for more resources by Congress, leadership declines. The CNO’s recent call for a 500-ship navy is a start, but its aspirational 18-year timeline without a shipbuilding plan fails to provide the strong budgetary request or inter-service knife-fight needed today to reach for these goals tomorrow, or clarify the fleet capacity questions of the near future. Further, with a requirement to build net 12.5 ships every year to meet the aspirational 500 goal by 2040 or roughly net 8 ships per year to reach the 355-ship legal requirement by at least 2030 – the Navy clearly declines to fight for its legal and operational needs.

Continued deference to OSD’s managed veneer of agreement over hard-nosed budgetary fights and reform will put the U.S. Navy in a tactical and strategic position with many parallels to the Russian Army’s present disaster in Ukraine. After a contentious period of reforms focused on procurement, financial discipline, and professionalization under Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, since 2012 Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu smoothed ruffled feathers by prioritizing palace politics and avoiding interagency conflict. Difficult choices were avoided, the right stories were told, and the right contracts were sold. With political tradeoffs made, Russia now fights with a vast military capacity gutted of capability, bereft of morale, riven with corruption, and led by generations of weak, unprofessional NCO’s — all problems it claims to have solved over the last decade.

The U.S. Navy faces roughly the reverse – a shrinking, well armed force with strong NCOs whose more principled service leadership eschews conflict with OSD and other services by over-selling capability as a cure for the increasing gap in capacity. Minister Shoigu bought smooth politics and the veneer of capability by selling his military out to the right political partners; the U.S. Navy invests in the veneer of inter-service agreement by over-selling the capacity of a small, capable force and avoiding institutional confrontation. In both cases, the forces are supported by supply chains insufficient in both resiliency and capacity. Whether Russia’s corruption or America’s strategically questionable deference to OSD over congressional oversight, disillusioning defeat is the common result of sacrificing necessary debates on the altar of organizational politics.

The U.S. is out of space, money, and time for the Navy’s multi-generational plans that avoid uncomfortable disagreements while awaiting tectonically slow shifts in OSD bureaucratic and strategic inertia. In a decade where China seeks ascendance with a likely vassal Russia in tow, the U.S. and its public needs a strong, forward, and mobile military to backstop American interests abroad. The military’s failure to understand its rightful place in answering both to the executive and legislative branches has impoverished the public debate on military and foreign policy matters, and weakened national security. Strong, innovative leadership comfortable with serious but professional public disagreements between OSD and other services is necessary to innovate and advocate for America’s pressing security needs. Such leadership is possible, as proven by Admiral Burke, General Shinseki, General Berger, Vice Admiral Copeman, and others who took the right risks for the right reasons. If Washington headquarters continue to fear dissenting conversations held in public more than war, our Navy – and military generally – will face brutal defeat and the ascendancy of a system determined by strategic adversaries.

Matthew Hipple is an active duty naval officer and former President of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC).

CDR Mike DeBoer is a naval officer.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of any U.S. government department or agency.

Featured Image: Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., left, greets Vice Adm. Michael Gilday, right, at Gilday’s confirmation hearing to be the next chief of naval operations on July 31, 2019. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

Very good article. The roll up of legislative acts supportive of the National Security Act of 1947 were invaluable. Service Chief’s owe an honest assessment to Congress. Its not just pleading your case for resources–but telling Congress how we can win the next fight.

Excellent post which explains what we are observing. I’d like to see the counter-argument, to fully appreciate the extent of the issue. But VADM Copeman’s 2013 statement, “I’d give up force structure to get wholeness,” makes it clear that OSD chose the opposite. As the authors say, “the U.S. Navy’s ship numbers continue in abject decline since 1986.” So, we might conclude that choosing force structure when OSD controls the shape of Navy’s budget, will result in declining wholeness and force structure.

But, in addition to identifying the adverse influence of OSD and joint harmony, understanding Navy’s execution shortfalls should be undertaken and where appropriate clearly linked to this problem. That requires some introspection about where and how things go wrong in acquisition programs and in the constituent pillars of wholeness. We need ensure that we’ve done everything possible within our control as we seek relief from this issue. I believe the result will be a stronger argument for change.

Tremendous work, Sirs. Thank you.

Excellent writing.

For consideration:

The Navy, at large, low balls joint education and participation in Joint Assignments. 22.5 months and done. A majority of our senior war college attendees (NDU-North Campus, excluded) are passed over O-5s with little hope for follow on career mobility. Rarely do we send our best to these colleges.

We are at a disadvantage with the Air Force, Army, and Marine Corps when we get in these budgetary knife fights. A typical colonel has been to at least two war colleges and likely has held multiple joint assignments by the time they hit 23 yrs. It is competitive and considered honorable to SELECT for a war college.

We cannot continue to ignore joint doctrine and assignments with the arrogance that we are smarter and can just figure it out. We are showing up to the fight with a butter knife. Continuing to not learn the rules of the game and assuming we’ll figure it out is a dangerous mentality in preparing for war and acquisition.

We have an opportunity to make changes in the Navy. With the change from High-3 to BRS, we need to examine how our career paths are written and make changes. GNA isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Note: COCOM is an authority. You meant CCDR or Combatant Commander. Source: JP 1-0, II-11.

Appreciate catching the JP 1-0 authority vs. position. Unfortunately the errant substitution has almost worked through the halllway lexicon and incites cries of pedantry instead of humble acknowledgment of doctrinal truth.

I also maintain the issue of meeting COCOM (sic) demands at the expense of the services is usually held by similarly doctrinal neophytes who fall short in recognizing the real issue is a matter of risk transference. A CCDR maintains risk if s/he accepts the sourced forces. Elevating the force requirement and capability gap to the Joint Staff and the Secretary correctly moves risk to the higher echelon. It is not the CCDR who is to blame for articulating requirements, nor the Service Chief for attempting to hold back the floodgates of force provision. It is the adjudicated risk that comes from the Chairman to the Secretary of Defense orders that holds the final accountability and responsibility.

I think the authors made a grave error here in this statement: “Since 1974, the only doctrinal innovation conceived and planned by a service and funded by Congress was AirLand Battle.” The 1980’s Maritime Strategy and attendant 600 ship Navy were an innovative doctrinal and operational concept and it was fully funded through 1988 (from 1982.) That’s pretty good for govt standards and the navy deserves great credit for that effort. The link between acquisition issues and Goldwater Nichols is the excellent RAND document: Goldwater Nichols, The Perfect Storm. https://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP308.html?msclkid=4af600c2bf2611ec8a262958bbd95f0b