By Bakhtiyar Askaruly

Kazakhstan is the largest landlocked country, relying heavily on a resource-exporting economy, with the main route to international markets going through Russian territory.1 For many years, Kazakhstan did not experience any interruptions while exporting its resources, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine now challenges Kazakhstan’s economic and security stability. Russia has blocked Kazakhstan’s oil exports by shutting down a pumping station in the Black Sea port to draw Kazakhstan into its advantageous political stance vis-à-vis Ukraine. Kazakhstan is now exploring different routes for its resource exports. The Caspian Sea offers a promising option but will require sea lines of communication (SLOC). Kazakhstan should build a “Fleet in being” to protect its lines of communication, guaranteeing access to the Caspian Sea.2

80 percent of Kazakhstan’s GDP comes from oil and gas exports.3 90 percent of those oil exports go to European markets through Russian territory via pipelines.4 Kazakhstan’s reliance on energy exports places the country in a vulnerable position that is now being exploited by Russia. In 2022, Russia shut down oil transportation several times in response to Kazakhstan’s chosen foreign policy. On March 20, 2022, high seas in the Black Sea allegedly damaged the oil pumping station, but under nefarious circumstances. During the two-week disruption, Kazakhstan lost up to 300 million dollars in revenues.5 Before this event, reports surfaced that Kazakhstan chose not to send troops to Ukraine to fight alongside Russian forces.6 On June 20, 2022, Russia shut off its oil pumping station in the Black Sea a second time due to discovered malfunctions. The second disruption coincided with Kazakhstan’s Presidential announcement of non-recognition of Russian-occupied Ukraine territories on June 17, 2022.7 The third interruption occurred on July 6 when a Russian local court halted exports under the guise of an oil spill.8

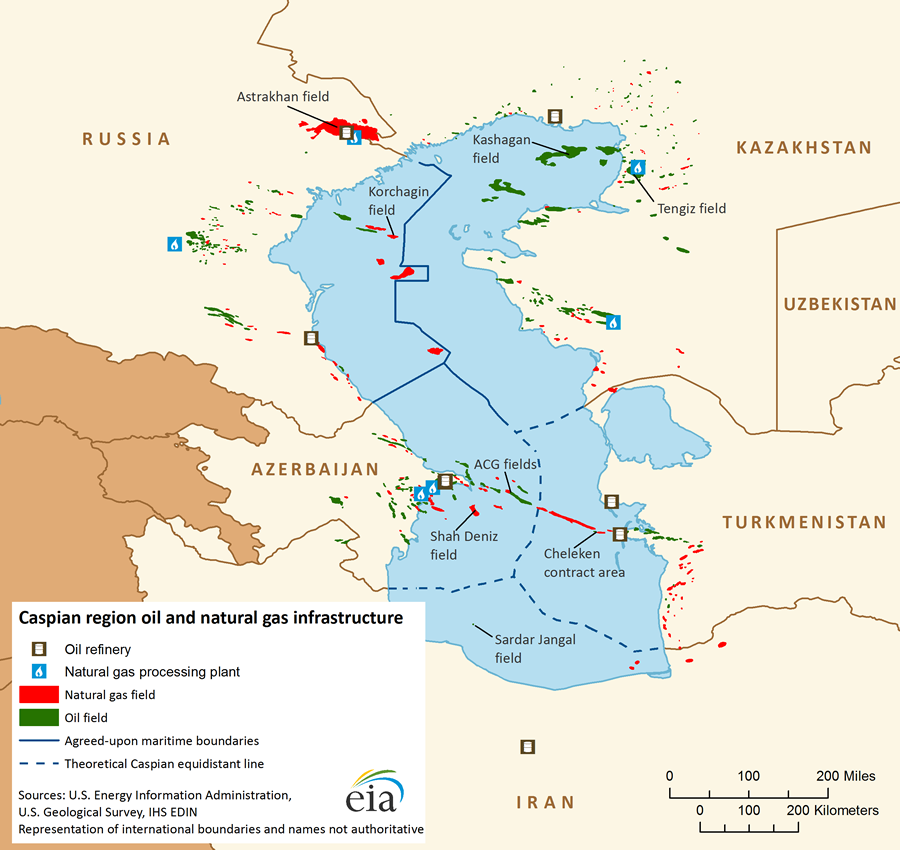

In response to the oil export interruption, on July 7 Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev urged the development of alternative routes for oil export. He directed a study to examine the construction of an underwater pipeline and the use of an oil tanker fleet in the Caspian Sea.9 Similar proposals for an underwater pipeline took place in the 1990s but remained blueprints and mockups. In the 1990’s U.S. companies undertook the Transcaspian gas pipeline project, which was aimed to transport gas from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and later from Kazakhstan to European markets. The Clinton administration created a new position in the State Department for Caspian gas and oil projects. In turn, Russia appointed two high-level government representatives to address the Caspian issues. Moscow also agreed with Iran for strategic energy cooperation in the region, meant to block any efforts for a trans-Caspian pipeline not under Russia’s control or influence.10 Both countries used the unresolved status of the Caspian Sea to impede any further development of energy transfer options.

In 2018, the Caspian Convention regional countries signed a pact to exclude Russian and Iranian vetoes over a trans-Caspian gas pipeline.11 This new legal status for the Caspian Sea allows Kazakhstan to diversify its oil export transit options. This project’s completion remains uncertain due to Russia’s opposition. Another option for Kazakhstan is to build a tanker fleet and expand port capabilities. In the future, a Caspian oil tanker fleet could move up to 30 percent of oil exports through the Caspian Sea.12 However, oil tankers in the Caspian remain vulnerable to adversaries’ provocations without appropriate protection offered by the Corbettian concept of a “Fleet in Being,” providing security to a friendly fleet, and defending against unwarranted attacks.

The military balance of power in the Caspian Sea is shared between five countries: Russia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan. Russia holds “local command” of the Caspian Sea with its relatively significant fleet for this isolated body of water. The Russian Caspian flotilla consists of 28 warships, including two guided missile frigates, eight corvettes, four patrol boats, seven minesweepers, six landing craft, and a gunboat.13 Iran’s fleet comprises one frigate, two corvettes, and ten patrol boats. Azerbaijan possesses one frigate, four submarines, and dozens of patrol boats. Kazakhstan’s fleet comprises two missile boats, two patrol boats, and one minesweeper. Turkmenistan’s fleet is even smaller.

Kazakhstan’s present naval fleet remains inferior compared to the top threat. Russian and Iranian cooperation further compromises Kazakhstan’s already precarious position. Kazakhstan’s fleet only patrols the littorals and provides security for offshore oil extraction.

In the face of new challenges, namely developing new export routes through the Caspian Sea, Kazakhstan should build a “Fleet in Being” to ensure the denial of adversaries. The main task of Kazakhstan’s fleet should be focused on quick reaction to any provocation on its SLOCs, which are approximately 300 kilometers in length. This could be resolved by three to five corvettes and dozens of smaller high-speed boats with effective firepower, such as anti-ship cruise missiles. More significantly however, a naval buildup might stimulate further militarization and an arms race in the Caspian Sea. To mitigate these risks surface ships numbers should be enough to present a credible threat, but appear defensive.

To ensure that any adversary’s action in the sea would be defeated, Kazakhstan might acquire ISR systems and loitering munitions. This capability combination proved effective in the second Nagorno-Karabakh War.14 ISR systems such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) would be able to provide locations of ships and targeting information, while loitering munitions could deliver precision strikes, similar to current operations in Ukraine. The main requirements for such platforms can include UAVs that are able to operate beyond an adversary’s effective range while being able to relay the target’s location. Loitering munitions should feature enough explosives to cripple a corvette-sized vessel. For instance, the Harop drone could be used as a loitering munition designed to locate and strike with 23 kg of high explosive. It also can be safely landed and relaunched.15

The combination of UAVs and loitering munitions can avoid an unnecessary arms race in the Caspian Sea. It is also cheaper to acquire and maintain them. Another advantage of this combination is that they can be used in other tasks in different locations. Loitering munitions can be operated in low altitudes above the sea surface, making them highly survivable. They can an effective range of 1,000 km and 9 hours of flight endurance.16 Units that operate this system could train in any location in the vast steppe of Kazakhstan. In concert with the abovementioned ship capabilities, they can also provide a credible deterrent.

Conclusion

In the face of geopolitical challenges, Kazakhstan is positioned to diversify its oil exports through the Caspian Sea. However, the country’s naval power might not be able to provide secure lines of communication since it was designed to patrol seashore and offshore oil production, more like the functions of a coast guard. To ensure SLOC security, Kazakhstan should build a “Fleet in being.” That capability could consist of additional corvettes armed with cruise missiles, as well as ISR systems and loitering munitions. This combination promises to be an effective deterrent while not provoking an arms race in the Caspian Sea.

Bakhtiyar Askaruly is a pseudonym for a military officer of a Central Asian nation.

References

1. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/kazakhstan-transport-and-logistics (accessed 4-30-2023)/

2. Sir Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press Reprint, 1988), 165. This passage describes what is meant by this term, a force than can “dispute” command of the sea.

3. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/kaz#:~:text=Yearly%20Trade,-%23permalink%20to%20section&text=The%20most%20recent%20exports%20are,and%20Germany%20(%243.82B) (accessed 4-30-2023)…

4. https://russianstudiesromania.eu/2022/07/23/russia-could-stop-the-transit-of-kazakh-oil-to-europe/ (accessed 4-30-2023).

5. https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/uscherb-ot-avarii-na-ktk-nazval-ministr-finansov-466764/ (accessed 4-30-2023).

6. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/live-blog/russia-ukraine-live-updates-n1289976/ncrd1289985#liveBlogCards (accessed 4-30-2023.

7. https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-russia-frictions-over-ukraine-war-go-public (accessed 4-30-2023).

8. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/russian-court-suspends-oil-flows-through-caspian-pipeline-2022-07-06/ (accessed 4-30-2023).

9. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/kazakhstan-needs-diversify-oil-supply-routes-tokayev-says-2022-07-07/ (accessed 4-30-2023).

10. Fiona Hill, “Pipelines in the Caspian: Catalyst or Cure-all?” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (Winter/Spring 2004): 17.

11. Robert M. Cutler, The Trans-Caspian Is a Pipeline for a Geopolitical Commission, Energy Security Program Policy Paper No. 1 (March 2020: NATO association of Canada).

12. https://astanatimes.com/2023/03/kazakhstan-on-its-way-to-oil-supply-diversification/ (accessed 4-30-2023).

13. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/august/caspian-flotilla-russias-offensive-reinvention

14. John Antal, 7 Seconds to Die, (Oxford, UK: Casemate Publisher, 2022).

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

Featured Image: A Russian Navy Caspian Flotilla warship fires a Kalibr-NK cruise missile during naval drills. (Photo via Russian Ministry of Defense)

Supporting the development of this fleet in being would be a cheap and god U.S. policy move.

First, let the Turks do it for us if they want to make the same play. Kazakhstan’s only major shipyard needs investment and is for sale so as to obtain the needed upgrades. The U.S. can’t be that player. Turkey could and looks poised to do so. They also have given Turkmenistan a credible, modern 33m fast attack craft.

Another great option here would be setting them up to assemble boats by kit similar to the Swiftships arrangement with the Egyptian Navy on the 28m patrol boats. They are also negotiating to do the same with the 35m Aluminum patrol boats Swiftships recently delivered to Bahrain. We could structure this as a Muslim country helping a Muslim country. These are good options as the Kazaks are already familiar with MTU 2000/4000 engines in their existing fleet. The boats would need some changes so they are more attack craft than patrol boats for an A2/AD. Leave the RIBs ashore and mount 2 Harpoon to start. Probably integrate a UAV to hunt for targets. Try to keep it simple until we know we can trust the Kazaks to not hand advanced gear over to the Russians. I suggest the kit model as I suspect much of this material will need flown in as Russia would restrict its movement via the Volga canal?