By Christopher Nelson

I recently had the chance to correspond with Dr. Kathleen Williams about her new book, Painting War: George Plante’s Combat Art in World War II. I am personally fascinated with the intersection of art and war, and works that explore the lives of artists that were not behind a gun but who observed and captured war with their art are certainly worthwhile.

Nelson: Kathy, thanks for joining me to discuss your new book. To begin, who was George Plante? Give us a brief biographical sketch of this man, the center of your book.

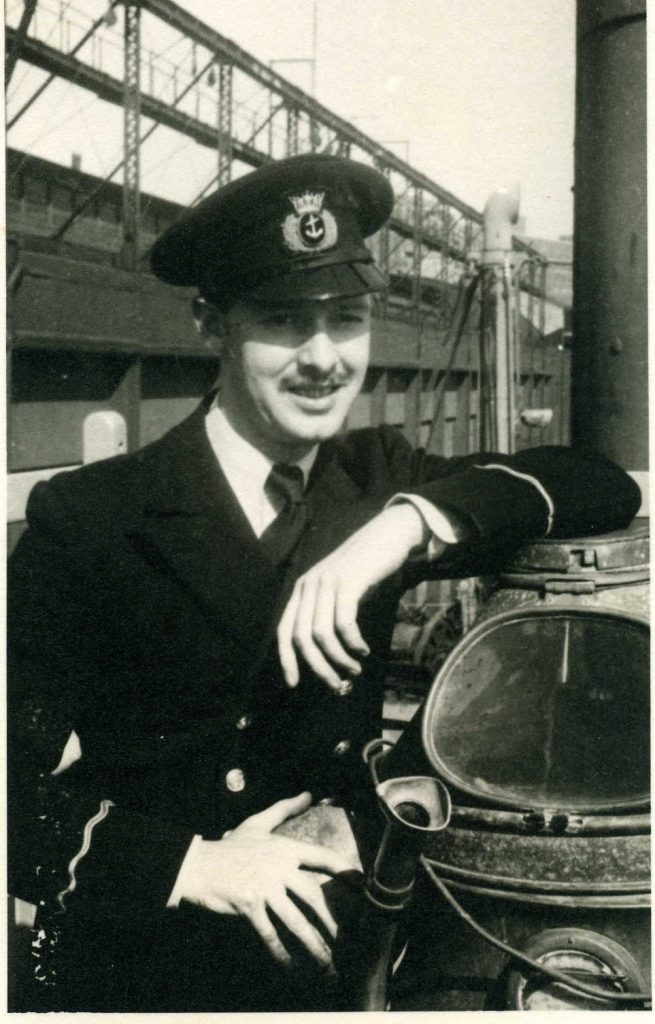

Williams: George Plante, a Scot, was born in Edinburgh in 1914. He trained as an artist at the Edinburgh College of Art and the Contempora School of Applied Arts in Berlin. On the outbreak of WWII he was working for an advertising agency in London when he took radio officer’s training and spent the next several years in the British Merchant Navy traversing the North Atlantic on oil tankers. On his many stops in New York, he cultivated American advertising contacts and developed a profound affinity for the country and its people.

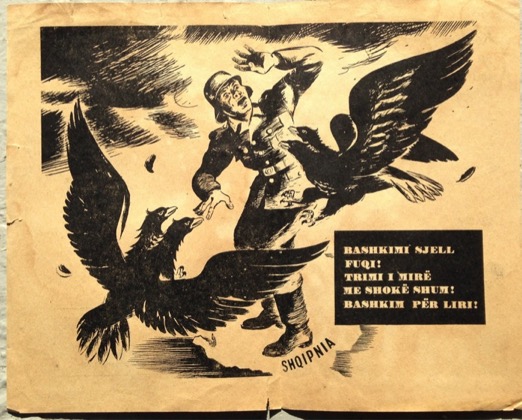

He also secured the support of the War Artist’s Advisory Committee and was assigned to spend much of his time at sea painting the Battle of the Atlantic. His paintings were widely exhibited in the U.S. and became a part of the British campaign to encourage American support for the war against the Nazis. On shore leave in London after his tanker was torpedoed under him in March 1943, Plante was recruited to work for the clandestine Political Warfare Executive. He was sent to Cairo and spent the rest of the war there and in Italy producing illustrations for propaganda leaflets that were dropped over Nazi-occupied southern and eastern Europe. This propaganda effort was a joint Allied endeavor and once again Plante worked closely with American colleagues.

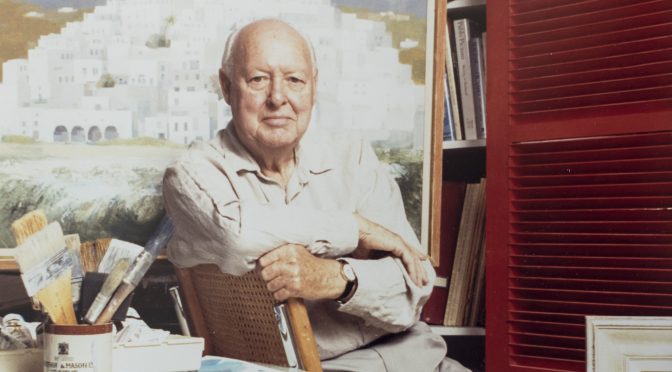

After the end of the war Plante spent the rest of his working life carving out a very successful career in advertising, for many years with the London branch of an American agency and finally with a British company. He also continued to paint for his own pleasure and had numbers of well-received shows. In the 1950s he married an American and on his retirement they moved to the States were he lived until his death in 1995, not long after becoming a U.S. citizen

Nelson: As you mentioned, he spent a deployment on a merchant vessel, operating in waters off the Gulf Coast and the East Coast of the United States. As you write in your book, U-boats were a concern for all in those waters during the early war years. Yet he was drawing and making art while working as a radio operator. How did he do this? That is, the sea changes every minute, every hour, how does an artist capture that scene – and doing so during the war?

Williams: Plante had a lifelong habit of making quick sketches of whatever he saw. He also developed his own detailed vocabulary for rapidly recording color, tone and fleeting impressions, so that when he had a chance to paint he had prompts to remind him exactly how the action had looked. Of course, it also took a fierce concentration to be able to paint on a pitching, tossing deck with the constant threat of U-boat attacks. He was greatly helped in his artistic endeavors by being relieved of many of his radio watch duties because his work in support of the British war effort was seen as extremely important.

Nelson: In your acknowledgments, you thank George Plante’s son, Derek, for providing you with many of George’s letters and copies of his sketches. How important were these for you when writing the book?

Williams: Plante’s letters to his Scottish wife provide the backbone of the first part of the book. Without those letters the official account of his tours at sea, his correspondence with the War Artist’s Advisory Committee, and several newspaper articles based on interviews with him would have made for a much less interesting and informative account of his work as an artist in wartime. His letters from Cairo were equally important in providing insight into the activities of an artist engaged in an Anglo-American propaganda effort against the Axis. Plante was an evocative and entertaining writer and continued to write amusing articles and letters for the rest of his life. His sketches provide the visual evidence of his immediate connection to the war and vividly illustrate what he saw and experienced.

Nelson: Was there a particular letter you found touching or that moved you more than others?

Williams: Yes, many, especially the ones from spring/summer 1943 to his wife, Evelyn, when he knew she was pregnant and he wrote “My dearest Evelyn, and Oscar or Judy.” He also wrote a charming letter from Cairo in September 1943 when his son turned one year old. He bought Derek a pair of shoes in the Mousky (the open air market) writing that “they probably won’t fit and might make him have turned-up- toes if they did. But they amused me and I think they’ll make you laugh too.” He also referred to his son as “Little Chief One-Year-Old.”

Nelson: Did he sketch in his letters?

Williams: No, none of his letters have sketches – perhaps they would not have passed the censors?

Nelson: I recall in your introduction that George Plante didn’t enjoy his wartime painting style. Why didn’t he?

Williams: In later years he disliked his wartime painting style, which he found heavy and dark and he often noted that he was glad so many of his paintings had disappeared into the Soviet Union when sent there with an exhibition after the war. Of course the dark realism of his wartime art reflected not only the style of the time but the dark subject matter.

Nelson: If not his war painting style, what style was his favorite?

Williams: He much preferred the soft colors and bright play of light in his later paintings. He particularly enjoyed painting scenery, often including old buildings, and any people were usually small and more or less incidental to the composition as a whole.

Nelson: Some of his sketches, particularly the one of a survivor on the New Zealand ship Takoa, are done with confidence – few strokes, clean lines, and the talent of a graphic illustrator. The sketch of the sailor on the Takoa reminds me of Ronald Searle’s work. Here I’m thinking about Searle’s work during his captivity in Singapore. To that point, did he work with other artists for his propaganda pieces? And did he ever comment about other contemporary artists that were working during the war that he admired?

Williams: Well, he was quite picky about the work of other artists and fairly critical. He did go to as many art shows as he could, especially in Edinburgh and London, and he did admire the work of Erik Ravilious, John Nash, and Edward Ardizzone. In Cairo he worked closely with American artist John Pike whose illustrations he found “certainly very good, sound stuff” although when he arrived in Egypt he pronounced that the work being done was generally of a “dreadfully low” standard. He also thought the work of most Americans was not nearly as efficient as that produced by the British.

Nelson: Tell us about some of the propaganda art operations he did during the war. Here I’m thinking about the one you describe focused on the Allied operations during the Italian campaign.

Williams: On his arrival in Cairo in the summer of 1943 Plante immediately began work on the propaganda campaign designed to break down Italian opposition to the Allies. Among other endeavors he illustrated a small booklet designed to emphasize the deep cultural differences between the Germans and the Italians. He was also deeply involved in illustrating pamphlets, leaflets, and news sheets aimed at the campaigns in Greece, Crete, and the Italian-controlled Dodecanese, in Yugoslavia and in Albania. Nearing the end of the war he also worked on propaganda leaflets aimed at Norway and finally, also at Allied occupied Germany.

Nelson: He also drew maps. This is something I think many of us take for granted in the days of Google and other online mapping services and easy-to-find vector art of geographic features. What were some of the maps he drew and why did he draw them?

Williams: Late in the war Plante produced some rough sketch maps for leaflets demonstrating to occupied populations (and to German occupation troops) the steady Allied advances, both in the Battle of the Atlantic and on the European mainland.

Nelson: As an artist, what was his preferred medium? I see a large mix in the pictures in the book – ink, gouache, and oils. Was he comfortable across all mediums?

Williams: Yes, he was comfortable in all mediums. To the end of his life he seldom went anywhere without his sketchbook which he filled with drawings in pencil. He

produced more finished sketches in ink and also painted scenes in watercolor from his travels all over the world. After the war he seldom painted in gouache and most of his later work was either in watercolor or in oils. His more substantial work was almost always in oil although he produced many smaller very evocative pieces in watercolor.

Nelson: To close, what are some of your favorite drawings that he did? Why do you enjoy them?

Williams: From the wartime I love his painting of his tanker, Southern Princess, burning after being torpedoed. Otherwise I find his postwar art much more appealing, especially some of his paintings of old churches in Greece and on the French Riviera, and a wonderful series of watercolors he was commissioned to paint of Bahrain.

Nelson: Kathy, thanks so much for taking the time to discuss your new book. All the best to you.

Dr. Kathleen Broome Williams holds a BA from Wellesley College, an MA from Columbia University and a PhD in military history from the City University of New York. She has taught at Sophia University in Tokyo; at Florida State University in Panama; at Bronx Community College, City University of New York and also served as Deputy Executive Officer, of the CUNY Graduate Center’s Ph.D. Program in History; at Cogswell Polytechnical College in California; and since retirement she has taught part time at Holy Names University in Oakland. She spent the 2018-19 academic year at the US Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland as the Class of 1957 Distinguished Chair in Naval Heritage. Her published work includes Secret Weapon: U.S. High-frequency Direction Finding in the Battle of the Atlantic (Naval Institute Press, 1996), Improbable Warriors: Women Scientists and the U.S. Navy in World War II, (Naval Institute Press, 2001) John Lyman award for best book in U.S. Naval History, NASOH, 2001; Grace Hopper: Admiral of the Cyber Sea (Naval Institute Press, 2004), John Lyman award for best biography/autobiography in U.S. Naval History, NASOH, 2004; and The Measure of a Man: My Father, the Marine Corps, and Saipan, (Naval Institute Press, 2013) as well as articles and book chapters on naval science and technology. Her new book, Painting War, also published by the Naval Institute Press, was released in May 2019. Formerly executive director of the New York Military Affairs Symposium, trustee of the Societyfor Military History, and regional coordinator for the SMH, she served on the Nominations Committee of NASOH and is now a member of the editorial advisory board of The Journal of Military History, the U.S. Naval Institute’s naval history advisory board, and Marine Corps History magazine’s editorial review board. Although born in the United States, Professor Williams was raised in Italy and England, and later spent many years in Germany, Puerto Rico, Japan, and Panama.

Christopher Nelson is an intelligence officer stationed at the Office of Naval Intelligence in Suitland, Maryland. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. He is a regular contributor to the Center for International Maritime Security. The views here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Navy or the Department of Defense.

Featured Image: Photo of George Plante from cover of Beaufort and South Carolina Low Country Magazine (George Plante papers).